27 Indigenous Australians

smoking ceremony, as part of the repatriation of Old People remains.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are the Indigenous peoples of Australia. If one refers to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as a group, it’s best to say either ‘Indigenous Australians’ or ‘Indigenous people’. They are not in fact one group of people, but rather comprise about 500 different tribes in Australia, each with their own language and territory and usually made up of a large number of separate clans. Each of these hundreds of groups have their own distinct set of languages, histories and cultural traditions. And the term Aboriginal is moving out of favor as a descriptive term for the overall native people of the continent, having come from European terminology, and not that of the various tribes involved.

Archaeologists believe that the Indigenous Australian people first came to the Australian continent between 45,000-50,000 years ago. The Indigenous population in Australia is estimated to be about 745,000 individuals or 3 per cent of the total population of 24,220,200. When Europeans settlers first arrived, it is thought that perhaps close to 1.5 million people lived on the continent.

History and Beliefs

Originally the native people of Australia were hunters and gatherers. In addition to this, they had very sophisticated ways of taking care of the land. Through their work with the land they encouraged the growth of specific plants that their preferred animals would eat, using controlled burns, they set up gardens and crops, and they worked with waterways to extend the living space and the breeding of water creatures that were food for them, such as eels. As semi-nomadic people, they moved around with the seasons, returning to more permanent homes in the growing season, and cultivating their crops in season.

First Contact with the Europeans came in 1770:

“On 29 April 1770, HMB Endeavour sailed into Botany Bay, in the country of the Gweagal and Bidjigal peoples of the Dharawal Eora nation, as part of Lieutenant James Cook’s broader exploration of the Pacific.

Approaching the southern shore, his landing party were met by two Gweagal men with spears. Attempts to communicate failed, so Cook’s party forced a landing under gunfire. After one of the men was shot and injured, the Gweagal retreated.

Cook and his men then entered their camp. They took artefacts and left trinkets in exchange. Seven days later, after little further interaction with Gweagal people, the Endeavour’s crew sailed away.”[9]

[From the Journal of James Cook, At Anchor, Botany Bay, New South Wales.]

Sunday, April 29th, 1770.

“In the P.M. wind Southerly and Clear weather, with which we stood into the bay and Anchored under the South shore about 2 miles within the Entrance in 5 fathoms, the South point bearing South-East and the North point East. Saw, as we came in, on both points of the bay, several of the Natives and a few hutts; Men, Women, and Children on the South Shore abreast of the Ship, to which place I went in the Boats in hopes of speaking with them, accompanied by Mr. Banks, Dr. Solander, and Tupia. As we approached the Shore they all made off, except 2 Men, who seem’d resolved to oppose our landing. As soon as I saw this I order’d the boats to lay upon their Oars, in order to speak to them; but this was to little purpose, for neither us nor Tupia could understand one word they said. We then threw them some nails, beads, etc., a shore, which they took up, and seem’d not ill pleased with, in so much that I thought that they beckon’d to us to come ashore; but in this we were mistaken, for as soon as we put the boat in they again came to oppose us, upon which I fir’d a musquet between the 2, which had no other Effect than to make them retire back, where bundles of their darts lay, and one of them took up a stone and threw at us, which caused my firing a Second Musquet, load with small Shott; and altho’ some of the shott struck the man, yet it had no other effect than making him lay hold on a Target. Immediately after this we landed, which we had no sooner done than they throw’d 2 darts at us; this obliged me to fire a third shott, soon after which they both made off, but not in such haste but what we might have taken one; but Mr. Banks being of Opinion that the darts were poisoned, made me cautious how I advanced into the Woods. We found here a few small hutts made of the Bark of Trees, in one of which were 4 or 5 Small Children, with whom we left some strings of beads, etc. A quantity of Darts lay about the Hutts; these we took away with us. 3 Canoes lay upon the beach, the worst I think I ever saw; they were about 12 or 14 feet long, made of one piece of the Bark of a Tree, drawn or tied up at each end, and the middle keept open by means of pieces of Stick by way of Thwarts. After searching for fresh water without success, except a little in a Small hole dug in the Sand, we embarqued, and went over to the North point of the bay, where in coming in we saw several people; but when we landed now there were nobody to be seen. We found here some fresh Water, which came trinkling down and stood in pools among the rocks; but as this was troublesome to come at I sent a party of men ashore in the morning to the place where we first landed to dig holes in the sand, by which means and a Small stream they found fresh Water sufficient to Water the Ship. The String of Beads, etc., we had left with the Children last night were found laying in the Hutts this morning; probably the Natives were afraid to take them away. After breakfast we sent some Empty Casks a shore and a party of Men to cut wood, and I went myself in the Pinnace to sound and explore the Bay, in the doing of which I saw some of the Natives; but they all fled at my Approach. I landed in 2 places, one of which the people had but just left, as there were small fires and fresh Muscles broiling upon them; here likewise lay Vast heaps of the largest Oyster Shells I ever saw.

