1.3 Portraiture

All families face the core human challenge: time, decay, and loss. How can art help preserve the image and identity of loved ones? Human figures in ancient art are often funerary. This sarcophagus—i.e. coffin—represents the loving union of a husband and wife.

|

| Sarcophagus of the married couple. (circa 520 BCE). Etruscan culture. Terracotta |

As does funerary art in many cultures, the coffin is topped with an effigy preserving the memory of the deceased. But is it a portrait? The Columbia Encyclopedia’s definition of portraiture emphasizes its role in preserving identity against the corrosive impact of time:

Portraiture is a branch of Representational Art (also known as Figurative Art) which depicts images that can be recognized from the real world. Centuries of post-Renaissance portraiture and nearly two centuries of photography lead many in the Euro-American West to expect Mimetic, imitative realism. A “good” portrait, many feel, would capture the idiosyncrasies of an individual’s appearance and character.

So, what do you think of the representational technique in the Etruscan effigy? How vividly do you see the husband and wife as individuals?

Well, perhaps not so well. Representational Art presents visual subjects that we can recognize. But how? A great deal of world art effectively evokes subjects, not through meticulous imitation of individual features, but through generic ideas. The image of our Etruscan couple makes little attempt to capture the specific look of the individuals. Its features–braided hair, pointed facial features, fixed, dreamy smiles–are Conventional, shared by all the members of the couple’s affluent social class. The Stylized tecnique testifies to a culture in which people wish to be remembered for their status rather than through distinctive profiles.

In the long history of art, Stylized Representation is actually far more pervasive than Mimetic attention to visual detail. In our day, cartoonists and advertisers suggest characters, emotions, and actions with a few deft strokes of a pen. We find these techniques comfortable and convincing because they have become conventional. We “see” in images of Charlie Brown, Lucy, and Linus convincing depictions of child characters whom we know from repeated experience and from narratives that make them live for us. Yet few would argue that Charles’ Schultz’s spare sketch lines meticulously capture the faces of children.[1]

[1] While images from Charles M. Schultz’s Peanuts comic strip are well known around the world, open source images are hard to come by. To sample some of Schultz’s stylized representations of children, try this website: https://www.peanuts.com/.

Most ancient art relied on Stylized features. What conventional, stylized features do you see in these figures from Xochipala Culture figures (Mexico) formed from red-brown micaceous ceramic? What can we plausibly infer about the artistic values motivating these artists from a distant culture?

|

|

|

| Seated shaman and youth. (400 B.C. – A.D. 500). | Female Figure. (circa 15th-10th century BCE). | Tomb of Ch’in Shih-Huang-Ti. (c 246-210 B.C). Standing soldiers and horses. [Terracotta statues]. |

If we define portraiture in terms of the distinctive appearance of the individual, Portraiture was rare in ancient cultures. Yet, Ch’in Shih-Huang-Ti’s famous terracotta army offers an interesting case. In 1974, excavations uncovered the tomb of China’s first emperor. The emperor is guarded by more than 7,500 life size figures, an army of soldiers and horses projecting imperial power into the afterlife. The army was intentionally buried, unknown for 2,300 years.

A close look at the figures seems to suggest that these are portraits of individuals. Each figure has different features: shape of head, beard, expression, facial features. An even closer look, however, shows that the appearance of individuation is misleading. The artists worked with half a dozen distinct templates for each component of a figure’s appearance: head, beard, expression, etc. By mixing and matching these stylized components, the artists achieve hundreds of “individual” figures.

