11.1 Drawing with Light: Photography

So you are hiking in Yosemite National Park. The scenery is magnificent and your companions are dear to you. You’d like to hold the moment. You can secure a lasting image of the moment.

But how? Before about 1850, one could turn to art. But drawing and painting require skill. And professional painters were prohibitively expensive. For most people in human history, preserving images of a loved one’s face, a grand event, or a sublime landscape was unthinkable.

Yet 1800 was the time of the Industrial Revolution. Machines were performing human tasks. What if a mechanical drawing machine could transform light directly into a fixed image?

Before the Camera

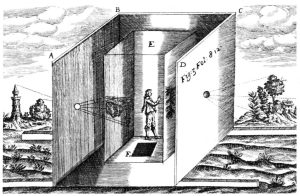

Actually, the notion of an image machine was not new. The camera obscura [Latin for dark chamber] had been used since the early Renaissance to facilitate accurate drawing. We have seen that Albrecht Dürer (15th Century) and Johannes Vermeer (17th Century) used drawing machines to achieve remarkable degrees of mimetic accuracy.

|

|

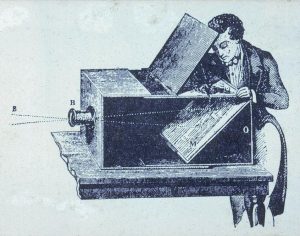

| Athanasius Kircher. (1671). Diagram of a Camera Obscura. | Drawing with portable Camera Obscura. (c 1850). |

A Camera Obscura could project an image on a wall or the back of a box. But it could not directly capture the light. An artist was still required to trace the image on paper or canvas. The play of light remained as evanescent as a moment in time.

Seizing the Light—the Daguerreotype

I have seized the light. I have arrested its flight.

The daguerreotype is not merely an instrument which serves to draw Nature; on the contrary it is a chemical and physical process which gives her the power to reproduce herself.

— Quotations widely attributed to Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre

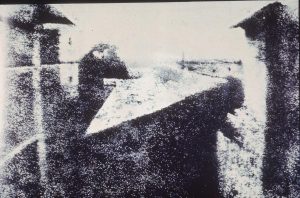

In 1816, Joseph Niépce developed a chemical process that allowed him to fix on sensitized paper an image projected directly by light. Necessary exposure times were very long and the detail left much to be desired. But in 1824, Niépce stabilized the world’s 1st photograph:

|

|

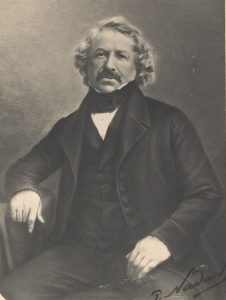

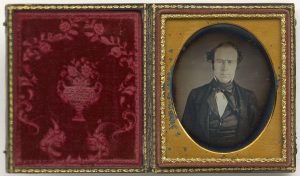

| Nicécephore Niépce. (1826-1827). View from the window at Le Gras. The first photograph? | Portrait of Louis Daguerre. 844). Daguerreotype. |

Niépce collaborated with a Parisian artist and impresario named Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre. Working separately, Daguerre developed a reasonably usable, portable device to fix images on plates of copper or silver: the daguerreotype.

|

|

| Photographer with Daguerreotype Camera. (c 1860). Tintype. | Daguerreotype equipment, process. (N.D.) |

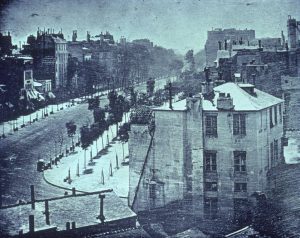

The advantage of the daguerreotype was the precision and detail of its images. Since the Renaissance, great painters were known for their ability to create illusions of visual reality. Yet even the most Mimetic painter selects, simplifies and manipulates details. By contrast, daguerreotypes recorded every detail in their scope. Early observers were staggered by their precision. Inventor and painter Samuel F. B. Morse exclaimed at the authenticity of a cityscape: “by the assistance of a powerful lens, … every letter was clearly and distinctly legible, and so also were the minutest breaks and lines in the walls” (quoted in Frizot, p. 34).

|

|

| Louis Daguerre. (c 1839). Boulevard de Temple. . | Marie-Charles-Isidore Choiselat. (c 1839). The Pavillon de Flore and the Pont-Royal. |

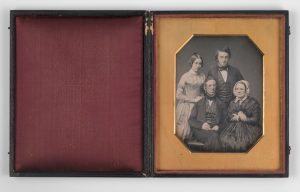

Portraiture: the Daguerreotype Industry

How many photographic images of children and loved ones does your family treasure in smart phones, photo albums, and slide shows? What if your family had not a single image to preserve the sweetness of a newborn or the vitality in aging grandparents’ faces?

