4

The Daoists, beginning with the supposed founder, Laozi (Lao Tzu), taught about nature and its operation and what it meant to live harmoniously with the Dao. The Dao is said to be the principle or power that makes the universe move through the patterns and rhythms seen in nature. Daoism arose around 500 BCE, during a time when spiritual ideas were developing in both the East and the West. The Daoists saw the trappings of civilization as something artificial or at least far removed from the Dao, the source of all. Disdaining formal education, Daoists advocated a more intuitive path through life best conveyed through stories, or described using images such as the movement of water. Simplicity, gentleness, humility, seeing the relative nature of things, and a certain earthiness were Daoist values. Yet this apparent ordinariness in approaching life also embodied a rather different way of looking at the world and of being in it. Daoists sought a special effortless way of acting to accomplish one’s purposes, which included serenity and longevity.

Key Ideas

You will want to know a few key details about the history and content of Daoism. Take two minutes to watch this Britannica video, Q and A about Daoism.

- Key leaders

- Basic dates

- Key texts

- Definition of Dao

- Life goals

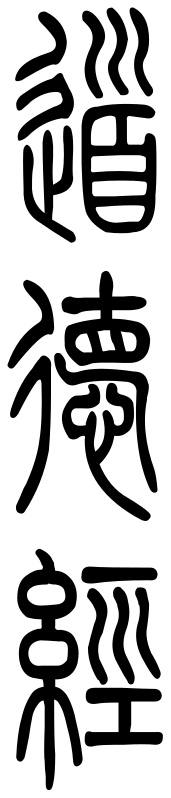

Two texts form the basis of Daoism: the Laozi and the Zhuangzi. The Laozi—also called the Daodejing, or The Way and Its Power—has been understood as a set of instructions for self-cultivation. A number of terms within its teachings are considered key to living within the Dao.

When we look at very approachable translations of the Daodejing and the Zuangzi by Robert Eno[1] of the University of Indiana, we get some excellent narrative from him about this text (and this scholar’s materials have been made available for free for teaching purposes, and are included throughout this chapter):

“Everyone familiar with the field of Chinese thought knows that Daoism sells in America and Confucianism doesn’t. And it’s no wonder. Daoist books are beautifully written, poetic, imaginative, and often playful. And as far as serious thinking goes, Daoist texts sound deeply profound, while Confucians have a tendency to seem shallow and pedantic. One of the great attractions of Daoist texts is actually that the sense of wisdom they convey is so deep that it frequently seems impossible to understand what they mean. But when we hear Laozi utter majestic words such as, “Reaching the ultimate of emptiness, deeply guarding stillness, the things of the world arise together; thereby do I watch their return,” it seems almost sacrilegious to ask precisely what he’s talking about.

While the Confucians were an identifiable school during the Warring States period (450-221 BCE), with teachers and students who shared an identity as disciples of the great Master, Confucius, there was, during the same period, no group of people who called themselves “Daoists” or were labeled by that term. The books we call Daoist are instead independent works, negative reactions against Confucianism that share many features, but whose authors were not necessarily aware of one another or conscious of contributing towards the formation of a school of thought.

We do not know, for example, whether the authors of the Daodejing and Zhuangzi were teachers with students or merely solitary writers whose words were read and passed down by friends and admirers chiefly after their deaths. Only after the Classical period was long over did scholars group these texts into a single school and coin a name for it, calling it the “School of Dao” because of the unique role that the authors of these texts assigned to the term Dao. For these writers, the Dao was not just a teaching that they promoted, in competition with the Daos that other teachers offered.

For Daoists, the term “Dao” referred to a fundamental order of the universe that governed all experience and that was the key to wisdom and human fulfillment.

The origins of Daoism

Daoism appears to have begun as an escapist movement during the early Warring States period, and in some ways it makes sense to see it as an outgrowth of Confucianism and its doctrine of “timeliness.” That doctrine originated with Confucius’s motto: “When the Way prevails in the world, appear; when it does not, hide!” Even in the Confucian Analects, we see signs of a Confucian trend towards absolute withdrawal. The character and comportment of Confucius’s best disciple, Yan Hui, who lived in obscurity in an impoverished lane yet “did not alter his joy,” suggest this early tendency towards eremitism (the “hermit” lifestyle). Righteous hermits were much admired in Classical China, and men who withdrew from society to live in poverty “in the cliffs and caves” paradoxically often enjoyed a type of celebrity status.