Ancient Chinese and Roman artistic traditions composed individualized portraits of particularly famous heroes. The portrait of Confucius, “one of the great cultural heroes of Chinese history was most likely used in a temple or at an altar dedicated to his system of thought” (explanatory note for the MIA image). Composed long after the sage’s life ended, it displays an artist’s imagined rendering drawing on conventional ideas of the master.

|

|

| Portrait of Confucius. (14th C). Ming dynasty. Ink and colors on silk scroll |

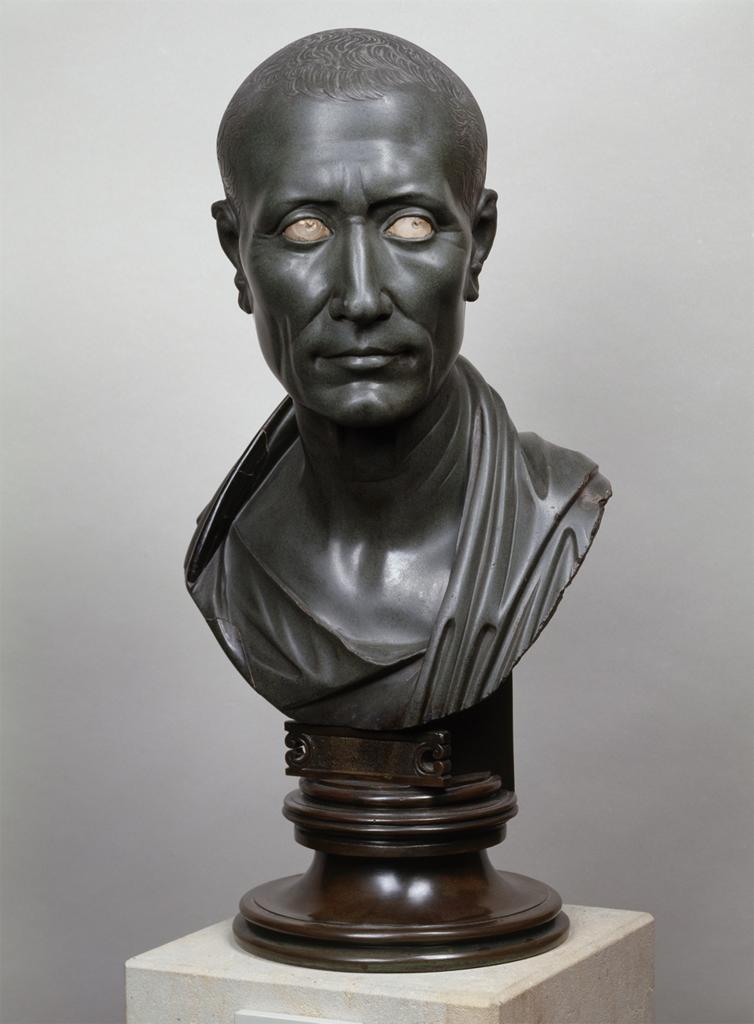

Bust of Julius Caesar. (1st century BCE). Green granite and white glass

|

The bust of Caesar below reflects a more direct knowledge of the emperor’s actual person. Next week, we will explore the emergence of Roman realism out of Classical Greek art. The art which flourished in Rome during the time of the Caesars virtually copied Greek techniques. Does this Mimetic approach seem more “evolved” to us today? Does that response reflect our own cultural orientations?

During the reign of Julius Caesar, Ptolemaic Egypt was absorbed into the Roman Empire. For about 3 centuries, northern Africa, centered in Alexandria, provided the grain which fed the Empire. Roman citizens owned plantations which grew the grain using slave labor. Over this time, the cultures fused, as they tend to do in colonial contexts.

Of course, Egyptian culture is famous for embalming deceased bodies. A mummy was traditionally housed in a sarcophagus with an effigy placed over the face within. These traditional effigies were highly stylized, with little attempt to depict the individual faces of the deceased.

|

|

|

| Coffin of Horankh. (c. 700 BCE). Wood, paint, bronze | Mummies with Child Portraits. (c. 50 CE). | Funerary Portrait. (2nd C.). Encaustic on wood |

During the Roman era in Egypt, the process of mummification was maintained, but the style of the effigies on the coffin changed radically. The deceased began to be remembered in individualized portraits influenced by Roman art traditions. The faces of these two mummified children look at us with a startlingly life-like intensity. (Are they a bit creepy?) The funerary portrait of the young lad would seem to fit into a family’s photo album today.