Monday, April 30, 1770

As Soon as the Wooders and Waterers were come on board to Dinner 10 or 12 of the Natives came to the watering place, and took away their Canoes that lay there, but did not offer to touch any one of our Casks that had been left ashore; and in the afternoon 16 or 18 of them came boldly up to within 100 yards of our people at the watering place, and there made a stand. Mr. Hicks, who was the Officer ashore, did all in his power to intice them to him by offering them presents; but it was to no purpose, all they seem’d to want was for us to be gone. After staying a Short time they went away. They were all Arm’d with Darts and wooden Swords; the darts have each 4 prongs, and pointed with fish bones. Those we have seen seem to be intended more for striking fish than offensive Weapons; neither are they poisoned, as we at first thought. ”

Key Information: Timeline connecting to European arrival in Australia

You will find various links and information to more detailed history of the native and immigrant contacts in this timeline from the Australian National Museum: Education Timeline

As happened in many places around the world, the immigrant Europeans wanted the Indigenous people to conform to the European ideas of community, culture, religion and work. To make this happen, children were taken from their families and introduced into schools, set as farm workers, or adopted out to European families in order to remove the youngest generation from the influence of their tribe, families and clans. This removal of children from their homes took place between 1910-1970. It is thought that something like one in 3 children, especially those with lighter skin color, were taken from their own families and moved into assimilation situations.

After 1970 legislation and policy began to change how Indigenous people were treated. The stories of The Stolen Generation tell us a history of racism and attempted destruction of native cultures, which happened in most continents where colonialism was common.

Example of the story of a person taken from her family: Faye Clayton

The Apology: The National Apology to the Stolen Generations of Indigenous people who were taken from their homes and away from tribes, family and clans.

The expression of spirituality differs between Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders. Aboriginal spirituality mainly derives from the stories of the Dreaming, while Torres Strait Islander spirituality draws upon the stories of the Tagai.

Dreaming:

The mainland native Australian people are storytellers, passing on their culture through a tradition called songlines. Since a songline can span the lands of more than a single language group, different parts of the song are said to be sung in different languages, according to what is happening in the songline. Different languages are not a barrier to the listener, however, because the melodic contour of the song describes the land over which the song passes. A songline has been called a “dreaming track”, as it marks a route across the land or through the sky that is followed by one of the creator-beings or ancestors in the Dreaming.

“The Dreaming has different meanings for different native people. It is a complex network of knowledge, faith and practices that derive from stories of creation, and it dominates all spiritual and physical aspects of life. The Dreaming sets out the structures of society, the rules for social behavior and the ceremonies performed in order to maintain the life of the land.

It governed the way people lived and how they should behave. Those who did not follow the rules were punished.

The Dreaming or Dreamtime is often used to describe the time when the earth and humans and animals were created. The Dreaming is also used by individuals to refer to their own dreaming or their community’s dreaming. In essence, the Dreaming comes from the land. In native society, people did not own the land– it was part of them and it was part of their duty to respect and look after mother earth.”[10]

The Tagai:

“The people throughout the Torres Strait are united by their connection to the Tagai. The Tagai consists of stories which are the cornerstone of Torres Strait Islanders’ spiritual beliefs. These stories focus on the stars and identify Torres Strait Islanders as sea people who share a common way of life. The instructions of the Tagai provide order in the world, ensuring that everything has a place.

