Portraiture

All families face the core human challenge: time, decay, and loss. How can art help preserve the image and identity of loved ones? Human figures in ancient art are often funerary. This sarcophagus—i.e. coffin—represents the loving union of a husband and wife.

|

| Sarcophagus of the married couple. (circa 520 BCE). Etruscan culture. Terracotta |

As does funerary art in many cultures, the coffin is topped with an effigy preserving the memory of the deceased. But is it a portrait? The Columbia Encyclopedia’s definition of portraiture emphasizes its role in preserving identity against the corrosive impact of time:

Portraiture is a branch of Representational Art (also known as Figurative Art) which depicts images that can be recognized from the real world. Of course, we approach the image from our own perspective. Centuries of post-Renaissance portraiture and nearly two centuries of photography lead many in the Euro-American West to expect Mimetic, imitative realism. A “good” portrait, many feel, would capture the idiosyncrasies of an individual’s appearance and character. So, what do you think of the representational technique in the Etruscan effigy? How vividly do you see the husband and wife as individuals?

Well, perhaps not so well. Representational Art presents visual subjects that we can recognize. But how? A great deal of world art effectively evokes subjects, not through meticulous imitation of individual features, but through generic ideas. The image of our Etruscan couple makes little attempt to capture the specific look of the individuals. Its features–braided hair, pointed facial features, fixed, dreamy smiles–are Conventional, shared by all the members of the couple’s affluent social class. The Stylized tecnique testifies to a culture in which people wish to be remembered for their status rather than through distinctive profiles.

In the long history of art, Stylized Representation is actually far more pervasive than Mimetic attention to visual detail. In our day, cartoonists and advertisers suggest characters, emotions, and actions with a few deft strokes of a pen. We find these techniques comfortable and convincing because they have become conventional. We “see” in images of Charlie Brown, Lucy, and Linus convincing depictions of child characters whom we know from repeated experience and from narratives that make them live for us. Yet few would argue that Charles’ Schultz’s spare sketch lines meticulously capture the faces of children.[1]

[1] While images from Charles M. Schultz’s Peanuts comic strip are well known around the world, open source images are hard to come by. To sample some of Schultz’s stylized representations of children, try this website: https://www.peanuts.com/.

Most ancient art relied on Stylized features. What conventional, stylized features do you see in these figures from Xochipala Culture figures (Mexico) formed from red-brown micaceous ceramic? What can we plausibly infer about the artistic values motivating these artists from a distant culture?

