11.3 Photography and Art

[Daguerreotypes] resemble aquatint engraving; for they are in simple chiaroscuro, and not in colors, but the exquisite minuteness of the delineation cannot be conceived. No painting or engraving ever approached it. … The impressions of interior views are Rembrandt perfected.

– Samuel F. B. Morse (quoted in Hirsch, p. 27)

When Count Arrago organized the showings of daguerreotypes for the Académie des Beaux-Art and the Académie des Science, the scientists were interested in its potential to document their studies with unparalleled precision. For artists, the prospect was more complex.

One of the attendees at the showings was Samuel Morse. As the inventor of the telegraph and a popular portrait painter, Morse responded to both sides of the innovation. His technical mind appreciated the precision while, as a painter, he recognized the superiority of photographic mimesis.

It will ease the artists task by providing him with facsimile sketches of nature, buildings, landscapes, groups of figures, … not copies of nature but portions of nature itself. … the public would become acquainted through photography with correctness of perspective and proportion, and thus be better qualified to see the difference between professional and less well trained work

– Samuel F. B. Morse (quoted in Coke, p. 7)

Of course, as we have seen, the quest for Mimetic precision had since the Renaissance become a core criterion by which painters were judged. Painters recognized by the academies had labored long to master techniques of modeling, perspective, foreshortening, and drawing. What if a machine came along to allow anyone instant mastery of the great goal of painting?

And the early results were mixed. Daguerreotypes provided remarkable detail and accurate perspective. But they were also fuzzy in places, often ill-lit or awkwardly composed, and, as Morse noted, lacked color. Many artists’ responses to the showings were scornful. Thomas Cole, the Hudson River School Romantic, disdained journalistic hype which seemed to suggest that “the poor craft of painting was knocked in the head by this new machinery for making Nature take her own likeness” (quoted in Coke, p. 7). The realist painter Paul Delaroche commented that “as of today, painting is dead.”

However, Delaroche’s often isolated comment was offset by a more nuanced full response. He also commented that that the invention of photography “has rendered an immense service to the arts” (Lewis, 2001). Coke (1972) has assembled a full volume of examples of painters who began with daguerreotypes or photographs, developed sketches based on the images, and then fleshed out the image in complete paintings. Coke quotes The Crayon (1855):

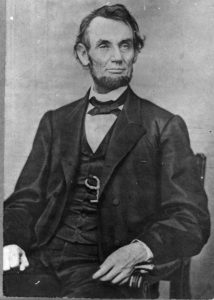

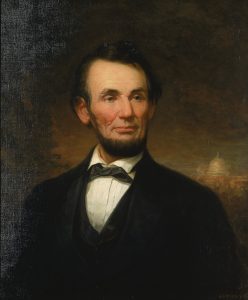

Coke (pp. 26-27) illustrates this process in a pair of images: a daguerreotype portrait of Abraham Lincoln (1864) and a painting composed many years after Lincoln’s assassination:

|

|

| Matthew Brady Studio daguerreotype (1864) | George Henry Story. (c 1916) Portrait of Abraham Lincoln. After Matthew Brady |

Painters had long begun compositions with preliminary studies, drawings often based on traced projections from a Camera Obscura. This practice honored the Renaissance valuation placed on realistic mimesis and illusionism. But as we have seen, mimetic precision is not the only goal of the artist. Numerous painters complained that a photograph’s passive precision fails to gain the creative depth of the finest paintings. Cole’s real criticism is that “the art of painting is creative, as well as an imitative art, and is in no danger of being superseded by any mechanical contrivance” (quoted in Coke, 1972, p. 7).

Increasingly, the clinical accuracy of the daguerreotype came to be seen by artists as the limitation of a sterile process that left no room for the imagination. Where was the feeling, the creative flair, the imaginative genius that could bend an image to an artist’s vision? Artists in the Romantic tradition, especially, felt that art lay, not in mimetic accuracy, but in what Wordsworth once called “the light that never was on land or sea” (Elegiac Stanzas, 1807). Photography was facing the challenge of developing its own aesthetic principles.