As we will see next week, the Classical traditions of Greece and Rome that pioneered Mimetic art were cut off by the Byzantine era’s commitment to stylized Christian art. A thousand years later, the concept of the portrait was revived in the Renaissance period. During the Baroque and neo-Classical eras that followed, family portraiture evolved as it became a virtual requirement in elite society. Painters refined their techniques for flattering their patrons’ self-images. In the group composition by Franz Hals, notice the individuated faces and motivations. As the adults sit formally, the youngsters twitch with suppressed energy. Notice, too, the lighting! We’ll have more to say about that next week.

|

|

|

| Franz Hals. (c 1650). Family Group in a Landscape. Oil on canvas. | Joshua Reynolds. (1777). Lady Elizabeth Delmé and her children. Oil on canvas. | John Singer Sargent. (ca. 1892-1893). Lady Agnew. Oil on Canvas. |

Joshua Reynolds was one of the predominant English portrait painters of the 18th Century. Above, he composes Lady Delmé and her children in an intimate grouping. Don’t miss the landscape which is the family’s pride and joy: a great country estate, sign of enormous wealth. But beware of appearances! Lady Delmé might or might not have loved her children, but she would have had little contact with them as they were raised by wet nurses, nannies, and governesses, the “young gentlemen” sent off to public (boarding) school at the age of 5 or 6.

The American painter John Singer Sargent made his name and fortune portraying America’s elite and British nobility. His portrait of the Scottish Lady Agnew illustrates the great skills of portraiture that had developed over 400 years.

Until the 19th Century, the idea of preserving one’s image in a portrait was a privilege reserved only for the extremely wealthy and powerful. Indeed, the whole concept of faithfully recording the appearance of an ordinary person was repugnant to the preference for nobility in art. Yet values began to change in the 19th Century, and we find here Jean-François Millet’s honoring a moment of piety for two humble peasants in France.

|

|

| Jean-FrançoisMillet. (1857-1859). The Angelus. Oil on canvas | Hill & Adamson. (ca. 1845). Jeanie Wilson & Annie Linton, Newhaven Fisherwomen. Salted paper print. |

How many images do you have of your children and grandchildren? Of the children of friends who text you 15 times a day? Well, before the age of the photograph, portraits were almost never available to working people. Only the wealthy and exalted could patronize artists. And then, in the mid-19th Century, the camera came along and brought portraiture to common people. In 1845, Jeanie and Annie Linton could not even imagine having the funds to sit for painted portraits. Yet here they are, captured in a photographic print. Painters now faced competition from a medium affordable to common people and reflective of a growing social awareness of the significance of lives not cushioned by wealth. Artists and writers of the Romantic Era (Week 4) embraced more humble walks of life.

References

Coffin of Horankh. (c. 700 B.C.). Dallas, TX: Dallas Museum of Art. Artstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AMICO_DALLAS_103843037.

Female Figure. [Ceramics]. (circa 15th-10th century BCE). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Artstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/SS7731421_7731421_11046816.

Hals, F. (circa 1650). Family Group in a Landscape. London: National Gallery. Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/frans-hals/family-group-in-a-landscape-2.

Millet, Jean-François. (1857-1859). The Angelus. [Painting]. Paris: Musée d’Orsay. Artstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_10310751251.

Portrait of Confucius. [Painting]. (late 14th century). Minneapolis, MN: Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Artstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AMICO_MINIAPOLIS_103823924.

Portraiture [Article]. (2018). P. Lagasse, & Columbia University, The Columbia Encyclopedia (8th ed.). New York, NY: Columbia University Press. http://ezproxy.bethel.edu/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/topic/portraiture?institutionId=712.

Representational Art [Article]. (2018). Helicon (Ed.), The Hutchinson unabridged encyclopedia with atlas and weather guide. https://ezproxy.bethel.edu/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/heliconhe/representational_art/0?institutionId=712.

Reynolds, Joshua. (1777). Lady Elizabeth Delmé and her children. [Painting]. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art. Artstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ANGAIG_10313967175.