|

|

|

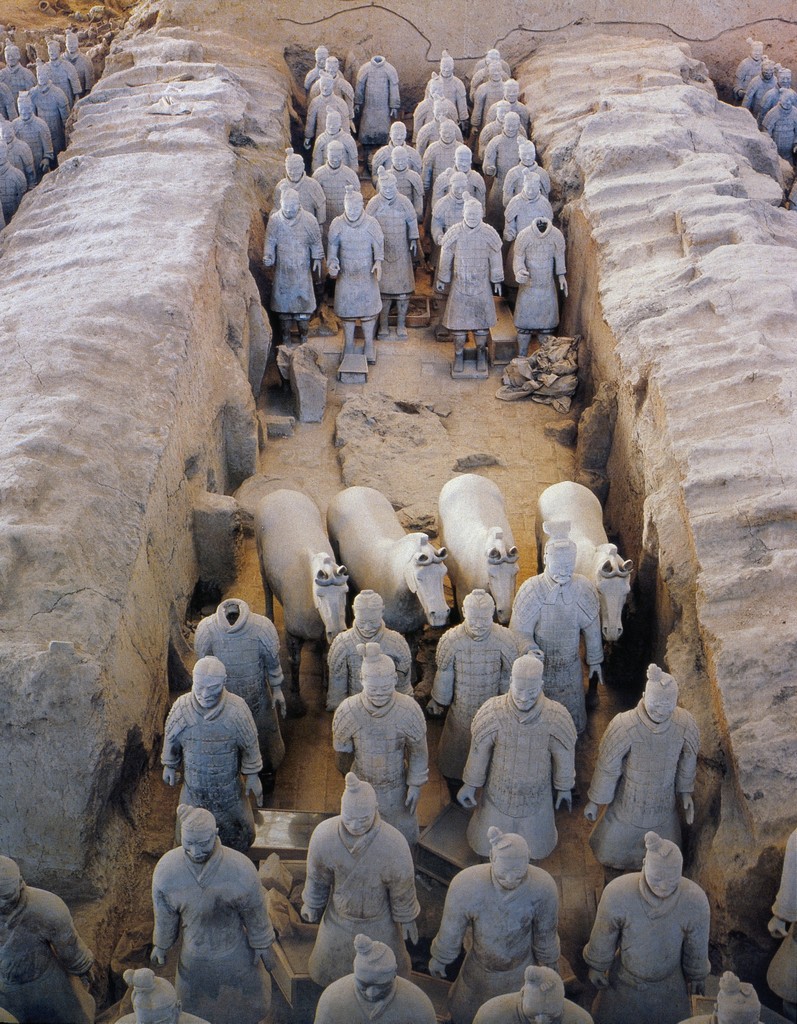

| Seated shaman and youth. (400 B.C. – A.D. 500). | Female Figure. (circa 15th-10th century BCE). | Tomb of Ch’in Shih-Huang-Ti. (c 246-210 B.C). Standing soldiers and horses. [Terracotta statues]. |

If we define portraiture in terms of the distinctive appearance of the individual, Portraiture was rare in ancient cultures. Yet, Ch’in Shih-Huang-Ti’s famous terracotta army offers an interesting case. In 1974, excavations uncovered the tomb of China’s first emperor. The emperor is guarded by more than 7,500 life size figures, an army of soldiers and horses projecting imperial power into the afterlife. The army was intentionally buried, unknown for 2,300 years.

A close look at the figures seems to suggest that these are portraits of individuals. Each figure has different features: shape of head, beard, expression, facial features. An even closer look, however, shows that the appearance of individuation is misleading. The artists worked with half a dozen distinct templates for each component of a figure’s appearance: head, beard, expression, etc. By mixing and matching these stylized components, the artists achieve hundreds of “individual” figures.

Ancient Chinese and Roman artistic traditions composed individualized portraits of particularly famous heroes. The portrait of Confucius, “one of the great cultural heroes of Chinese history was most likely used in a temple or at an altar dedicated to his system of thought” (explanatory note for the MIA image). Composed long after the sage’s life ended, it displays an artist’s imagined rendering drawing on conventional ideas of the master.