The print Revolution: Talbot’s Calotype Process

As the daguerreotype industry exploded on the world, the English scientist and mathematician William Fox Talbot was working on an alternate photographic technology. While the daguerreotype fixed its image on a metal plate, Talbot’s approach worked with paper sensitized with chemicals. This process had two drawbacks. Exposure times were very long. And the result was a latent, negative image—that is, a reversal of light and dark tones—which required a second processing step: printing the positive image. However, this 2nd step, initially an obstacle to the dissemination of photographic skills, actually addressed a major drawback of the daguerreotype.

A daguerreotype produced an attractive object, a unique artifact on plates lushly encased in wood and satin. But that uniqueness was also a limitation. It was very difficult to print copies. By contrast, that second step of processing opened up the world of photocopying. The negative image could be stored and later used to produce unlimited copies of an image.

In 1840, Talbot named a refinement of his process the calotype. His process was slow to gain popularity, in part because of an English patent charging significant fees for its use. But Talbot soldiered on and, in 1843, published the first photographic book. The Pencil of Light pasted copies of calotype images on its pages, demonstrating its powers and its limitations.

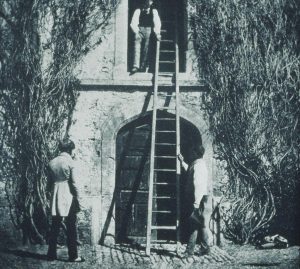

|

|

| Talbot, Willim H. Fox. (1843). The ladder. Plate XIV. The Pencil of Nature. Calotype Photograph. | Talbot, Willim H. Fox. (1843). The open door. Plate VI. The Pencil of Nature. Calotype Photograph. |

Pioneers who embraced the calotype continuously experimented with photographic technology in a trail of innovation that continues in our digital cameras today. Paper was treated in various techniques with an array of chemicals that addressed photography’s early challenges: limited sensitivity to light, slow exposure times, fuzzy detail, and high production costs. By the 1870s, a variety of paper and glass-based photographic processes were replacing the daguerreotype and expanding the new medium’s flexibility.

Precision or Imagination?

Talbot’s calotype images were criticized for their lack of the crisp detail found in daguerreotypes. This apparent weakness, however, was seen by some as an aesthetic strength. Romantic art, for example, had embraced imaginative, “picturesque” effects in which style prevailed over precise Mimesis.

Newly formed photographic societies were publishing journals that discussed not only technical innovations, but photography as an art form. In the first issue of the Journal of the Photographic Society, March 1853, Sir William Newton, previously a painter of miniature portraits, advised photographers to compose images “a little out of focus, thereby giving a greater breadth of effect” (quoted in Hirsch, 2000, p. 58). Hirsch explains that Newton was explicitly discussing photographs intended as preliminaries for painting, but he stresses that the article kicked off a debate which has lasted into our own time. Is clinical accuracy or imaginative style the goal of photography?

If photography is a passive process by which nature paints itself, where do we find the art of the camera? Of course, photography is never really passive. First, the photographer chooses the components of the scene. From the very beginning, photographers assembled figures and props in artificially staged scenes. In 1840, the wholly healthy Hippolyte Bayard created Self-Portrait as a Drowned Man to protest the government’s refusal to support him financially.

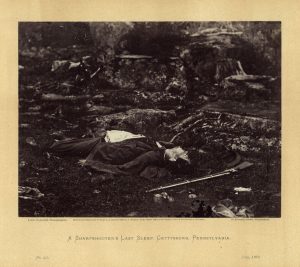

|

|

|

| Hippolyte Bayard. (1840). Self-portrait as a corpse | H. P. Robinson. (1858). Fading Away | Alexander Gardner. (July, 1863). A Sharpshooter’s Last Sleep. |

A number of early photographers staged scenes that emulated theatrical or moralistic paintings. H. P. Robinson composed a moment that would appeal to the sentiments and moralities of the day: the passing away of a young wife while her husband turns away in guilty grief. Even apparent photojournalists were known to stage their scenes. Alexander Gardner re-arranged the body of a fallen Rebel sharpshooter in an iconic daguerreotype. Eighty years later, Joe Rosenthal won a Pulitzer Prize for perhaps the most famous photo of the war: a restaging of the raising of the American Flag over Iwo Jima well after the flag actually went up.

