Chapter 4: Reading College-Level Materials

Many students dislike reading for any number of reasons. Some find it boring. Others learned that, in high school, they could get by just attending class and Googling important concepts. Others struggle to pick out main ideas so they don’t “get anything” out of it. This chapter will help you have conversations with students about reading effectively and will provide you with suggestions to pass on to students that will make it more likely they will not only read, but “get something” out of it.

Reading and notetaking go hand-in-hand. Students who read successfully will also have a notetaking style of some kind to keep track of what they have learned. However, students also need to take notes in other situations, such as when they listen to lectures and many of the techniques students might use to take notes over readings are the same ones they could use to take notes over lectures. Lecture notetaking techniques will be covered in Chapter 5: Notetaking on Lectures.

Want the Resources?

Each resource is downloadable as a Word doc. Look for the link at the end of the chapter.

Each resource is downloadable as a Word doc. Look for the link at the end of the chapter.

4.1 Beliefs and Challenges Students Might Have Related to Reading

Students may have the following beliefs about reading that prevent them from making appropriate reading choices:

- They believe memorizing and learning are the same thing. Many students focus on memorizing facts and terms. They do not notice the structure of texts– for example, if they are reading a textbook, they do not notice headings, review questions, chapter outcomes, etc. They also do not notice the author’s clues about organization– for example, they do not notice that an author’s goal is to compare and contrast two or more things, describe the steps in a process, etc.

- They do not make inferences, draw conclusions or notice how information in one part of a reading relate to other parts. Again, because students focus on facts and memorization, it does not occur to them to that they might be asked to apply what they learned to solve a problem. For example, in an EMS class, a student might memorize the definition of hypoglycemia, but be unable to answer a test question such as, “You arrive at a scene to find a seventeen-year-old girl who is sweating, has clammy skin and appears disoriented. Her mother, who called 911, reports that her daughter burst into tears for no reason. What should you do to assess this patient?” Students who focused on memorizing the definition of hypoglycemia expect to be tested on the definition. They are unprepared to take what they learned about it, recognize the symptoms in a scenario-based question and used that knowledge to problem-solve (i.e. decide what action to take). Often, to answer such questions students much take information from multiple parts of a reading– a skill they do not have.

- They believe fast is best. In most aspects of our culture, speed is desirable, so students translate that belief to reading. They think they are poor readers if it takes longer than a hour to read a chapter. Some students are so committed to speed that they do not pay attention to whether or not they understand the reading.

- They believe that notetaking “slows them down,” and/or they have a better memory than they do. Many students might read but not take notes. Some students don’t take notes because it makes reading take longer, while others don’t because they think they will remember what they read.

- They believe what they learned about reading novels applies to textbooks. Most students learn to read novels and stories early in life. In fourth and fifth grade, when they begin to read traditional textbooks, they are not formally taught that reading different kinds of sources requires different strategies. The biggest challenge students have in transitioning from novel-reading to textbook reading is that they want to read textbooks in the same linear way they read novels. They don’t “skip” to the end of a chapter to read review questions or lists of important vocabulary words, they don’t flip back to the beginning of the chapter to check their understanding of the chapter outcomes.

- They do not have strategies for “correcting” confusion. Students might not have practice determining if what they are reading confuses them. If they do realize they are confused, they don’t always have strategies to resolve confusion. For example, they don’t know how to pick apart a paragraph to look for a main idea, or generate some possible resolutions to their confusion and determine which possibility is the most likely.

- They believe reading should be done at one time. Students commonly read entire chapters, articles, etc. they day before they are due because they will be “fresh” in their minds. Other students, when they realize they have an exam on a Thursday, will take Wednesday off from work so they can spend the entire day studying for their test. They do not understand that the human brain is not wired to learn 35 pages worth of new material all at once.

4.2 Discussion Points about Reading

- Sometimes students benefit from hearing that reading can be boring and difficult– and that some reading is boring and difficult not matter how good a reader you are. Sometimes they benefit from hearing that even professional learners, like their tutors and their instructors, have read things that are difficult and boring.

- Students benefit from hearing how the brain and body work together to learn new material So they can set themselves up for success. Here is what they would benefit from knowing:

- People can learn 4-9 new concepts at one time. The more unfamiliar the material is to the person, the fewer (closer to 4) concepts they can learn at a time. This is why students cannot read and understand a 35-page chapter at one sitting and why they should divide reading up into do-able chunks.

