14.5 Scaling that Racial Mountain

W. E. B. Du Bois called for America to honor elite cultural achievements by African American artists. But what did “elite” mean? In what voice, for example, should a Black poet write?

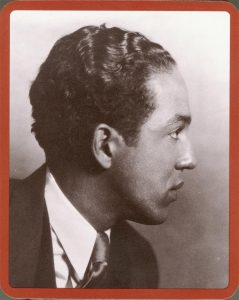

Langston Hughes

|

| James L. Allen. (1930). Portrait of Langston Hughes. |

Perhaps the greatest poet to emerge out of the Harlem community was Langston Hughes. Hughes composed many of his lyrics, including “Mother to Son” (Module 2), in elegant free verse influenced by the Bible and Walt Whitman.

Langston Hughes (1926). “The Negro Speaks of Rivers.”

I’ve known rivers:

I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young.

I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep.

I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it.

I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln went down to New Orleans, and I’ve seen its muddy bosom turn all golden in the sunset.

I’ve known rivers:

Ancient, dusky rivers.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

Hughes’ meditation bonds with ancient ancestral and cultural roots through the metaphor of the river. As a deracinated Black man cut off from his cultural roots by slavery and oppression, he finds links with the peoples of the Nile and the Congo. Between the banks of the Mississippi runs the more recent, blood-soaked history of slaves and the vicious Civil War that freed them but left them enslaved again by an oppressive nation. The meditation transcends the particular and fuses with the human blood of the ages, lit by golden sunset. You have the tools to process the figures of speech: Metaphor, Anaphora, Parallelism, Catalogue.

Langston Hughes could certainly write elegant verse. But he was dissatisfied by the cultural vision, so common among Harlem Renaissance artists, that obsessively scrubbed any trace of the actual voice of his people out of its public image because it supported the stereotype of an inferior race. In 1925, Hughes expressed his frustration at the dilemma facing Black artists in an essay entitled “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain”:

Like Cullen, Hughes was capable of writing verse in any voice. Unlike Cullen, he often chose the voice that rolled richly through Harlem streets and juke joints. Hughes was proud of his people’s music and voice. He entitled his first collection of poetry The Weary Blues (1926) and proved that its rhythms could lead to superb poetry. In Module 2, we explored the structure of a blues: three repetitive lines followed by a resolving line. As you can see and hear, Hughes emulated that blues pattern here.

Langston Hughes (1926). “The Weary Blues.”

Droning a drowsy syncopated tune,

Rocking back and forth to a mellow croon,

I heard a Negro play.

Down on Lenox Avenue the other night

By the pale dull pallor of an old gas light

He did a lazy sway. . . .

He did a lazy sway. . . .

To the tune o’ those Weary Blues.

With his ebony hands on each ivory key

He made that poor piano moan with melody.

O Blues!

Swaying to and fro on his rickety stool

He played that sad raggy tune like a musical fool.

Sweet Blues!

Coming from a black man’s soul.

O Blues!

In a deep song voice with a melancholy tone

I heard that Negro sing, that old piano moan—

“Ain’t got nobody in all this world,

Ain’t got nobody but ma self.

I’s gwine to quit ma frownin’

And put ma troubles on the shelf.”

Thump, thump, thump, went his foot on the floor.

He played a few chords then he sang some more—

“I got the Weary Blues

And I can’t be satisfied.

Got the Weary Blues

And can’t be satisfied—

I ain’t happy no mo’

And I wish that I had died.”

And far into the night he crooned that tune.

The stars went out and so did the moon.

The singer stopped playing and went to bed

While the Weary Blues echoed through his head.

He slept like a rock or a man that’s dead.

Reading this poem, we pass back and forth between two voices: that of the cultivated poet and the street voice of a master of sophisticated music. We may be tempted to dismiss the Blues man’s speaking voice as an expressive instrument less cultured than that masterful music. But what if the problem lies, not in the man’s language, but in our faulty ears?

Zora Neal Hurston

Born in 1891, Zora Neal Hurston grew up in the small town of Eatonville, Florida. Though she traveled far, she never really left. As James Joyce wrote in exile of Dublin, Hurston always wrote of Eatonville. Hurston recognized that the legacy of Eatonville was unique.

|

| Portrait of Zora Neal Hurston. (c. 1943). Photograph. |

Eatonville Florida was a wholly African American town. Let me repeat that. No one who lived in Eatonville wasn’t Black. While its residents mostly worked for White employers in the surrounding towns, the residents of the town had achieved an autonomy unheard of in Jim Crow America. They had a mayor, their own shops, and even, as we learn in a memorable scene from Their Eyes Were Watching God, a street light!