Sarcophagus of the married couple. (c 520 BCE). Paris: Musée du Louvre. Artstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/LESSING_ART_10311441963;prevRouteTS=1602183916331.

Sargent, John Singer. (ca. 1892-1893). Lady Agnew. [Painting]. Edinburgh: National Gallery of Scotland. Artstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AIC_40038.

Seated shaman and youth. [Ceramics]. (400 B.C. – A.D. 500). Artstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/APRINCETONIG_10313684775.

Standing soldiers and horses. [Ceramics]. (ca. 246-210 B.C). China: Tomb of Ch’in Shih-Huang-Ti. Artstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822003053384

Two Mummies with Portraits of Children. (c. 50 CE). Berlin: State Museum of Berlin. Artstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_10311441675.

in visual art, compositions that represent human subjects as individuals, meticulously capturing physical or psychological likenesses

We are about to explore Renaissance traditions in literature. That means reading some poetry. Remember our tips for keeping your head above water reading verse.

- Read aloud, listening for rhythms, patterns.

- Recognize the plain sense of the words before looking for hidden meanings.

- Who talks to whom about what? Clearly seeing this dynamic can open many poems.

- Track themes and patterns of meaning that flow from the above.

The Renaissance also transformed literature. Patrons of the visual arts such as the Medici also patronized scholarship and literature which drew on the newly re-discovered Classical tradition. The great poets of the day emulated Greek epics and absorbed Greek myths. Yet these literary Renaissances looked forward as well as back.

Francesco Petrarch was an Italian scholar, philosopher, and historian. He was also a poet who, along with his contemporary Dante, reached a wide audience by doing something that shocked the scholarly community who wrote everything in Latin. The two poets wrote verse in the contemporary language of Florence, the linguistic ancestor of modern Italian. Petrarch used the Vernacular “for the representation in verse of his personal meditations on love and religion” (Petrarch). Drawing on the Courtly Love tradition, many of the poems in his Il Canzonieri dwell on a woman named Laura whom he admired from afar.

Petrarch. (1368). Sonnet VII, Il Canzonieri [1]

Those eyes, ’neath which my passionate rapture rose,

The arms, hands, feet, the beauty that erewhile

Could my own soul from its own self beguile

And in a separate world of dreams enclose,

The hair’s bright tresses, full of golden glows

And the soft lightning of the angelic smile

That changed this earth to some celestial isle,

Are now but dust, poor dust, that nothing knows.[2]

And yet I live! Myself I grieve and scorn,

Left dark without the light I loved in vain,

Adrift in tempest on a bark forlorn;

Dead is the source of all my amorous strain,

Dry is the channel of my thoughts outworn,

And my sad harp can sound but notes of pain.

[1] Our text of course is translated from the Medieval Italian by T. W. Higginson.

[2] What do we learn in this line? It’s important!

As we did last week, let's use Rhyme Scheme Scan the poems Stanzas. What do you find?

I’ll bet it wasn’t hard for you. We see that the poem is divided into two Stanzas:

But what does that tell us? And do you recognize this pattern?

Well, notice the title. You've heard the word Sonnet, but let's clarify it as a Genre. Following Petrarch, (almost) all sonnets contain 14 lines of verse. In a Petrarchan or Italian Sonnet , the lines aredivided into an Octave (or two Quatrains) and a sestet (Sonnet).

Remember how we said that poetic forms always contribute to the poem’s thematic richness? Let’s follow that lesson and explore the significance of a sonnet’s structure. Start with the poem’s voice: a somber, introspective reflection by an apparently sorrowing individual. The first two stanzas caress in the imagination the beauty of a beloved who is apparently distant, unapproachable. But how? Why? Well let’s look at lines 8 and 9, those that bridge the poem's stanzas:

And yet I live! Myself I grieve and scorn, …

Hmmm. Apparently, the beloved who is adored in the 1st two stanzas is dead, leaving the Persona alone with grief and self-loathing. The poem has made a profound Turn from a problem in the first 8 lines to a resolution, albeit a tragic one, in the final 6. This thematically shifting Turn is a sonnet Convention. In an Italian Sonnet, “the transition from octave to sestet usually coincides with a turn (Italian, volta) in the argument or mood of the poem” (Sonnet).