|

|

| Portrait of Confucius. (14th C). Ming dynasty. Ink and colors on silk scroll |

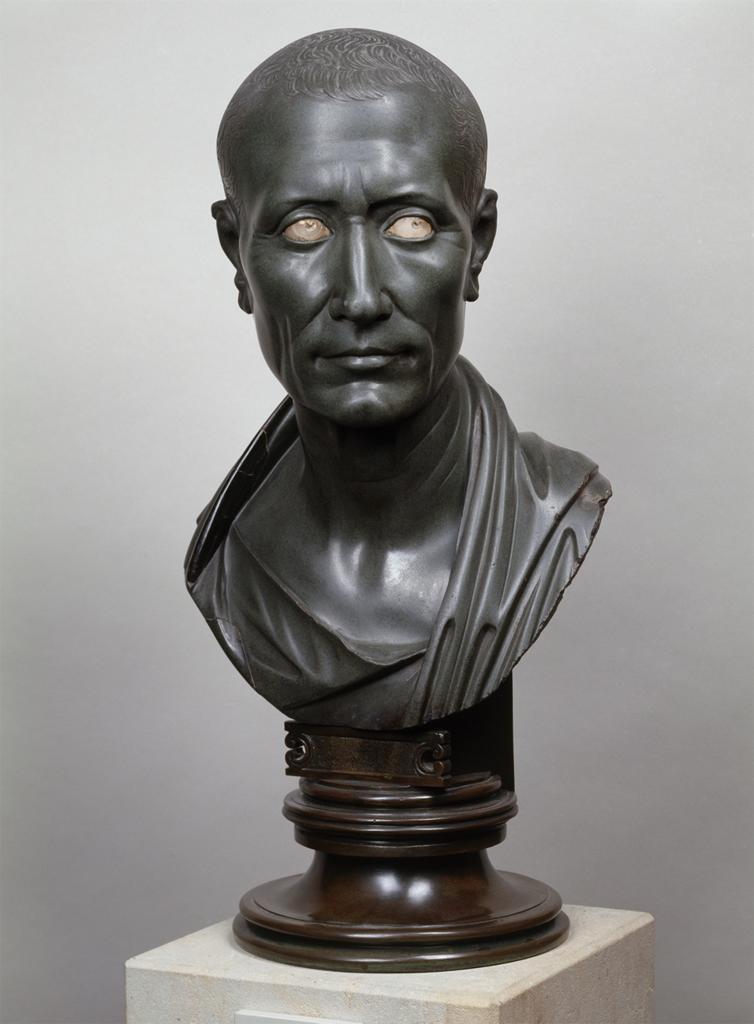

Bust of Julius Caesar. (1st century BCE). Green granite and white glass

|

The bust of Caesar below reflects a more direct knowledge of the emperor’s actual person. Next week, we will explore the emergence of Roman realism out of Classical Greek art. The art which flourished in Rome during the time of the Caesars virtually copied Greek techniques. Does this Mimetic approach seem more “evolved” to us today? Does that response reflect our own cultural orientations?

During the reign of Julius Caesar, Ptolemaic Egypt was absorbed into the Roman Empire. For about 3 centuries, northern Africa, centered in Alexandria, provided the grain which fed the Empire. Roman citizens owned plantations which grew the grain using slave labor. Over this time, the cultures fused, as they tend to do in colonial contexts.

