Chapter 13. Liberation from the Subject

Modern.

What does the word mean to you? Up to date? Contemporary? Avant-Garde? OK, but relative to … when? To now? The last decade?

What happens when we capitalize the first letter: Modern? Is—was—there a Modern Era in the Euro-American arts? Well, yes. It began over 125 years ago. I guess the Modern isn’t really very modern anymore.

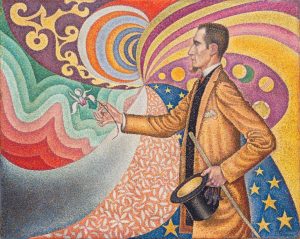

Let’s look at a Pointillist composition by Paul Signac. What do you see?

|

| Paul Signac. (1890). Opus 217. Oil on canvas. |

Hmmmm. Interesting composition, eh? Now consider the full title of the work: Opus 217. Against the Enamel of a Background Rhythmic with Beats and Angles, Tones, and Tints, Portraits of M. Felix Fenelon in 1890. Zowie! Why all those words?

Well, notice the two parts of the title: this is A) a Portrait of a specific person set against B) a flamboyant design that has no connection to the portrait or a window on Virtual Space. The background, if we can call it that, is pure Formal design: color, curvilinear Form, Composition. Signac straddles the boundary between Representation and Abstract. The portal to the Modern is opening.

Now let’s read a very short Lyric poem written by William Carlos Williams.

The Red Wheelbarrow (1923)

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens

What do we expect from a poem? A bit of Narrative. One side of a dialogue? Reflective musings on life? Some symbolic Signification?

Williams closes the door on any larger content. He instructs us to care about pure image. Color. Form. Texture. Full stop. He insists that we see that they matter, that much depends upon them.

Similarly, Signac blunts the force of Representation by carrying our eye from figure to pure form. We see a man with features distinct enough to suggest the portrait of an individual. But this magician who has pulled a flower from a hat conducts our eyes out of the mundane world and into one of pure, formal spectacle. The color palette is dominated by warm hues of red and yellow. Curvilinear, organic forms swing upward, lifting our spirits. The magician/artist presents us with an enchanted composition happy to leave the world of stoical representation behind us and open a portal to the joys of flamboyant form.

This is where Modern arts push people into zones that might feel uncomfortable. What is it? What does it mean. I need more than pure form.

The materials we explore in this Module may challenge your comfort zone. Or perhaps we simply need to connect “art” with other comfort zones. Many people who cry What is it? are happy to hang striped or patterned paper on their walls. We like lines, patterns, and colors in clothing and furniture. Why not enjoy pure form in painting?

Well, let’s see what we find. Are you up for the challenge?

References

Signac, P. (1890). Opus 217. Against the Enamel of a Background Rhythmic with Beats and Angles, Tones, and Tints, Portraits of M. Felix Fenelon in 1890 [Painting]. New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art. New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/78734?artist_id=5421&page=1&sov_referrer=artist

Williams, W. C. (1923). The Red Wheelbarrow. In Spring and All. Dijon, FR: Maurice Darantière. Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45502/the-red-wheelbarrow

a general term referring to innovative, experimental artistic movements that challenge the conventions of the day

a painting technique developed by Georges Seurat and Paul Signac that composed an image and defined contours and forms out of thousands of tiny dots of paint

in visual art, a composition that represents a human subject as an individual, meticulously capturing physical or psychological likenesses

in 2-dimensional visual art (paintings, photographs) the illusion of depth and distance projected “into” the image from the picture pane

in visual art, the elements that comprise the composition irrespective of any subject or signification: line, color, form and shape, value, texture, space, and movement

the elements, patterns, techniques, styles and structures that comprise the composition without regard to subjects, meanings, or values

in visual art, the arrangement of visual elements for expressive and aesthetic impact: unity, proximity, similarity, variety and harmony, emphasis, rhythm, balance, etc

a function of visual art which seeks to emulate a visual subject that viewers will recognize from a theoretical “real world.” Opposite: abstract or non-figurative art

visual art that makes little or no effort to represent any recognizable subject and appeals to purely aesthetic sensibilities

a style in the arts associated with the early 20th Century that emphasized formal design and the surface of the medium over any represented or narrated subject

a relatively short poem which expresses the deep reflections and poignant emotions of the poetic voice. Origin: the portion of ancient Greek dramas sung to the accompaniment of a lyre (harp).

a telling of a story using some medium: prose, poetry, cinema, painting, etc.

a secondary level of thematic meaning that opens up beyond the immediate subject of art or literature. E.g. the keys held by the figure of St. Peter in a Christian icon signify Christ’s promise that Peter would hold the keys to heaven and earth (Matthew 6.19).

in visual art, the illusion of surface feel either of A) the represented object (e.g. textures of clothing) or B) of the artifact’s media (e.g. canvas weave, brushstrokes, daubs of paint)

the range of colors selected to compose a painting’s design

in visual art, an irregular form such as a cloud or rocky terrain that suggests natural origin distinct from human artifice