22

God grant that the light of unity may envelope the whole earth, and that the seal, ‘the Kingdom is God’s’, may be stamped upon the brow of all its people.

Bahá’u’lláh

Summary

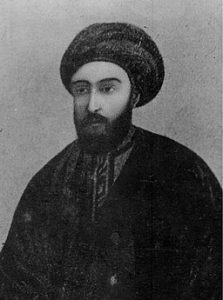

The Baha’i Faith originated in 19th-century Iran as a development from Shi’a Islam. As a new monotheistic global religion it emphasized the ‘oneness’ of God, with different faiths representing different approaches to the one religion. The central figure is Mirza Husayn ‘Ali Nuri (1817–1892), who took the title Baha’u’llah, and whose writings represent the latest revelation of the Word of God. He was preceded by Sayyid ‘Ali Muhammad Shirazi (1819–1850), the Bab (‘Gate’), whom Baha’is regard as having paved the way for Baha’u’llah.

Both the Bab and Baha’u’llah are termed ‘Manifestations of God’, and are viewed as intermediaries between God and humanity. Baha’u’llah was succeeded by his eldest son ‘Abbas Effendi, known as ‘Abdu’l-Baha (1844–1921) and after him by ‘Abdu’l-Baha’s eldest grandson, Shoghi Effendi Rabbani (1897–1957). Today a nine-man body, the Universal House of Justice, first elected in 1963, is the international governing body of the worldwide Baha’i community.

History and Context

With help from Peter Smith[1] and Moojan Momen[2]:

The Baha’i Faith is a dynamic world religion with several million adherents from a variety of different religious and cultural backgrounds. The central figure of the religion is Baha’u’llah, and Baha’is consider him to be the latest in a series of divine messengers. His writings, which promote peace and unity, are at the heart of the Baha’i Faith. He was born into the Iranian nobility but spent the majority of his life living in exile in the Ottoman Empire due to his involvement with the Babi movement, and later his own claims to divine mission.

The Babi movement began in Iran during the 1840s and early 1850s. In 1844, a young Shirazi merchant named Sayyid ‘Ali Muhammad (1819–1850) had announced that he was the intermediary (the ‘bab’ or ‘gate’) between the Shi‘a faithful and the expected messianic figure of the Twelfth Imam, a concept from Shi’a Islam.

The Bab quickly attracted followers (‘Babis’) throughout Iran and the Shi‘a areas of what is now Iraq. He also presented his own book of laws (the Bayān) to replace those of Islam, and announced that he would eventually be followed by the further messianic figure of ‘He whom God would make manifest’.

Mirza Husayn ‘Ali Nuri (1817–1892), who became known as ‘Baha’u’llah’, claimed to be that Twelfth Imam. After a series of religious experiences he wrote a number of major books that provided the Babis with guidance and hope. These works included Hidden Words, Seven Valleys, and Book of Certitude.

Once Baha’u’llah had announced that he was the promised one foretold by the Bab, many Babis accepted him, adopting the name of ‘Baha’is’, i.e. ‘followers of Baha’u’llah’.

The majority of the Báb’s followers accepted Baha’u’llah as the Twelfth Imam and became Bahá’ís by the 1870s. Under Baha’u’llah’s leadership, an emphasis was place on converting of Shi’ite Muslims to Bahá’i. By the 1880s, Iranian Jews, Christians, and Zoroastrians began to convert to being Baha’i. Traveling preachers went to nations surrounding Iran and continued to convert people, the majority converted being Shi’a Muslims.

Baha’u’llah was exiled from Iran in December 1852, after a time in prison after a group of Bábís attempted to assassinate the Shah of Iran. Because of his claims to be the Twelfth Iman, and in some measure due to his growing stature as a religious figure and leader, Baha’u’llah was repeatedly banished. He went from Baghdad to Istanbul to Edirne, a small city in European Turkey, and ultimately, in 1868, to Akka, a

prison city in Palestine. There he lived out the rest of his days either in prison or under house arrest. Except for the years 1868-1870, however, Baha’u’llah was able to receive visitors and had the freedom to write.

