3.1 Renaissance Humanism: Rediscovering Greece

Rinascita, rebirth, Renaissance … rebirth of what? The word Renaissance refers explicitly to a rebirth in knowledge of the Classical Greek tradition which had long been lost. In the 13th Century, Greek learning began to find its way back into Europe.

While Greek learning had been lost in Latin Europe, Arab and Jewish scholars had meticulously preserved them in Arabic translation. Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II[1] cultivated a multi-cultural ethos in Sicily, honoring and emulating Arab culture and scholarship. As Christian kings reconquered lands in Spain held for centuries by Islamic Arabs, Latin scholars began to recover Arab translations of the Greeks, often translated into Latin by Jewish scholars. Greek texts became available to European scholars and wealthy patrons with classical interests.

[1] The title Holy Roman Emperor is misleading. It refers to a more or less fictional grand authority supposedly uniting the kingdoms of Europe into a Christian whole. Early on, these emperors represented Germanic peoples and they generally competed for power with the princes of Italy and France.

Centuries later, this movement was labeled Humanism. Broadly speaking, Humanism may be defined as “any philosophy, or political stance which emphasizes or privileges the welfare of humans and assumes that only humans are capable of reason” (Humanism 2018). The term has been associated with various challenges to conventional values and religion, and today people think of it as a secular opposition to faith. However,

Raphael’s Vatican fresco The School of Athens honors the heroes of Greek learning who so profoundly influenced the Renaissance: Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Archimedes, Epicurus, Pythagoras, Pericles, Plotinus, Euclid, Ptolemy, etc.

|

| Rapahael. (1510). The School of Athens. Fresco. |

The fresco illustrates Renaissance artists’ conscious enthusiasm for Classical tradition and the honor in which Humanistic scholarship was held by the Church: this is the palace of the Pope after all. Inspired and informed by the recovery of Classical learning, Renaissance artists broke from the Byzantine tradition of the medieval Church “in favor of the revival of the culture of ancient Greece and Rome” (Renaissance).

1. The Age of Giotto: A Renewed Way of seeing

Vasari’s three periods of Renaissance art

The age of Giotto: “artists began to imitate nature”

The age of Masaccio (15th Century): a “new understanding of perspective and anatomy

The age of Leonardo, Raphael, and Michelangelo: the “summit of perfection” in mastering and surpassing nature (Giorgio Vasari)

On Giotto

To grasp Giotto’s significance, let’s compare his Pieta with a standard Byzantine Madonna grouping by Giotto’s master, Cimabue.

|

|

| Cimabue. (c. 1290) Madonna and Child, Saint John the Baptist, Saint Peter. Tempera on Panel. | Giotto di Bonine. Pieta (Lamentation of Christ’s Death). (c. 1304). Fresco. |

As we have seen, the Byzantine Icon as practiced by Cimabue was flat, timeless, and placeless, static images of theological ideas. But Giotto’s Pieta roils with the grief of Mary, Jesus’ followers, and angels gathered to honor the divine sacrifice. Indeed, the Genre of the Pieta was innovated around this time as artists like Giotto began to concern themselves with one of the characteristics of Classical art: Pathos–emotion expressed in the figures. In the series of Fresco scenes from the Legend of St. Francis (Assisi, Basilica of St. Francis), Giotto combines Pathos with Rhythmos, dramatizing key moments in the life of the saint.

- Francis renounces his family’s wealth (the corrupting force in the Medieval Church)

- Accompanied by St. Clare, Francis blesses birds, affirming the brotherhood of creation.

|

|

| St. Francis renounces worldly possessions. (c 1300) | St. Francis preaching to the birds. (c. 1300.). |

Each of these frescoes presents a dramatic moment of action located in a particular place. Giotto begins to cultivate the illusion of depth in two-dimensional painting. At this point, the technique is perhaps a bit awkward. It is about to become really sophisticated.

2. Perspective—the Illusion of 3 Dimensions

Vasari’s 2nd stage of the Renaissance era begins with a fusion of art and mathematics. Byzantine art projects very little sense of depth. In Giotto, we see a somewhat clumsy attempt to capture three dimensions in a flat painting. With the recovery of Classical mathematics, the effect of Perspective was about to become far more sophisticated.

