10

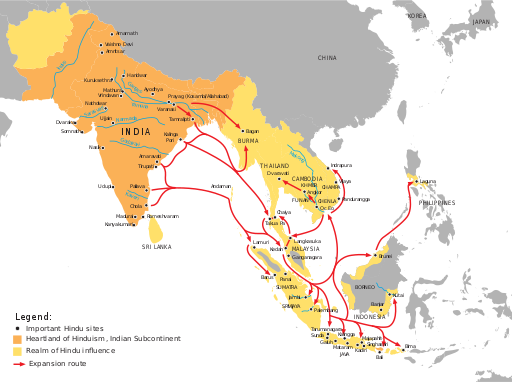

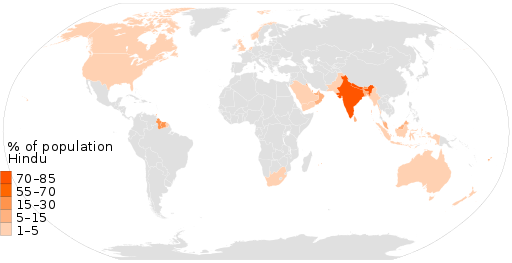

Hinduism is also known as ‘sanatana dharma‘ to Hindus. Considered the oldest organized religion in the world, Hinduism originated in the Indus River Valley about 4,000 years ago in what is now northwest India and Pakistan. With about 1.2 billion followers, about 15% of the world’s population, Hinduism is the third largest of the world’s religions. Hindus believe in a divine power that can manifest as different entities or avatars. Hindu practice has many seemingly independent centers of tradition, often with distinctive sacred texts, deities, myths, rituals, saintly figures, codes of conduct, festivals and so on, but on closer scrutiny these different centers can be seen to link up with each other. This also explains how, while other faiths and civilizations have come and gone, Hinduism continues to thrive and put out new shoots and roots, even when old ones have died away. Diversity is accepted in Hindu traditions, as it considers each path one of value.

The three main incarnations of the divine, called the Trimurti, are Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva. They are considered the deities of creation, preservation and destruction, respectively. They are a part of Brahman–the One Ultimate Reality. Although there are many deities beyond these three, and many images of those deities, in various shrines, temples and holy places, there are no images of Brahman. That One Ultimate Reality is unknowable and beyond human comprehension. But all deities are a part of that One Ultimate Reality. And human goals are to become united with that One–to achieve moksha.

History

Hinduism developed within a group of tribes who referred to themselves as Aryans. There are disputes concerning where they originated; some scholarship says that they were already present in western India, others that they came into the area from Central Asia, or even that they came from further west, including eastern Europe. It is known that the Aryans began to assert their presence in the northwest of the Indian subcontinent at about the beginning of the second millennium BCE, interacting with the Indus civilization that already existed there. The Indus civilization is so named because it seems to have spread out from settlements on the Indus river. They called the Indus river ‘Sindhu’, and it is from this term that ‘Hindu’ comes. Hinduism thus signifies the Aryans’ culture and religious traditions as they developed over time, incorporating elements from other cultures that the Aryans encountered along the way.

The religious tradition that emerged early on (almost before anything that looks like modern Hinduism) had a variety of gods and was centered on priests performing sacrifices using fire and sacred chants. This is much like traditions in many places around the continent.

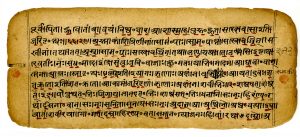

The Indus river valley people create sacred texts, collectively called the Vedas, that contain hymns and rituals from ancient India and are mostly written in Sanskrit. The term Vedas means ‘knowledge’. The Vedas were believed to have arisen from the infallible ‘hearing’ (śruti), by ancient seers, of the sacred deposit of words whose recitation and contemplation bring stability and wellbeing to both the natural and human worlds. The Vedas are believed to have developed over a span of 2000 years. The hymns in particular were largely directed at transcendent powers, most of whom were called devas and devīs (misleadingly translated as ‘gods’ and ‘goddesses’). These powers, individually or in groups, were thought to exercise control over the world through cosmic forces. In this early phase of the Veda, there is reference to a One (ekam) that undergirds all being. During later periods of this earliest pre-Hindu tradition, questioning and changes in spiritual philosophy produced the Upanishads, an addition to the Vedas. These are also written in Sanskrit and contain some of the central philosophical concepts and ideas of the Hinduism we now know. These works record insights into external and internal spiritual reality (Brahman and Atman) that can be directly experienced.

