5.2 Opening to the Sublime

|

| Beaumont, Sir George Howland. (1806). Peele Castle in a Storm. Oil on canvas. |

One day in 1807, William Wordsworth stood before a painting of Peele Castle on the Isle of Man. He realized that he had been there:

from William Wordsworth, Elegiac Stanzas (1807)

I was thy neighbor once, thou rugged Pile!

Four summer weeks I dwelt in sight of thee:

I saw thee every day; and all the while

Thy Form was sleeping on a glassy sea.

Out of this encounter, Wordsworth composed “Elegiac Stanzas” (1807). He contrasts the peaceful conditions of his visit with the tempest depicted by the painter and wonders how he, an artist in a different medium, would have rendered the scene:

Ah! then, if mine had been the Painter’s hand,

To express what then I saw; and add the gleam,

The light that never was, on sea or land,

The consecration, and the Poet’s dream;

I would have planted thee, thou hoary Pile

Amid a world how different from this!

Beside a sea that could not cease to smile;

On tranquil land, beneath a sky of bliss.

The light that never was, on sea or land. For two centuries now, this line has resonated with artists cycling between two tasks: depicting our world and injecting an inner light of the imagination. Wordsworth’s reflection contrasts not only the visions of painter and poet, but also the times of his life. He realizes that with age his vision has grown wiser and darker:

Such, in the fond illusion of my heart,

Such Picture would I at that time have made:

And seen the soul of truth in every part,

A steadfast peace that might not be betrayed.

So once it would have been,—’tis so no more;

I have submitted to a new control:

A power is gone, which nothing can restore;

A deep distress hath humanized my Soul.

Not for a moment could I now behold

A smiling sea, and be what I have been:

The feeling of my loss will ne’er be old;

This, which I know, I speak with mind serene.

So Wordsworth returns to Beaumont’s vision of Peele Castle under very different conditions: “This sea in anger, and that dismal shore.”

O ’tis a passionate Work!—yet wise and well,

Well chosen is the spirit that is here;

That Hulk which labors in the deadly swell,

This rueful sky, this pageantry of fear!

And this huge Castle, standing here sublime,

I love to see the look with which it braves,

Cased in the unfeeling armor of old time,

The lightning, the fierce wind, the trampling waves.

Standing here Sublime: here Wordsworth invokes a very old word that was returning to prominence in the Romantic age. In 1757, philosopher Edmund Burke published a treatise contrasting what he saw as distinct aesthetic responses: the sublime and the beautiful. Contrasting his memory of the castle with the power of Beaumont’s painting, Wordsworth experiences a sublime vision: a ruined castle clinging to a rock, beset by turbulence of wind and sea. This is the sublime:

An experience of the sublime characteristically begins with the interposition of an overwhelming force, which shatters equanimity and produces a feeling of blockage. As this power takes hold of mind and emotions, inertia becomes transport: we are hurried on as if “by an irresistible force.” As the experience recedes, it leaves behind a newly invigorated sense of identity and, frequently, admiration for the blocking power (Sublime).

A key component in the Sublime is danger, for example heights that project a vision out into infinity. Some people seek sublime encounters with real danger by climbing mountains or parachuting from airplanes. In art, the sublime is an Aesthetic experience, offering the thrill of danger but from a safe distance. Wordsworth is moved by “the lightning, the fierce wind, the trampling waves,” but he stands safely indoors, viewing a painting. Similarly, many people seek simulations of the sublime by riding on scary roller coasters or viewing horror films.

An experience of the sublime opens spiritual portals into the unfathomably distant, the mysteries of infinity. During the Romantic 19th Century, painters opened gateways between our experience of the world and the forces of creation and destruction.