Baha’u’llah died in 1892 at the age of 74. His writings throughout his life are considered divine revelations. The followers considered his revelation the ultimate unfolding of all religions.

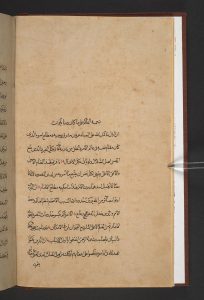

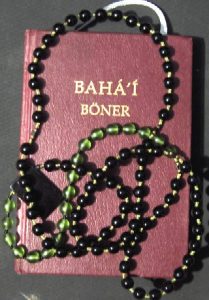

The Tablets

Baha’is refer to the works of Baha’u’llah as being the ‘Revelation’ of the Word of God and to Baha’u’llah’s writings (which comprise of letters to individuals and some books) as ‘Tablets’. Over 20,000 unique works by Baha’u’llah have been identified at the Baha’i World Centre, comprising just under seven million words. The Baha’i Faith is a scriptural religion; the current written texts are considered fully authoritative. Oral reports, although they exist, are considered too unreliable to be fully authoritative and are to be discounted completely if they contradict the written text. Most of Baha’u’llah’s writings are in a mixture of Arabic and Persian, although there are some that are just in Arabic, some in Persian and some in pure Persian (farsi-e sareh, Persian with little or no use of Arabic and other loan words).

As Baha’u’llah spent most of his adult life in exile, remote from the majority of his followers in Iran, his communication with them was mostly through the written word in the form of Tablets, which were often written in response to questions sent by the Baha’is. These would be taken to Iran by a few dedicated couriers and a steady flow of pilgrims who made the arduous journey.

As each Tablet arrived in Iran, it would be studied by its recipient and copies made to distribute to other Baha’is. These Tablets formed the main source of inspiration and guidance for the community, comprising Baha’u’llah’s theological, mystical and ethical teachings and laws for the individual; his social teachings; and teachings intended to bring peace and harmony at the global level.

In Iran, when a Tablet arrived in a town or village, the local Baha’is would gather to hear it read out to them and they would consult about it. Copies of it would be made and many of the Baha’is would have bound compilations of these Tablets either written out by themselves or by a local Baha’i with good handwriting.

The Baha’i scriptures encourage individuals to transform themselves from self-centeredness and a desire for wealth and power into individuals with spiritual attributes such as love, justice, patience, trustworthiness and truthfulness. This transformation best occurs when the individual lives a life of service to others; a cohesive interaction of an individual’s ‘being’ and ‘doing’. The framework for this endeavor are the laws regarding prayer, fasting and meditation given by Baha’u’llah. The aim is to be of service to the wider society, not just the Baha’i community.

These scriptures also give instructions and guidance for the institutional structure of the Baha’i community. They seek to create communities in which power has been removed from individual members of political and religious hierarchies and given instead to elected councils which operate by a consultative decision making process that Baha’u’llah and his successors have developed. The result is the formation of elected councils (the Spiritual Assemblies at the local and national levels) and the establishment in 1963 of the supreme global elected council of the Baha’i community, the Universal House of Justice.

What do Baha’is believe?

Baha’is emphasize the importance of their own authoritative texts in describing Baha’i beliefs and practices. These comprise of the authenticated writings of Baha’u’llah, considered the ‘Word of God’, together with the interpretation of ‘Abdu’l-Baha and Shoghi Effendi and the legislation of the Universal House of Justice. The writings of the Bab are relatively neglected, seen as a source of inspiration, but not binding in terms of practice. A substantial ‘canon’ of authenticated material now exists.

Key Takeaway

“Baha’u’llah’s key theme is world unity. The goal of developing a new world society is a paramount need at the present time. Central to the Baha’i Faith is that all human beings are equally God’s creation regardless of gender, race, nationality or creed and should be respected and treated without prejudice. It is essential to work for the equality of men and women and the emancipation of minority groups. For the world’s peoples and nations to live together in peace, international institutions need to be developed and systems of governance have to promote justice and human wellbeing for all.”

The central principles of the Bahá’í Faith are:

- the oneness of God,

- the oneness of religion, and

- the oneness of humanity.