- Students forget a huge percentage of what they read and hear if they do not have a notetaking system that they review regularly.

- Adequate sleep helps people create memories, so skipping sleep to study usually backfires.

- Students often ignore textbook features (like learning outcomes, review questions, etc.) because they want to jump into the reading, and because novel and story reading don’t explicitly teach them how to use textbook features. Students can benefit from knowing what features their textbooks have and how to use them, and from hearing that the process of reading a textbook is different from reading a novel or a story.

- Students don’t always see how textbooks “work.” For example, they don’t notice that most chapters are dividing into several sections, and each section has subsections and sub-sub-sections. It can help them use the textbook effectively if they learn to notice how chapters are organized.

4.3 Reading Resources

This chapter features the following resources:

- The Warmup, Workout, Cool down Reading Steps for Textbooks

- The Matrix Notes

- Graphic Organizers

- Tips for Reading Novels

- Tips for Reading Scholarly Sources

- Tips for Reading Essays and Popular Articles

The Warmup, Workout, Cool Down Reading Steps for Textbooks

Overview

The Warmup, Workout, Cool Down Reading Steps for Textbooks resource helps students understand that textbook reading is different from reading novels, and it introduces them to the idea of using textbook features (i.e. headings, subheadings, review questions, chapter outcomes) strategically to enhance learning.

How It Helps

This resource will help students with the following aspects of executive functioning:

Task initiation— This resource might help students who get overwhelmed when they see they have a long, complex chapter to read because it provides them with a clear strategy to begin their reading.

Task initiation— This resource might help students who get overwhelmed when they see they have a long, complex chapter to read because it provides them with a clear strategy to begin their reading.

Self-Monitoring— Because this resource explicitly directs students to stop periodically and answer review questions or determine if they have achieved learning outcomes, it can help students notice whether or not the comprehend reading.

Metacognition— This resource asks students to consider the purpose of the chapter as well as the purpose of each section within it. As students use clues from the text to determine a chapter section’s main purpose, they see how the facts and terms they are learning fit within a larger framework of knowledge.

Metacognition— This resource asks students to consider the purpose of the chapter as well as the purpose of each section within it. As students use clues from the text to determine a chapter section’s main purpose, they see how the facts and terms they are learning fit within a larger framework of knowledge.

Warm-up, Work-out, Cool-down Reading Steps for Textbooks

Follow the steps below to increase your reading comprehension. The Warmup, Workout, Cool Down strategy works best for textbook reading because it helps you notice and use textbook features. Textbook features are anything the authors have added to the textbook to make it easier for you to pick out main ideas—they include headings, subheadings, learning objective questions, review questions and illustrations.

|

WARM UP |

Pre-Read the entire chapter by doing the following:

Goal: To get a good sense of what concepts and terms you will have to know, and what you will have to do with them– i.e. will you need to understand the steps in a process? Understand the differences between two or more things?

|

|

WORK OUT |

Read the First Chapter Section Step 1: Pre-read just the first section of the chapter by doing the following:

Select a notetaking style that fits the purpose of the chapter section. For example, if the goal of a section is to compare two or more things, make a chart. If the goal is to show steps in a process, make a time line. Goal: To get the best sense possible of what you will learn in just that section, and to pick a notetaking style that will help you remember the concepts. Step 2: Read the chapter section and take notes. Make sure your notes answer questions from the learning objectives, or the questions you made out of headings. Goal: To take notes that contain the important information.

|

|

COOL DOWN |

Review the section before you move on the next by doing one of the following:

Goal: To make sure you the best understand you can have of this section of chapter before moving on the next section of the chapter, and to make a plan to resolve any confusion you have. |

The Matrix Notes

Overview

The matrix notes are a notetaking style that helps students recognize and use textbook features like headings, but matrix notes can be adapted to read other kinds of materials, such as articles. It helps students recognize that knowing terms and definitions isn’t all there is to reading.

How it Helps

The matrix notes will help students with the following aspects of executive functioning:

Self-Monitoring– The structure of the matrix notes will help students monitor their understanding. For example, they will be able to recognize whether or not they have learned the outcomes for the chapter, and they will have to discern “concepts” from “terms and facts.”

