9.4 Opening to the Sublime

What do you like to see in art? Beauty? How about the sublime? What does that mean?

Wordsworth’s Sublime Encounter

|

| Beaumont, Sir George Howland. (1806). Peele Castle in a Storm. Oil on Canvas. |

One day in 1807, William Wordsworth stood before a painting of Peele Castle on the Isle of Man. He realized that he had been there:

Four summer weeks I dwelt in sight of thee:

I saw thee every day; and all the while

Thy Form was sleeping on a glassy sea.

Out of this encounter, Wordsworth composed Elegiac Stanzas (1807). He contrasts the peaceful conditions of his visit with the tempest depicted by the painter and wonders how he, an artist in a different medium, would have rendered the scene:

To express what then I saw; and add the gleam,

The light that never was, on sea or land,

The consecration, and the Poet’s dream;

I would have planted thee, thou hoary Pile

Amid a world how different from this!

Beside a sea that could not cease to smile;

On tranquil land, beneath a sky of bliss.

The light that never was, on sea or land. For two centuries now, this line has resonated with artists cycling between two tasks: depicting our world and injecting an inner light of the imagination. Wordsworth’s reflection contrasts not only the visions of painter and poet, but also the times of his life. He realizes that with age his vision has grown wiser and darker:

Such Picture would I at that time have made:

And seen the soul of truth in every part,

A steadfast peace that might not be betrayed.

So once it would have been,—’tis so no more;

I have submitted to a new control:

A power is gone, which nothing can restore;

A deep distress hath humanized my Soul.

So Wordsworth returns to Beaumont’s vision of Peel Castle under very different conditions: “This sea in anger, and that dismal shore.”

Well chosen is the spirit that is here;

That Hulk which labors in the deadly swell,

This rueful sky, this pageantry of fear!

And this huge Castle, standing here sublime,

I love to see the look with which it braves,

Cased in the unfeeling armor of old time,

The lightning, the fierce wind, the trampling waves.

Standing here sublime: here Wordsworth invokes a very old word that was returning to prominence in the Romantic age.

The Romantic Sublime

In 1757, Edmund Burke published a treatise contrasting what he saw as distinct aesthetic responses:

Wordsworth’s poem contrasts the sublime and the beautiful. He remembered the castle as a lovely, peaceful, pretty sight. In Beaumont’s painting, he encounters a sublime vision of a ruined castle clinging to a rock, beset by turbulence of wind and sea. This is the sublime:

A key component in the Sublime is danger, for example heights that project a vision out into infinity. Some people seek sublime encounters with real danger by climbing mountains or parachuting from airplanes. In art, the sublime is an Aesthetic experience offering the thrill of danger but from a safe distance. Wordsworth is moved by “the lightning, the fierce wind, the trampling waves,” but he stands safely indoors, viewing a painting. Similarly, many people seek simulations of the sublime by riding on scary roller coasters or viewing horror films.

Caspar David Friedrich

In art, the Sublime opens spiritual portals into the unfathomably distant, the mysteries of infinity. During the Romantic 19th Century, painters opened gateways between our experience of the world and the forces of creation and destruction.

Caspar David Friedrich was “a German Romantic painter who, like Wordsworth, had a quasi-religious feeling for Nature, enhanced by a melancholy cast of mind” (Friedrich, Caspar David, 2015). As Wordsworth was responding to Beaumont’s sublime painting, Friedrich intentionally evoked the sublime in visions of grandeur, elevated places and destructive elements.

|

|

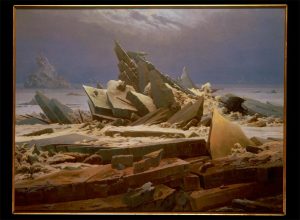

| Winter Landscape. (1811). Oil on canvas. | Sea of Ice (Arctic Shipwreck). (1824). Oil on canvas. |

Despite the academies’ disregard of the genre, Friedrich gravitated to landscape to confront viewers with daunting vistas that dwarf the human perspective in the vague menace of what Jim Anderson, my old Bethel College professor, used to call “cosmic chill.” From the safety of a museum or our computer screens, our imaginations are called out into prospects of cold infinity. Can you spot the diminutive traces of human infirmity in each of the images?

|

|

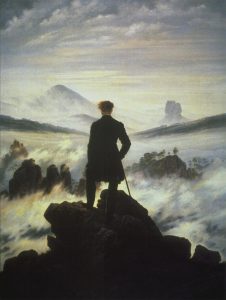

| Friedrich, C. D. (1818). Wanderer above the Sea of Mist. (1818). Oil on canvas. | Monk by the Sea (1809). Oil on canvas. |

Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Mist personifies the Romantic vision of the Sublime. The Wanderer stands on an elevated rock, gazing out into peaks that lead his imagination into infinity. Looking out, he looks within, rising above the mist of illusions that trap us in a trivial world. Looking over his shoulder, we share this vision as inspiring as it is menacing.