A camera records the subjects placed before it. They may or may not be what we might call authentic. But the resulting images genuinely record the things and places, right?

Well, yes, as long as we remember that the developing process leaves room for adjustment. Sir William Newton’s suggestions for artistic blurring of the image involved adjustments of a negative “by a chemical or other process” to achieve a “picturesque effect” (quoted in Hirsch, p. 58). As their technology has evolved, photographers have always shown great creativity in manipulating images, enhancing light, shadow, and levels of detail to “introduce the imagemaker’s subjective concerns and to remove the photograph from the realm of mechanical reproduction” (Hirsch, p. 59).

The Composing Eye

While it took time to find articulation, the aesthetic of the camera is ultimately found in the challenge sensed from the earliest times by creative photographers. While the camera does much of the work, the real art of the photograph is to compose an assemblage of figures as one looks through the lens. Just as Renaissance artists composed their subjects within their window frame canvases, photographers adjust their lenses to compose their subjects with attention to line, form, light, shadow, texture, balance, and all the rest.

Let’s pause to look at two early photographs as formal compositions. We have noted that, in 1843, W. H. F. Talbot used his calotype process to print copies of photographic images in books. These images are remarkable for their compositional sophistication. “The Open Door” balances a dark, Negative Space in a wide vertical line flanked by high value stonework. A broom leaning against the wall perfectly parallels a line of shadow leading our imaginations past the door and into a dark realm of fascination and unease. Parallel, curving vines on the outside of the doorway frame a single, unlit lantern, raising further questions about light.

|

|

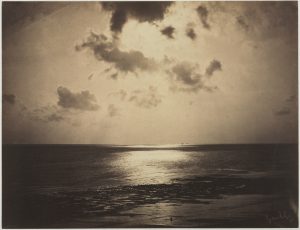

| W. H. F. Talbot. (1843). The Open Door. Calotype. | Gustave Le Gray. (1856). An Effect of the Sun, Normandy. |

A decade later, Gustave le Gray enhanced the calotype process to significantly speed up the required exposure time and thereby was able to capture action such as the waves breaking on the shore of Normandy. His composition of a wide panel of light giving definition to the vast, open space of sky, wave, and beach has the sublime grandeur of a Caspar David Friedrich. Horses and carriage are scaled down to suggest human insignificance with the grace of a Chinese landscape painting.

In these images, we see the birth of photography as an independent art form, propelled by its own aesthetic principles. The elements are the same as in all visual art. Yet the unique technology of the photographer perpetually poses a fundamental tension between the medium’s inherent accuracy of depiction with the artist’s impulse to bend materials to the imagination.

Vital Questions: Early photography

Context

Few realms of the arts embody the emergence of the modern worlds as wholly as did early photography. The camera itself was the product of technological progress and it quickly assumed a key role in documenting the industrialized world of its origin. In an innovative flood, it for the 1st time in history brought image-making into the streets and the family lives of the middle class.

Content

Early photography embraced almost every aspect of life with remarkable speed. Daguerreotypists and photographers documented scientific inquiries, shared travel images with the world, recorded historical events, and of course portrayed the faces of soldiers, politicians, artists, and family members.

Speaking analytically, we can define a photograph’s Content without regard to subject. It records subjects from a Point of View rigorously set by the frame of its lens. Every detail of objects within that frame is recorded. Everything else is cut off, i.e. cropped. This boundary is pitiless: it frequently cuts off portions of objects, subjects, even people without regard to their intended significance. In the next section, we will explore the impact of cropping.

Form

No art form has grown through such a remarkable range of technological developments as photography. We have glanced briefly at its early stages, daguerreotype, calotype, and paper prints. But the continuous sequence of breakthroughs is beyond us. We can note that, as more flexible lenses and faster, more detailed photographic paper were developed, photographers gained more control of their images.