The legend of Bo Yi, a hermit who descended from his mountain retreat because of the righteousness of King Wen of Zhou, led to the popular idea of hermits as virtue-barometers — they rose to the mountains when power was in the hands of immoral rulers, but would come back down to society when a sage king finally appeared. Patrician lords very much valued visits from men with reputations as righteous hermits, and this probably created the opportunity for men to appear at court seeking patronage on the basis of their eremitic purity. Possibly during the fourth century, this eremitic tradition seems to have generated a complex of new ideas that included appreciation for the majestic rhythms of the natural world apart from human society, a celebration of the isolated individual whose lonely stance signaled a unique power of enlightenment, and a growing interest in the potential social and political leverage that such renunciation of social and political entanglements seemed to promise. The product that emerged from these trends is the Daodejing of Laozi, perhaps the most famous of all Chinese books. This, along with the Zhuangzi attributed to Chuang Zu (or Zhuangzi) forms the foundation of Daoist thought and teaching.

Key Figures in Daoism

The main Taoist figures were Laozi, or Lao-Tzu (sixth century BCE) and Chuang-Tzu, or Zuangzi (fourth century BCE). They are notable for having characterized the notion of wu wei or non-action, a key element at the center of Daoist thought.

Laozi

Laozi

Despite the fact that after his death he became one of the world’s two or three bestselling authors, Laozi never actually died. In traditional China, many people believed that this was so because Laozi had possessed the secret of immortality and had evaded death by transforming his body into a non-perishable form, after which, being able to fly, he had moved his home to heavenly realms. Modern scholars believe that the reason Laozi never died is because he never lived. There was never any such person as Laozi. “Laozi” means “the Old Master.” Lao is not a Chinese surname and Laozi was clearly never meant to be understood as an identifiable author’s name.

The Daodejing is an anonymous text. Judging by its contents, it was compiled by several very different authors and editors over a period of perhaps a century, reaching its present form perhaps during the third century BCE. However, the authorial voice in the Daodejing is so strong that readers of the text were from the beginning fascinated with the personality of the apparent author, and among the deep thinkers who claimed to understand the book, there were some who also claimed to know all about the man who wrote it. Pieces of biography began to stick to the name Laozi, and, to make sure that readers understood that Laozi was a more authoritative person than Confucius, his biography came to include tales of his personal relationship to Confucius. Laozi, it seemed, had actually lived before Confucius and had actually been Confucius’s teacher. Confucius had journeyed far to study with the great Daoist master, whose wisdom he recognized. Unfortunately, Confucius had not been wise enough to grasp Laozi’s profound message and Laozi, for his part, had found Confucius to be a well-meaning but unintelligent pupil.

Chuang Tzu

Chuang Tzu

More commonly known as Zhuangzi (literally “Master Zhuang”) lived around the 4th century BCE during the Warring States period. He is credited with writing—in part or in whole—a work known by his name, the Zhuangzi.

The only account of the life of Zhuangzi is a brief sketch in chapter 63 of Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian, and most of the information it contains seems to have simply been drawn from anecdotes in the Zhuangzi itself. Sima Qian writes:

-

-

“Chuang-Tze had made himself well acquainted with all the literature of his time, but preferred the views of Lao-Tze; and ranked himself among his followers, so that of the more than ten myriads of characters contained in his published writings the greater part are occupied with metaphorical illustrations of Lao’s doctrines. He made “The Old Fisherman,” “The Robber Chih,” and “The Cutting open Satchels,” to satirize and expose the disciples of Confucius, and clearly exhibit the sentiments of Lao. Such names and characters as “Wei-lei Hsu” and “Khang-sang Tze” are fictitious, and the pieces where they occur are not to be understood as narratives of real events.”