When reading sonnets, recognizing the Turn injects life into the form. The boundary between the two thematic emphases helps us process its meaning and the decisive shift packs the energy of a change in direction. Don’t miss the Turn in every sonnet!

The Shakespearean Sonnet

The term English Renaissance is reserved for the literature of the Age of Queen Elizabeth (16th-17th Centuries). Several of the poets of the day tried their hand at Petrarch’s form: Michael Drayton, Sir Phillip Sydney, and, of course, Shakespeare. Being the poetic master that he was, Shakespeare decided to make a change to the Italian Sonnet form.

Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer’s Day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate.

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date.

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimmed;

And every fair from fair[3] sometime declines,

By chance, or nature’s changing course, untrimmed;

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st,

Nor shall death brag thou wand’rest in his shade,

When in eternal lines to Time thou grow’st.

So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

[2] For more information on Shakespeare’s poetry, see this summary discussion.

[3] Fair from fair: for Elizabethans, the word fair suggested beauty, health, moral correctness, and a light coloring, especially of skin

OK, let’s see if we can track Shakespeare’s formal scheme. Last week we explored Meter, a pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables. Now, Shakespeare almost always wrote verse in Iambic Pentameter: 5 feet per line, ta-Da-ta-Da-ta-Da-ta-Da-ta-Da. In the audio recording, listen for that subtle interplay between the meter and the normal rhythm of the language.

Shakespeare follows Sonnet Convention in developing a Theme over 14 lines arranged in Stanzas defined by a Rhyme Scheme. As in Petrarch’s sonnets, a Turn shifts the tone and focus of the theme. However, tracking the rhymes, you can see the difference in stanzaic structure. Shakespeare composes a series of three Quatrains followed by a Couplet. And this simple shift makes all the difference. Petrarch placed his thematic Turn in Line 9, leaving a discursive, meandering Sestet to develop his thematic contrast. Shakespeare deferred his Turn until line 13, compressing it into a final couplet that packs the power of a killer punch line.

So OK, how do Theme and Form work together in this Shakespearian Sonnet? The poem’s Persona addresses Thou, obviously a beloved. In the tradition of Courtly Love verse, the poem finds that the beloved’s beauty is superior to that of a summer’s day. Standard stuff, right?

But wait. In a series of comparisons, the poem seems to make an impossible promise. The beloved’s beauty is not only superior today, but it will remain so, apparently eternally. How on earth can the poem promise this? After all, as is lamented in art throughout time, human beauty decays and perishes. Let's consider that killer couplet:

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

This poet offers the beloved something unique: a form of immortality. Her physical beauty may fade as she succumbs to mortality. But its fame will live on forever in the poem that commemorates it. Arrogant? Perhaps. But in Shakespeare’s case, no idle boast. The sonnet has lasted, now, over four centuries.

Shakespeare’s English Sonnet form uses structural imbalance to multiply the power of its thematic Turn: twelve lines over and against two lines with the impact of a punchline. The compression of that stinger Couplet packs more punch than the leisurely reflection of a final sestet in an Italian Sonnet.

Figures of Speech and the Sonnet Tradition

In English poetry, the sonnet has proven to be flexible and tenacious. Many great poets have composed sonnets: Milton (17th Century), 19th Century Romantics—Wordsworth, Shelley, Keats—, 20th Century innovators like e. e. cummings. Let’s sample three very different sonneteers. As we approach these poems, let’s explore some dimensions of rhetorical impact:

Figurative language

Figure of Speech: a form of expression in which language departs from conventional norms for maximum rhetorical effect:

- Figures of Scheme: a figurative pattern of expression that deviates from conventional arrangements of sound and sense through repetition or contrast

- Trope: a figure of speech that plays on meaning so that the implied message differs from the ordinary sense of the expression

Note: popular usage today uses the term trope to refer to a common expression or theme. Traditionally, the term refers to figures of speech that play with and alter the meaning of language.