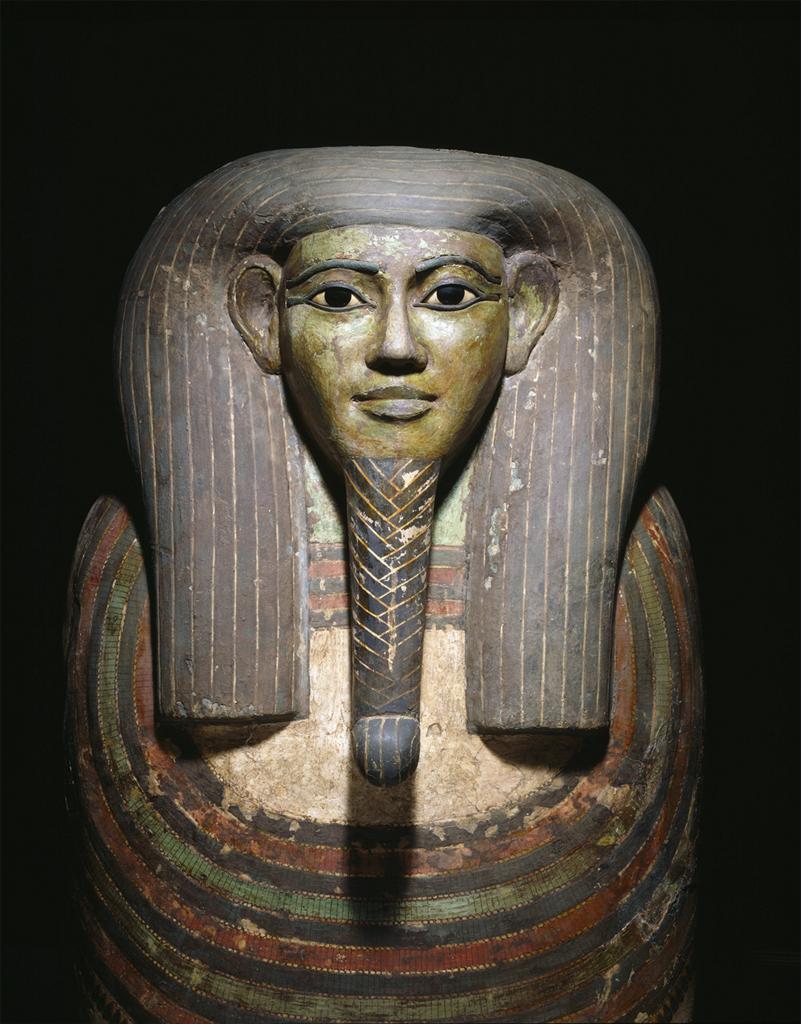

Of course, Egyptian culture is famous for embalming deceased bodies. A mummy was traditionally housed in a sarcophagus with an effigy placed over the face within. These traditional effigies were highly stylized, with little attempt to depict the individual faces of the deceased.

|

|

|

| Coffin of Horankh. (c. 700 BCE). Wood, paint, bronze | Mummies with Child Portraits. (c. 50 CE). | Funerary Portrait. (2nd C.). Encaustic on wood |

During the Roman era in Egypt, the process of mummification was maintained, but the style of the effigies on the coffin changed radically. The deceased began to be remembered in individualized portraits influenced by Roman art traditions. The faces of these two mummified children look at us with a startlingly life-like intensity. (Are they a bit creepy?) The funerary portrait of the young lad would seem to fit into a family’s photo album today.

As we will see next week, the Classical traditions of Greece and Rome that pioneered Mimetic art were cut off by the Byzantine era’s commitment to stylized Christian art. A thousand years later, the concept of the portrait was revived in the Renaissance period. During the Baroque and neo-Classical eras that followed, family portraiture evolved as it became a virtual requirement in elite society. Painters refined their techniques for flattering their patrons’ self-images. In the group composition by Franz Hals, notice the individuated faces and motivations. As the adults sit formally, the youngsters twitch with suppressed energy. Notice, too, the lighting! We’ll have more to say about that next week.

|

|

|

| Franz Hals. (c 1650). Family Group in a Landscape. Oil on canvas. | Joshua Reynolds. (1777). Lady Elizabeth Delmé and her children. Oil on canvas. | John Singer Sargent. (ca. 1892-1893). Lady Agnew. Oil on Canvas. |

Joshua Reynolds was one of the predominant English portrait painters of the 18th Century. Above, he composes Lady Delmé and her children in an intimate grouping. Don’t miss the landscape which is the family’s pride and joy: a great country estate, sign of enormous wealth. But beware of appearances! Lady Delmé might or might not have loved her children, but she would have had little contact with them as they were raised by wet nurses, nannies, and governesses, the “young gentlemen” sent off to public (boarding) school at the age of 5 or 6.

The American painter John Singer Sargent made his name and fortune portraying America’s elite and British nobility. His portrait of the Scottish Lady Agnew illustrates the great skills of portraiture that had developed over 400 years.

Until the 19th Century, the idea of preserving one’s image in a portrait was a privilege reserved only for the extremely wealthy and powerful. Indeed, the whole concept of faithfully recording the appearance of an ordinary person was repugnant to the preference for nobility in art. Yet values began to change in the 19th Century, and we find here Jean-François Millet’s honoring a moment of piety for two humble peasants in France.

|

|

| Jean-FrançoisMillet. (1857-1859). The Angelus. Oil on canvas | Hill & Adamson. (ca. 1845). Jeanie Wilson & Annie Linton, Newhaven Fisherwomen. Salted paper print. |

How many images do you have of your children and grandchildren? Of the children of friends who text you 15 times a day? Well, before the age of the photograph, portraits were almost never available to working people. Only the wealthy and exalted could patronize artists. And then, in the mid-19th Century, the camera came along and brought portraiture to common people. In 1845, Jeanie and Annie Linton could not even imagine having the funds to sit for painted portraits. Yet here they are, captured in a photographic print. Painters now faced competition from a medium affordable to common people and reflective of a growing social awareness of the significance of lives not cushioned by wealth. Artists and writers of the Romantic Era (Week 4) embraced more humble walks of life.