Hindus generally believe in a set of principles called dharma, which refer to one’s duty in the world that corresponds with “right” actions. Hindus also believe in karma, or the notion that spiritual ramifications of one’s actions are balanced cyclically in this life or a future life (reincarnation).

Two other dharma-texts of a different order, the Mahabharata (‘The Great Tale of the Bharatas’) and the Ramayana (‘The Coming of Rama) came later. Both compositions were originally compiled in Sanskrit verse over several hundreds of years, beginning from about the middle of the first millennium BCE. The Mahabharata narrates the story of the rivalry between two groups of cousin warriors, the Pandavas and the Kauravas. With the aid of hundreds of supporting characters and intriguing sub-plots, the story contains teaching about the nature of dharma. Embedded in book 6 of the Mahabharata is perhaps the most famous devotional sacred text of Hinduism, the 700 verse Bhagavad Gita, or ‘Song of (Krishna as) God’. The Gita, as it is often called, mainly contains teachings by Krishna, as Supreme Being, to his friend and disciple Arjuna about how to attain union with him in his divine state.

Painted in South India

The Ramayana recounts the adventures of the exiled king Rama and his various companions as they make their way to the island-kingdom of Lanka – off the southern tip of India – to rescue Rama’s wife Sita, who had been abducted by Ravana, the ten-headed ogre-king of Lanka. For a great many Hindus, the Ramayana, and devotion to the avatar (the chief representation of the Supreme Being in human form) Rama offers an accessible path to salvation.

The mysticism and abstractness of materials in the Vedas is balanced with practical religious elements that form the everyday spirituality of most Hindus. This practical approach described in the Gita states that one should first work to meet one’s social obligations in life. Then the Gita recommends four paths, or yogas, that take into account one’s caste and personality type. The paths of knowledge (jnana), action (karma), devotion (bhakti), or meditation (raja) may be practiced. Other yogas combine elements of these four. Yoga is considered a form of spiritual work in Hinduism.

Key Terms:

Key Terms:

The term Brahman stands for a monistic outlook that sees one invisible and subtle essence or source of all reality—human, divine, and cosmic. All is ultimately one. (Monism is the metaphysical and theological view that all is one, that there are no fundamental divisions between anything, and that a unified set of laws underlie all of nature. The universe, at the deepest level of analysis, is then one thing or composed of one fundamental kind of stuff.) Brahman is the term used to describe “god” as this Oneness of the universe. Supreme Universal Spirit might serve as a better or more broad way to express this concept of Brahman. (do not confuse Brahma from the Trimurti with Brahman. They are completely different!)

Atman is the innermost spirit within all human beings, which ultimately is identical with Brahman. Sometimes we talk about the soul in about the same way. It refers to the real self beyond ego or false self.

Maya reflects a sense of magic and mystery and accounts for the perception of different forms or multiplicity in the world. Maya hides or veils the underlying unity of all things.

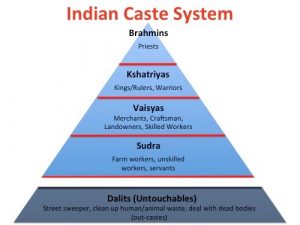

For more than two thousand years in Indian society there has been an organization of the society in the form of the Caste system, although this phrase is a 19th century term. Organization of Indian society had its own structure that, with the coming of the British in the colonial era, took on a much more rigid approach.

For more than two thousand years in Indian society there has been an organization of the society in the form of the Caste system, although this phrase is a 19th century term. Organization of Indian society had its own structure that, with the coming of the British in the colonial era, took on a much more rigid approach.

Varna is a term that literally means type, order, or class and it groups people into classes, a structure that was first used in Vedic times. The four classes were the Brahmins (priestly people), the Kshatriyas (rulers, administrators and warriors), the Vaishyas (artisans, merchants, tradesmen and farmers), and Shudras (laboring classes). It had an additional category, identifying people beyond societal status, considered the untouchables.

Jati is a term used in India to refer to a person’s lineage and kinship group. Indians identify themselves by the community they belong to and these jati are sub-groups of specific castes. The status of the jati one is born into is still a factor in marriage selection, even though the strict isolation of caste in India is softening. Each jati, or subgroup of a caste level, has a set of jobs common to their position, but this can change with effort on the part of the community. Jatis are much less obvious in their caste associations than was previously thought.

