10.3 Realism on Canvas

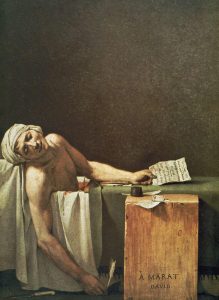

Let’s look at three paintings that deal with human mortality. What do you notice about the difference in their treatment? Which is Neo-Classical? Which is Romantic? How about the third?

|

|

|

| Jacques-Louis David. (1793). Death of Marat. Oil on canvas. | Eugène Delacroix. (1822). The Barque of Dante.[1] Oil on canvas. |

Burial at Ornans. (1850). Oil on canvas. |

[1] Barque of Dante: this is an illustration of a dramatic moment in Dante’s Inferno. Virgil is leading Dante across the river Lethe and into the regions of hell.

In Chapter 9, we learned that Neo-Classical art features clean Lines, strict Linear Perspective, a muted Color Palette, and a sober reflection on duty to the society. Romantic compositions are much more flamboyant, with vivid colors, sweeping, curving lines, and intensely dramatic action. I am sure you can pick out the Neo-Classical and the Romantic compositions. But that third work. In terms of Style, it surely seems more Neo-Classical than Romantic, eh? And yet, thematically, it is quite different.

Gustav Courbet

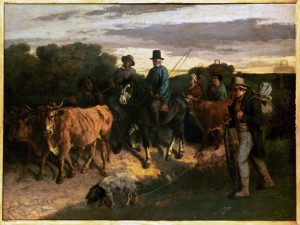

Approached composition with the restraint and elegance of a Neo-Classical painter. But unlike a David, he had no illusions of the glories of the Classical, republican past of ancient Rome or the Neo-Classical imperial glory of Napoleonic France. Courbet’s Burial at Ornans depicts a traditional funeral rite as performed thousands upon thousands of times in the centuries of Roman Catholic Europe. But look closely at the burial party. Faces are turned away in bored disinterest. The faith is represented by vestments and a single, backgrounded crucifix. The people’s somber clothes and dun countryside are lit by no dramatic rays of light promising hope.

|

|

|

| Burial at Ornans. (1850). Oil on canvas. | Peasants of Flagey Returning from the Fair. (1855). Oil on canvas. | The Stone Breakers. (1855). Oil on canvas. |

Courbet challenged the Academic formulas for art which valued portraits of aristocrats and disdained images of common people. He painted, not Napoleon in splendor, but peasants living their daily lives.

Jean-François Millet

Jean- François Millet followed Courbet’s example. His compositions capture the faith and dignity of peasants at their toil. His embrace of the lives of the people is heartfelt and fully committed. The Gleaners, for example, depicts poverty-stricken peasant women who had received permission to “glean” bits of grain left behind by the harvesters.

|

|

|

| The Angelus. (1859). Oil on canvas. | The Haymakers. (1857). Oil on canvas. | The Gleaners. (1857). Oil on canvas. |

Francisco Goya

In Chapter 9, we saw that the Neo-Classical painter Jacques-Louis David supported the French Revolution and, in turn, the empire that Napoleon Buonaparte seized across Europe. You can easily see the propaganda value of his heroic image of Napoleon astride a rearing horse. The composition exudes the gloire which fired the French nation to patriotic fervor.

|

|

| Jacques-Louis David. (1802). Napoleon Crossing Saint Bernhard Pass | Francisco Goya. (1814). Third of May, 1808. Oil on canvas. |

But how did it all seem to the conquered peoples? In 1808, Napoleon invaded Spain, triggering the so-called Peninsular War with Britain. Napoleon’s armies brutally suppressed resistance and dissent. In 1814, Francisco Goya, a favored painter in the Spanish court, offered a very different look at French aggression.

Goya’s composition commemorates the 1808 massacre of Spanish patriots who defended Madrid from French armies. Goya’s work abhors Napoleon’s ruthlessness and celebrates Spain’s liberation. It also anticipates the stylistic challenges that would over the next century break Academic Art’s grip on European painting. His anguished figures are presented with sketchy drawing, flat brushstrokes, and minimal detail.

In Goya’s image, we can see the disillusioned rejection of traditional patriotic idealism that would increasingly drive artists of the mid-19th Century.

Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

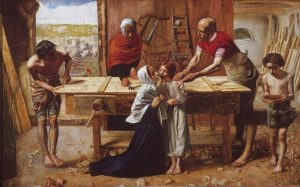

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was a community of painters, many of whom also published poetry, who agreed that art had gone wrong after the time of Raphael. They looked for inspiration in the legendary past and in literature that channeled tradition.

Stylistically, the Pre-Raphaelites are tough to categorize. John Everett Millais envisions a young Jesus working in his father’s carpenter shop, and the treatment is far more realistic than the traditional Biblical image. More frequently, however, the Pre-Raphaelites drenched their precisely modeled compositions in Romantic splashes of color.

|

|

|

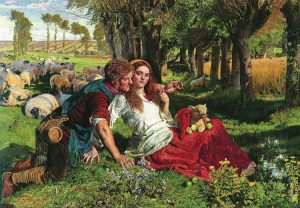

| John Everett. Millais. (1850). Christ in the House of His Parents. Oil on canvas. | William Holman Hunt. (1851). The Hireling Shepherd. Oil on canvas. | Ford Madox Brown. (1855). The Last of England. Oil on canvas. |

Thematically, however, Pre-Raphaelite compositions that are not imaging mythic scenes from England’s past, embraced the lives of common folk with a Realist’s sensitivity. Few roles were lower in English society than that of a shepherd, yet Hunt infuses his swain and his lover with the rich pageantry of an Arthurian knight. The Last of England shares the poignant moment when a young emigrant couple sails away from a country in which thousands could no longer make a life.