Analysts count scores of rhetorical figures. Let's look at three Tropes that are central to reading poetry.

3 Poetic Tropes

- Simile: a trope that explicitly compares a “literal” with a “figurative” term, usually indicating the comparison with like or as: e.g. “I wandered lonely as a cloud” (William Wordsworth, “Daffodils,” 1807)

- Metaphor: a trope in which language denotes a “non-literal” thing, idea, or action to characterize a “real” term. E.g. “All the world's a stage, and all the men and women merely players” (William Shakespeare, As You Like It, 1599).

- Paradox: a trope in which two terms in a statement seem contradictory but suggest an elusive point: e.g.: “the child is father of the man (William Wordsworth, “My Heart Leaps Up, 1802)

John Donne

|

| Oliver, Isaac. (before 1622). Portrait of John Donne. |

John Donne (1572–1631) was a widely travelled courtier and diplomat for Queen Elizabeth who composed knotty, sometimes amorous verse. At 49, he became a Dean of London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral, composing devotions on mortality and religious verses called Holy Sonnets. For a century or so, Donne has been a favorite with literature teachers for thorny, hard-to-follow verse that can drive students batty. (For more information on John Donne, explore Hester’s note) Indeed, Dr. Samuel Johnson, the great 18th Century critic, complained about metaphysical poets (Dr. Johnson’s term) like Donne:

The most heterogeneous ideas are yoked by violence together; nature and art are ransacked for illustrations, comparisons, and allusions; their learning instructs, and their subtilty[4] surprises; but … though [readers] sometimes admire, they are seldom pleased (Johnson).

[4] Subtilty: 18th Century spelling of subtlety.

So, have I scared you off? You’re brave, right? Let’s tackle one of Donne’s thorniest Holy Sonnets. Maybe this reading will help:

John Donne, Holly Sonnet, #10.

Batter my heart, three-person'd God, for you

As yet but knock, breathe, shine, and seek to mend;[5]

That I may rise and stand, o'erthrow me, and bend

Your force to break, blow, burn, and make me new.

I, like an usurp'd[6] town to another due,

Labor to admit you, but oh, to no end;

Reason, your viceroy[7] in me, me should defend,

But is captiv'd, and proves weak or untrue.

Yet dearly I love you, and would be lov'd fain,[8]

But am betroth'd unto your enemy;

Divorce me, untie or break that knot again,

Take me to you, imprison me, for I,

Except you enthrall[9] me, never shall be free,

Nor ever chaste, except you ravish[10] me.

[5] But knock: Compare Revelation 3.20, Here I am! I stand at the door and knock. If anyone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in and eat with that person, and they with me.

[6] Usurp’d: i.e. usurped, another way of saying a city under siege by an enemy.

[7] Viceroy: a governor ruling on behalf of a king

[8] Fain: i.e. gladly willing

[9] Enthrall: i.e. enslaved

[10] Ravished: in this case, raped

Try reading the sonnet aloud, listening for the rhythms and the rhyme scheme. Which is this: an Italian Sonnet or a Shakespearian Sonnet? I’ll bet you can tell!

Now, the footnotes point up the difference in diction separating us from the Age of Elizabeth. Still, even with the glosses provided, can we make sense of this challenging text? Before looking for secret codes, start on a small scale. Who is talking to whom? About what?

“Batter my heart, three-person'd God”—clearly, the poem’s voice directly addresses the Trinity—the Christian God in three persons. The sonnet is a prayer. But what sort of prayer with such harsh images of destruction? The difficulty of the verse matches the daunting challenge that Christians have faced through the ages, articulated by the Apostle Paul:

Donne gives anguished voice to the great challenge of repentance: how does a person of faith break the habits of sin and rebellion and learn to obey God’s will? Donne captures the apparent impossibility of it all in a series of metaphors and paradoxes.