Few paintings open out into infinity as completely as does his Monk by the Sea. This seascape stretches high and wide, a featureless, formless, inconceivably blank portal beyond all we know. The miniscule figure of a monk stands at the boundary of what the Polish-English novelist Joseph Conrad called the “destructive element” of the sea. I hope you are thinking of those Chinese landscape paintings, with their diminutive monks contemplating mists, high places, and the mystery of the heavens.

Vital Questions

Context

The Romantics were of course not the first artists to explore transcendent visions. In the past, however, these had usually involved religious devotion. The Romantic artist did not reject religion. Indeed, Friedrich frequently included traces of Christian tradition in his visions. They are noteworthy, however, in focusing with terrible intensity on the potency of the imagination in opening a portal into infinity.

Content

A Sublime Landscape includes conventional features. Its viewpoint leads the eye out into open, empty, or menacing terrain often involving elevations. It minimizes or eliminates human figures, buildings, or possessions. Nature is represented as vast, unconquerable, menacing. Yet, like a horror flick, the effect is entrancing, seductive. With a delicious shiver of unease, we are drawn in and drawn out of ourselves.

Form

Central to its themes and effects is a sublime landscape’s open-form expansiveness. Its composition opens out into negative space that seems to push past the boundaries of the image. Contrasts of scale between vast terrains, seas, and skies and minimized humans and works are crucial to the thematic impact. In Friedrich, cold colors tend to predominate, though we will see other options when we turn to those who followed.

References

Beaumont, Sir George Howland. (1806). Peele Castle in a Storm. [Painting]. Grasmere, Cumbria, UK: Dove Cottage and the Wordsworth Museum. Wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sir_George_Howland_Beaumont_-_Peele_Castle_in_a_Strorm.jpg.

Friedrich, Caspar David. [Article]. (2015). In T. Devonshire Jones, L. Murray, & P. Murray (Ed.s), The Oxford Dictionary of Christian Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199571123.001.0001/m_en_gb0317170.

Friedrich, C. D. (1809). Monk by the Sea [Painting]. Berlin, Germany: Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. NA 9/85. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/caspar-david-friedrich/the-monk-by-the-sea-1810

Friedrich, C. D. (1824). The Sea of Ice [Painting]. Hamburg GE: Kunsthalle Hamburg. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/caspar-david-friedrich/the-sea-of-ice-1824

Friedrich, C. D. (1818). Wanderer Above the Sea of Mist. [Painting]. Hamburg GE: Kunsthalle Hamburg. WikiArt https://www.wikiart.org/en/caspar-david-friedrich/the-wanderer-above-the-sea-of-fog

Friedrich, C. D. (1811). Winter Landscape. [Painting]. London: National Gallery. AN NG6517. https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/caspar-david-friedrich-winter-landscape

Sublime. (1999). [Article]. (Ed.), An Oxford Companion to the Romantic Age. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780199245437.001.0001/acref-9780199245437-e-676.

Sublime and Beautiful [Article]. (2009). Birch, D. (Ed. ). The Oxford Companion to English Literature. Oxford University Press https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/display/10.1093/acref/9780199608218.001.0001/acref-9780199608218-e-7265?rskey=WvepeQ&result=1

Wordsworth, W. (1807). Elegiac Stanzas. Poems, in Two Volumes. London, UK. Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45516/elegiac-stanzas-suggested-by-a-picture-of-peele-castle-in-a-storm-painted-by-sir-george-beaumont

an aesthetic effect in art in which the viewer or reader experiences awe, even fear in a representation that (safely!) carries the imagination into danger, terror, darkness, solitude, or infinity

the dimension of an artistic experience that appeals to or challenges an au-dience’s sense of taste and experience of beauty, ugliness, the sublime, etc. A response distinct from “interested” concerns such as ideology, sexuality, social conflict or economics

committed to the late 18th and 19th Century reaction against Neo-Classical reason which sought to liberate the individual human imagination and embrace its passions, dreams, and irrational visions as sources of wisdom.

a visual composition that represents outdoor scenery that may or may not include human structures. Often an exercise in perspective and depth of field, with receding zones: foreground, middle distance, and deep distance.