From the beginning, though, we can notice three formal challenges faced by photographers:

- Setting up a well composed image by adjusting the point of view of the lens

- Exploiting the camera’s built-in precision and completeness of detail

- Achieving aesthetic effects by controlling light, shadow, figure, and open space

References

Barraud, Herbert. (c 1889). Portrait of Alfred, Lord Tennyson. [Photograph]. Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Museum AN 1991.304.1). https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/147576

Bayard, Hyppolite. (1840). Self-portrait of Bayard as a corpse [Photograph]. Paris, FR: Société française de photographie. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hippolyte_Bayard,_Self%E2%80%90Portrait_as_a_Drowned_Man_(Le_Noy%C3%A9),_1840.jpg

Coke, Van Deren. (1972). The Painter and the Photograph: from Delacroix to Warhol. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

Frizot, Michel [Ed.]. (1998). A New History of Photography. Trans. Bennet, S., Clegg, L, Crook, J., Higgitt, C. and Harding, C. Köln, Germany: Könneman Verlagsgesellschaft.

Gardner, A. (July, 1863). A Sharpshooter’s Last Sleep, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania [Daguerreotype]. In Gardner’s Photographic Sketchbook of the War. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/283195

Hesler, Alexander. (1860). Portrait of Abraham Lincoln. Boston, MA: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. AN 51.2779 https://collections.mfa.org/objects/159907/abraham-lincoln?ctx=89a51731-375b-4184-8ec9-ece89428b192&idx=1

Hirsch, Robert. (2000). Seizing the Light: a History of Photography. New York: McGraw Hill.

Le Gray, Gustave. (1856). An Effect of the Sun, Normandy [Photograph]. Cleveland, OH: The Cleveland Museum of Art. AN 1987.54. https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1987.54

Lewis, P. (2001). Photography and Art. In Brigstocke, H. (Ed.) The Oxford Companion to Western Art. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198662037.001.0001/acref-9780198662037-e-2037

Matthew Brady Studio. (1864). Abraham Lincoln [Daguerreotype]. Washington D.C.: Library of Congress: Prints and Photographs Online Catalog. Call Number: LC-USZ62-11178) https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2013648777/resource/

Robinson, Henry Peach. (1858). Fading Away [Photograph]. ]. Rochester, NY: George Eastman House. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Henry_Peach_Robinson,_Fading_Away,_1858.jpg

Story, George Henry. (1869). Portrait of Abraham Lincoln [Painting]. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian American Art Museum. AN 1916.3.1. https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/abraham-lincoln-23345

Talbot, W. H. F. (1843). The ladder. [Calotype Photograph]. Plate XIV. The Pencil of Nature. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Object 1994.197.3 (2). https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/289182

Talbot, W. H. F. (1843). The open door. [Calotype Photograph]. Plate VI. The Pencil of Nature. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Object. 2005.100.498. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/283068

a national association of artists in France that organized training, articulated strict rules for “fine art,” and advanced or depressed careers by selecting and rejecting submitted works for annual shows (salons).

art that strives to imitate as closely as possible the appearance of the “real thing”

committed to the late 18th and 19th Century reaction against Neo-Classical reason which sought to liberate the individual human imagination and embrace its passions, dreams, and irrational visions as sources of wisdom.

a light capturing device which projects the reverse of an image through a pinhole on a rear surface. Since at least the 17th Century, artists have used camera obscuras to create images with precise accuracy.

a representational technique in visual art that strives to imitate as closely as possible the appearance of the “real thing”

a sector of a visual composition that seems empty, devoid of clearly defined and weighted visual subjects

the material projected by art for the reader’s mind and imagination. Content can consist of an immediate Subject—e.g. a figure in a painting or a story in a narrative—and Signification, a secondary level of thematic meaning that opens up beyond the immediate subject of art or literature

the viewpoint of a work of art’s content imposed on an audience by its structure and composition. In Narrative, the perspective of the narration. In a painting or photograph, the angle and scale from which the subject is depicted.