8.6 The Sonnet–5 Centuries and Counting

Courtly Love Sonnets exploded as a fad in the Elizabethan court. But the form turned out to have a long life. Poets into our own time have found it to be a flexible and powerful form.

Let’s sample just a few pearls from that tradition. Below, you will find four Sonnets from major poets. Your challenge: choose one of the sonnets. Use our process to break it down: sound, senses, theme.

What is the sonnet’s Rhyme Scheme?

What are the boundaries of the Stanzas.

Whose voice is talking? To whom? About what?

What is the Theme of each stanza?

Where is the Thematic Turn in the Sonnet?

Is this a Petrarchan or a Shakespearian Sonnet?

How do you read two or three Tropes in the poem?

John Milton: Faithful Service

John Milton, a giant of English literature, was a premier Classical scholar who wrote the great Christian epic Paradise Lost (1667). He also wrote voluminously in defense of Parliamentary forces during the Englich Civil Wars and Oliver Cromwell’s Puritan government, the Commonwealth. Incessant study and writing eroded his eyesight, and he became totally blind by the age of 44. His reflection on the price he was paying for his life’s work wrestles with personal despair: how can a scholar and writer be asked to persevere in blindness?

John Milton. (c 1652). Sonnet 19

When I consider how my light is spent,

Ere half my days, in this dark world and wide,

And that one Talent[1] which is death to hide

Lodged with me useless, though my Soul more bent

To serve therewith my Maker, and present

My true account, lest he returning chide;[2]

“Doth God exact day-labor,[3] light denied?”[4]

I fondly ask. But patience,[5] to prevent

That murmur, soon replies, “God doth not need

Either man’s work or his own gifts; who best

Bear his mild yoke, they serve him best. His state

Is Kingly. Thousands at his bidding speed

And post[6] o’er Land and Ocean without rest:

They also serve who only stand and wait.”

[1] Talent: a reference to Jesus parable of the talents, Matthew 25:14–30. A talent in Jesus’ day was a large sum of money. In the parable, three servants were given money to invest. The first two earned praise by increasing their funds. The last was condemned for burying the money to keep it safe.

[2] Chide: i.e. reprove, find fault with

[3] Day-labor: i.e. perform daily labor for a wage

[4] Light denied: i.e. blame me for not performing work that requires light when light is not available

[5] Patience: here the quality of patience is personified and engaged in a dialogue with the poem’s voice, counseling perseverance.

[6] Post: i.e. travel by coach, the primary form of travel in the 17th Century.

A Vision of London

As we will see in the next Module, William Wordsworth spent as much of his life as he possibly could in the natural splendors of his regional home, England’s Lake District. Tramping its woods and glens, he found artistic and spiritual inspiration in its plants, animals, and vistas.

Wordsworth’s sonnet of 1802 gains impact when we compare its vision of London’s heart with his woodland orientation. How does this naturalist find inspiration in an impression of a sleeping city?

William Wordsworth. (1802). “Composed upon Westminster Bridge, September 3, 1802”

Earth has not anything to show more fair:[1]

Dull would he be of soul who could pass by

A sight so touching in its majesty:

This City[2] now doth, like a garment, wear

The beauty of the morning; silent, bare,

Ships, towers, domes, theatres, and temples lie

Open unto the fields, and to the sky;

All bright and glittering in the smokeless air.

Never did sun more beautifully steep

In his first splendor, valley, rock, or hill;

Ne’er saw I, never felt, a calm so deep!

The river glideth at his own sweet will:

Dear God! the very houses seem asleep;

And all that mighty heart is lying still!

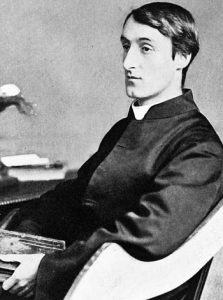

Gerard Manly Hopkins: God’s Elusive Grandeur

|

| Gerard Manley Hopkins. (1918). Photograph. |

Gerard Manley Hopkins, an Anglo-Catholic priest, probed the dynamics of faith in knotty verses that challenged readers rhythmically and thematically. Hopkins knew that faith is hard and, unlike many writers of devotional verse, he forced readers to slow down, think, feel, and win through to a thematic resolution.

Gerard Manley Hopkins. (1877) “God’s Grandeur”

The world is charged with the grandeur of God.

It will flame out, like shining from shook foil;

It gathers to a greatness, like the ooze of oil

Crushed. Why do men then now not reck his rod?[1]

Generations have trod, have trod, have trod;

And all is seared with trade;[2] bleared, smeared with toil;

And wears man’s smudge and shares man’s smell: the soil

Is bare now, nor can foot feel, being shod.

And for all this,[3] nature is never spent;[4]

There lives the dearest freshness deep down things;

And though the last lights off the black West went

Oh, morning, at the brown brink eastward, springs —

Because the Holy Ghost over the bent

World broods[5] with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.

[1] Reck his rod: that is recognize God’s rod of authority

[2] Trade: in Victorian society, trade was the engine of economic growth, but it was nevertheless despised as a sign of social inferiority. The aristocrat and the gentleman or woman had independent means and did not dirty their hands with trade.