Self-Monitoring– The structure of the matrix notes will help students monitor their understanding. For example, they will be able to recognize whether or not they have learned the outcomes for the chapter, and they will have to discern “concepts” from “terms and facts.”

Metacognition— Matrix notes might help students recognize that by the time they are done reading they need to be able to “do” something– i.e. name the steps in a process, or explain the differences and similarities between two things, people, etc. It will help students move past memorizing terms.

Metacognition— Matrix notes might help students recognize that by the time they are done reading they need to be able to “do” something– i.e. name the steps in a process, or explain the differences and similarities between two things, people, etc. It will help students move past memorizing terms.

Matrix Notes

The matrix notes can help you decide what to take notes on. Below is a chart that shows you what should go in each column. After the chart is a blank chart you can complete for yourself. NOTE: it is often helpful to turn your digital document or paper notebook so it is in “landscape” format. If you love the matrix notes and want this to be your notetaking style from now on, it is possible to buy “landscape notebooks.”

Chapter number and title: Heading: Pages:

| Subheadings | Terms and Facts | Concepts |

| Most textbook chapters are divided into sections that have headings and subheadings. Above, you wrote the heading. In this column, write the subheadings.

|

In this column, write down terms and definitions from this section that seem important to know. You can either:

Write the terms and definitions first prior to reading the section or write down the terms and definition as you come to them. Experiment with both ways to see what works for you. Make sure you line up terms and facts and concepts with the subsection you got them from so when you study later, you can see what section or subsection a particular term came from. |

In this column, write the concepts you are learning from this section. Here are three ways to do that:

|

| When you come to the next subheading, start a new box so that it will be clear which terms and concepts came from which section. |

Graphic Organizers

Overview

Graphic organizers represent information in such a way that students can see the overall purpose of the reading, or the relationships between the pieces of information in the reading. For example, if the purpose of a reading is to help students understand the differences between a plant cell and an animal cell, taking notes in a comparison chart will make that overall purpose clearer.

Using the graphic organizers is possible in a lecture, but difficult for students since it might not be clear until a few minutes into a lecture what the overall purpose of it is. Faculty could help students determine purpose by stating it early in the lecture, or by drawing a graphic organizer on the board to help students see the bigger picture. Many written resources, especially textbooks, make the purpose more explicit through headings, graphics, learning objective questions and the like.

How They Help

The graphic organizers can help students with the following aspects of executive function:

Metacognition– The graphic organizers can help students for whom the overall purpose of a reading or lecture is not clear. Many students have been trained to notice and focus on pieces of information, like definitions and dates, but they have a harder time see the role the information/ definition plays in the larger purpose of the lecture or reading. Having a visual representation of the information can help students recognize the bigger the picture.

Metacognition– The graphic organizers can help students for whom the overall purpose of a reading or lecture is not clear. Many students have been trained to notice and focus on pieces of information, like definitions and dates, but they have a harder time see the role the information/ definition plays in the larger purpose of the lecture or reading. Having a visual representation of the information can help students recognize the bigger the picture.

Self-Monitoring– Graphic Organizers give students another tool to assess how well they understand concepts because graphic organizers help students move beyond looking at a specific fact or term to seeing how that fact or term connects to others. This allows students to begin asking questions such as “What caused what?” “How is X different from Y?” “What are the steps in the process of X?” or “What are different types of Y?” As students begin to ask these questions, they can assess their own understanding.

Self-Monitoring– Graphic Organizers give students another tool to assess how well they understand concepts because graphic organizers help students move beyond looking at a specific fact or term to seeing how that fact or term connects to others. This allows students to begin asking questions such as “What caused what?” “How is X different from Y?” “What are the steps in the process of X?” or “What are different types of Y?” As students begin to ask these questions, they can assess their own understanding.

Graphic Organizers

Sometimes it is easier to take notes on reading using graphic organizers– which are simple charts and pictures. The advantage to graphic notes is that you can sometimes see relationships between ideas that aren’t clear from notes that are taken in a regular paragraph format.