The Indian Constitution outlawed the concept of Untouchability in 1947 upon receiving Indian independence from Britain, and the group called Dalit (once considered the untouchables) are working even now towards their civil rights.

The Indian Government has established special quotas in schools and Parliament to aid the lowest jatis. Caste discrimination is not permitted in gaining employment and access to educational and other opportunities. But this does not mean that caste is illegal or has faded away. Caste groups as political pressure groups work very well in a democratic system. Caste may provide psychological support that people seem to need. Economists and political scientists are finding that caste is no real barrier to economic development or political democracy.[1]

Key Takeaway: The Dalit movement in the 20th century

Take some time to read this interview about the Dalits in modern India. Michael Collins is a 2020 Kluge Fellow from the University of Gottingen. Collins is working on a project titled “From Boycotts to Ballots: Democracy and Social Minorities in Modern India.” Boris Granovskiy, who recently detailed at the Kluge Center, interviewed Collins on his work.

The 20th Century Transformation of the Dalit Movement in India

Karma and rebirth/reincarnation are important aspects of the Hindu worldview. Justice is built into the very fabric of reality. The moral consequences of one’s actions will be experienced in this life or the next. So a belief in reincarnation is central to Hindu belief. One moves up or down the caste ladder depending on the caliber of one’s life just lived.

Moksha represents the idea of final liberation or freedom from all limitations, especially the round of death and rebirth. Moksha entails going beyond egoism and identifying with the unity and sacredness that everything shares. After enough lifetimes, and learning achieved, one eventually leaves the cycle of rebirth and is liberated.

There are 4 goals in life:

According to Hinduism, the meaning (purpose) of life is four-fold: to achieve Dharma, Artha, Kama, and Moksha.

The first, dharma, means to act morally and ethically throughout one’s life. However, dharma also has a secondary aspect; since Hindus believe that they are born in debt to the gods and people, dharma calls for Hindus to remember these debts. These include debts to the Gods for various blessings, debts to parents and teachers, debts to guests, debts to other human beings, and debts to all other living beings.

The second meaning of life according to Hinduism is Artha, which refers to the pursuit of wealth and prosperity in one’s life. Importantly, one must stay within the bounds of dharma while pursuing this wealth and prosperity (i.e. one must not step outside moral and ethical grounds in order to do so). So it is considered good to prosper, but not at the expense of others.

The third purpose of a Hindu’s life is to seek Kama. In simple terms, Kama can be defined as obtaining enjoyment from life. Again, this is not to be done at the expense of others, but it is considered a good thing in life to have joy and pleasure.

The fourth and final meaning of life according to Hinduism is Moksha, enlightenment. By far the most difficult meaning of life to achieve, Moksha may take an individual just one lifetime to accomplish (rarely) or it may take several. However, it is considered the most important meaning of life and offers such rewards as liberation from reincarnation, self-realization, enlightenment, or unity with God. Often, in human lives, people focus on this goal as elders. As a young person, the other goals may be more important, or more demanding.

There are stages to human living, too, according to Hinduism:

Ashrama, also spelled asrama, Sanskrit āśrama, in Hinduism, is any of the four stages of life through which a Hindu ideally will pass.

The stages are those of:

(1) the student (Brahamacari), marked by chastity, devotion, and obedience to one’s teacher,

(2) the householder (Grihastha), requiring marriage, the begetting of children, sustaining one’s family and helping support priests and holy men, and fulfillment of duties toward gods and ancestors,

(3) the forest dweller (Vanaprastha), beginning after the birth of grandchildren and consisting of withdrawal from concern with material things, pursuit of solitude, and ascetic and yogic practices, and

(4) the renouncer/ascetic (Sannyasi), involving renouncing all one’s possessions to wander from place to place depending on charity for food, concerned only with union with brahman (the Absolute). Traditionally, moksha (liberation from rebirth) should be pursued only during the last two stages of a person’s life.

Exercise: Flashcards

One fun way to get a handle on difficult or new terms is through flashcards. Try these, just for fun

The Divine

The multiple gods and goddesses of Hinduism are a distinctive feature of the religion. However, Professor Julius Lipner[2] explains that Hinduism cannot be considered polytheistic and discusses the way in which Hindu culture and sacred texts conceptualize the deities, as well as their role in devotional faith. (the full texts, of which this material is only excerpts, can be found at The Hindu Sacred Image and Iconography, Hindu Deities )

“One of the most striking features of Hinduism is the seemingly endless array of images of gods and goddesses, most with animal associates, that inhabit the colorful temples, and wayside shrines and homes of its adherents. Because of this, Hinduism has been called an idolatrous and polytheistic religion.