Zhuangzi is traditionally credited as the author of at least part of the work bearing his name, the Zhuangzi. This work, in its current shape consisting of 33 chapters, is traditionally divided into three parts: the first, known as the “Inner Chapters”, consists of the first seven chapters; the second, known as the “Outer Chapters”, consist of the next 15 chapters; the last, known as the “Mixed Chapters”, consist of the remaining 11 chapters. The meaning of these three names is disputed: according to Guo Xiang, the “Inner Chapters” were written by Zhuangzi, the “Outer Chapters” written by his disciples, and the “Mixed Chapters” by other hands; the other interpretation is that the names refer to the origin of the titles of the chapters—the “Inner Chapters” take their titles from phrases inside the chapter, the “Outer Chapters” from the opening words of the chapters, and the “Mixed Chapters” from a mixture of these two sources.

Zhuangzi was renowned for his brilliant wordplay and use of parables to convey messages. His critiques of society and historical figures are humorous and at times ironic.

-

The Daodejing

Much of the attraction of the Daodejing is the product of its very powerful rhetoric. It is written in a uniquely resonant style, and fortunately it is possible to capture some of this resonance even in English translation. The arcane or mysterious style of the Daodejing is not an accident. It seems very clear that the composers of the text wanted the book to be mysterious. Part of the message that the Daodejing is meant to convey is precisely that there is a type of wisdom that is so subtle and esoteric that it is difficult for ordinary minds to comprehend.

Key Point

The opening phrase of the text sets its tone: “A Dao that may be spoken is not the enduring Dao.” What does this say about the book we are about to read? Among other things, that it will not tell us what the Dao is, since this is beyond the power of words to convey.

In the original Chinese, the first line is famously difficult to understand. Since the term that the text chooses to use for the word “spoken” is Dao (which includes “to speak” among its meanings), the first six words of the book include the word Dao three times (more literally it reads: “A Dao you can Dao isn’t the enduring Dao.”) Throughout the Daodejing the very compressed language challenges readers to “break the code” of the text instead of conveying ideas clearly. Every passage seems to deliver this basic message: Real wisdom is so utterly different from what usually passes for wisdom that only a dramatic leap away from our ordinary perspective can allow us to begin to grasp it.

Basic ideas of the Daodejing

The Daodejing is often a vague and inconsistent book and it is sometimes tempting to wonder whether its authors really had any special insight to offer, or whether they just wanted to sound impressive. But the book does in fact articulate ideas of great originality and interest, ideas that have had enormous influence on Asian culture. The following eight points are among those most central to the text:

1. The nature of the Dao. There exists in some sense an overarching order to the cosmos, beyond the power of words to describe. This order, which the book refers to as the Dao, has governed the cosmos from its beginning and continues to pervade every aspect of existence. It may be understood as a process that may be glimpsed in all aspects of the world that have not been distorted by the control of human beings, for there is something about us that runs counter to the Dao, and that makes human life a problem. Human beings possess some flaw that has made our species alone insensitive to the Dao. Ordinary people are ignorant of this fact; the Daodejing tries to awaken them to it.

2. Changing perspective. To understand the nature of human ignorance, it is necessary to undergo a fundamental change in our perspective. To do this, we need to disentangle ourselves from beliefs we live by that have been established through words and experience life directly. Our intellectual lives, permeated with ideas expressed in language, are the chief obstacle to wisdom.

3. Value relativity. If we were able to escape the beliefs we live by and see human life from the perspective of the Dao, we would understand that we normally view the world through a lens of value judgments — we see things as good or bad, desirable or detestable. The cosmos itself possesses none of these characteristics of value. All values are only human conventions that we project onto the world. Good and bad are non-natural distinctions that we need to discard if we are to see the world as it really is.

4. Nature and spontaneity. The marks of human experience are value judgments and planned action. The marks of the Dao are freedom from judgment and spontaneity. The processes of the Dao may be most clearly seen in the action of the non-human world, Nature. Trees and flowers, birds and beasts do not follow a code of ethics and act spontaneously from instinctual responses. The order of Nature is an image of the action of the Dao. To grasp the perspective of the Dao, human beings need to discard judgment and act on their spontaneous impulses. The Daodejing celebrates spontaneous action with two complementary terms, “self-so” and “non-striving” (ziran and wuwei). The inhabitants of the Natural world are “self-so,” they simply are as they are, without any intention to be so. Human beings live by purposive action, planning and striving. To become Dao-like, we need to return to an animal-like responsiveness to simple instincts, and act without plans or effort. This “wuwei” style of behavior is the most central imperative Daoist texts recommend for us.