The purposes of life are to know and worship God and to contribute to the advancement of civilization. The teachings of the Bahá’í offer solutions to problems that have been barriers to the achievement of this unity and to the establishment of peace in the world. Because of their affirmation of the divine origin of all faiths, Bahá’ís are actively involved in interfaith dialogue and understanding.

Human beings have the spiritual capacity to recognize God and to follow his teachings as revealed through his messengers. Evil has no independent existence, such as a figurehead of Satan, but consists of rejecting God’s teachings and allowing oneself to become immersed in selfish desires.

Baha’is believe that the individual soul survives after the death of the body, but the afterlife is beyond our worldly understanding.

Baha’is believe that we have free will, to turn towards God or reject him. They also believe that true religion is compatible with reason, and the Baha’i teachings encourage people to use their intellect in understanding the world (and religion).

The Bahá’í calendar, originating with the Báb ’s ministry in 1844, is a solar calendar divided into nineteen months of nineteen days each with four or five intercalary days to bring the total number of days in the year from 361 to 365 (366 in a leap year). The year begins on the vernal equinox, March 21. The Bahá’í year includes nine holy days, most of which commemorate events in the lives of the Báb and Baha’u’llah, on which Bahá’ís should suspend work. Holy days, like all Bahá’í days, start at sunset and end the following sunset. They are generally celebrated by a worship program followed by refreshments. All holy day observances are open to non-Bahá’ís.

Example of a Baha’i Calendar

From the Montreal Baha’i Community:

Near the end of each year, during the Bahá’í month of ‘Ala or “Loftiness,” which begins at sunset March 1 and ends at sunset, March 20, Bahá’ís observe a period of fasting. The Bahá’í fast involves abstaining from food, drink, and tobacco from sunrise to sunset each day. Exempted from fasting are those under the age of fifteen or over age seventy; women who are pregnant, nursing or menstruating; travelers; the ill; and those performing heavy physical labor. Bahá’ís often gather at restaurants or in each others’ homes to pray and eat before dawn, or to pray and break their fast in the evening. The purpose of the fast is to remember one’s dependency on God and to learn detachment from material things.

Baha’u’llah revealed three obligatory prayers. Bahá’ís are under a spiritual obligation to choose one of these prayers and perform it each day. The Long Obligatory Prayer can be said any time within a twenty-four hour period and is repeated only once. The Medium Obligatory Prayer must be repeated three times in a day, once between dawn and noon, once between noon and sunset, and once between sunset and midnight. The Short Obligatory Prayer is said once a day, between noon and sunset. These Obligatory Prayers are always performed in private.

Example: the texts of the Obligatory Prayers

What are the Manifestations of God?

The Baha’i faith is strictly monotheistic. There is only one God, he is exalted above human understanding, so can only be understood and approached via his prophets and messengers (the ‘Manifestations of God’). All the major world religions originally stem from the teachings of the Manifestations of God and comprise an essential unity. The Manifestations of God include Abraham, Moses, Jesus, Muhammad, Zoroaster, Krishna and the Buddha, and in the contemporary period, the Bab and Baha’u’llah. There will be more Manifestations in the distant future.

Each Manifestation addresses both eternal spiritual truths and the particular needs of his time. These needs change over time, so divine revelation is progressive in nature.

Baha’u’llah’s key theme is world unity. Central to the Baha’i Faith is that all human beings are seen as equally God’s creation regardless of gender, race, nationality or creed and should be respected and treated without prejudice. It is believed that for the world’s peoples and nations to live together in peace, international institutions need to be developed and systems of governance have to promote justice and human wellbeing for all.

Baha’is regard each of the prophet founders of the major religions of the world as being the Manifestations of the Names and Attributes of God (Manifestations of God for short). They have a dual station: in their higher reality, they are essentially one; but in their earthly station, they each come with a unique name and a special mission that is related to the time and circumstances of their coming. This can be likened to the series of teachers that a child has at school. Each teacher builds on what the teacher before has taught and the scriptures of each religion can be likened to the textbook that each teacher brings to the child. So each teacher is equally important to the child and they all have the same station.

However, the series of Divine teachers, the Manifestations of God, has no end. Baha’u’llah teaches that he is not the last one. Whenever humanity needs further guidance, a Manifestation of God will be sent, but Baha’u’llah says that this will not be for at least another one thousand years.