Before the camera, only royalty and wealth could even imagine a means of preserving family members’ visual identities. In just a few years, the daguerreotype changed everything.

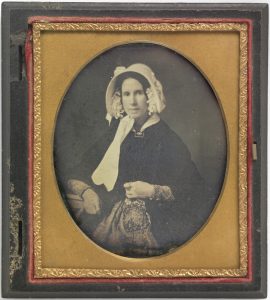

Obviously, a portrait must capture the subject’s image realistically enough to be recognizable to loved ones. The uncanny precision of the daguerreotype offered portraits more precise than those of the best painters for a fraction of the cost. While not affordable for the working classes, they were sold within a price range comfortable for middling classes.

Sitting for a daguerreotype was a challenge. Exposure times were long, so a subject had to remain stock still for perhaps a full minute. Subjects were posed against restricting back rests that immobilized them for the full exposure, one reason why daguerreotype subjects often seem dour, lifeless, frozen. But compared to the repeated, lengthy sittings endured by subjects of painted portraits, an hour’s studio session could fit into a busy work week.

A finished daguerreotype offered a family heirloom worthy of proud placement in a parlor or dining room. The plates preserving the image were tucked into wooden cases lined with satin or some other fabric. Especially in America, family portraits were sold by the thousands. By the 1850s, hundreds of daguerreotypists were operating, often out of studios producing scores of images per week, across Europe and America.

|

|

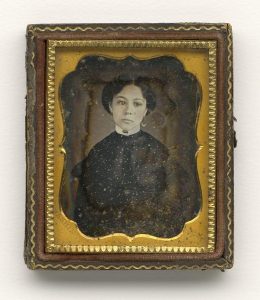

| Cooper Family Portrait. (1850). Daguerreotype with case. | Meade Brothers Studio. (1853). Unidentified Woman. |

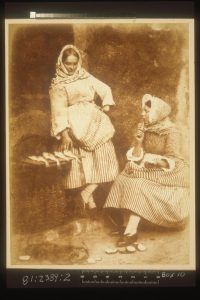

A Democratizing Medium

Early cameras encouraged artists in the new medium to record the world around them without worrying about whether subjects were fit for study according to the aristocratic standards of art academies. Calotypists David Hill and Robert Adamson composed memorable images of humble folk such as these two fisherwomen.

|

|

|

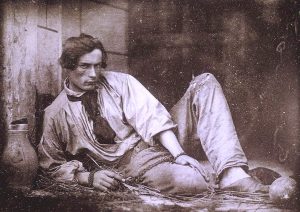

| Hill & Adamson. (c 1845). Newhaven Fisherwomen. Salted Paper Print. | Louis de Molard. (1847). A prisoner. Daguerreotype. | Charles Nēgre,. (1852). Chimney Sweeps Walking, Paris. Calotype. |

Louis de Molard took his camera into a prison to compose a striking image of chained dignity. Pioneered the art of the urban snapshot, capturing a trio of chimney sweeps in mid-step.

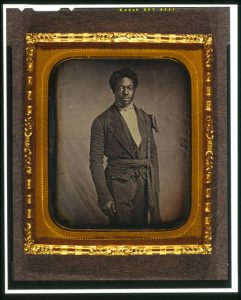

Demand for daguerreotype portraits was great enough to extend a rare opportunity for African American entrepreneurship. Augustus Washington, the son of a slave, maintained a studio in Trenton, New Jersey which welcomed clients of all ethnicities.

|

|

|

| Portrait of Clancy Brown. (1858), | Portrait of unidentified woman. (1850) | Portrait of unidentified man. (1850) |