The Art of Perspective

The art of depicting solid objects on a two-dimensional or shallow surface so as to give the right impression of their height, width, depth, and position in relation to each other. Only certain cultures have embraced perspective, for example, … ancient Egyptians took no account of spatial recession.

Mathematically-based perspective, ordered round a central vanishing point, was … invented by Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446), described by Leon Battista Alberti (1404–72) in his treatise Della Pittura, and is often referred to as Linear Perspective. … The stage-like organization of pictorial space, in which the composition of a picture is conceived as though viewed through a window, remained a central feature of much western art until the later part of the 19th century (Perspective).

|

|

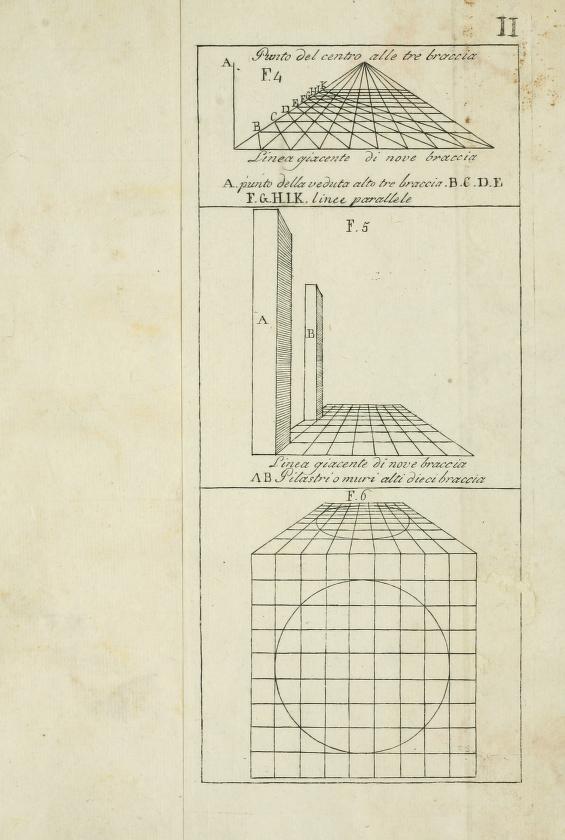

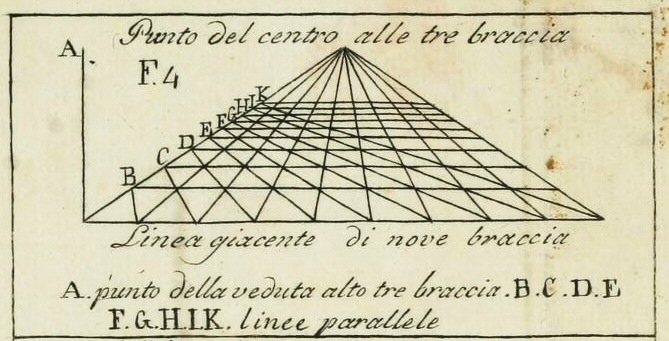

| Diagram of perspective lines and vanishing point | Detail: Vanishing Point |

Page 178 of Alberti’s Della Pittura (1472) provides diagrams that capture the mathematically precise guidelines followed by Renaissance painters in achieving convincing effects of Linear Perspective. Angled lines converge in a distant Vanishing Point “usually located on the horizon, towards which receding lines such as railway tracks appear to converge when depicted or viewed in linear perspective” (Vanishing Point).

References

Cimabue. (c. 1290). Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist and Saint Peter. [Painting]. Washington, D.C.: The National Gallery of Art. Accession Number 1952.5.60. Retrieved from https://library.artstor.org/asset/ANGA_KRESSIG_10312335757.

Dürer, A. (1538). Draughtsman Making a Perspective Drawing of a Reclining Woman. [Woodcut]. Berlin, Germany: State Museum of Berlin. Retrieved from https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/BERLIN_DB_10313750924.

Dürer, A. (2003). [Article]. G. Campbell (Ed.), in The Oxford Dictionary of the Renaissance. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198601753.001.0001/acref-9780198601753-e-1196.