How is the Baha’i community organized?

Those who are formally members of the Baha’i Faith register with its community organization at a local or national level, and are encouraged to become actively involved with its activities. They also become subject to the provisions of Baha’i law. Religious membership is regarded as a matter of individual choice and should never be compelled. Baha’i community life is structured around their own distinctive calendar.

On the first day of each Baha’i month, the Baha’is in a locality meet together for prayers, consultation on community activities, and a social get-together. They also meet to observe the Baha’i holy days commemorating various significant dates in their history as well as their new year celebration at the March equinox (Spring in the northern hemisphere). Additional meetings may be arranged for study of the Baha’i teachings, prayer and community development. Baha’is have a number of holy sites, some of which they perform pilgrimages to, notably at the present time the shrines of Baha’u’llah, the Bab and ‘Abdu’l-Baha, and other places associated with their lives located in the Haifa-Akka area. The Baha’is also have a small number of temples around the world which are used for devotional services and are open to non-Baha’is.

Baha’i law includes both individual obligations (including daily prayer and observing a nineteen-day sunrise-to-sunset fast prior to the Baha’i new year), and social regulations (including obtaining parental consent for marriage and not getting involved in divisive party politics). Observance of individual obligations is regarded as a matter of personal conscience, but the social laws are obligatory. The Baha’i administration comprises both locally and nationally elected councils (‘spiritual assemblies’) responsible for the day-to-day management and direction of Baha’i community affairs, and various ranks of teachers (Counsellors, Board Members), who are appointed for fixed terms to encourage and inspire the Baha’is in their efforts, particularly in promulgating their religion. The Universal House of Justice is presently elected every five years by the members of all the Baha’i national councils.

Regular practices of the Baha’i

The Bahá’í have no clergy, so worship is planned and led by anyone, female or male, young or old. Common elements of worship are the reading or chanting of scripture, music, and prayers. Music that is written to be performed in a worship context usually incorporates passages from the Bahá’í scriptures, and is acapella. Contemporary American Baha’i music now incorporates many genres, including jazz, blues, hip hop and gospel.

Key Takeaway: an example of a Baha’i house of worship

The Bahá’í tradition does not require weekly worship services, but instead a regular gathering known as a Nineteen Day Feast. Generally held on the first evening of each Bahá’í month, or once every nineteen days. It is open only to Bahá’ís.

Another tradition is a Fireside. This is usually an event in a home, where people are invited to come and learn more about Baha’i and to socialize.

Study circles, social activities, education of youth and service are all components of Baha’i life.

The spread and development of the Baha’i Faith

After Baha’u’llah’s death, the Baha’is turned to his eldest son, ‘Abbas Effendi, known as ‘Abdu’l-Baha (1844–1921), and after him to ‘Abdu’l-Baha’s eldest grandson Shoghi Effendi Rabbani (1897–1957). Shoghi Effendi was childless so after a brief ‘inter-regnum’, a nine-man elected body, the Universal House of Justice, was formed in 1963. Referred to repeatedly in the Baha’i writings, the Universal House of Justice remains the Baha’is’ ruling body up to the present-day.

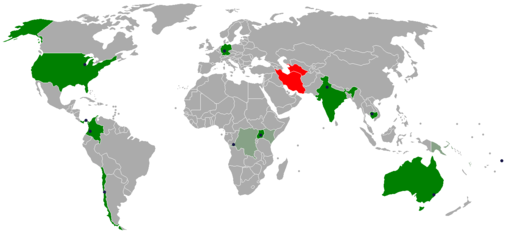

Beginning in the 1890s, the Baha’is began to attract a wider following outside of the are and faith of its origin. Baha’i teachers who settled in North America found a receptive audience for the Baha’i message and a number of active Baha’i groups were established. American Baha’is in turn spread the Baha’i teachings to Europe. These developments were greatly welcomed by ‘Abdu’l-Baha, who wrote extensively to the new Western Baha’is addressing their concerns, and himself made lengthy visits to the West in 1911–1913. In turn, Shoghi Effendi organized campaigns of expansion to the rest of the world, and since the 1950s, an expansion into many parts of sub-Saharan Africa and Asia has occurred. There are now Baha’i communities in almost every country in the world, and Baha’is are drawn from all religious backgrounds and ethnicities.