Hinduism can be likened to an enormous banyan tree extending itself through many centers of belief and practice which can be seen to link up with each other in various ways, like a great network that is one, yet many. The concepts of deity, worship and pilgrimage in Hinduism are a prime example of this ‘polycentric’ phenomenon.

Deities are a key feature of Hindu sacred texts. The Vedic texts describe many so-called gods and goddesses (devas and devīs) who personify various cosmic powers through fire, wind, sun, dawn, darkness, earth and so on. There is no firm evidence that these Vedic deities were worshipped by images; rather, they were summoned through the sacrificial ritual (yajña), with the deity Agni (fire) generally acting as intermediary, to bestow various boons to their supplicants on earth in exchange for homage and the ritual offering. Some Vedic texts speak of a One that seemed to undergird the plurality of these devas and devīs as their support and origin. In time, in the Upanishads, this One (Brahman) was envisaged as either the transcendent, supra-personal source of all change and differentiation in our world which would eventually dissolve back into the One, or as the supreme, personal Lord who was the mainstay and goal of all finite being. In both conceptions, we have the basis for subsequent notions of a transcendent reality that is accessible to humans by meditation and/or prayer and worship.

Exercise: watch this short video about Hindu deities

Avatars

It is in the Bhagavad Gita that we first find sustained textual evidence of developed thinking about devotional faith in a personal God, named Krishna. In this text, Krishna teaches his friend and disciple, Arjuna, about his divine nature and relationship with the world, and how the devoted soul can find liberation (moksha) from the sorrows and limitations of life through loving communion with him. Here, also for the first time in Hinduism, we encounter the doctrine of the avatāra (also known as avatar), which teaches that the Supreme Being descends periodically into the world in embodied form for, according to the Gita, ‘re-establishing dharma, protecting the virtuous and destroying the wicked.’ The doctrine of multiple avatars with their specific objectives was to develop subsequently over the centuries in various sacred texts.

Places of worship

The first archaeological evidence we have of standing temple construction and its implication of image-worship of the deity occurs in about the 3rd century BCE – of a Vishnu temple (in eastern Rajasthan) and of a Shiva temple not too far away. Presumably, since these were constructions of mud, timber, brick, stone etc., the process of temple-building had begun appreciably earlier, though we cannot say exactly where or when. We can also assume from textual and archaeological evidence that image-worship in Hinduism was present by about the 6th to the 5th century BCE.

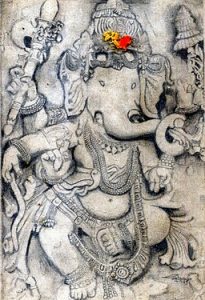

Companions

Most deities have an animal associate (vāhana) which helps identify the deity and express the latter’s specific powers; this was achieved too by an artistic device that attributed multiple body-parts, such as hands and heads, adorned by weapons and other objects, to the image. There are many stories, especially in the Purāṇas, which describe the origin and role of the vāhana and the weapons and other attributes associated with the image.

Worship

Other than by forms of temple worship, which include both personal prayer and various rituals conducted by priests, the deity may be worshipped at home too, in a format called puja. In its simplest form, puja usually consists of making an offering of flowers or fruit to an image of a god at a home shrine. It can also happen by way of meditation (dhyāna). Dhyāna can include highly specialized kinds of visualization of the deity invoked, in which the deity is often envisaged as communicating with the worshipper.

Another form of worshipping the deity in Hinduism is through pilgrimage (yātrā). Pilgrimage is a way of creating a sacred landscape, of indicating that the whole world, including the pilgrim, belongs to the deity and is under its rulership. Through every pilgrimage, Hindus encounter a tīrtha, a sacred ford or crossing-point between heaven and earth, by which they may come to terms with this world of sorrows and arrive at the threshold of liberation. Over time, a great many tīrthas have developed across the Hindu sacred landscape.”

How to look at Hindu mythology

You may be finding the concept of the divine, or dealing with all these deities, really confusing. Try listening to this Ted Talk, which may help:

Bhakti

Dr Rishi Handa[3] looks at bhakti in Hinduism, exploring its common modes, the Hindu concept of enlightenment and how to achieve it, the importance of the Divine Name and the veneration of forms of the deities.