Giotto di Bondini. (ca. 1300.). St. Francis preaching to the birds. Legend of St. Francis. [Fresco]. Assisi, Italy: Basilica of St. Francis. Retrieved from https://www.wikiart.org/en/giotto/st-francis-renounces-all-worldly-goods-1299.

Giotto di Bondini. (ca. 1300.). St. Francis renounces his worldly possessions. Legend of St. Francis. [Fresco]. Assisi, Italy: Basilica of St. Francis. Retrieved from https://www.wikiart.org/en/giotto/st-francis-renounces-all-worldly-goods-1299.

Giotto di Bondini. (ca. 1304). Pieta (Lamentation of Christ’s Crucifixion).[Fresco]. Padua, Italy: Scrovegni Chapel. Retrieved from https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AWSS35953_35953_31692497.

Humanism. (2003). [Article]. In G. Campbell, G. (Ed.s), The Oxford Dictionary of the Renaissance. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198601753.001.0001/acref-9780198601753-e-1889?rskey=wcfuUs&result=8.

Humanism. (2018). [Article]. In I. Buchanan (Ed.), A Dictionary of Critical Theory. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198794790.001.0001/acref-9780198794790-e-331.

Linear perspective. (2009). [Article] In A. M. Colman (Ed.) A Dictionary of Psychology. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100107214.

Perspective. (2010). [Article]. In M. Clarke & D. Clarke (Ed.s). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms. Oxford University Press. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780199569922.001.0001/acref-9780199569922-e-1292.

Renaissance. (2003). [Article]. In G. Campbell, G. (Ed.s), The Oxford Dictionary of the Renaissance. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198601753.001.0001/acref-9780198601753-e-3013.

Vanishing point. (2015). [Article]. Colman, A. [Ed.] A Dictionary of Psychology. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199657681.001.0001/acref-9780199657681-e-8726.

in the Euro-American tradition, a reference to the works, styles, and themes of Greek and Roman antiquity. More generally, an aesthetic valuing clarity, order, balance, unity, symmetry, and dignity, usually honoring a cultural tradition associated with some golden age of the past.

specifically, a 14th Century shift from a narrow, exclusive focus on scripture and Church interests to a broader interest in cultural traditions, especially those of classical Egypt, Greece and Persia. More broadly, a perspective that values and focuses on the capacities of human beings for knowledge, wisdom, and creativity

an era in 15th and 16th century Europe marked by a Renaissance—or rebirth—of interest in and knowledge of classical Greek learning through humanist scholarship that challenged medieval values. In painting and sculpture, the work of artists in Italy, Germany, and the Low Countries which broke with Byzantine conventions to explore the geometry of perception and locate images and actions in time and space

art styled in the manner of Byzantine icons: depictions of Christ, the Virgin Mary, or saints in a stylized manner—flat, emotionless, timeless, placeless, focused on theological dogma. Common Byzantine media: mosaics, frescoes, paint on panel

a conventional theme for paintings and sculptures in the Medieval Catholic Church. A Pieta shows Mary and perhaps other followers grieving over the body of Jesus after his crucifixion.

a Christian image of Jesus, Mary, or the saints which in the Orthodox and Roman Catholic traditions focuses worship and prayer. More specifically, a Byzantine genre of mosaics and paintings with conventional characteristics

a particular type of composition marked by expected, conventional features: e.g. Japanese haiku, Chinese landscape painting, Renaissance sonnet

the Greek term for emotion. In ancient Greek art, the emulation of human emotion and experience within the appearance of human figures.

a painting medium in which pigments are applied to wet, freshly applied plaster, which acts as a binding medium as it dries

in classical Greek art, the illusion of dynamic action in a stationary image through mimetic of a body's patterns of motion during the performance of an action

in visual art, the illusion of 3-dimensional forms and spaces in 2-dimensional compositions, achieved by aligning and scaling forms to suggest depth and distance. Sometimes likened to seeing through a window

the illusion of depth in a 2-dimensional image (e.g. a painting) in which lines angle toward a vanishing point

in visual composition, a distant point at which lines converge, suggesting depth and a horizon. E.g. twin lines of a railroad track converging to create the illusion of distance to the horizon