Vital Questions

Context

The Realists of 19th Century Europe reflected the disillusionments of a time that repeatedly saw revolutionary hopes devolve into predatory empires, ruinous wars and reform governments that failed to deliver on the hopes they had inspired in people beset by centuries of poverty and oppression. They lacked both the Neo-Classical faith in past glory and the Romantic faith in the glory of dramatic moments of action.

Content

Courbet and his followers made a decisive shift in subject matter that would have long lasting influence. They chose the lives of humble, working people as Visual Subjects fit for serious artistic attention. As we will see, this embrace of non-aristocratic social castes would continue and expand until the notion of painting a working-class person became unworthy of note.

Form

Formally, Courbet and Millet share much in common with the Neo-Classical painters. Their technique is Mimetic and quietly styled. Nothing revolutionary jumps out of it. And yet, as we will see in Module 6, their example would prove the launching point for explosive innovations that would break out in shocking directions. Stay tuned.

References

Brown, F. M. (1855). The Last of England [Painting]. Birmingham, UK: Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ford_Madox_Brown,_The_last_of_England.jpg

Courbet, G. (1850). A Burial at Ornans [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musée d’Orsay. https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/un-enterrement-ornans-924

Courbet, G. (1855). The Peasants of Flagey Returning from the Fair [Painting]. Besançon, FR: Musée des Beaux-Arts et d’archéologie de Besançon. https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/les-paysans-de-flagey-10505

Courbet, G. (1849). The Stone Breakers [Painting]. Work has been destroyed. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/gustave-courbet/the-stone-breakers-1849

Courbet, Gustave. (1855). Les Cribleuses de blé (The Wheat Sifters) [Painting]. Nantes FR: Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/gustave-courbet/the-wheat-sifters-1855-1

David, Jacques Louis. (1793). Death of Marat [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musée du Louvre. RF 1945 2. https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010059773

David, Jacques-Louis. (1801-1802). Napoleon Crossing the Saint Bernhard Pass. [Painting]. Versailles, FR: Chateau de Versaille. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/jacques-louis-david/napoleoncrossing-the-alps-at-the-st-bernard-pass-20th-may-1800-1801

Delacroix, Eugène. (1822). The Barque of Dante [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musée du Louvre. INV 3820; L 3837. https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010065871

Goya, Francisco. (1814). 3rd of May 1808 [Painting]. Madrid, Spain: Museo del Prado. https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/the-3rd-of-may-1808-in-madrid-or-the-executions/5e177409-2993-4240-97fb-847a02c6496c

Hunt, William Holman. (1851). The Hireling Shepherd [Painting]. Manchester, UK: Manchester Art Gallery, Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/william-holman-hunt/the-hireling-shepherd

Millais, J. E. (1850). Christ in the House of His Parents [Painting]. London, UK: Tate, Britain. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/millais-christ-in-the-house-of-his-parents-the-carpenters-shop-n03584

Millet, J-F. (1859). The Angelus [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musée d’Orsay, inv. RF 1877. https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/langelus-345

Millet, Jean-François. (1857). The Gleaners [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musée d’Orsay. https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/des-glaneuses-342

Millet, J-F. (1857). The Haymakers [Painting]. Paris, FR: Musée du Louvre. RF 1439. https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010059359

a style of art that emulates a former classical age, generally emphasizing conventional rules, mathematical precision, and reason over passion

committed to the late 18th and 19th Century reaction against Neo-Classical reason which sought to liberate the individual human imagination and embrace its passions, dreams, and irrational visions as sources of wisdom.

in visual art, a 2-dimensional path through space including length but not width or depth. Line may be straight or curved, directly drawn or implied, e.g. lines of sight, suggested lines of movement, etc.

the illusion of depth in a 2-dimensional image (e.g. a painting) in which contour or architectural lines angle toward a vanishing point

a particular array of colors strategically selected for an individual composition to achieve an emotional, thematic, or aesthetic effect. A term derived from an artist’s decision about the colors to add to a palette for a particular session.

a consistent pattern of choices regarding form and technique that comprise an identity for an artistic tradition, movement, or individual vision

A) an aesthetic valuing clarity, order, balance, unity, symmetry, and dignity, usually honoring a cultural tradition associated with some golden age of the past. B) in the Euro-American tradition, a reference to the works, styles, and themes of Greek and Roman antiquity.

art that follows explicit rules established by a tradition, institution, academy, or school. Sometimes dismissed by the avant-garde art world as overly cautious, derivative, or unoriginal.

A) an artist or writer who cultivated an attitude of disillusionment that probes darker aspects of life which punctures the delusions of conventional assumption. B) member of a 19th Century school of painting that respectfully but soberly depicted the lives of ordinary people in a spare, restrained style that relies on accuracy and detail to indicate unpleasant truths.

in visual art, the elements that comprise the composition irrespective of any subject or signification: line, color, form and shape, value, texture, space, and movement