5. The distortion of mind and language. The source of human deviation from the Dao lies in the way that our species has come to use its unique property, the mind (xin). Rather than allow our minds to serve as a responsive mirror of the world, we have used it to develop language and let our thoughts and perceptions be governed by the categories that language creates, such as value judgments. The mind’s use of language has created false wisdom, and our commitment to this false wisdom has come to blind us to the world as it really is, and to the Dao that orders it. The person who “practices” wuwei quiets the mind and leaves language behind.

6. Selflessness. The greatest barriers to discarding language and our value judgments are our urges for things we believe are desirable and our impulse to obtain these things for ourselves. The selfishness of our ordinary lives makes us devote all our energies to a chase for possessions and pleasures, which leaves us no space for the detached tranquility needed to join the harmonious rhythm of Nature and the Dao. The practice of wu-wei entails a release from pursuits of self-interest and a self-centered standpoint. The line between ourselves as individuals in accord with the Dao and the Dao-governed world at large becomes much less significant for us.

6. Power and sagehood. The person who embraces the spontaneity of wu-wei and

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art states that it’s the Green Goat Immortal and the Chester Beatty Library states that it’s the Blue Goat Immortal

leaves self-interest behind emerges into a new dimension of natural experience, and becomes immune to all the frightening dangers that beset us in ordinary experience. Once weakness, poverty, injury, and early death are no longer concepts we employ in our lives, we discover that such dangers do not really exist. Once we are part of the spontaneous order of Nature, it presents no threat to us and we gain tremendous leverage over it. We have the power of the Dao. This active power is wisdom, and the person who possesses it is a sage.

7. The human influence of the sage. The selfless power of the sage endows him or her with a social prestige that cannot be matched by ordinary people. So magnificent is the presence of the sage that those who come into contact with such a person cannot help but be deeply influenced. As in the case of Confucianism, de (character, virtue, power) has power over other people, who will spontaneously place themselves under the protection of and seek to emulate the sage.

8. The political outcome. As the Daoist sage comes effortlessly to subdue the world, he will necessarily be treated as its king. The rule of such a king will be to discard all human institutions and social patterns that are the product of human intellectual effort and value judgments. The people will be returned to a simple and primitive state close to animal society, and this social environment will itself nurture in the population a stance of wuwei. Ultimately, the world will return to the bliss of ignorance and fulfillment in a stable life of food gathering, food consumption, and procreation, all governed by the seasonal rhythms of Nature and the Dao.

Example: The Daoist Farmer

There was a farmer whose horse ran away. That evening the neighbors gathered to commiserate with him since this was such bad luck. He said, “Maybe.” The next day the horse returned, but brought with it six wild horses, and the neighbors came exclaiming at his good fortune. He said, “Maybe.” And then, the following day, his son tried to saddle and ride one of the wild horses, was thrown, and broke his leg.

Again the neighbors came to offer their sympathy for the misfortune. He said, “Maybe.” The day after that, conscription officers came to the village to seize young men for the army, but because of the broken leg the farmer’s son was rejected. When the neighbors came in to say how fortunately everything had turned out, he said, “Maybe.”

It is not hard to see how a philosophy along these lines could have emerged from a group of hermits who had withdrawn out of social disillusionment. The anti-Confucian elements of the Daodejing should also be easy to identify. The most important metaphors that the text uses to symbolize the Dao and the sage are an uncarved block of wood and an undyed piece of cloth, which contrast clearly with the Confucian celebration of the elaborate ritual patterns institutionalized by legendary sage kings. What is more surprising, however, is that the Daodejing proved to be a very popular text among the ruling class of late Classical China. This was the result of the fact that it seemed to provide a paradoxical path to social and political wealth and power through the act of renouncing interest in wealth and power. “The sage places his person last and it comes first,” the Daodejing tells us. Daoists who arrived at feudal courts in the Classical period found that they could attract the interest of ambitious men by linking their Dao of selflessness to an outcome in accord with the most selfish of ambitions.

One important difference between the ideas of the Daodejing and those of the Confucian writers is that while the Confucians made very clear the practical path that people needed to follow to achieve wisdom – the ritual syllabus of the Confucian Finishing School – the Daodejing is extremely vague when it comes to practical advice.