- Stanza 1: God’s quiet invitations to faith seem inadequate to a sinner who feels he must be destroyed to find new life.

- Stanza 2: the poet invokes the metaphor of a walled city laboring to admit the besieging God but remaining captive to sin.

- Stanza 3: the metaphor is that of a would-be lover who must break the bonds of marriage to an evil spouse pleading with God to set him free by imprisoning him.

- Final Couplet: a burning paradox—one can only be free by being enslaved to God, chaste by being “ravished.”

These metaphors and paradoxes open the sonnet and a new perspective on Romans 7. Remember: poetry uses everyday figures of speech. It just uses them more creatively!

Gerard Manly Hopkins: God's Elusive Grandeur

| Gerard Manley Hopkins. (1918). Photograph |

An Anglo-Catholic priest, Gerard Manley Hopkins felt that, as a sacrament, he should stop writing poetry. Then, in 1875, five German nuns perished aboard a sinking passenger ship, Hopkins commemorated their faith in The Wreck of the Deutschland and the poetic floodgates opened, often in sonnets.

Gerard Manley Hopkins. (1877) God’s Grandeur

The world is charged with the grandeur of God.

It will flame out, like shining from shook foil;

It gathers to a greatness, like the ooze of oil

Crushed. Why do men then now not reck his rod?[11]

Generations have trod, have trod, have trod;

And all is seared with trade;[12] bleared, smeared with toil;

And wears man's smudge and shares man's smell: the soil

Is bare now, nor can foot feel, being shod.

And for all this,[13] nature is never spent;[14]

There lives the dearest freshness deep down things;

And though the last lights off the black West went

Oh, morning, at the brown brink eastward, springs —

Because the Holy Ghost over the bent

World broods[15] with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.

[11] Reck his rod: that is recognize God’s rod of authority

[12] Trade: in Victorian society, trade was the engine of economic growth, but it was nevertheless despised as a sign of social inferiority. The aristocrat and the gentleman or woman had independent means and did not dirty their hands with trade.

[13] For all this: the word for in this case means despite—even though all this is true …

[14] Spent: i.e. depleted

[15] Broods: i.e. sitting protectively over unhatched eggs, as does a mother hen

The world is charged with the grandeur of God. This is Hopkins’ great theme, one easy to misread. Hopkins never writes of God’s grandeur as a glaring coat of enamel. The word “charged” should be read as elusive potentiality, a compressed, unreleased electrical force.

The first Stanza in this Sonnet poses a problem: why do men not recognize God’s glory? The striking images suggest that divine splendor only rarely emerges from hidden places. Light suddenly flashes from shaken foil. The iridescence of oil flashes only as it gathers “to a greatness” before dropping. One must have faithful eyes to catch these glimpses, and Stanza 2 laments the life conditions that blunt our spiritual sensitivity: the trudging, tiresome routine of life, labor and commercial trade. We can’t even feel the soil through the shoes we wear.

In Stanza 3, the Sestet, the sonnet's Turn leads to redemption. Deep down in all things lies a “dearest freshness” connecting us to spirit. Dawn brings new life following darkness and over all lies the warm, loving protection of the Holy Ghost, the third divine member of the Christian Trinity.

Hopkins always experimented boldly with unusual metrical rhythms. Read the poem aloud or listen to the audio. Feel the force of stressed syllables. A Spondee is a foot in which both syllables are stressed: shook foil; bleared, smeared; foot feel; brown brink, world broods, warm breast, bright wings. Each spondee slows the verse and confers weight on themes.

Claude McKay

|

| Claude McKay. (N.D.) Photographic Portrait. |

Born in Jamaica, Claude McKay emigrated to Harlem and became associated with the Harlem Renaissance. As a poet, he composed in highly traditional verse forms, often the sonnet. However, unlike other writers within that movement, McKay made little effort to adopt a sophisticated cool. He raged in a full-throated roar while retaining a poet’s sense of the complexity of things.

Claude McKay (1921). “America”

Although she feeds me bread of bitterness,

And sinks into my throat her tiger’s tooth,

Stealing my breath of life, I will confess

I love this cultured hell that tests my youth.