[3] For all this: the word for in this case means despite—even though all this is true …

[4] Spent: i.e. depleted, worn out

[5] Broods: i.e. sitting protectively over unhatched eggs, as does a mother hen

The world is charged with the grandeur of God. This is Hopkins’ great theme, one easy to misread. Hopkins never writes of God’s grandeur as a glaring coat of enamel. The word “charged” should be read as elusive potentiality, a compressed, unreleased electrical force. What do you see in the series of Metaphors which flare with sudden eruptions of God’s presence? Of daily life’s obstacles to perceiving God’s presence? How does the Turn point the way to renewed faith through the ministry of the Holy Ghost (Spirit)?

Hopkins always experimented boldly with unusual metrical rhythms. Read the poem aloud or listen to the audio. Feel the force of stressed syllables. A Spondee is a foot in which both syllables are stressed: shook foil; bleared, smeared; foot feel; brown brink, world broods, warm breast, bright wings. Each spondee slows the verse and confers weight on themes.

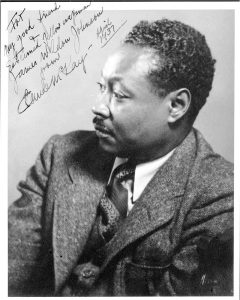

Claude McKay

|

| Claude McKay. (N.D.) Photographic Portrait. |

Born in Jamaica, Claude McKay emigrated to Harlem and became associated with the Harlem Renaissance. As a poet, he composed in highly traditional verse forms, often the sonnet. However, unlike other writers within that movement, McKay made little effort to adopt a sophisticated cool in the face of systematic racism and the violence of the “Red Summer” of 1919, a brutal eruption of violence directed against Black people in communities across America. Raging in a full-throated roar, he also recognizes the profound levels on which the blood and character of the nation flow through his deepest self. He closes the sonnet with a dark vision of a time when a nation’s oppressive pride will go the way of all tyrannies.

Claude McKay (1921). “America.”

Although she feeds me bread of bitterness,

And sinks into my throat her tiger’s tooth,

Stealing my breath of life, I will confess

I love this cultured hell that tests my youth.

Her vigor flows like tides into my blood,

Giving me strength erect against her hate,

Her bigness sweeps my being like a flood.

Yet, as a rebel fronts a king in state,

I stand within her walls with not a shred

Of terror, malice, not a word of jeer.

Darkly I gaze into the days ahead,

And see her might and granite wonders there,

Beneath the touch of Time’s unerring hand,

Like priceless treasures sinking in the sand.

How does McKay use figurative language and the Sonnet structure to rage against the social forms that bind his people? How does he use numerous Metaphors to process his ambiguous relationship to the “cultured hell” which he also loves? How does he see America’s future?

References

Allen, J. (c 1930).Claude McKay [Photograph]. Wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mackey.jpg

Hopkins, G. M. (February 23, 1877). God’s Grandeur [Poem]. In The Oxford Book of English Mystical Verse. (1917). Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44395/gods-grandeur

McKay, C. (December 1921). America [Poem]. The Liberator. Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44691/america-56d223e1ac025

Milton, K. (c 1652). Sonnet 19. In Poems etc. on several occasions (1673). Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44750/sonnet-19-when-i-consider-how-my-light-is-spent

Wordsworth, W. (1802). Composed upon Westminster Bridge, September 3, 1802. In Poems in Two Volumes. (1807). Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45514/composed-upon-westminster-bridge-september-3-1802

a Medieval poetic tradition deriving from Arab verse and 12th Century French troubadours in which a poetic voice proclaims a spiritually exalted, chaste love for an unattainable beloved, often the wife of the lover’s liege lord (feu-dal master). A conception of transcendent sexual love that remains influential in modern culture and its arts.

a 14-line lyric poem that explores a theme in stanzas with a thematic turn either between lines 8 and 9 (Petrarchan/Italian Sonnet) or between lines 12 and 13 (Shakespearian/English Sonnet).

within a poem, a repeated pattern of sounds that end lines, defining stanzaic boundaries and shaping a poem’s themes. Designated for analysis by letters: e.g. a-b-a-b, in which a-lines and b-lines end in rhyming words.

a division of within a poem that functions as does a prose paragraph and organizes the poem’s themes. Stanzas are labelled according to their number of lines and are often, but not always, defined by rhyme schemes.

a pattern of thought, value, and reflection which signifies meaning beyond the specifics of the content in a work of art

in a Sonnet, a thematic shift, often a contrast, between the themes of the earlier and closing stanzas

(Italian sonnet) a 14-line poem arranged in 3 stanzas that rhyme ab-ab/abab/cdcdcd. The 1st 2 stanzas develop a theme or problem. A thematic turn between lines 8 and 9 leads to a resolution of the theme in the final stanza.

(English) a 14-line poem arranged in 4 stanzas that rhyme ab-ab/cdcd/efef/gg. The 1st 3 stanzas develop a theme or problem. A thematic turn between lines 12 and 13 sets up a powerfully compact couplet that packs the force of a punch line.

a figure of speech that plays on meaning so that the implied message differs from the ordinary sense of the expression. E.g. hyperbole, irony, metaphor, paradox, personification, simile.