The following terms are considered key in Daoism, found in the Daodejing:

The following terms are considered key in Daoism, found in the Daodejing:

道 Dao—This term is often translated as “the Way,” but the increasing use of the Chinese term in contemporary English makes it better to leave the term untranslated. In ancient texts, the word Dao actually possesses a wide range of meanings. the word Dao derives its modern meaning of a path or way; from the formula of the dance, the word derives a meaning of “formula,” “method”; from the spoken element of the incantation, the word derives the meaning of “a teaching,” and also serves as a verb “to speak.” All ancient schools of philosophy referred to their teachings as Daos. Confucius and his followers claimed that they were merely transmitting a Dao — the social methods practiced by the sage kings of the past: “the Dao of the former kings.” Texts in the tradition of early thought that came later to be called “Daoist” used the word in a special sense, which is why the Daoist tradition takes its name from this term. Daoists claimed that the cosmos itself followed a certain natural “way” in its spontaneous action. They called this the “Great Dao,” and contrasted it to the Daos of other schools, which were human-created teachings, and which they did not believe merited the name Dao in their special sense.

德 de (character, power, virtue)– In its early uses, de seems to refer to the prestige that well-born and powerful aristocrats possessed as a result of the many gifts they dispensed to loyal followers, family members, and political allies (rather like the prestige associated with a Mafia godfather). Later, the term came to be associated with important attributes of character. Although it can be used to refer to both positive or negative features of person, it usually refers to some form of personal “excellence,” and to say that someone has much de is to praise him. The concrete meaning of this term varies among different schools. Confucians use it most often to refer to a person’s moral dispositions (moral according to Confucians, at any rate), and in this sense, the word is often best rendered as “character” or “virtue.” Daoists, however, speak of de as an attribute of both human and non-human participants in the cosmos, and they often describe it as a type of charismatic power or leverage over the limits of nature that the Daoist sage is able to acquire through self-cultivation. As such, it may be best rendered as “power.” The title of the famous book, Daodejing means “The Classic of the Dao and De,” and in this title, de is best understood as a type of power derived from transcending (going beyond) the limits of the human ethical world.

心) Xin (mind/heart)–In Chinese, a single word was used to refer both to the function of our minds as a cognitive, reasoning organ, and its function as an affective, or emotionally responsive organ. The word, xin, was originally represented in written form by a sketch of the heart. There are really four aspects fused in this term. The mind/heart thinks rationally, feels emotionally, passes value judgments on all objects of thought and feeling, and initiates active responses in line with these judgments. Sometimes, the “unthinking” aspects of people, such as basic desires and instinctual responses, are pictured as part of the mind/heart. However, the Daodejing, typically uses the term xin to denote the cognitive mind and its functions of contemplation, judgment, and so forth, all of which the text views as features that distance human beings from the Dao.

仁 Ren (benevolence)–No term is more important in Confucianism than ren. Prior to the time of Confucius, the term does not seem to have been much used; in the earliest texts the word seems to have meant “manly,” an adjective of high praise in a warrior society. Confucius, however, changed the meaning of the term and gave it great ethical weight, using it to denote a type of all-encompassing virtue which distinguishes the truly ethical person. Confucian texts often pair this term with Righteousness, and it is very common for the two terms together to be used as a general expression for “morality.” Other schools also use the term ren, but they usually employ it either to criticize Confucians, or in a much reduced sense, pointing simply to people who are well-meaning, kind, or benevolent. The Daodejing employs the term in this reduced sense, and tendentiously contrasts it with the amorality of the natural world and those who emulate the Dao.

聖 Sheng (sage)–All of the major schools of ancient Chinese thought, with the possible exception of the Legalists, were essentially prescriptions for human self-perfection. These schools envisioned the outcome of their teachings — the endpoint of their Daos — in terms of different models of human excellence. A variety of terms were used to describe these images of perfection, but the most common was sheng, or shengren 聖人, which we render in English as “sage person” or, more elegantly, “sage.” The original graph includes a picture of an ear and a mouth on top (the bottom part merely indicates the pronunciation, and was sometimes left out), and the early concept of the sage involved the notion of a person who could hear better than ordinary people. The word is closely related to the common word for “to listen” (ting 聽). What did the sage hear? Presumably the Dao.