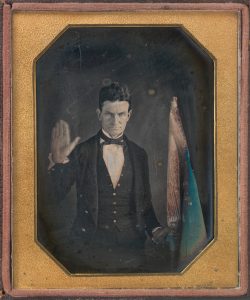

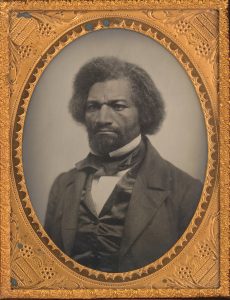

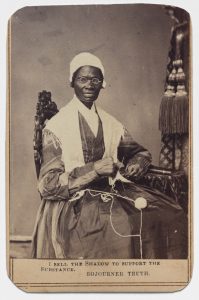

Of course, during the zenith of daguerreotype popularity, half of the states in the American Union maintained slaves. Most African Americans in the Northern states were free and many were involved in the Abolition movement which sought to eliminate slavery. Augustus Washington composed the portrait of John Brown, who in 1859 led a short-lived rebellion against the slave-holding Commonwealth of Virginia.

|

|

|

| Portrait of John Brown. (1858). | Portrait of Frederick Douglas. (1850). | Portrait of Sojourner Truth. (1864). |

By the 1850s, the abolitionist movement had been growing in the United States, Britain, and France. Heroic African American who joined in the fight after escaping slavery played major roles in the movement. Frederick Douglas became a great orator and helped shape Abraham Lincoln’s views on African American issues. Escaped slave Sojourner Truth achieved legal and political victories on behalf of African American and women’s civil Rights. Her famous “Ain’t I a Woman?” electrified the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in 1851. Fifteen decades later, daguerreotypists enable us to look these great leaders in the eye.

The Science Application

Daguerreotypes’ precision aligned them with the booming enthusiasm for science and technology. In 1839, Count Francois Arrago organized Paris showings of Daguerre’s images for the Académie des Beaux-Art and the Académie des Science. For the scientific audience, the great appeal of the technique was its detailed precision:

The daguerreotype, with its built-in wealth of detail and geometric perspective, was quickly accepted as a reliable scientific witness that also conditioned viewers to embrace photographic representation as the normal appearance of things (Hirsch, 2000, p. 44).

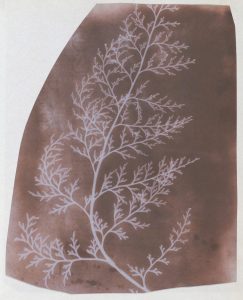

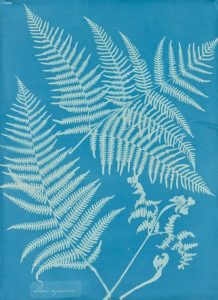

Before the daguerreotype, William Talbot had used photogenesis, a pre-photographic process to capture precise images of botanical specimens such as the seaweed [wrack] pictured below. Anna Atkins used the cyanotype, a variation on Talbot’s method, to document plants with botanical precision.

|

|

| William Talbot. (1839). Wrack [Photogenic image] | Anna Atkins, (1851). Pteris aquilina [Cyanotype image]. |

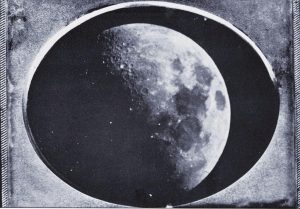

As daguerreotypes gained widespread popularity, the precision of their images attracted the attention of scientists in various fields. A daguerreotypist from the Southworth & Hawes Studio recorded one of the first surgical operations to use ether as an anesthetic. In 1851, John Whipple used the daguerreotype to contribute to astronomers’ knowledge of the moon. Early photography was seen by many as more science than art.

|

|

| Southworth & Hawes Studio. (July 3, 1850). Operation using ether for anesthesia. | John Whipple. (July 28, 1851). The Moon |

The Birth of Photojournalism

Since photography freezes moments of time, daguerreotypists wasted little time using the technology to capture current events. Journalism has traditionally been called the first draft of history, and photographs shine actual light on history’s events.