Cause/Effect Chart

Sometimes it is important to understand what thing or things caused something else to happen. How did one event or idea lead to another? How does a virus cause disease? How does a recession affect shopping habits? What weather conditions cause tornadoes? Here is a way to take notes when it seems the main point is to help you understand how one event led to another.

| Cause(s):

|

| Effect(s):

|

| Why It Matters:

|

Compare/Contrast Chart

Sometimes, a major goal is to compare two or more people, places, ideas, events or processes. A T-graph allows you to compare two or more things side-by-side so it is easier to keep similarities and differences straight. Just add more columns the more things you need to compare or contrast.

| Person, Place, Idea, Event or Process 1 | Person, Place, Idea, Event or Process 2 |

| In the box, list the characteristics of the person, place, idea, event or process so you can see how they are different from and similar to the person, place, idea, event or process in the next column.

Highlight similarities in one color so you can tell at a glance what the two things have in common.

|

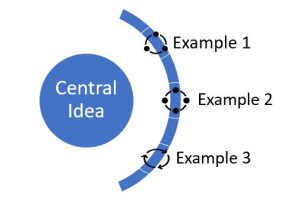

Examples or Types Concept Map

If it seems important to understand that there are multiple types of or examples of something– i.e. multiple types of volcanos, several types of clouds, a number of ways to set up a business, it might be easiest to take notes in a concept map. A concept map allows you to put a central idea in the middle (i.e. “types of volcanos”) and in bubbles around that center, you would name and describe each type of volcano.

Steps In a Process

Sometimes the goal of a reading is to help you understand a process– how a cell divides, or blood pumps through the heart. The process a bill takes to become a law, how to calculate the slope of a line. A time-line chart can help you remember the steps in a process, or the steps leading up to an event. The timeline can be vertical or horizontal, and you can include as many or as few steps as you need.

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | Step 5 | Step 6 | Step 7 | Step 8 | Step 9 | Step 10 |

Who/What/When Chart

If you are learning history, or any other subject where people are doing things, consider taking notes in a who/what/when graph. Who/what/ When graphs can also be useful when you are trying to keep track of characters in a novel. You can add, delete or change the questions in any way that suits your subject.

| Who | What | Where | When | How | Why | Who Cares? |

Tips for Reading Novels and Non-Fiction

Overview

Students expect to read novels in Literature Classes, and English faculty are prepared to discuss how to read them, but faculty in other disciplines might assign a novel that closely relates to course content– for example a history instructor teaching a class focusing on societal changes caused by World War II might assign a novel that features characters adjusting to life after the war. Students don’t always get the connection between the novel and the concepts in the class.

How It Helps

This resource may make it more likely students will connect novels and non-fiction with course concepts because it first asks them to consider exactly why they are reading the book in the first place and secondly, it provides them with a simple tool to take notes.

Self-Monitoring– If students are made aware that they are reading a book in order to more thoroughly understand concepts they are learning in the course, they will have the tools to “monitor” their reading by asking themselves, “What, if any concept(s) does the chapter I just read relate to?” “What, if any, examples of an important course concepts did I see here?” “How does what I read in this book connect with what I’m learning in lecture? In the other materials I’m reading for this course?”

Self-Monitoring– If students are made aware that they are reading a book in order to more thoroughly understand concepts they are learning in the course, they will have the tools to “monitor” their reading by asking themselves, “What, if any concept(s) does the chapter I just read relate to?” “What, if any, examples of an important course concepts did I see here?” “How does what I read in this book connect with what I’m learning in lecture? In the other materials I’m reading for this course?”

Metacognition– As students are explicitly taught to look for important themes, concepts, or examples of concepts in the book they are reading they will build metacognitive skills. They will also be able to look ahead– “What am I supposed to be able to know or do once I’m done with this book?”– and select study activities that will prepare them for what is coming up.

Metacognition– As students are explicitly taught to look for important themes, concepts, or examples of concepts in the book they are reading they will build metacognitive skills. They will also be able to look ahead– “What am I supposed to be able to know or do once I’m done with this book?”– and select study activities that will prepare them for what is coming up.

Tips for Reading Novels and Non-Fiction

If you have been assigned a novel or a work of non-fiction, it usually it is because the things that happen to the characters in the novel relate in important ways to concepts you are learning in the class. For example, if you are in an African American History course, you might read a novel about an African American family who lived during the Civil Rights movement so you can see how the Civil Rights movement affected that family.

How to Read Books: Novels and Non-Fiction

Step 1: Read the syllabus and all assignments related to the novel. Even if your first writing assignment about the novel isn’t due for several weeks, read it anyway. Why? Because the assignment will give you clues about what to notice when you read the novel. Let’s say, in your Psychology class, you are reading a novel about a woman who suffers from major depressive disorder. One of the points of the class is that people with mental illnesses experience barriers to getting help and that society can and should do a better job of removing those barriers.

