13.4 Modernist Photography

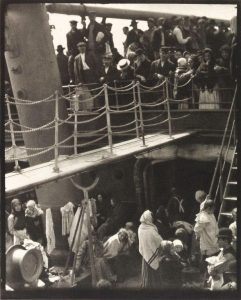

“The scene fascinated me: a round straw hat, the funnel leaning left, the stairway leaning right; the white drawbridge, its railings made of chain; white suspenders crossed on the back of a man below; circular iron machinery; a mast that cut into the sky, completing a triangle. I stood spellbound. I saw shapes related to one another—a picture of shapes, and underlying it, a new vision that held me: simple people; the feeling of ship, ocean, sky. … Rembrandt came into my mind, and I wondered if he would have felt as I did.

—Alfred Stieglitz, quoted in Norman, 1976, p. 9.

Here is Stieglitz’s famous Composition, often cited as the most influential photograph of the Modern era. What do you think?

|

| The Steerage. (1907). |

Stieglitz

In a number of roles, Alfred Stieglitz led photography into maturity as an art form. As a member of the international Linked Ring and New York Camera Club, the increasingly esteemed Stieglitz shared technological innovations and styles with photographers serious about developing the form. As editor and contributor of articles and photographs to American Amateur Photographer and Camera Notes, he committed himself to “my fight—or rather my conscious struggle for the recognition of photography as a new medium of expression, to be respected in its own right, on the same basis as any other art form” (Norman, p. 6).

|

|

|

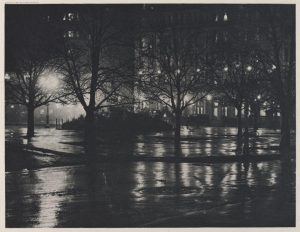

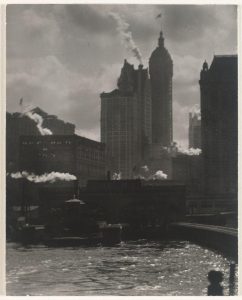

| Reflections: Night, New York (1897). | The City of Ambition (1910). | Stieglitz, A. (1897). Reflections: Night. |

Photographs can be taken for a wide variety of reasons. Stieglitz always sought within moments of vision elements of light, shadow, Line and Form that could be composed for Aesthetic impact. Although color film was being developed, artistic photography embraced the limitation of a black and white palette to produce dramatic contrasts of light and shadow. Roaming New York, Stieglitz found in the sinuous streets and the mass and contours of buildings the building blocks of Geometrical Form.

In 1902, Stieglitz formed Photo-Secession, an organization of artistically minded photographers who wished to pull back from conventional practice. This led to a gallery at 291 Fifth Avenue which displayed not only ambitious photography, but Modern paintings as well. He helped to organize showings of major European artists, helping them find exposure and patronage in the U.S.

Stieglitz’s commitment to the Modern in art can be seen in his choices of subject matter. The modern orientation was inspired by the Geometrical Form that could be seen in technology, industry and contemporary architecture. Contributors to the Photo-Secession movement followed Cezanne in seeking Geometrical Forms that comprised visions, and the clean lines and shapes of technology laid them bare.

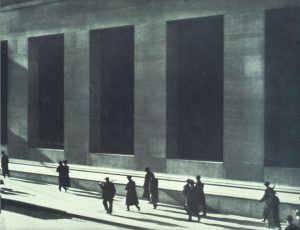

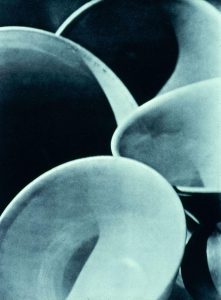

Strand

Paul Strand, an avid photographer, dropped into Stieglitz’s 291 gallery as a teenager. Stieglitz recognized his talent and featured his work in the gallery and his publications. Can you see in these examples of his work the eliciting of Geometric Form out of everyday visions? A street scene. An array of kitchen bowls. Shadows on a porch.

|

|

|

| Pedestrians on Wall Street. (1915). | Abstraction, Bowls. (1915). | Abstraction, Porch Shadows. (1917). |

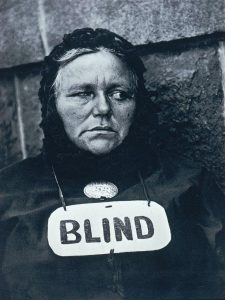

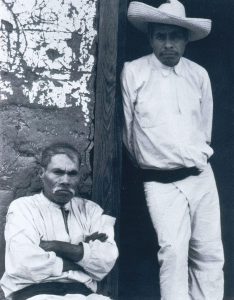

Of course, one of photography’s great powers is realized in Portraits. Like most great photographers, Strand had a knack for capturing the essence of a person in a slit second exposure of film. The portability of the camera enables the photographer to bring the illumination of portraiture to humble, undistinguished people. At its core, photography is a profoundly democratic medium.