天 Tian (Heaven)–Tian was the name of a deity of the Zhou people which stood at the top of a supernatural hierarchy of spirits (ghosts, nature spirits, powerful ancestral leaders, Tian). Tian also means “the sky,” and for that reason, it is well translated as “Heaven.” The early graph is an anthropomorphic image (a picture of a deity in terms of human attributes) that shows a human form with an enlarged head. Heaven was an important concept for the early Zhou people; Heaven was viewed as an all-powerful and all-good deity, who took a special interest in protecting the welfare of China. When the Zhou founders overthrew the Shang Dynasty in 1045, they defended their actions by claiming that they were merely receiving the “mandate” of Heaven, who had wished to replace debased Shang rule with a new era of virtue in China. All early philosophers use this term and seem to accept that there existed some high deity that influenced human events. The Mohist school was particularly strident on the importance of believing that Tian was powerfully concerned with human activity. They claimed that the Confucians did not believe Tian existed, although Confucian texts do speak of Tian reverently and with regularity. In fact, Confucian texts also seem to move towards identifying Tian less with a conscious deity and more with the unmotivated regularities of Nature. When Daoist texts speak of Heaven, it is often unclear whether they are referring to a deity, to Nature as a whole, or to their image of the Great Dao.

無為 Wuwei (non-striving)–Wuwei literally means “without [wu] doing [wei].” The initial component, wu, indicates absence or non-existence. As a verb, the second term, wei, means “to do; to make,” and therefore the compound term wuwei is sometimes rendered as “non-action”: an absence of doing. However, in the Daodejing, the term is used to characterize the action of the Dao in its creative role and ongoing transformations, and clearly describes a manner of action, rather than an absence of action. The term wei 為 is both phonetically and graphically cognate to a word generally used pejoratively to mean “fake; phoney”: wei 偽. The third century BCE Confucian thinker Xunzi, however, uses the term wei 偽 in a difference and, for him, very positive sense, meaning that which humans accomplish through planning and effort. In this, Xunzi was challenging Daoist celebration of the processes of the non-human, “Dao-governed” world, which are precisely “without wei 偽”: that is, unplanned and free of any purposive intent. This is probably the best way to understand how wuwei functions in Daoist texts: action that occurs without the agency and intent that is characteristic of behavior governed by the human mind. The Daoist sage has perfected the ability to respond to his environment in this purpose-free way.

自然 Ziran (spontaneous, natural) –Like wuwei, ziran is a compound term; The initial component (zi) means “self; in itself,” and the second term, ran, means “as things are; things being so.” Hence, ziran describes a thing as it is in itself, without regard for forces that may act upon it: spontaneous. The term ultimately came to be used as a noun, meaning “Nature” (the non-human, or noncognition-influenced elements of the world we live in). In the translation here, ziran is rendered flexibly in context. For example: “To be sparse in speech is to be spontaneous (ziran)”; “That the Dao is revered and virtue honored is ordained by no one; it is ever so of itself. (ziran)” ; “Assisting the things of the world to be as they are in themselves (ziran)” . Ziran and wuwei are closely related terms in the Daodejing, since a thing or person that is spontaneous in the manner of its being may be understood to be acting without purpose and effort. In appreciating Daoist thought, it is useful to accommodate the notion that the ideals of ziran and wuwei do not inherently foreclose the notion of exerting purposive effort in the pursuit of a cultivated state of purposeless spontaneity.

While wuwei may be simple in the abstract (just behave more or less like your dog does), in practice there are problems (hey, nobody filled my dish!). The text stresses the concept of nonaction or noninterference with the natural order of things. Dao, usually translated as the Way, is difficult to describe. It has been likened to a path, a river, a balance of nature, as well as a vast void, and is considered the origin of nature. If you spend one hour following the imperative to eliminate value judgments and the desires associated with them, you will discover that without a teacher or model rules to follow, it is difficult to follow the Dao of the Daodejing.

It may also be described as the origin of the forces of yin and yang. Yin, associated with shade, water, and feminine. and yang, associated with light, fire, and male, are the two alternating phases of cosmic energy; their balance brings cosmic harmony. The familiar image of the symbol reflects the intertwined duality of all things in nature, a common theme in Daoism. No quality is independent of its opposite, nor so pure that it does not contain its opposite. These concepts are depicted by the division between the portions, and the smaller circles within the large regions.