Even though the assignment over the book isn’t due for three weeks, you read it and here is the prompt for the paper you have to write: “In the novel, the main character, Lydia, suffers from depressive disorder. In this class, you are learning about common barriers people with mental illnesses face to receiving treatment. Select three barriers our character faces, describe them, explain why they are common barriers and suggest ways to overcome them.”

Now you know what to mark, underline and note when you read in the novel– the barriers to receiving treatment.

If it isn’t clear why you are reading the book for your class, it is okay to ask your instructor, a tutor or other students.

Step 2: Develop a notetaking system. Usually, for novels, simply underlining or highlighting important passages is good enough, but in a 328-page novel, how are you supposed to remember where you underlined what? Here is a simple way to do it:

Fold a sheet of paper in half so it fits in the book. Clip a pen to it and use the pen/ paper as a bookmark. Set up the piece of paper something like this:

|

Chapter/ page |

Brief summary of action |

Connection to important concept |

|

chapter 3 page 51 |

Lydia tells co-worker she has from depression and co-worker tells her to cheer up and look on the bright side of things. | One barrier we are learning about is people don’t understand depression and say things that make it seem people can “snap out of it.” |

Try to write briefly so you don’t overwhelm yourself with information. If “Brief summary of action” and “Connection to important concept” are not good column headings for your class, replace them with headings that fit better.

Most instructors are happy to help students study and do homework more effectively. Consider showing your notetaking system to your instructor to see what they think of it. They may have some really great suggestions.

Step 3: As you get closer to the assignment/test/ presentation, etc., sort out your evidence. Go through what you have written on your sheet of paper and put stars next the “evidence” you think will relate most closely to the assignment you need to do and/or will be the easiest to write about.

Tips for Reading Essays and Popular Articles

Overview

Students are often assigned essays or articles to read for classes, but they are not always given direction about how to read them. As a “default mode” students often underline and mark parts of the article or essay they found interesting, as opposed to noticing the reading’s major points or arguments. This resource will help students identify the article structure and purpose.

How It Helps

This resource may make it more likely students will notice an author’s main points and arguments, and it gives them guidance about how to take notes.

Self-Monitoring– If students are encouraged to look for an author’s purpose and main points, they will be better able to monitor their own understanding of the source. Having guidance about notetaking situation can also help them monitor their own understanding.

Self-Monitoring– If students are encouraged to look for an author’s purpose and main points, they will be better able to monitor their own understanding of the source. Having guidance about notetaking situation can also help them monitor their own understanding.

Metacognition– As students are explicitly taught what to look for in an essay or article, they may build metacognitive skills because they will begin to see how the reading “works” as a whole to make the author’s argument as opposed to seeing it as a disjointed series of statements or facts.

Metacognition– As students are explicitly taught what to look for in an essay or article, they may build metacognitive skills because they will begin to see how the reading “works” as a whole to make the author’s argument as opposed to seeing it as a disjointed series of statements or facts.

Tips for Reading Essays and Popular Articles

As a rule, the goal of the author of an essay is to get readers to understand their viewpoint and/ or connect with them emotionally. The goal of an article is to inform readers about an event, situation, person or idea. Unless an essay or article is really long, try to simply take notes on the document itself– i.e. write in the margins or on sticky notes you place next to information you want to mark. If the essay or article is in electronic form and you don’t want to print it, see if you can use an online note-taking app of some kind.

Step 1: As you read the essay or article, mark the following types of information:

- Things that confuse you (places where you aren’t sure what the point is)

- Places where it seems the author is making an important conclusion

- Places where it seems the author is justifying or providing reasons for their conclusion

- Any sentences that give you clues about the structure of the article. Below are examples:

- Number sentences: i.e. “There are three reasons by we should change XYZ law . . . .” Sentences like this tell readers that the author will likely list and discuss each reason.

- Comparison sentences: “Similar to,” “different from” or “There are important similarities/ differences between X and Y” indicate that an author’s purpose is to compare and contrast two or more things.

- Cause/ Effect: “X caused Y” or “X led to Y . . .” shows that the author’s purpose is to show how one thing caused another.

- Process: “The first step is to . . . . .” or “The first thing that needs to happen is . . .”indicates that the author wants you to understand process.

