Classical Traditions

Classical Egyptian Art

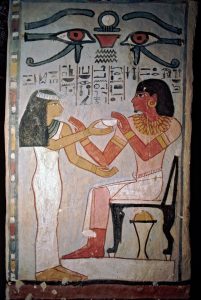

In Week 1, we looked at conventions of ancient Egyptian art that remained static for centuries. In Egyptian painting, “the eye is shown frontally in a profile face and the shoulders are turned round so as to be presented parallel to the picture plane” (Egyptian art). To view the image, we must embrace a double perspective: figures in profile; shoulders and eyes straight on.

|

|

| King Menkaura & queen. (25th C. BCE). | Meryt offers cup to Sennufer (c 1410 BCE). Tomb of Sennufer |

In Egyptian sculpture, feet stand flat on the ground, one advanced forward. Heads display standard, stylized features of a generic human face fused with totemic animals.[1] No movement or emotion disturbs a sense of static order, uninterrupted by time’s cycles. Unchanging rules and styles affirm a vision of perpetual Egyptian authority and prosperity.

This reliance on static rules and conventions is typical of “classical” art. Canonical styles affirm the ruling regime, its class, and its cultural values, assumed to be civilized and superior: We dominate because our sophisticated ways make us worthy to do so. Often tragically, classicism burdens oppressed social groups whose own cultural styles are cited as evidence of inferiority. Classical styles dominate a society’s image, breeding emulation and resentment.

[1] Totemic animals: animals associated with the gods

Samurai Classicism in Japan

An example of a Classical tradition can be found in medieval Japan. Yet this brand of classicism came into being by displacing an older model of classical aristocracy. In the 12th Century, the Japanese warrior class gained dominance in society by becoming a hereditary caste which alone retained the right to bear arms.

We think today of Samurai as warriors, and “their conduct was regulated by Bushido (Warrior’s Way), a strict code … of loyalty, bravery, and endurance” (Samurai). Yet Samurai culture was far more comprehensive than that, seeking cultural refinement in every area of life.

|

|

|

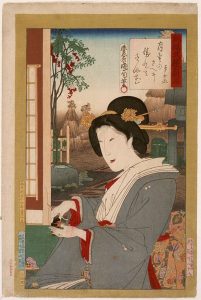

| Samurai. (1801 – 1806). Color Woodcut | Kunichika, Toyohara. (1883). Tea Ceremony. Woodcut. | Yasuimoku Komuten Company (2001) Facsimile of a Japanese Teahouse |

In an article on Japanese aesthetics, Ryōsu Ōhashi explains that 3 influences—Chinese Confucianism, Zen Buddhism, and the Shinto religion—coalesced in a commitment to a refined style of life. “Aesthetic egalitarianism,” claims Ōhashi, applied to all areas of life, martial arts, fine arts, and everyday arts: cooking, eating, bathing and entertaining visitors. Even the basest areas of life were raised to elegance through art and ritual.

Japanese aesthetics are deftly expressed in the tea ceremony, a “highly ritualized gathering of people” that sought four Zen principles: “harmony, purity, tranquility, and reverence.” Ritualized conventions govern not only the drinking of the tea, but the utensils that serve it, the architecture of the teahouse, and its connection with formal gardens.

Westerners observing art in the classical Japanese style will miss much of the significance of details in this cultural tradition. However, we can sense an ideal harmony of design and spirit in this silk screen variant on Chinese landscape painting.

|

| Tawaraya Sōatsu. (circa 1600-1628). Waves at Matsushima. Right panel of folding screen. |

Ryōsu Ōhashi explains that the Japanese sense of beauty is characterized by an Aesthetic of “Implication, Suggestion, Imperfection.” Many classical cultures prefer indirect methods of communication.

Haiku: Poetics of Indirection

In Japanese culture, civilized refinement lies in one’s ability to communicate with cool restraint, intimating rather than boorishly exclaiming emotions and messages. According to Saito, Japanese aesthetics seek indirection in every area of life and art, including haiku, a genre of poetry familiar to many American school children. Ueda explains that haiku challenged an earlier classicism, using humor “to liberate poetry from aristocratic court culture.”

You may recall that Haiku have an apparently simple form and rhythm: three lines and precisely 17 syllables. English translations of Japanese haiku strive to find correlative rhythms:[1]

crow is sitting

his autumn eve.

So OK, what do we see here? The plain sense of the poem appears to be pretty straightforward. The words sketch a poignant scene: branch, crow, autumn evening. We visualize the image with a sense of grace. But let’s recall the three themes that Ōhashi specifies: “Implication, Suggestion, Imperfection.” How do these three themes play out in the poem?

The haiku above was composed by the master Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694) who, according to Ueda. “elevated haiku to a mature poetic form by setting up high aesthetic ideals.” Ueda identifies two ideals that suggest typically classical refinement:

- sabi (loneliness) reinvented by Bashō, as “the pleasure of loneliness” as in “two old men” watching cherry blossoms who have “learned to accept the mutability of life.”

- karumi (lightness) which contrasts with the “‘heavy’ beauty” of “a poem dealing with a weighty philosophical theme

“Yet, it is not the opposite of ‘heaviness’” warns Ueda, “rather, it is a dialectic[2] transcendence[3] of it.” Haiku center on images of nature caught in seasonal moments which deftly suggest themes of mortality and the passing nature of time:

A successful haiku does not attempt to describe things in detail. … The writer (or observer) is only half of the process: the reader is the other half. Every haiku is almost asking the reader to be a poet too, by hopefully triggering an emotion or reaction. Haiku do not include the poet’s reaction to what is being observed. They hope to evoke a response in the reader from recorded observations (haiku).

