Chapter 4: Art that Challenges

Two weeks ago, we explored classical art that fits most people’s expectations. One may or may not like Michelangelo, Vermeer, Rembrandt or Caravaggio, but many people feel comfortable with what they are trying to do. But what about uncomfortable art? Have you ever struggled with art that doesn’t match your expectations? Maybe in this class? This week, we will explore more artists who broke the rules to follow their imaginations. Are you up for the encounter?

Challenging art often rebels against classical Convention. Remember that, as we said last night, Classicism often supports and expresses the ethos of elite social castes through strict rules and conventions. But what happens when a classical model encounters resistance?

When we looked at Didactic Art, we viewed Jacques-Louis David’s neo-classical celebration of Napoleon Bonaparte’s imperialist ambitions. His inspiring composition glorifies Napoleon’s 1800 crossing of the St. Bernard Pass between Switzerland and Italy which led to decisive victories over the Austrians. David drenches his painting with Napoleonic gloire, showing the general astride a rising steed, The technique reflects the values of Academic Art.

|

|

| Jacques-Louis David. (1802). Napoleon Crossing Saint Bernhard Pass. | Francisco Goya. (1814). Third of May, 1808. Oil on canvas. |

A dozen years later, the Spanish painter Francisco Goya portrayed a very different aspect of Napoleon’s conquests. Now, Goya was a favored court painter in Madrid. Normally, he used traditional Neo-Classical technique. However, in this revolutionary painting, he captured his people’s resistance to and suffering Napoleon’s invading army. The image commemorates the mass execution of participants in an uprising against French rule. Goya’s horror is reflected in the work’s wholly revolutionary technique. He instinctively blunts the meticulous brushwork and modeling expected of Academic Art and allows the paint to speak for itself. This work is seen by many as a gateway to the modern, anticipating this week’s themes and techniques.

Akhenaten, Unconventional Pharaoh

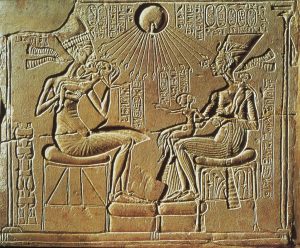

We have mentioned that the Egyptian obedience to a set of conventions remained unchanged for thousands of years. However, in the 14th Century BCE, a highly unconventional king named Akhenaten became Pharaoh. Akhenaten had startlingly new ideas and ideologies, including a reformed religious vision that exalted a Sun God as a nearly monotheistic divinity.

|

|

|

| Pharaoh Akhenaten. (14th C. BCE) Sandstone | Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Solar Disc. (c.1360 B.C) | Nefertiti. (c.1335 BCE). Painted limestone. |

Out of this ideological change grew a remarkable new Amarna style of art. Images of the king are more individuated, even unflattering, depicting a fairly homely man with a thin neck and large nose. The forms within the images are amazingly original: graceful arcs and curves delineating limbs that seem to be in motion. For many people today, the famous bust of Nefertiti, Akhenaten’s wife, is an iconic example of Egyptian art. Yet it is actually very different from the traditional style, an exercise in Amarna elegance that plays well with modern tastes.

All classicisms breed rebellions. Still, many Classical traditions remain resilient. Akhenaten’s ideological, religious, and aesthetic rebellion evaporated at his death as Egypt swung back to old ways.

References

Bust of Queen Nefertiti [Statue]. (ca. 1348-1335 BCE). Berlin, Germany: Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AWSS35953_35953_31676130.

David, J-L. (1800-1801). Napoleon Crossing the Alps: the Great Saint Bernard Pass [Painting]. Versailles, France: Château de Versailles. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AHSC_ORPHANS_1071314149.

Goya, F. (1814). Third of May, 1808 [Painting]. Madrid, Spain: Museo del Prado. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_1039490451.

Pharaoh Akhenaten [Statue]. (14th Century BCE) Cairo: Egyptian Museum. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AWSS35953_35953_31676114.

Stele with Akhenaten, Nefertiti & Daughters Blessed by Solar Disc. [Frieze]. (c.1360 B.C.E.). Berlin, Germany: Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822000133890.

a characteristic feature—subject matter, theme, technique, style—that defines a genre or artistic tradition and is expected and understood by the audience in its context

often contrasted with “romantic” folk traditions, an aesthetic associated with a social elite and a venerated past, especially ancient Greece and Rome. Characterized by clarity, order, balance, symmetry, reason, mathematical precision

art that strives to teach information, instruct behavior, or advocate for an ideology, theology, or morality

an artistic and critical commitment to recovering the values and techniques of classicism, emphasizing reason, mathematical precision, and evoking the classical past. A dominant style in Europe during the 18th and early 19th Centuries

art that follows explicit rules established by a tradition, institution, academy, or school. Sometimes dismissed by the avant-garde art world as overly cautious, derivative, or unoriginal

a style of art that emulates a former classical age, generally emphasizing conventional rules, mathematical precision, and reason over passion.

an innovative, short-lived style of art associated with the unconventional Pharaoh Akhenaten (14th Century BCE). In contrast with the static, formal style of traditional Egyptian art, a look characterized by fluid lines and curves, individualized representation of character, and whimsy

in the Euro-American tradition, a reference to the works, styles, and themes of Greek and Roman antiquity. More generally, an aesthetic valuing clarity, order, balance, unity, symmetry, and dignity, usually honoring a cultural tradition associated with some golden age of the past.