- Anything that reminds you of another source you are reading for class.

- Anything that touches you personally because you can relate to it

Step 2: Come up with a color coding or a symbol system for each type of information above. For example, if something confused you, put a question mark by it. If something seems to be an important conclusion, write “conclusion” beside it, etc. Or, if you like colors, highlight all confusing things in yellow, all conclusions in pink, etc.

Step 3: When you are done reading the essay or article ask yourself this question: “What major conclusion or conclusions does this author come to?” and/or “What do they want to persuade readers to believe or do?”

Once you’ve answered the question that seems the best fit for your article, make a list of reasons why you believe this is the author’s main conclusion. Here is a made-up example: let’s say you read an article that makes the point that American school lunches are very unhealthy compared to the school lunches offered in other parts of the world and that has led to a series of health and behavior issues for school children. You could write something like this:

Main Conclusion: American School lunches are unhealthy compared to many other countries and this has led to health issues.

Reasons the author gives to support this conclusion:

- America spends less on school lunches than other countries, which results in low quality foods high in fat, sugar and salt.

- American children have higher rates of obesity than children in other countries.

- American children suffer in greater numbers from behavioral problems than children in other parts of the world.

- These behavior problems can be linked to diet.

Tips for Reading Scholarly Articles

Overview

Scholarly articles are hard for everyone to read, let alone students in their first semester of college. Perhaps more than any other kind of academic reading, scholarly articles require students to understand their structure and its purpose in order to understand them. Scholarly articles also initiate students into discourse communities and systems of though common in high education. This resource helps students notice, understand and use the structure of a scholarly article as well as provide them with concrete steps to take to take notes.

How It Helps

This resource may make it more likely students will notice and use the structure of a scholarly article to make sense out of it.

Self-Monitoring– Students are encouraged to look at the article part-by-part and engage in an activity designed to enhance their understanding of it. The activities will help students note where they are “stuck.”

Self-Monitoring– Students are encouraged to look at the article part-by-part and engage in an activity designed to enhance their understanding of it. The activities will help students note where they are “stuck.”

Metacognition– As students are explicitly taught what to look for in scholarly articles, they may build metacognitive skills because they will begin to see how the reading “works” as a whole.

Metacognition– As students are explicitly taught what to look for in scholarly articles, they may build metacognitive skills because they will begin to see how the reading “works” as a whole.

Tips for Reading Scholarly Articles

Scholarly articles have unique features and a unique function. As you already learned, they are hard to read because they are written for a professional audience. However, it helps to read these challenging articles if you understand how they work. Scholarly articles have a certain structure—and you can use it to help you figure out what the article is doing. In the next pages, you will read about the structure of these articles as well as suggestions about how to read each part.

The first step in successfully reading a scholarly article is to give yourself enough time. Even a short scholarly article might take longer to read than you think it will. If you think you can read a scholarly article in just an hour or two, rethink that. Give yourself opportunities to read the article in stages, and even read it multiple times.

Parts of a Scholarly Article

Most scholarly articles have distinct parts. Some common parts are:

- The title

- The abstract (A short paragraph at the beginning that summarizes both the studies the authors did and what they learned from them

- The introduction

- Methods (Descriptions of studies or experiments the authors conducted)

- Discussion/ Conclusion (The authors sum up what they learned and why what they learned is important)

Step 1: Read the Title

Scholarly articles sometimes have long titles and words you don’t know. If you don’t know the words in the title, look them up—and make sure to read all the definitions of the word since sometimes a word means something in “regular English” but something else in a scholarly article.

Next, re-write the title in “plain English.”

Step 2: Read the Abstract

Most scholarly articles have an abstract– a paragraph-long summary at the very beginning of the article, usually labelled “abstract.” It includes information about what the authors hoped to learn, how they went about learning it and what their major conclusions were. The reason authors write abstracts is so that other researchers can read that one paragraph and decide whether or not they want to read the entire article.

Read the abstract, and when you are done, do the following:

- Make a statement about what you will learn in the article

- Write two questions you expect/hope the article will answer

- Write between 1 and 5 words you think you need to know the definition of in order to understand this article

- If possible, compare your ideas about what will be in the article with a classmate.