Bahá’í beliefs and ideas were brought to the United States by immigrants from the Middle East. One of them, Ibrahim George Kheiralla, an Arab Christian from what is today Lebanon, became a Bahá’í in 1889 while living in Egypt. Kheiralla arrived in Chicago in spring of 1894 and was giving classes to interested people in the area. The majority of converts who found the messages and beliefs in universal peace and the oneness of all religion appealing to them were middle- and working-class white Protestant Christians.

American growth of Baha’i was slowed by the World War I and by continued uncertainty about basic Bahá’í teachings. But continuing effort meant that by 1925 the organization of small gatherings had evolved into the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of the United States and Canada. Although the growth rate slowed, and was never very fast, the American Bahá’í community has continued to increase. By 2013 the membership was approximately 171,000. Immigration added to the numbers more than conversion.

From 1975 to 1980 as many as 10,000 Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Laotian Bahá’ís settled in the United States. In the late 1970s and the 1980s they were joined by 10,000-12,000 Iranian Bahá’ís, who fled persecution after Islamic government took power in Iran.

The Bahá’í community has a serious commitment to the abolition of racism, the development of society, and the establishment of world peace. It has increasingly expressed its commitments through a series of core activities devoted to empowering youth of all ages and adults to make changes in their own neighborhoods and villages.

Example of Baha’i thought in current times

Momen, Moojan. “Baha’i Sacred Texts.” British Library, Discovering Sacred Texts: Baha’i, 2019, www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/articles/bahai-sacred-texts.

Momen, Moojan. “Central Figures of the Baha’i Faith.” British Library, Discovering Sacred Texts: Baha’i, 2019, www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/articles/central-figures-of-the-bahai-faith.

“Pandemic Sparks Critical Reflection on Journalism: Bwns.” The Baha’i Faith: Official Website, 2 Oct. 2020, youtu.be/x-dW2WGYGCE.

Smith, Peter. “An Introduction to the Baha’i Faith.” British Library, Discovering Sacred Texts: Baha’i, 2019, www.bl.uk/sacred-texts/articles/an-introduction-to-the-bahai-faith.

“Sydney, Australia: House of Worship.” The Baha’i Faith: Official Website, 20 Aug. 2020, youtu.be/pOrZmnCa418.

“The Three Obligatory Prayers.” The Obligatory Prayers, The Baha’i Faith: Official Website, 2021, www.bahai.org/documents/bahaullah/obligatory-prayers.

“The Tree of Unity: Bahai Short Film.” World Peace Films, 26 June 2020, youtu.be/hypq9-Ih9F0.

Vahman, et al. “Bahá’í.” The Pluralism Project, Harvard University, 12 July 2021, pluralism.org/bahai.

“Baha’i Calendar 178 BE.” Communauté Bahá’íe De Montréal, 2021, www.bahaimontreal.org/en-ca/calendars/baha-i-calendar-176-be.

- Now semi-retired, Associate Professor Peter Smith founded and for many years chaired the Social Science Division at Mahidol University International College, Thailand, where he still teaches courses on the History of Social and Political Thought and on Modern World History. He has published extensively on Baha’i Studies, including An Introduction to the Baha’i Faith (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) and A Concise Encyclopedia of the Baha’i Faith (Oneworld). He holds a PhD in the Sociology of Religion from the University of Lancaster in England. ↵

- Dr. Moojan Momen was born in Iran, but was raised and educated in England, attending the University of Cambridge. He has a special interest in the study of Shi`i Islam, the Baha'i Faith, and more recently the study of the phenomenon of religion. His principal publications in these fields include: Introduction to Shi`i Islam; The Phenomenon of Religion (republished as Understanding Religion); Understanding the Baha’i Faith; and The Baha'i Communities of Iran (1851–1921). He has contributed articles to encyclopaedias such as Encyclopedia Iranica and Encyclopedia of the Modern Islamic World as well as papers to many academic journals. ↵