Israel’s Literary Artistic Tradition

For Jews, Christians, and Muslims, one tradition of Didactic literature with special importance is that of the ancient Jews.[1]

|

|

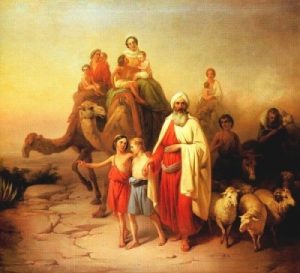

| Mizrah (East plate). (17th Century). Manuscript | Molnar, Jozsef. (1850). Abraham’s Journey from Ur to Canaan. Oil on canvas. |

The people of ancient Israel were among the Semitic tribes who migrated into and out of Mesopotamia. Israelites recognize the birth of their ethnic identity in the patriarch Abraham’s faithful obedience to God’s command to go out from his Mesopotamian home in Ur of the Chaldeans and journey to Canaan, later known as Palestine. We read the tale of Abraham’s founding journey in the first book of Torah,[2] Genesis 11.27-12.9.

[1] You may be surprised to hear that the Jewish tradition of scriptures is important to Muslims. However, as all Muslims know, the Prophet Muhammad was inspired in his faith by the Judeo-Christian heritage and saw himself as a prophet in the line of Abraham, Isaiah, and Jesus. The Koran draws frequently on Jewish scriptures and honors Jesus as a great prophet.

[2] Torah: Hebrew scriptures are divided into three sections, Torah, (books of the law), Nevi’im, (books of the prophets) and Ketuvim (books of wisdom). Torah, later known to Greek and Latin scholars as the Pentateuch, consists of the first 5 books of both Hebrew scripture and the Christian Bible: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy.

Now the Lord said to Abram, “Go from your country [Ur of the Chalde′ans] and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you. And I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you, and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing. I will bless those who bless you, and him who curses you I will curse; and by you all the families of the earth shall bless themselves.”

So Abram went, as the Lord had told him; and Lot went with him. Abram was seventy-five years old when he departed from Haran. And Abram took Sar′ai his wife, and Lot his brother’s son, and all their possessions … and they set forth to go to the land of Canaan.

When they had come to the land of Canaan, Abram passed through the land to the place at Shechem, to the oak of Moreh. At that time the Canaanites were in the land. Then the Lord appeared to Abram, and said, “To your descendants I will give this land.” So he built there an altar to the Lord, who had appeared to him. Thence he … pitched his tent, with Bethel on the west and Ai on the east; and there he built an altar to the Lord and called on the name of the Lord.

The Israelites rejected the multiple gods of the peoples around them and the habit of worshiping idols depicting the gods as animals and persons. In Exodus 20:4-6, Moses warns the people of Yahweh against forming idolatrous images:

You shall not make for yourself an image in the form of anything in heaven above or on the earth beneath. … You shall not bow down to them or worship them; for I, the Lord your God, am a jealous God.

This abhorrence of idolatry conditioned Jews and the spiritual traditions that descended from them—Christianity[3] and Islam—to turn away from religious imagery in their art forms. Though they have vastly influenced the world, the People of Israel have left few paintings or sculpture. Jewish art took a very different form: the composition and loving preservation of texts. Through millennia of exile, persecution and even genocide, Jews have miraculously preserved their culture through devotion to their literary tradition of scripture.

[3] Christians have always shared the Hebrew abhorrence of idolatrous worship of other gods. However, since Christians see Jesus as an incarnate god who adopted a human body, a long tradition of religious iconography developed in the early Centuries of the faith. We will sample this tradition. It should be noted, however, that iconoclasm, a religiously inspired revulsion against Christian images of Christ, Mary, and the saints popped up in a few periods of Christian history to attack icons as idolatry. With some exceptions, Protestant traditions minimize the use of religious images.

Hebrew scripture (for Christians, the Old Testament) centers on God’s call to the Israelites to be His people, follow his laws, and trust in His protection. Torah celebrates the providence of the God who called them to a special and lasting communion. The way has not been easy: Abraham’s journey leads to slavery in Egypt and a migration personally blessed by God:

The Lord said, “I have indeed seen the misery of my people in Egypt. I have heard them crying out because of their slave drivers, and I am concerned about their suffering. So I have come down to rescue them from the hand of the Egyptians and to bring them up out of that land into a good and spacious land, a land flowing with milk and honey.

Journeying from Egypt to the Land of Canaan, the Israelites follow divinely inspired prophets and judges. In time, the people begin to grumble: they lack the national glory of a royal house: “So all the elders of Israel gathered together and came to Samuel at Ramah. They said to him, ‘You are old, and your sons do not follow your ways; now appoint a king to lead us, such as all the other nations have’” (1 Samuel 8.4-5). Grudgingly, Samuel anoints Saul as King of the Israelites. When Saul’s reign turns sour, Samuel is called by God to journey to Bethlehem to anoint a successor from among the sons of Jesse.

“Do not consider appearance or height. … The Lord does not look at the things people look at. People look at the outward appearance, but the Lord looks at the heart.” …

So he asked Jesse, “Are these all the sons you have?”

“There is still the youngest,” Jesse answered. “He is tending the sheep.”

Samuel said, “Send for him; we will not sit down until he arrives.” So he sent for him and had him brought in. He was glowing with health and had a fine appearance and handsome features. Then the Lord said, “Rise and anoint him; this is the one.” So Samuel took the horn of oil and anointed him in the presence of his brothers, and from that day on the Spirit of the Lord came powerfully upon David.”