“If any aspect of religiosity can be said to pervade India, it is bhakti. In a land whose culture is filled with a plethora of devīs (goddesses) and devas (gods), it is the foremost way by which Hindus express and experience the Transcendent.

Bhakti is best rendered in English as ‘loving devotion’, but it is much more than that. While common objects of bhakti can be one’s guru (teacher) and one’s country, this bhāva (emotion or feeling) is typically directed to īśvara (the divine, ‘God’). Bhakti can be articulated through gratitude, honoring of the deities, engaging in formal ritual service to a deity, hymn-singing, reading devotional scriptures, and constantly remembering the name of one’s deity. This list is certainly not exhaustive.

The nine modes of bhakti

According to a number of Hindu texts, there are nine ways of expressing bhakti. These differ depending on the text. According to two of the key Purāṇas of Hinduism, the Bhāgavata Purāṇa centred on Krishna (also spelt Kṛṣṇa), and the Viṣṇu Purāṇa (focused on Vishnu, also spelt Viṣṇu), the nine ways are:

- Shravana: Hearing the Lord’s virtues, glories and stories.

- Kīrtana: Singing the Lord’s glories in the form of hymns.

- Smarana: Remembering the Lord at all times.

- Pādasevana: Serving the Lord’s Feet.

- Archanā: Honouring the Lord.

- Vandanā: Prayer and prostration unto the Lord.

- Dāsya bhakti: Being a servant of the Lord.

- Sākhya bhakti: Friendship with the Lord.

- Ātma-nivedana: Self-surrender to the Lord.

A little summary…

You might be feeling a little overwhelmed by all of this detail and history. Try a summary from Crash Course:

“Discovering Sacred Texts: Hinduism.” The British Library, The British Library, 13 Sept. 2019, www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/videos/hinduism.

Lipner, Julius. “Hindu Deities.” The British Library: Discovering Sacred Texts, The British Library, 3 Dec. 2018, www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/articles/hindu-deities#authorBlock1.

Lipner, Julius. “The Hindu Sacred Image and Its Iconography.” The British Library: Discovering Sacred Texts, The British Library, 17 May 2019, www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/articles/the-hindu-sacred-image-and-its-iconography.

Lipner, Julius. British Library, Discovering Sacred Texts, 2019, www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/articles/sacred-texts-in-hinduism.

Breiner, Andrew. “The 20th Century Transformation of the Dalit Movement in India.” The 20th Century Transformation of the Dalit Movement in India | Insights: Scholarly Work at the John W. Kluge Center, 31 July 2020, blogs.loc.gov/kluge/2020/07/the-20th-century-transformation-of-the-dalit-movement-in-india/.

“The Core Tenets of Hinduism.” PBS LearningMedia, GBH, 16 Dec. 2020, illinois.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/sj14-soc-hinduism/the-core-tenets-of-hinduism/#.WiF-ukqnFPY.

Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., www.britannica.com/.

Green, John. “Crash Course Hinduism.” Crash Course, 11 Sept. 2012, youtu.be/0tpVZrsvK-k.

“Indian Pantheons: Crash Course World Mythology #8.” Crash Course, 14 Apr. 2017, youtu.be/V_NJAJGCKD8.

Johnson, Jean, and Donald Johnson. “Jati: The Caste System in India.” Asia Society, 2021, asiasociety.org/education/jati-caste-system-india.

- https://asiasociety.org/education/jati-caste-system-india ↵

- Julius Lipner is Professor Emeritus in Hinduism and the Comparative Study of Religion in the Faculty of Divinity at the University of Cambridge. He specializes in Hindu philosophical theology and modern Hinduism and in the relationship between Hinduism and Christianity. His published works include The Face of Truth: A Study of Meaning and Metaphysics in the Vedāntic Theology of Rāmānuja (1986), Brahmabandhab Upadhyay: The Life and Thought of a Revolutionary (1999), Ānandamath or The Sacred Brotherhood (2005), Hindus: their religious beliefs and practices (2nd ed. 2010), and Hindu Images and their Worship with special reference to Vaişņavism: A Philosophical-Theological inquiry (2017), and numerous journal articles. He is an Emeritus Fellow of Clare Hall, University of Cambridge, and a Fellow of the British Academy. ↵

- Dr Rishi Handa is Head of Sanskrit at St James Senior Boys school. ↵