One Tagai story depicts the Tagai as a man standing in a canoe. In his left hand, he holds a fishing spear, representing the Southern Cross. In his right hand, he holds a sorbi (a red fruit). In this story, the Tagai and his crew of 12 are preparing for a journey. But before the journey begins, the crew consume all the food and drink they planned to take. So the Tagai strung the crew together in two groups of six and cast them into the sea, where their images became star patterns in the sky. These patterns can be seen in the star constellations of Pleiades and Orion.”[11]

Some substantial assistance in understanding the Tagai comes from this article by Duance Hamacher[12], published through CC licensing from the publication The Conversation:

A Shark in the Stars: Astronomy and Culture in the Torres Straight

Location

The continent of Australia was occupied by people arriving from southeast Asia by boat about 50,000 years ago. These people are considered some of the earliest people to leave Africa for other places.

First contact with the Europeans on James Cook’s ship occurred at Botany Bay, which is a harbor that is now a part of Sydney. The tribes in Australia were thriving at that time, with vibrant communal lifestyles. European settling in Australia started in about 1788, and, as with many colonial situations, brought a mixture of problematic and helpful consequences with their arrival. Because England used the continent as a type of jail for some of its worst criminal offenders, this reality brought additional issues as the British encountered the land and had to find a way to relate to the native inhabitants.

In 1901, however, fewer than 100,000 of the native people remained. It is suggested that three major reasons exist for this societal destruction: disease, losing their resources, and direct killing. European diseases that exposed the population lacking immunological defenses to destruction included smallpox, venereal disease (e.g., gonorrhea), influenza, measles, pneumonia, and tuberculosis. The English settlers and their descendants took over native land and removed the indigenous people by cutting them off from their food resources. There are also clear records of intentional genocidal massacres of native people. There was substantial resistance by the native people, once they realized that the English had decided that the entire continent should belong to them. This resistance was considered barbarous behavior on the part of the Indigenous people, and considered ill considered resistance to the civilizing influence of the English.

England sent over 162,000 convicts in 806 ships between 1788 and 1850 to colonize the Australian continent. Australia as a nation emerged in 1901 as a federation of the six English colonies.

Lifestyle

Indigenous Australians have a rich and complex system of family roles which are at the core of their various cultures. These complex ways of functioning define each person’s place within the community and act as a structure for how people within extended families are bound to one another. Extended family roles define the obligations for each person in the raising and nurturing of the young people. Tradition defines how each individual is meant to support the kinship system. Elders are especially honored, and become a link to the past by passing on their understanding of history, the necessary cultural skills, and oral materials, stories and music to the younger members of the community.

Paintings and carvings on rock, carvings on body ornaments, abstract symbols, including spiral designs, and naturalistic styles are found in centuries of Indigenous art in Australia. Human figures and animals, such as fish, turtles and kangaroos, connected with the hunt or with spiritual beliefs, are common. Modern Indigenous art takes advantage of ancient symbols, including dot painting, animals and figures, and symbols with protected meanings that are shared privately within family structures.

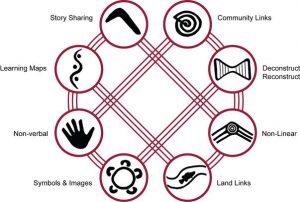

work by Tyson Yungaporta. Yunkaporta, T. (2009)

Aboriginal pedagogies at the culturthal interface

There is a rich oral tradition of myth, relating the ancestral time, ‘The Dreaming’, to the present. A wealth of native symbols are used to present their messages, stories and tradition, and both the ancient and the modern artwork that use the symbols become a way to pass these rich stories on from generation to generation.