|

|

| Blind Woman. (1916). | Men of Santa Ana. (1933). |

Bourke-White

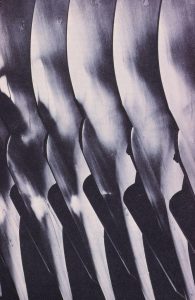

Margaret Bourke-White found a different route to prominence. She opened a studio for photographing, not people, but commercial enterprises. Including architecture and industry. Despite its commercial patronage, Bourke-White’s industrial photography exalted Modern Form over commonplace documentation. Her images of power blades and radio speakers testify more to design than to product virtues.

|

|

|

| Open hearth mill, Ford Motor Co., Detroit. (1925) | Power blades at the Oliver Chilled Plow Co. (1929). | Untitled (RCA Speakers). (1935). |

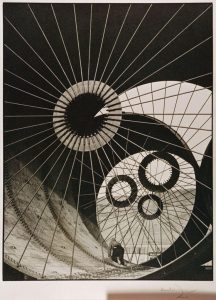

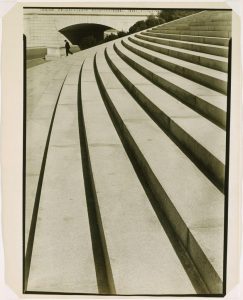

In 1936, the new Life magazine sent Bourke-White to shoot the Fort Peck Dam in Montana. How do you read the Form in these compositions?

|

|

|

| Construction of Fort Peck Dam. (1936). | Fort Peck Dam, Montana. (1936). | Steps, Washington DC. (1934). |

Ansel Adams

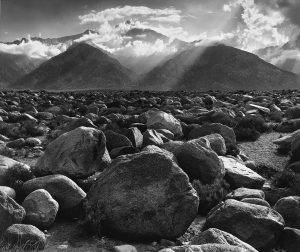

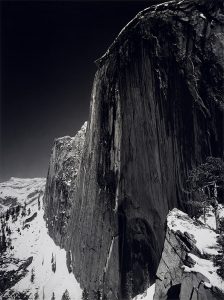

Having grown up in San Francisco, Ansel Adams found the journey to Yosemite National Park a short one. He developed his photographic skills in the National Parks of the West. What principles of composition can you see in these dramatic landscapes? Do you see suggestions of the Sublime?

|

|

|

| Monolith, the Face of Half Dome. (1927). | Half Dome from Glacier Point. (1947) | Yosemite Valley, Thunderstorm. (1949). |

Adams’ contribution to photographic technique was substantial. Advocating for a “pure” photography that uses no manipulation of the image, he helped develop the so-called Zone System for managing shades of light and shadow. Working extensively in large scale landscapes, he used “deep focus” lens settings to accentuate the zones that comprise Depth of Field: foreground, middle distance, deep distance. Compare your experience of these zones in the following compositions.

Adams would often trek all day through the wilds of a National Park carrying a one-shot camera. The discipline required to select and “get” that one shot for the day demands patience and a great eye. And that really is the essence of the art of photography. To be able to see the great shot and then to have the skill to bring the camera’s technologies to bear in capturing it. Many of us like to point our smart phone cameras at the images that crowd our lives. Few of us can forge art out of a fleeting moment.

Vital Questions

Context

The interesting thing about the context for Modern photography is the confluence of Avant-Garde artistic vision and industrial enterprise. For the Modern artist in the first decades of the 20th Century, technology was opening a door to a new and exciting world, encouraging a break with the past and seeming to demand a “new” approach to art.

Content

This fusion of Aesthetic and industrial agendas led to a split focus: on the one hand, the visual subject and on the other hand the component Forms that could be isolated and spotlit in the lens. As a Matisse or a Braque force our eyes to linger on Form, Texture, and Medium, so artists like Strand, Bourke-White, and Adams foreground the formal impact of the composition.

Form

The Modern photographer embraced a compressed range of formal options. Black and white Values that intensified the contrast between light and shadow. Close-ups and Composition that isolated Geometric Form. This was an art form that made a virtue out of limited formal materials.