References

Coffin of Horankh. (c. 700 B.C.). Dallas, TX: Dallas Museum of Art. Artstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AMICO_DALLAS_103843037.

Female Figure. [Ceramics]. (circa 15th-10th century BCE). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Artstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/SS7731421_7731421_11046816.

Hals, F. (circa 1650). Family Group in a Landscape. London: National Gallery. Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/frans-hals/family-group-in-a-landscape-2.

Millet, Jean-François. (1857-1859). The Angelus. [Painting]. Paris: Musée d’Orsay. Artstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_10310751251.

Portrait of Confucius. [Painting]. (late 14th century). Minneapolis, MN: Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Artstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AMICO_MINIAPOLIS_103823924.

Portraiture [Article]. (2018). P. Lagasse, & Columbia University, The Columbia Encyclopedia (8th ed.). New York, NY: Columbia University Press. http://ezproxy.bethel.edu/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/topic/portraiture?institutionId=712.

Representational Art [Article]. (2018). Helicon (Ed.), The Hutchinson unabridged encyclopedia with atlas and weather guide. https://ezproxy.bethel.edu/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/heliconhe/representational_art/0?institutionId=712.

Reynolds, Joshua. (1777). Lady Elizabeth Delmé and her children. [Painting]. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art. Artstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ANGAIG_10313967175.

Sarcophagus of the married couple. (c 520 BCE). Paris: Musée du Louvre. Artstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/LESSING_ART_10311441963;prevRouteTS=1602183916331.

Sargent, John Singer. (ca. 1892-1893). Lady Agnew. [Painting]. Edinburgh: National Gallery of Scotland. Artstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AIC_40038.

Seated shaman and youth. [Ceramics]. (400 B.C. – A.D. 500). Artstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/APRINCETONIG_10313684775.

Standing soldiers and horses. [Ceramics]. (ca. 246-210 B.C). China: Tomb of Ch’in Shih-Huang-Ti. Artstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822003053384

Two Mummies with Portraits of Children. (c. 50 CE). Berlin: State Museum of Berlin. Artstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_10311441675.

in visual art, compositions that represent human subjects as individuals, meticulously capturing physical or psychological likenesses

images that depict or emulate recognizable objects in a theoretical “real world.” Art is representational even if it distorts the designated object as in stylized or surreal art. The opposite is abstract, or non-figurative, art.

in visual art, the quality of imitating as closely as possible the appearance of nature, “the real thing." Often contrasted with stylized technique

in visual art, a representational technique that depicts visual subjects through simplified, exaggerated, or conventional forms rather than through meticulous mimesis

a function of visual art which seeks to depict a visual subject that viewers will recognize from a theoretical “real world.” Opposite: abstract or non-figurative art

in the Euro-American tradition, a reference to the works, styles, and themes of Greek and Roman antiquity. More generally, an aesthetic valuing clarity, order, balance, unity, symmetry, and dignity, usually honoring a cultural tradition associated with some golden age of the past.

an era in 15th and 16th century Europe marked by a Renaissance—or rebirth—of interest in and knowledge of classical Greek learning through humanist scholarship that challenged medieval values. In painting and sculpture, the work of artists in Italy, Germany, and the Low Countries which broke with Byzantine conventions to explore the geometry of perception and locate images and actions in time and space

the 17th Century artistic tradition that followed the Renaissance, characterized by dramatic action, intense passions, chiaroscuro, and gritty social realism. More broadly, any art emulating the values of the Baroque

a style of art that emulates a former classical age, generally emphasizing conventional rules, mathematical precision, and reason over passion.

a late 18th and 19th Century reaction against neo-classical reason which sought to liberate the individual human imagination and embrace its passions, dreams, and irrational visions as sources of wisdom