Or, in the beginning, history’s aftermath. The first photojournalists were limited by long exposure times required for an image. In 1849, Hippolyte Bayard documented the ruins of barricades set up by citizens to protect themselves from government troops during the February Revolution in Paris. Daguerreotypes worked more quickly, and in 1853 George N. Barnard arrived in time to document a great fire in Oswego, N.Y.

|

|

| Hippolyte Bayard, (1849). Remains of Barricades of the Revolution of 1848. | George N. Barnard. (1853). Burning of the Ames Mills, Oswego, N.Y. |

Still, documenting the aftermath of an event could make an impact. One of very few actions undertaken by the British Army during the Crimean War (1853-1856) was a brave cavalry charge by the so-called Light Brigade. Initial newspaper reports exaggerated the number of British dead, leading to an outpouring of patriotic fervor in Britain. Alfred, Lord Tennyson, one of the great poets of the age, bestowed immortality on the unit.

Still, documenting the aftermath of an event could make an impact. One of very few actions undertaken by the British Army during the Crimean War (1853-1856) was a brave cavalry charge by the so-called Light Brigade. Initial newspaper reports exaggerated the number of British dead, leading to an outpouring of patriotic fervor in Britain. Alfred, Lord Tennyson, one of the great poets of the age, bestowed immortality on the unit.

ALfred, Lord Tennyson. (December 9, 1854). from The Charge of the Light Brigade.

I

Half a league, half a league,

Half a league onward,

All in the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

“Forward, the Light Brigade!

Charge for the guns!” he said.

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred. …

III

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon in front of them

Volleyed and thundered;

Stormed at with shot and shell,

Boldly they rode and well,

Into the jaws of Death,

Into the mouth of hell

Rode the six hundred. …

V

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon behind them

Volleyed and thundered;

Stormed at with shot and shell,

While horse and hero fell.

They that had fought so well

Came through the jaws of Death,

Back from the mouth of hell,

All that was left of them,

Left of six hundred.

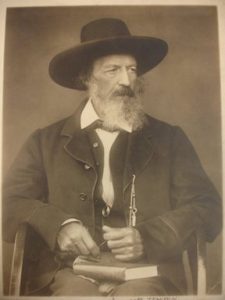

|

| Herbert Barraud. (c 1889). Portrait of Alfred, Lord Tennyson |

Though composed decades later, Richard Caton Woodville Jr.’s heroic painting captures the glory conveyed by Tennyson’s patriotic homage.

|

|

| Richard Caton Woodville, Jr.. (1894). The Charge of the Light Brigade. Oil on canvas. | Roger Fenton. (1855) The Valley of the Shadow of Death. Photograph |

But did the reality match the hype? Contemporary photographs of the Crimean campaign by Roger Fenton recorded a more accurate, mundane reality. His photograph of the valley traversed by the Light Brigade shows an ordinary road between very low rises, a far less dramatic gauntlet than the one imagined by generations of the British public.

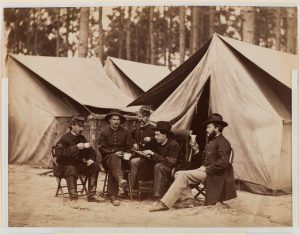

The American Civil War

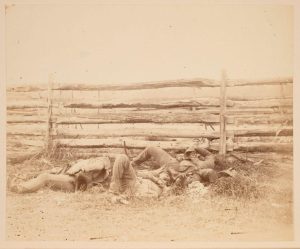

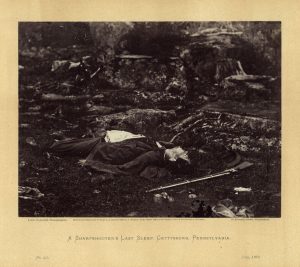

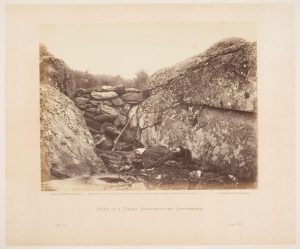

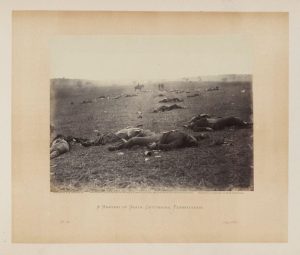

The American Civil War (1861-1865) provided a superb opportunity for the first flourishing of photojournalism. As we have seen, hundreds of daguerreotypists were deployed throughout the United States. Photographers from the famous Matthew Brady studio in New York traveled to the camps and battle sites of the Union Army. In 1866, Alexander Gardner published Gardner’s Photographic Sketchbook of the War, a lush collection of prints from his own and others’ images. For perhaps the first time in history, a widespread audience was able to see detailed evidence of war’s destructiveness.