Step 3: Read the Introduction

Most scholarly article have an introduction—and the point of the introduction is usually to do two things:

- Summarize a bunch of research on the topic. The author of the article does this so you can see them as an expert who has done a lot of research, and also to sum up in a few pages what the current research on that topic is.

- Explain why the scholarly article is important. Authors usually write something to help you understand how their article fits into the research. For example, let’s say that you are reading an article written by authors who are researching how social media affects children. Let’s say the researchers notice there is a ton of research about how social media can harm teen girls’ self-images, but they notice very little research has been done on younger children, so they have decided to study girls who are 8-10 years old. They will explain in their introduction that their research matters because it focuses on a group that has not been studied very much.

Do the following while you read the introduction:

- Underline or highlight three to five things you find interesting

- Put a star next to three to five sentences/ paragraphs you think get at a main idea

- Mark ANY words, sentences, phrases, etc. that help you understand the article’s purpose or help you understand the structure of the article. Here are examples of what to look for:

- Sentences that give numbers: i.e. “There are three reasons why XYZ happens . . . “ or “this research explores the four reasons why students prefer online learning.”

- Sentences that suggest a shift in thought: i.e. “For decades, educators have believed that suspending students is an effective way to punish them, but new research proves that it is harmful to students.” Or “The idea behind suspending students is that suspension will make them want to behave better, however, the opposite is often true.”

- Words to look for include “but,” “however,” “in conclusion,” “on the contrary,” “on the other hand,” “in addition to.”

Step 4: Read the Rest of the Article

By now, you are probably at the “methods” or “methodology” section of the article. Different authors will use different titles, but usually, the section of a scholarly article that is just after the introduction focuses on how the authors did their research. There may be many subheadings in this section, and those will vary widely by the article, so focus on what the author’s purpose is in this part of the article.

Let’s pretend you are reading an article called “Rethinking School Suspension: Is the Punishment Worse Than the Crime?” The author of the article is arguing that suspending students from school is not a good way to punish misbehaving students. (Note: while there maybe research on this topic, this particular article is made up). There are three basic ways the methods or methodology sections can be set up. They are described below:

- The authors might describe and summarize qualitative studies the author(s) did themselves—Qualitative means that the author relies on non-numerical information (interviews, open-ended survey questions, journal entries written by the people who are being studied, observations) to make a conclusion or recommendation. If the author of our fictional article on school suspension interviewed suspended students or the educators who suspended them, that would be an example of a qualitative study. As you examine this section of your article, does it seem the author relied on interviews or open-ended survey questions?

- The authors might describe and summarize quantitative studies the author(s) did themselves. Quantitative means numbers. If the author focuses on quantitative research, they will determine what percentage of students who are suspended a certain number of days out of the school year earn low GPA’s, or don’t graduate from High School at all. They might explore if students who end up on suspension go on to get into more serious trouble, and, if so, what percentage and what kind of trouble– and they will use data to make their point. As you read your article, do you see lots of statistics? Some scholarly articles have several pages of data. If you haven’t had statistics, you won’t understand it. Don’t stare at it endlessly—staring at data won’t make it clearer. Get what you can out of it and move on.

- Summarizes a ton of research done by others, then makes a recommendation. Some scholarly articles don’t contain any studies the authors did themselves—rather, they use research already done. For example, a scholarly article about why suspending misbehaving students is a bad idea will summarize many articles or studies that explain why suspension harms students and how other ways of dealing with misbehaving students is better. If an article has summaries of other people’s research, it is called a literature review, which might be a confusing term since you probably associate literature with novels, poems and short stories.

Look through your article and decide if it seems to be mostly qualitative, quantitative or a summary of lots of other research. After reading it, what does the author basically seem to be saying?

Step 5 Read the General Discussion

At the end of the article, you will see a heading that might say “Discussion” or “Conclusions” or “Recommendations.” These sections of the article sum up the author(s) main points. Here is the type of information you will find in these sections:

- Major conclusions of the research or experiments.

- Things the author(s) would do differently if they had an opportunity to do more research or do the experiment again.

- Explanations of how this article fits into what else is being said about this topic. For example, if authors researched how nitrates affect ponds in northern Minnesota, but in their research, they find that most studies focus on lakes, they would explain that their research adds to our understanding of nitrates in different kinds of water sources.

- Ideas the author(s) have about what should be done now that we know what we know. For example, if authors were researching why students don’t complete college and 60% of non-completers they interviewed said they would have continued with college if they had more money, then the authors might recommend that schools do a better job helping students understand and get financial aid.