References

Adams, A. (1947). Half Dome from Glacier Point [Photograph]. The Ansel Adams Gallery https://www.anseladams.com/half-dome-glacier-point/

Adams, A. (April 10, 1927). Monolith, the Face of Half Dome [Photograph]. The Ansel Adams Gallery https://www.anseladams.com/mfhd-about/

Adams, A. (1944). Mount Williamson, the Sierra Nevada, from Manzanar, California [Photograph]. The Ansel Adams Gallery https://articles.anseladams.com/mt-williamson-manzanar/

Adams, A. (1942). Sand Dune, White Sands National Monument, New Mexico [Photograph]. Tempe, AZ: University of Arizona Center for Creative Photography. AN 84.92.102. https://cspace.arts.arizona.edu/detail/dd5b21f1-3e44-46bd-8861

Adams, A. (1942). The Tetons and the Snake River [Photograph]. The Ansel Adams Gallery https://www.anseladams.com/products/explore-tetons-and-the-snake-river

Adams, A. (1949). Yosemite Valley, Thunderstorm [Photograph]. Tempe, AZ: University of Arizona Center for Creative Photography. AN 84.91.240. https://cspace.arts.arizona.edu/detail/55d03e6b-5aa5-4608-b74b

Bourke-White, M. (1936). Fort Peck Dam, Montana [Photograph]. New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art. ON 47.1964 https://www.moma.org/collection/works/44724

Bourke-White, M. (1929). Power blades at the Oliver Chilled Plow Co [Photograph]. Kansas City, MO: Nelson Atkins Museum of Art. https://art.nelson-atkins.org/objects/48924/plow-blades-oliver-chilled-plow-company?ctx=c04ba4af-aed5-4ffe-a724-ba437b1a2cf3&idx=0

Bourke-White, M. (1934). Steps, Washington DC. [Photograph]. The Phillips Collection. AN 1996.002.0001. https://www.phillipscollection.org/collection/steps-washington-dc

Bourke-White, M. (1935). Untitled (RCA Speakers) [Photograph]. San Francisco CA: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. AN 91.374. https://www.sfmoma.org/artwork/91.374/

Bourke-White, M. (1936). Wind Tunnel, Fort Peck Dam [Photograph]. Rochester, NY: Eastman House. https://collections.eastman.org/objects/106395/steel-liner-fort-peck-dam-montana?ctx=7f1c7ac4-6d0b-4add-9f84-57db51a3a2f9&idx=19

Norman, Dorothy. (1976). Alfred Stieglitz. New York: Aperture.

Stieglitz, A. (1910). The City of Ambition [Photograph]. San Francisco CA: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. AN 52. https://www.sfmoma.org/artwork/52.1793/

Stieglitz, A. (1897). Reflections: Night— [Photograph]. Picturesque Bits of New York and Other Studies, San Francisco CA: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. https://www.sfmoma.org/artwork/2013.117.4/

Stieglitz, A. (1907). The Steerage [Photograph]. San Francisco CA: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. https://www.sfmoma.org/artwork/52.1796/

Stieglitz, A. (1931). From my window at the Shelton, North. [Photograph].New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/265144

Strand, P. (1915). Abstraction, Bowls [Photograph]. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/269426

Strand, P. (1917). Abstraction—Porch Shadows [Photograph]. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ON 1987.1100.10 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/265133

Strand, P. (1916). Blind Woman, New York [Photograph]. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ON 33.43.334 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/267748

Strand, P. (1933). Men of Santa Anna, Michoacan [Photograph]. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ON 40.107.5. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/268676

Strand, P. (October 1916). Pedestrians on Wall Street. Camera Work, v. 48, p. 25. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Paul_Strand,_Wall_Street,_New_York_City,_1915.jpg

in visual art, the arrangement of visual elements for expressive and aesthetic impact: unity, proximity, similarity, variety and harmony, emphasis, rhythm, balance, etc

in visual art, a 2-dimensional path through space including length but not width or depth. Line may be straight or curved, directly drawn or implied, e.g. lines of sight, suggested lines of movement, etc.

the elements, patterns, techniques, styles and structures that comprise the composition without regard to subjects, meanings, or values

the dimension of an artistic experience that appeals to or challenges an au-dience’s sense of taste and experience of beauty, ugliness, the sublime, etc. A response distinct from “interested” concerns such as ideology, sexuality, social conflict or economics

a style in the arts associated with the early 20th Century that emphasized formal design and the surface of the medium over any represented or narrated subject

in visual art, a form suggesting human artifice in precise, smooth lines, shapes, and forms such as triangles, rectangles, pyramids or cylinders

in visual art, a composition that represents a human subject as an individual, meticulously capturing physical or psychological likenesses

an aesthetic effect in art in which the viewer or reader experiences awe, even fear in a representation that (safely!) carries the imagination into danger, terror, darkness, solitude, or infinity

in photography, the technique of adjusting the lenses to achieve clear focus on the foreground, the middle distance, the deep distance, or all distances at once (Infinity)

a general term referring to innovative, experimental artistic movements that challenge the conventions of the day

in visual art, the illusion of surface feel either of A) the represented object (e.g. textures of clothing) or B) of the artifact’s media (e.g. canvas weave, brushstrokes, daubs of paint)

the methods and materials from which the work is forged, e.g. oil paint, mosaic, metric verse, prose narrative