[1] Translations of poetry are always extremely difficult. In addition to construing the sense of the lines, a translator of verse is faced with the daunting task of devising rhythms and figures of speech that emulate the idioms of the original language.

[2] Dialectic: an opposition between contrasting ideas—thesis v antithesis—that leads to a resolution in a 3rd term, the synthesis.

[3] Transcendence: rising above a current realm or state of affairs

|

|

| Kinkoku, Y. (after 1799). Portrait of Basho. Hanging scroll, ink and light color on paper. | Matsuo Bashō. (17th Century) Poetry Painting |

Try your hand at sensitively reading these samples of Haiku by Bashō. Before doing so, look at the “poetry painting” above. In contrast to Western art which mostly separates visual art from literary texts, the boundary between the two is much more fluid in Asian art. Remember that in Asian languages, words in a text are represented not by abstract phonetic letters, but by characters that are really word pictures. In Asian art, text often blends into the composition of the painting or sculpture.

Haiku composed by the 17th Century master Matsuo Bashō

An ancient pond!

With a sound from the water

Of the frog as it plunges in.

The cry of the cicada

Gives no sign

that presently it will die.

O ye fallen leaves!

There are far more of you

Than ever I saw growing on the trees!

Tis the first snow—

Just enough to bend

The gladiolus leaves!

Twas the new moon!

Since then I waited—

And lo! to-night!

[I have my reward!].[4]

[4] This last line in brackets is added by the translator to capture the implication of enigmatic, suggestive line three. Does it help or hinder?

How did your reading go? Perhaps you had a nice experience of ennui, of somber beauty. Yet this deceptively complex form has complex rhythms, as Ōhashi explains:

The “cutting word” in Haiku is often found at the end of the 1st or 2nd line. This rhythmic break encourages us to compare the 1st and 2nd images or themes. Below, the weary traveler’s yearning for rest is crosscut by a sudden vision transcending weariness. Structure and rhythm open up thematic contrasts. Can you see them?

In search of an inn—

Ah! these wisteria flowers!

References

Basho, M. (17th Century). Selected haiku. Trans. Aston, W. G. (1899). A History of Japanese Literature. London: William Heinemann. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Author:Matsuo_Bash%C5%8D

Basho, Matsuo. (circa 1644-1694). Poetry Painting. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/SS7731421_7731421_11103590

Egyptian Art [Article]. (2010). In M. Clarke & D. Clarke (Ed.). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780199569922.001.0001/acref-9780199569922-e-638

Haiku [Article]. (2018). The Hutchinson unabridged encyclopedia with atlas and weather guide. Abington, UK: Helicon. http://ezproxy.bethel.edu/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/heliconhe/haiku/1?institutionId=712

Hunting Scene [Fresco]. (ca. 1415 BCE). Thebes (Qurnah): Tomb of Menna (no.69). Accession Number 2Ak.172.2a. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AWSS35953_35953_31676036.

King Menkaura (Mycerinus) and queen [Sculpture]. (2490-2472 BCE). ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AMBOSTONIG_10313608722

Kinkoku, Y. (after 1799). Portrait of Basho. [Painting]. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, Museum of Art. ID Number: AAPD 7874. https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AAPDIG_10311726051.

Kunichika, T. (1883). In Daily Life of Tokyo Women. [Print]. Los Angeles, CA: Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Accession number M.74.104.2. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tea_Ceremony_LACMA_M.74.104.2.jpg.

Meryt offers cup to Sennufer (c 1410 BCE). Tomb of Sennufer. [Wall Painting]. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/KOZLOFF_1039786307.

Ōhashi, R. (2014). Japanese Aesthetics. (Parkes, G., Trans.) In Kelly, M. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Aesthetics. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780199747108.001.0001/acref-9780199747108-e-424

Samurai [Woodcut]. (1801 – 1806). San Francisco, CA: Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AMICO_SAN_FRANCISCO_103846066

Sōtatsu, T. (circa 1600-1628). Waves at Matsushima. Right panel of folding screen. Boston, MA: Freer Gallery of Art. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/SS33119_33119_15041636

Tea ceremony. [Article]. (2004). In D. Keown (Ed.), A Dictionary of Buddhism. Oxford University Press http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198605607.001.0001/acref-9780198605607-e-1816

Turnbull, S. (2001). Samurai. In R. Holmes (Ed.), The Oxford Companion to Military History. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198606963.001.0001/acref-9780198606963-e-1119

Ueda, M. (2014). Haiku. In M. Kelly (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Aesthetics. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780199747108.001.0001/acref-9780199747108-e-350

Yasuimoku Komuten Company Ltd. (2001). Japanese Teahouse. Minneapolis, MN: Minneapolis Institute of Art. G225 Gallery. https://collections.artsmia.org/art/59614/teahouse-yasuimoku-komuten-company-ltd

characteristic features—subject matters, themes, techniques, styles—that define a genre or artistic tradition and are expected and understood by the audience in its context

in the Euro-American tradition, a reference to the works, styles, and themes of Greek and Roman antiquity. More generally, an aesthetic valuing clarity, order, balance, unity, symmetry, and dignity, usually honoring a cultural tradition associated with some golden age of the past.

often contrasted with “romantic” folk traditions, an aesthetic associated with a social elite and a venerated past, especially ancient Greece and Rome. Characterized by clarity, order, balance, symmetry, reason, mathematical precision

a print technique in which a design is carved in wood, inked, and pressed on paper

a particular set of values regarding art, taste, and the subjective experience of beauty, ugliness, the sublime, etc. A culture, a school of artists, an individual artist, or an audience can be said to have an aesthetic

a Japanese poetical genre dating from the 17th Century in which 17 syllables deftly evoke a poignant scene contrasting sabi (loneliness) with karumi (lightness) through a cutting syllable which both continues and shifts the poem’s theme