|

|

| 5 soldiers sitting among tents (1861-1865) | Killed at the Battle of Antietam (1862) |

|

|

| A Sharpshooter’s Last Sleep, Gettysburg (1863) | Home of rebel sharpshooter, Gettysburg (1863) |

|

|

| A Harvest of Death, Gettysburg. (1863) | Ruins of Arsenal, Richmond, VA (1865) |

References

Atkins, A. (1851). Pteris aquilina [Cyanotype image]. Houston, TX: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Object 2004.2133. https://emuseum.mfah.org/objects/53525/pteris-aquilina?ctx=e82006fd7d593bee325bfacb7d433b63119008e4&idx=0#

Barnard, G.N. (1853). Burning of the Ames Mills, Oswego, N.Y. [Daguerreotype]. Rochester NY: George Eastman House. https://collections.eastman.org/objects/16871/burning-mills-along-the-river-at-oswego-new-york?ctx=b85d1c0c-7cb9-429e-b161-658d87facedd&idx=0

Barraud, H. (c 1889). Portrait of Alfred, Lord Tennyson. [Photograph]. Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Museum AN 1991.304.1). https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/147576

Bayard, H. (1849). Remains of Barricades of the Revolution of 1848, rue Royale, Paris [Photograph]. Rochester NY: George Eastman House. https://collections.eastman.org/objects/166184/royale-avenue-and-the-remains-of-the-barricades-of-1848?ctx=5cc7f85f-8573-4f55-b999-cd116059b20b&idx=0

Bayard, H. (1840). Self-portrait of Bayard as a corpse [Photograph]. Paris, FR: Société française de photographie. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hippolyte_Bayard,_Self%E2%80%90Portrait_as_a_Drowned_Man_(Le_Noy%C3%A9),_1840.jpg

Choiselat, M. C. M. (1839). The Pavillon de Flore and the Pont-Royal [Daguerreotype]. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/283103

Coke, V. D. (1972). The Painter and the Photograph: from Delacroix to Warhol. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

Cooper Family Portrait [Daguerreotype]. (1850). Unknown Artist. Washington D.C.: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. NPG. 96.86. https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.96.86?destination=edan-search/default_search%3Fpage%3D15%26edan_local%3D1%26edan_q%3DDaguerreotype

Daguerre. L. J. M. (1839). Boulevard du Temple [Daguerreotype]. Paris, FR: Musée Nationale des Techniques. Internet Archive https://archive.org/details/2-7-louis-daguerre-boulevard-du-temple-paris-1838-the-7-photos-considered-the-ol

Daguerreotype equipment and process [Diagram]. (November 18, 2013) Claudio Tommassini. Artes Visuales [Visual Art]. https://claudiotomassini.blogspot.com/2013/11/louis-daguerre-louis-jacques-mande.html

Fenton, R. (1855). The Valley of the Shadow of Death [Photograph]. Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum. https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/106R8A

Frizot, M.[Ed.]. (1998). A New History of Photography. Trans. Bennet, S., Clegg, L, Crook, J., Higgitt, C. and Harding, C. Köln, Germany: Könneman Verlagsgesellschaft.

Gardner, A. (1861-1865). Civil War Scene: five soldiers sitting among tents [Daguerreotype]. In Gardner’s Photographic Sketchbook of the War. (1866). Williamstown , MA: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute. AN 1999.5.3. https://www.clarkart.edu/ArtPiece/Detail/Civil-War-Scene-five-soldiers-sitting-among-tents

Gardner, A. (July 1863). A Harvest of Death, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania [Daguerreotype]. In Gardner’s Photographic Sketchbook of the War. (1866). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University: Harvard Art Museums AN 2013.6.1.36 https://harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/343472

Gardner, A. (1862). Home of a rebel sharpshooter, Gettysburg [Daguerreotype]. In Gardner’s Photo-graphic Sketchbook of the War. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/283195