On the first page of this great novel—if only we had time to read it!—Hurston captures the liberating moment when servants return home from serving masters and mistresses:

Growing up in Eatonville, Hurston had a firm conviction of the worth of her own people. As a Master’s candidate in anthropology at Barnard College, Columbia University, she studied under Franz Boas, famous for opening portals into the rich interior of cultural groups dismissed as primitive. When it was time for her to choose a cultural group for an ethnography, she asked for permission.

The result of her study of Eatonville was a collection of folklore well worth our time today. Mules and Men (1935) transcribes folktales, sermons, songs, and front porch banter, respecting and authentically reproducing the language of the people. Unfortunately, Mules and Men is no longer available as a public domain text. But we can sample the incandescent wit of the front porch in a scene from Their Eyes were watching God. Eatonville locals gather on the porch of the community store for a Playin’ de dozens session: contested exchanges of wit by master raconteurs dueling with ritual insults and tall tales.

Sometimes Sam Watson and Lige[1] Moss forced a belly laugh … with their eternal arguments. It never ended because there was no end to reach. It was a contest in hyperbole and carried on for no other reason … Lige would come up with a very grave air … and say, “Dis question done ’bout drove me crazy. And Sam, he know so much into things, Ah wants some information on de subject.” …

Sam begins an elaborate show of avoiding the struggle. That draws everybody on the porch into it. “How come you want me tuh tell yuh? You always claim God done met you round de corner and talked His business wid yuh. ‘Tain’t no use in you askin’ me nothin. Ah’m questionizin’ you.” …

By this time, they are the center of the world. “Whut is it dat keeps uh man from gettin’ burnt on uh red-hot stove — caution or nature?”

“Shucks! Ah thought you had somethin’ hard tuh ast me. … Lige, Ah’m goin tuh tell yuh- Ah’m gointuh run dis conversation from uh gnat heel to uh lice- It’s nature dat keeps uh man off of uh red-hot stove-”

“Uuh huuh! Ah knowed you would going tuh crawl up in dat holler![2] But Ah aims tuh smoke yuh right out- ‘Tain’t no nature at all, it’s caution, Sam.”

“’Tain’t no sich uh thing! Nature tells yuh not tuh fool wid no red-hot stove, and you don’t do it neither”

“Listen’ Sam, if it was nature, nobody wouldn’t have tuh look out for babies touchin’ stoves, would they? ‘Cause dey just naturally wouldn’t touch it- But dey sho will- So it’s caution.”

“Naw it ain’t, it’s nature, cause nature makes caution. It’s de strongest thing dat God ever made, now. Fact is it’s de onliest thing God ever made. He made nature and nature made everything else. … Tell me somethin’ you know of dat nature ain’t made. … [You] know mighty much, but [you] ain’t proved it yit. Sam, Ah say it’s caution, not nature dat keeps folks off uh red-hot stove.”

“How is de son gointuh be before his paw? Nature is de first of everything. Ever since self was self, nature been keepin’ folks off of red-hot stoves. … Show me somethin’ dat caution ever made! Look whut nature took and done.” …

The porch was boiling now. … “Look at dat great big ok scoundrel-beast up dere at Hall’s fillin’ station — uh great big old scoundrel. He eats up all de folks outa de house and den eat de house.”[3]

“Aw ’tain’t no sich a varmint nowhere dat kin eat no house! Dat’s uh lie. Ah wuz dere yiste’ddy and Ah ain’t seen nothin’ lak dat. Where is he?”

“Ah didn’t see him but Ah reckon he is in dc back-yard some place. But dey got his picture out front dere. They was nailin’ it up when Ah come pass dere dis evenin’.”

“Well all right now, if he eats up houses how come he don’t eat up de fillin’ station?”

“Dat’s ’cause dey got him tied up so he can’t. Dey got uh great big picture tellin’ how many gallons of dat Sinclair high-compression gas he drink at one time and he’s more’n uh million years old.”

“’Tain’t nothin’ no million years old! … How dey goin’ to tell he’s uh million years old? Nobody wasn’t born dat fur back.”

“By de rings on his tail Ah reckon. Man, dese white folks got ways for tellin’ anything dey wants tuh know.”