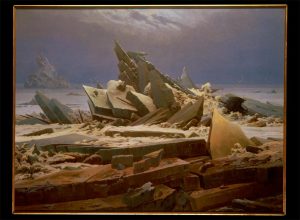

Caspar David Friedrich

A German Romantic painter, Caspar David Friedrich found “a quasi-religious feeling in Nature, enhanced by a melancholy cast of mind” (Friedrich, Caspar David). In his paintings, Friedrich evoked the Sublime in visions of grandeur, elevated places and destructive elements. Wanderer above the Sea of Mist iconically evokes the sublime–a reflective hiker looking out into infinity. Sea of Ice portrays the majestic destructiveness of arctic cold. Our perspective here is detached, the aesthetic sublime, but the title informs us that a ship has been lost. Scant evidence of the shattered ship and its human lives are almost completely obscured by the pitiless ridges of ice.

|

|

||

| Wanderer Above the Sea of Mist. (1818). | Sea of Ice (Arctic Shipwreck). (1824). | Cross on the Mountain (1811). | Winter Landscape. (1811) |

Cross in the Mountains (1808) challenges our sense of the boundaries of “religious art.” The cross rises from a landscape, not a church, initiating in its day “a debate on the propriety of such pantheistic implications” (Friedrich, Caspar David).

Frontier Sublime: the Hudson River School

The Hudson River School

a school of American painters who, in the middle decades of the 19th Century, took the themes of the Romantic Era into remote regions such as the Hudson River Valley. Innovators of a Genre of paintings that sought the Sublime in encounters with landscape that dwarfed human concerns

|

|

| Thomas Cole. (1836). Mount Holyoke after a Thunderstorm-The Oxbow. | Asher Brown Durand. (1859). The Catskills. |

Hudson River painters portrayed mountain and valley vistas from the Catskill mountains. Like Chinese landscape painters, they cultivated the sublime in vast panoramas that dwarfed human figures. In the Oxbow painting above, there is a tiny reference point for human perspective. Can you find it? The parasol on the lower right reaching across the river!

Frederick Edwin Church

Thomas Cole’s only student, Frederick Edwin Church developed the Hudson River School tradition: “he extended its romantic realism to treat unfamiliar, frequently awesome subjects with grander and more sensuous physical presence.” His sublime images span “the Americas, from the Arctic to equatorial South America (Church, Frederic Edwin).

|

|

|

| A Country Home. (1854). | Niagara. (1857). | Cotopaxi. (1862). |

Our three samplings from Church’s work move progressively into deeper dimensions of the Sublime. A Country Home transforms a typical pastoral scene by pulling back, minimizing the buildings, and drawing our eyes through the opening of the clouds into cosmic light. Niagara places our perspective on the brink of destruction, the sublime force pulling us downward toward the rocks. In Cotopaxi, another waterfall seems to transport us into a primordial moment of time in which the earth itself seems to be newly born.

The Biblical Sublime: Rembrandt

|

| Rembrandt van Rijn. Storm on Sea of Galilee. (1633). Oil on canvas. |

We have seen how Rembrandt’s Storm on the Sea of Galilee uses Chiaroscuro and Composition to probe the Theme of faith. Let’s return to it briefly as an example of the Sublime. Christians tend to view this painting in biblical terms. But what would eyes from a different religious tradition see if the title were set aside? An iconic example of the Sublime: we look safely on as men cling to a frail craft, beset by the lethal turbulence of a storm at sea.

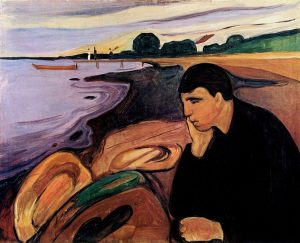

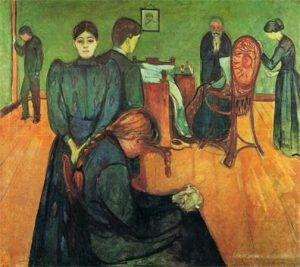

The Existential Sublime: Edvard Munch

At a glance, the work of Edvard Munch seems a far cry from sublime landscapes. You may well be familiar with Scream, a work as popular as it is puzzling. We don’t know anything about this tormented human figure. Unidentified agony distorts the artist’s technique, the shape of the figure’s body, and even the surrounding terrain. What could possibly be this disturbing?

|

|

|

| Scream. (11893). Oil, tempera, pastel and crayon on cardboard. | Melancholy. (1895). | Death in the Sickroom. (1892). |

Whatever it is, Melancholy seems to suggest that it pervades Munch’s imagination. Death in the Sickroom invokes the core spiritual issue that troubles people in every human culture: mortality, the specter of one’s own death. And that’s our next focus.