It may also be described as the origin of the forces of yin and yang. Yin, associated with shade, water, and feminine. and yang, associated with light, fire, and male, are the two alternating phases of cosmic energy; their balance brings cosmic harmony. The familiar image of the symbol reflects the intertwined duality of all things in nature, a common theme in Daoism. No quality is independent of its opposite, nor so pure that it does not contain its opposite. These concepts are depicted by the division between the portions, and the smaller circles within the large regions.

Another important concept in Daoism is ch’ang, i.e. the property of being constant, enduring, eternal. The central goal of Daoism is the attainment of ch’ang-sheng pussu, i.e. immortality. Philosophical Daoism conceives immortality as spiritual and explains it as enlightenment and oneness with the highest principle, the Dao, or The Way. A person who has attained oneness with the Dao is called chen-jen, i.e. a pure human being.

The Zuangzi

The Zhuangzi was one of the earliest texts to contribute to the philosophy of Daoism. Much of it teaches the reader to embrace a philosophy that disengages from such things as education, fashion, politics and the like, and instead encourages the cultivation of our natural inborn skills. One is taught to live a simple and natural life. This is still considered a full and rich life, but not one tied up in culture or other artificial activity.

The literary style of the Zhuangzi is unique, and the format of the text needs to be understood before reading selections from it. Most of the chapters are a series of brief but rambling essays, which mix together statements that may be true with others that are absurd, and tales about real or imaginary figures. It is never a good idea to assume that when Zhuangzi states something as fact that he believes it to be true, or that he cares whether we believe it or not. He makes up facts all the time. It is also best to assume that every tale told in the Zhuangzi is fictional, that Zhuangzi knew that he had invented it, and that he did not expect anyone to believe his stories. Every tale and story in the Zhuangzi has a philosophical point. Those points are the important elements of Zhuangzi’s book (for philosophers, at any rate; the book is famous as a literary masterpiece too).

Example: a story

To wear out one’s spirit-like powers contriving some view of oneness without understanding that it is all the same is called “three in the morning.” What do I mean by “three in the morning?

” A monkey keeper was handing out nuts. “You get three in the morning and four in the evening,” he said. All the monkeys were furious. “All right,” he said. “You get four in the morning and three in the evening.”

The monkeys were all delighted.

There was no discrepancy between the words and the reality yet contentment and anger

were stirred thereby – it is just thus with assertions of “this is so.” Therefore, the Sage brings all into harmony through assertion and denial but rests it upon the balance of heaven: this is called “walking a double path.”

Zhuangzi’s chief strategy as a writer seems to have been to undermine our ordinary notions of truth and value by claiming a very radical form of fact and value relativity. For Zhuangzi, as for Laozi, all values that humans hold dear — good and bad; beauty and ugliness– are non-natural and do not really exist outside of our very arbitrary prejudices. But Zhuangzi goes farther. He attacks our belief that there are any firm facts in the world. According to Zhuangzi, the cosmos is in itself an undivided whole, a single thing without division of which we are a part. The only true “fact” is the dynamic action of this cosmic system as a whole. Once, in the distant past, human beings saw the world as a whole and themselves as a part of this whole, without any division between themselves and the surrounding context of Nature.

But since the invention of words and language, human beings have come to use language to say things about the world, and this has had the effect of cutting up the world in our eyes. When humans invent a name, suddenly the thing named appears to stand apart from the rest of the world, distinguished by the contours of its name definition. In time, our perception of the world has degenerated from a holistic grasping of it as a single system, to a perception of a space filled with individual items, each having a name. Every time we use language and assert something about the world, we reinforce this erroneous picture of the world. We call this approach “relativism” because Zhuangzi’s basic claim is that what we take to be facts are only facts in relation to our distorted view of the world, and what we take to be good or bad things only appear to have positive and negative value because our mistaken beliefs lead us into arbitrary prejudices.