As you read these last paragraphs of the article, write down five statements/ conclusions the author(s) is making about this topic. If it helps, think of it like this: If you had to summarize the main ideas of this article for someone who hadn’t read it, what would you say?

4.4: Ideas for Using Reading Resources

If You Are A Tutor . . .

- With your student, read through the “Warm Up, Work Out, Cool Down Reading Steps” and talk to your students about which activities would be most helpful for them. Help them create a written plan that lists the activity or activities they chose for each step. When they return for a second meeting, ask them which activities they found useful, which ones weren’t and whether/ how they would like to change their reading activities in the future.

- Prepare to address how reading “works.” Many students will argue that Pre-reading and Cooling Down waste time—they simply need to get reading done. If your student says this, explain that pre-reading saves time because it helps them decide what is important and what to take notes on. The cool down makes information “stick” so they are less likely to need to re-read. Explain that their brain is like a potted plant. Plants need water, but if you pour too much water in at once, the water is wasted—it runs over the side of the pot or out the drain holes at the bottom since the soil can only absorb so much water. Their brain is like the soil. It can only hold so much information. If they keep dumping concepts into it, those concepts will “overflow” (be forgotten) and need to be re-learned. The cool down is one way to prevent this from happening.

- If your students are reading things that aren’t textbooks, use whatever is useful from this chapter in creating a specific reading plan for your students that includes a schedule– i.e. how many pages a day they will read, and goals i.e. using the notetaking strategies they learned about in this chapter.

If You Are Faculty . . .

In Practice

In my English class, I asked students to read an article that detailed the challenges first-generation college students face. Then, they read a non-fiction book written by a woman who was a first-generation college student and they had a writing assignment in which they had to name the challenges the woman faced as she earned her degree. I thought students would recognize immediately what challenges she faced since they had read all about those challenges in the article, so I didn’t prepare them for the assignment.

In my English class, I asked students to read an article that detailed the challenges first-generation college students face. Then, they read a non-fiction book written by a woman who was a first-generation college student and they had a writing assignment in which they had to name the challenges the woman faced as she earned her degree. I thought students would recognize immediately what challenges she faced since they had read all about those challenges in the article, so I didn’t prepare them for the assignment.

However, they struggled until I began to frontload the assignment by saying, “In the next three chapters of this book, you will read about the struggles this first-generation college student faced. We made a list of those challenges when we read the article, so your job is to stop every 10 pages, read the list of challenges and ask yourself, “Did I see any of these challenges in the last ten pages?” Suddenly, students were able to spot them.

Kathryn

- Consider replacing an assignment you currently have with notetaking assignment. For example, if you currently have students answer review questions, ask them to take and submit notes on the chapter instead. As a rule, notes are difficult to grade, but to get around that consider asking students to take notes on a chapter, bring those notes to class and use them during a quiz. Students can evaluate how effective their notes were in helping them answer quiz items and engage in a discussion of how to take better notes. You can also ask students to bring in notes and compare them with each other’s notes.

- Discuss the Warmup, Workout, Cooldown activities with your students and ask to work in small groups to select activities they think best suit the class and the reading they need to do for you. Weigh in as necessary. Create a “group reading plan” based on what students come up with.

- At the beginning of a lecture, show students the textbook features specific to your book. If you have specific suggestions for students about how to use textbook features to better prepare for your class, share them with students. For example, if test items are directly related to chapter outcomes, tell that to students.

- If you assign articles, essays or scholarly articles, rework the resources so they are specific to those readings.

- Do as much work as possible to help students understand why they are reading what you have assigned them to read and help them understand what to “look for.” Faculty often assume it is clear why they have assigned the readings they have since those connections are obvious to the faculty member, but be as explicit as possible.

- When you present content, model how to fill out graphic organizers that “fit” the content you are lecturing over so students can see how graphic organizers work, then suggest they try graphic organizers when they take notes on reading.

Download Chapter 4 Resources

Download chapter 4 resources as a Word doc. Customize them to suit your student’s needs.

Download chapter 4 resources as a Word doc. Customize them to suit your student’s needs.

Click here: Chapter 4-Reading Resources

Media Attributions

- Download

- Task Initiation

- Self-Monitoring

- Metacognition

- Concept Map

- In Practice