Her vigor flows like tides into my blood,

Giving me strength erect against her hate,

Her bigness sweeps my being like a flood.

Yet, as a rebel fronts a king in state,

I stand within her walls with not a shred

Of terror, malice, not a word of jeer.

Darkly I gaze into the days ahead,

And see her might and granite wonders there,

Beneath the touch of Time’s unerring hand,

Like priceless treasures sinking in the sand.

What do you think? Do you find this easier reading? How does McKay use figurative language and the structure of a Shakespearean sonnet to rage against the social forms that bind his people? How does he use numerous Metaphors to process his ambiguous relationship to the "cultured hell” which he also loves? How does he see America's future?

References

Donne, J. Poem #74. In Holy Sonnets. (1633). https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44106/holy-sonnets-batter-my-heart-three-persond-god.

Hester, M. T. (2006). Donne, John. In D. S. Kaslan, D. S. (Ed.), The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature. Oxford University Press. https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780195169218.001.0001/acref-9780195169218-e-0141?rskey=lSIn2y&result=7.

Hopkins, Gerard Manley. (1877). “The Caged Skylark.” https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44391/the-caged-skylark.

Irony. (2015). [Article]. In C. Baldick (Ed.) The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms. Oxford University Press. https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198715443.001.0001/acref-9780198715443-e-615?rskey=Dq616h&result=9

Johnson, S. (1779). Excerpt from “Preface to Abraham Cowley.” https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69382/from-lives-of-the-poets.

Oliver, I. (before 1622). Portrait of John Donne. London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 1849. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:John_Donne_by_Isaac_Oliver.jpg.

Petrarch, F. (1368). Sonnet VII T. W. Higginson [Trans.]. In T. W. Higginson (Ed.) Fifteen Sonnets of Petrarch. New York: Houghton Mifflin & Company, 1903. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/50307/50307-h/50307-h.htm.

Petrarch. (c. 1420-1430). Il Canzoniere. Folio #: fol. 001r. [Manuscript Illustration]. Oxford, UK: Bodleian Library. https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/BODLEIAN_10310369599.

Picone, M. (2002). Petrarch, Francesco. In P. Hainsworth & D. Robey (Ed.s), The Oxford Companion to Italian Literature. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198183327.001.0001/acref-9780198183327-e-2435.

Saville, J. (2006). Hopkins, Gerard Manley. In D. D. Kastan (Ed.) The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature. Oxford University Press. https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780195169218.001.0001/acref-9780195169218-e-0225?rskey=8BCH16&result=1.

in visual art, the quality of imitating as closely as possible the appearance of nature, “the real thing." Often contrasted with stylized technique

in visual art, a representational technique that depicts visual subjects through simplified, exaggerated, or conventional forms rather than through meticulous mimesis

a function of visual art which seeks to depict a visual subject that viewers will recognize from a theoretical “real world.” Opposite: abstract or non-figurative art

in the Euro-American tradition, a reference to the works, styles, and themes of Greek and Roman antiquity. More generally, an aesthetic valuing clarity, order, balance, unity, symmetry, and dignity, usually honoring a cultural tradition associated with some golden age of the past.

an era in 15th and 16th century Europe marked by a Renaissance—or rebirth—of interest in and knowledge of classical Greek learning through humanist scholarship that challenged medieval values. In painting and sculpture, the work of artists in Italy, Germany, and the Low Countries which broke with Byzantine conventions to explore the geometry of perception and locate images and actions in time and space

the 17th Century artistic tradition that followed the Renaissance, characterized by dramatic action, intense passions, chiaroscuro, and gritty social realism. More broadly, any art emulating the values of the Baroque

a style of art that emulates a former classical age, generally emphasizing conventional rules, mathematical precision, and reason over passion.

a late 18th and 19th Century reaction against neo-classical reason which sought to liberate the individual human imagination and embrace its passions, dreams, and irrational visions as sources of wisdom