The dynamic operation of the world-system as a whole is the Dao. The partition of the world into separate things is the outcome of non-natural, human language-based thinking. Zhuangzi believed that what we needed to do was learn how to bypass the illusory divided world that we have come to “see before our eyes,” but which does not exist, and recapture the unitary view of the universe of the Dao. Like Laozi, Zhuangzi does not detail any single practical path that can lead us to achieve so dramatic a change in perspective. But his book is filled with stories of people who seem to have made this shift, and some of these models offer interesting possibilities. One of the most well known of these stories is the tale of Cook Ding, a lowly butcher who has perfected carcass carving to a high art. In the Zhuangzi, Cook Ding describes how the world appears to him when he practices his dance-like butchery:

When I first began cutting up oxen, all I could see was the ox itself. After three

years I no longer saw the whole ox. And now — now I meet it with my spirit and don’t look with my eyes. Perception and understanding have come to a stop and spirit moves where it wants. I go along with the natural makeup, strike in the big hollows, guide the knife through the big openings, and follow things as they are.

Key ideas in the text of the Zhuangzi include:

- Relative magnitudes in time and space: Ordinary human life exists in arbitrary dimensions of size and duration. Why should we believe that the human perspective has any intrinsic validity, and why should we not wonder whether we could experience the world from other standpoints?

- The emptiness of words: Zhuangzi attempts to show not only the arbitrary way that words “slice up” the unity of the cosmos, but also the way our faith in words gradually undermines our sensitivity to lived experience.

- The imperative of self-preservation: the person who learns to dance towards self-preservation in every act, never allowing empty values such as loyalty, righteousness, or ren (the cardinal Confucian virtue of reciprocal moral empathy) to distract him from his main task of evading the dangers of the political world.

- The non-distinction between life and death: Despite his commitment to self-preservation in the context of dangerous times, Zhuangzi claims that the line human beings draw between life and death is a non-natural one, and there is no reason for us to cling to life or fear death. The Dao embraces all as one, and once we come to view who we are only in terms of our participation in the Great Dao, we discard the illusion that somehow participation as a live human being is somehow more important or more desirable than participation as a rotting corpse fertilizing the fields, or in any of the endless forms that we may emerge as thereafter.

Background and History

If you want more detail, you should take the time to read this article on the history of the development of Daoism and Daoist thought from Columbia University. Defining Daoism: a Complex History

- “The Classic on the Way and Its Power (Dao de jing) describes how the original whole, the dao (here meaning the “Way” above all other ways), was broken up: “The Dao gave birth to the One, the One gave birth to the Two, the Two gave birth to the Three, and the Three gave birth to the Ten Thousand Things.”(1) That decline-through-differentiation also offers the model for regaining wholeness. The spirit may be restored by reversing the process of aging, by reverting from multiplicity to the One. By understanding the road or path (the same word, dao, in another sense) that the great Dao followed in its decline, one can return to the root and endure forever.”

- “Daoism has always stressed morality. Whether expressed through specific injunctions against stealing, lying, and taking life, through more abstract discussions of virtue, or through exemplary figures who transgress moral codes, ethics was an important element of Daoist practice.”

Augustin, Birgitta. “Daoism and Daoist Art.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/daoi/hd_daoi.htm (December 2011)

Taoism. (2001). In A. P. Iannone, Dictionary of world philosophy. Routledge. Credo Reference: http://lscproxy.mnpals.net/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/routwp/taoism/0?institutionId=6500

Asia for Educators, Columbia University. “Defining ‘Daoism’: A Complex History.” Living in the Chinese Cosmos | Asia for Educators, afe.easia.columbia.edu/cosmos/ort/daoism.htm.

Coutinho, Steve. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, iep.utm.edu/zhuangzi/. “Zuangzi”

Dao De Jing. Translated by Robert Eno, University of Indiana, 2010 scholarworks.iu.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/2022/23426/Daodejing.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y.

Zhuangzi: The Inner Chapters. Translated by Robert Eno, University of Indiana, 2019, scholarworks.iu.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/2022/23427/Zhuangzi-updated.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y.

Hansen, Chad, “Daoism”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2020/entries/daoism/>.

White, Mark D. “The Wisdom of Wei Wu Wei: Letting Good Things Happen.” Psychology Today, Sussex Publishers, 9 July 2011, www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/maybe-its-just-me/201107/the-wisdom-wei-wu-wei-letting-good-things-happen.

- https://ealc.indiana.edu/people/eno-robert.html ↵