Gardner, A. (1862). Killed at the Battle of Antietam [Daguerreotype]. In Gardner’s Photographic Sketchbook of the War. (1866). New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/259605

Gardner, A. (1865). Ruins of Arsenal, Richmond, Virginia [Daguerreotype]. In Gardner’s Photographic Sketchbook of the War. (1866). New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/286128

Gardner, A. (July, 1863). A Sharpshooter’s Last Sleep, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania [Daguerreotype]. In Gardner’s Photographic Sketchbook of the War. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/283195

Hill & Adamson. (ca. 1845). Jeanie Wilson & Annie Linton, Newhaven Fisherwomen [Photograph]. Rochester, NY: George Eastman House, 81:2389:0002. https://collections.eastman.org/objects/175079/jeanie-wilson–annie-linton-newhaven-fisherwomen?ctx=e78cc570-de01-4c9f-8dd1-567c49df9214&idx=0

Hirsch, R. (2000). Seizing the Light: a History of Photography. New York: McGraw Hill.

Kircher, A. (1671). Camera obscura [Diagram]. Ars Magna. Amsterdam. https://www.sciencephoto.com/media/997422/view/camera-obscura-1671

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre [Photograph]. (C 1844). Metropolitan Museum of Art AN 2005.100.337. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/286244

Meade Brothers Studio. (1853). Unidentified Woman [Daguerreotype]. Washington D.C.: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. NPG. S/NPG.85.235. https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.74.75?destination=portraits

Nēgre, C. (1852). Chimney Sweeps Walking, Paris [Calotype Photograph]. The Eye of Photography. https://loeildelaphotographie.com/en/charles-negre-the-book-of-a-life-by-alain-sabatier-dv/

Niépce, N. (1826-1827. View from the window at Le Gras [Photograph]. Kaninsky, Martin. (N.D.). The Dawn of Photography: Niépce’s “View from the Window at Le Gras. About Photography https://aboutphotography.blog/blog/the-dawn-of-photography-nipces-view-from-the-window-at-le-gras

Photographer with Simon Wing Daguerreotype Camera [Tintype]. (c 1860). Wikipedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Simon_Wing_daguerreotype_camera_c1860.jpg

Portable Camera Obscura [Diagram]. (c 1850). Rochester NY: George Eastman House. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Camera_Obscura_box18thCentury.jpg

Sojourner Truth [Daguerreotype]. (1864). Unknown Artist. Washington D.C.: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. NPG.78.207 https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.78.207?destination=edan-search/default_search%3Fedan_local%3D1%26edan_q%3DSOjourner%252BTruth

Southworth & Hawes Studio. (July 3, 1847 1850). Early operation using ether for anesthesia [Daguerreotype]. Malibu CA: John Paul Getty Museum. Object 84.XT.958. https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/1040HZ

Talbot, W. H. F. (1839). Wrack [Salted paper print]. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Object 282756. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/282756

Tennyson, Alfred, Lord. (December 9, 1854). The Charge of the Light Brigade [Poem]. The Exaniner. Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45319/the-charge-of-the-light-brigade

Washington, A. (1847). Portrait of John Brown [Daguerreotype]. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. NPG.96.123 https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.96.123

Washington, A. (c 1850). Unidentified man [Daguerreotype]. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.31887259

Washington, A. (c 1850). Unidentified woman [Daguerreotype]. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. https://nmaahc.si.edu/object/nmaahc_2010.16?destination=/explore/collection/search%3Fedan_q%3DAugustus%2520Washington%26edan_fq%255B0%255D%3Dobject_type%253A%2522Photographs%2522

Washington, A. (c 1858). Clancy Brown [Daguerreotype]. Washington D.C.: Library of Congress: Prints and Photographs Online Catalog. Call Number: DAG no. 1004. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004664297/

Whipple, J. (July 28, 1851). The moon [Daguerreotype]. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/263204

Woodville, Jr., Ri. C. (1894). The Charge of the Light Brigade (Painting). Madrid, SP: Palacio Real de Madrid. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Charge_of_the_Light_Brigade.jpg

a light capturing device which projects the reverse of an image through a pinhole on a rear surface. Since at least the 17th Century, artists have used camera obscuras to create images with precise accuracy.

art that strives to imitate as closely as possible the appearance of the “real thing”