References

Beaumont, Sir George Howland. (1806). Peele Castle in a Storm. [Painting]. Grasmere, Cumbria, UK: Dove Cottage and the Wordsworth Museum. Wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sir_George_Howland_Beaumont_-_Peele_Castle_in_a_Strorm.jpg.

Church, F. E. (1854). A Country Home. [Painting]. Seattle, WA: Seattle Art Museum. ID Number 12074. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ASEATTLEIG_10312600010.

Church, F. E. (1857). Niagara. [Painting]. Washington, D.C.: Corcoran Gallery of Art. Accession Number 76.15. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ACORCORANIG_10313504857.

Church, F. E. (1862). Cotopaxi. [Painting]. Detroit, MI: Detroit Institute of Arts. Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/frederic-edwin-church/cotopaxi-1862.

Cole, T. (1836). View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm-The Oxbow. [Painting]. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/MMA_IAP_1039651537.

Durand, A. B. (1859). The Catskills. [Painting]. Baltimore, MD: The Walters Art Museum. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AMICO_WALTERS_103828096.

Friedrich, C. D. (1811). Winter Landscape. [Painting]. London: National Gallery. Accession Number NG6517. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ANGLIG_10313767145.

Friedrich, C. D. (1818). Wanderer Above the Sea of Mist. [Painting]. Hamburg, Germany: Kunsthalle. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AIC_930031.

Friedrich, C. D. (1823 – 1824). Sea of Ice (Arctic Shipwreck). [Painting]. Hamburg, Germany: Hamburger Kunsthalle. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/SCALA_ARCHIVES_1039930139

Friedrich, Caspar David, 1774-1840. (1808). Cross on the Mountain. Altarpiece: [Painting]. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822000653954.

Friedrich, Caspar David. [Article]. (2015). In T. Devonshire Jones, L. Murray, & P. Murray (Ed.s), The Oxford Dictionary of Christian Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199571123.001.0001/m_en_gb0317170.

Rembrandt van Rijn. (1633). Storm on Sea of Galilee. [Painting]. Boston, MA: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Stolen—whereabouts unknown. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822000427318.

Sublime. [Article]. (1999). In I. McCalman, J. Mee, G. Russell, C. Tuite, K. Fullagar, and P. Hardy (Ed.), An Oxford Companion to the Romantic Age. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780199245437.001.0001/acref-9780199245437-e-676.

Wordsworth, W. (1807). Elegiac Stanzas Elegiac Stanzas Suggested by a Picture of Peele Castle in a Storm, Painted by Sir George Beaumont. In Poems, in Two Volumes. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45516/elegiac-stanzas-suggested-by-a-picture-of-peele-castle-in-a-storm-painted-by-sir-george-beaumont.

an aesthetic effect in art in which the viewer or reader experiences awe, even fear in a representation that (safely!) carries the imagination into danger, terror, darkness, solitude, or infinity

a particular set of values regarding art, taste, and the subjective experience of beauty, ugliness, the sublime, etc. A culture, a school of artists, an individual artist, or an audience can be said to have an aesthetic

a late 18th and 19th Century reaction against neo-classical reason which sought to liberate the individual human imagination and embrace its passions, dreams, and irrational visions as sources of wisdom

a particular type of composition marked by expected, conventional features: e.g. Japanese haiku, Chinese landscape painting, Renaissance sonnet

in Italian, “light/dark,” a style of art that powerfully contrasts light and dark effects. Associated with Baroque painting, but common in the art of the early 20th Century: e.g. German expressionism and film noir cinema.

in visual art, the arrangement of visual elements for expressive and aesthetic impact: unity, proximity, similarity, variety and harmony, emphasis, rhythm, balance, etc.

a pattern of thought, value, and reflection that are evoked in a work of art.