“Tribal totem ancestors of Australian Aborigines include the eagle-hawk, kangaroo, and snake. About 40% still follow the traditional hunter-gatherer way of life and live mostly in the remote desert areas of Northern Territory, the north of Western Australia, and in northern Queensland. About 12% of Australia is owned by Aborigines and many live on reserves as well as among the general population; (65% of Aborigines live in cities or towns). Others work on cattle stations, and a few have entered the professions and government service.”[13]

Ritual

There are many reasons for ceremonies in Australian Indigenous society. All have a place in the spiritual beliefs and cultural practices of their communities. These might include transmission of culture and stories, men’s and women’s roles in spiritual practices, and the care of sacred sites.

Example

Indigenous people today continue to meet socially, sharing songs and dances to celebrate daily activities and significant events in their communities.

Participation in ceremonies may be dependent on the age and gender of the people. Children may be involved in some ceremonies while others are restricted to teens and adults. Women’s ceremonies have been protected over time much more than those for men, and photos and images are considered inappropriate for recording these activities.

a ballet written by composer John Antill and based on the real-life

ceremony, at the Empire Theatre, Sydney, in about 1950.

A Corroboree is a ceremonial meeting of Australian Aboriginals, a dance ceremony which may take the form of a sacred ritual or may be more of an informal gathering. The word comes from Dharuk garaabara, denoting a style of dancing.[14]

Another description is “a gathering of Aboriginal Australians interacting with the Dreaming through song and dance”, which may be a sacred ceremony or ritual, or different types of meetings or celebrations.[15]

Looking through various pieces of art, clothing, one can get a feeling for the ritual and drama that is a part of any Corroboree, whether formal ritual or informal gathering.

Creation Story of the Australian Aboriginal people

“Aboriginal Creation Myth.” The Big Myth, 19 June 2020, youtu.be/m8fxRLJJfYU.

International, Survival. “Aboriginal Peoples.” Survival International, 2021, www.survivalinternational.org/tribes/aboriginals.

Cook, James. “Captain Cook’s Journal During the First Voyage Round the World.” Gutenberg Press, 2005, www.gutenberg.org/files/8106/8106-h/8106-h.htm#ch8.

“Australian Museum.” Spirituality – Australian Museum, 1996, web.archive.org/web/20150906190313/australianmuseum.net.au/indigenous-australia-spirituality.

Hamacher , Duane. “A Shark in the Stars: Astronomy and Culture in the Torres Strait.” The Conversation, 30 Aug. 2021, theconversation.com/a-shark-in-the-stars-astronomy-and-culture-in-the-torres-strait-15850.

“Profile of Indigenous Australians.” Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2021, www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/profile-of-indigenous-australians.

National Museum of Australia; address=Lawson Crescent, Acton Peninsula. “National Museum of Australia – Timeline.” National Museum of Australia, National Museum of Australia; c=AU; o=Commonwealth of Australia; Ou=National Museum of Australia, 30 Jan. 2020, www.nma.gov.au/learn/encounters-education/timeline.

Jalata, Asafa. “The Impacts of English Colonial Terrorism and Genocide On Indigenous/Black Australians – ASAFA JALATA, 2013.” SAGE Journals, 2021, journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2158244013499143.

“Who Are the Stolen Generations?” Healing Foundation, 2021, healingfoundation.org.au/resources/who-are-the-stolen-generations/.

Australian Aboriginal art. (1994). In H. E. Read, & N. Stangos (Eds.), The Thames & Hudson Dictionary of Art and Artists (2nd ed.). Thames & Hudson. Credo Reference: http://lscproxy.mnpals.net/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/thaa/australian_aboriginal_art/0?institutionId=6500

Australian aborigine. (2018). In Helicon (Ed.), The Hutchinson unabridged encyclopedia with atlas and weather guide. Helicon. Credo Reference: http://lscproxy.mnpals.net/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/heliconhe/australian_aborigine/0?institutionId=6500

“Aboriginal Ceremonies.” Queensland Curriculum and Assessment Authority, Queensland Studies Authority, Queensland Government, 2021, www.qcaa.qld.edu.au/downloads/approach2/indigenous_res010_0802.pdf.