“Well, where he been at all dis time, then?”

“Dey caught him over dere in Egypt. Seem lak he used tuh hang round dere and eat up dem Pharaohs’ tombstones. Dey got dat picture of him doin’ it. Nature is high in uh varmint lak dat. Nature and salt. Dat’s whut makes up strong man lak Big John de Conquer He was uh man wid salt in him. He could give uh flavor to anything.”

“Yeah, but he was uh man dat wuz more’n man. Tain’t no mo’ lak him. He wouldn’t dig potatoes and he wouldn’t rake hay. He wouldn’t take a whipping, and he wouldn’t run away.”

“Oh yeah, somebody else could if dey tried hard enough- Me mahself, Ah got salt in me. …

“Lawd, Ah loves to talk about Big John. Less we tell lies on Ole John.”

Do you find this hard to read? Misspelled words and poor grammar, right? Except that Hurston, a trained anthropologist, is transcribing actual speech. And the grammar is perfectly correct according to the syntax of a dialect quite different from standard, edited English. Hurston respectfully treated the tongue of her people as a language, and decades later linguists realized that she was right. African American English has its own rules and patterns; Hurston is striving to get them right.

Hurston knows that playin’ de dozens, the verbal jousting dismissed by mainstream society as “primitive,” pulses with devastating wit and eloquence. In a time before radio or television, talented jesters gather the town to the front porch of listen to the fun. Sam and Lige vie for the biggest laugh as they probe the nature versus nurture debate that scholars today still wrestle with. Their sham debates are studded with witticisms:

- Ah’m gointuh run dis conversation from uh gnat heel to uh lice (head to toe)

- Ah knowed you was going tuh crawl up in dat holler! (i.e. hollow, a small valley)

- He wouldn’t dig potatoes and he wouldn’t rake hay. He wouldn’t take a whipping, and he wouldn’t run away.

“He wouldn’t take a whipping, and he wouldn’t run away”—who is the he? Big John de Conquer, a standard character in many African American folk tales, was a noble slave who embodies the virtues and courage of a subdued people. The very mention of a hero who could rise above oppression interrupts the sham debate: “Lawd, Ah loves to talk about Big John. Less we tell lies on Ole John.”

Cultures evolve myths to help their people navigate their environment. African American myth projected a facsimile world in which, as in reality, servitude is inescapable, but wit provides a refuge in dignity, grace and humor. In Eatonville, everyone was a servant, but on that front porch, story tellers competed in fantasy heroics, trading insults and making grandiose claims. Rivals playin’ de dozens forged a tradition that eventually led to the global triumph of rap and hip hop.

References

Allen, J. L. (1930). Langston Hughes. [Photograph.] https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/94506949/

Hughes, L. (1926). “The Weary Blues.” In The Weary Blues. New York, NY: Alfred Knopf. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/47347/the-weary-blues.

Hughes, L. (1926). The Negro speaks of rivers. In The Weary Blues. New York, NY: Alfred Knopf. Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44428/the-negro-speaks-of-rivers

Hughes, L. (June 23, 1926). The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain [Article]. The Nation. Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69395/the-negro-artist-and-the-racial-mountain

Hurston, Zora Neal. (1935). Mules and Men. New York: Lippincott.

Hurston, Zora Neal. (1937). Their Eyes Were Watching God. New York, NY: I. B. Lippincott, Inc. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/TheirEyesWereWatchingGodFullBookPDF/page/n89.

Miss Zora Neale Hurston, Negro novelist and anthropologist of New York City and Florida [Photograph]. (c 1935). Washington DC: Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004672085/

a trope which denotes a “non-literal” thing, idea, or action to characterize a “real” term. E.g. “All the world's a stage, and all the men and women merely players” (William Shakespeare, As You Like It, 1599).

a figurative scheme that repeats the same word or phrase at the beginning of sentences or clauses: e.g. “I have a dream …” phrase repeated in Dr. Mar-tin Luther King’s speech, (8/28/1963).

a figurative scheme which arranges phrases, clauses or sentences with the same syntactic or thematic forms

a rhetorical figure that rhythmically lists examples of a category to build in-tensity and emphasis. Common in epic poetry and in free verse in the tradition of Walt Whitman

a competitive activity in traditional African American culture in which contestants exchange ritual insults and outlandish tales to earn by their wit and originality the delight and appreciation of the on looking audience. A cultural precursor to modern rap and hip-hop competitions