You may be thinking, I’ve seen these story elements before. You have, in hundreds of stories—Aladdin, Hamlet, Elizabeth I of England, Jane Eyre, Frodo Baggins, Sgt. York, Luke Skywalker, Harry Potter. Each of these heroes is a youthful innocent reluctantly caught up in a conflict with threatening forces. These story elements are found in tales throughout the world. Particular features of the hero’s journey are found to run parallel to each other in many cultural traditions:

Archetype

In a traditional tale told by the Samish people of the Northwest Coast of the Pacific, Ko-Kwal-alwoot archetypal heroism takes the form of marriage. Known today as the Maiden of Deception Pass, Ko-Kwal-alwoot is courted by a suitor who carries the cold of the sea and bargains with the maiden and her father: if Ko-Kwal-alwoot will marry him and join him in the sea, her people will be blessed by an abundance of fish. Here magical, sacrificial marriage provides generations of abundancefor her people (link).

David, too, can be considered an archetypal hero. He initially resists the challenge of his calling. He hides in a cave to escape the wrath of jealous King Saul. Then, with Saul’s armies quailing in battle with Philistine opponents, the unlikely hero saves the day.

A champion named Goliath, who was from Gath, came out of the Philistine camp. His height was six cubits and a span. … Goliath stood and shouted to the ranks of Israel, … “Choose a man and have him come down to me. If he is able to fight and kill me, we will become your subjects; but if I overcome him and kill him, you will become our subjects and serve us.”

As the Israelite soldiers hang back in dread of the massive champion, David arrives at the front, “glowing with health and handsome.”

David said to Saul, “Let no one lose heart on account of this Philistine; your servant will go and fight him.” Saul replied, “You are not able to go out against this Philistine and fight him; you are only a young man, and he has been a warrior from his youth.”

But David said to Saul, “Your servant has been keeping his father’s sheep. When a lion or a bear came and carried off a sheep from the flock, I went after it, struck it and rescued the sheep from its mouth. When it turned on me, I seized it by its hair, struck it and killed it. Your servant has killed both the lion and the bear; this uncircumcised Philistine will be like one of them, because he has defied the armies of the living God. The Lord who rescued me from the paw of the lion and the paw of the bear will rescue me from the hand of this Philistine.”

Goliath is not impressed by the youth who alone dares to face him: “Am I a dog, that you come at me with sticks? … Come here …and I’ll give your flesh to the birds and the animals!” The story culminates in flash of combat and a grisly finale envisioned in many a Christian painting of later centuries:

David chose five smooth stones from the stream, put them in the pouch of his shepherd’s bag and, with his sling in his hand, approached the Philistine. … “You come against me with sword and spear and javelin, but I come against you in the name of the Lord Almighty, the God of the armies of Israel, whom you have defied. This day the Lord will deliver you into my hands, and I’ll strike you down and cut off your head. …The whole world will know that there is a God in Israel. All … will know that it is not by sword or spear that the Lord saves; for the battle is the Lord’s.”

As the Philistine moved closer to attack him, David … reached into his bag and taking out a stone, he slung it and struck the Philistine on the forehead. The stone sank into his forehead, and he fell face down on the ground. So David triumphed over the Philistine with a sling and a stone. … After he killed him, he cut off his head with the sword.

|

| Caravaggio, Michelangelo Merisi da. (ca. 1601-1602). David and Goliath. Oil on canvas. |

So the hero prevails over the villain. 2,500 years ago, the Greek philosopher Aristotle analyzed core narrative elements:

Central conflict driving narratives

Agon: the central conflict driving a narrative

Protagonist: the hero character with whom the narrative perspective identifies and whose interests the reader shares

Antagonist: the hero’s opponent in opposition to the narrative and reader perspective

Of course, villain and hero are matters of perspective. Even while making his promise to Moses, God had acknowledged that the “land of milk and honey” was inhabited by “Canaanites, Hittites, Amorites, Perizzites, Hivites and Jebusites” (Exodus 3.8). To these peoples, the Israelite migration was an invasion, and generations of warfare followed. For Jews, Christians, and Muslims, David’s faithful heroics provide the inspiration and the lessons that support the faith.

Hebrew Verse and Its Descendants

With their artistic energies focused on literature and scripture, the Jewish People have long been known as “the people of the book.”[5] Jewish and Christian worship is drenched in its spirituality and wisdom. And in the poetic textures of Hebrew verse.

[5] When Islamic armies conquered Asia Minor, Palestine, northern Africa, and Spain in the 7th and 8th Centuries CE, Jews and Christians were afforded limited privileges as the “people of the book,” the Hebrew and Christian scriptures which inspired Muhammad and are honored by Muslims to this day.

Wait, what? Old Testament texts are poems? Well, not all of them. But the Psalms, the Prophets, and the books of wisdom are written primarily in verse. Consider the famous Wisdom in the Streets passage from the Book of Proverbs.

Call of Wisdom (Proverbs 1:20-33)

Wisdom cries out in the street;

in the squares she raises her voice.

At the busiest corner she cries out;

at the entrance of the city gates she speaks:

“How long, O simple ones, will you love

being simple?

How long will scoffers delight in their scoffing

and fools hate knowledge?

Give heed to my reproof;

I will pour out my thoughts to you;

I will make my words known to you.

Because I have called and you refused, have

stretched out my hand and no one heeded,

and because you have ignored all my counsel

and would have none of my reproof,

I also will laugh at your calamity;

I will mock when panic strikes you,

when panic strikes you like a storm,

and your calamity comes like a whirlwind,

when distress and anguish come upon you.

Then they will call upon me, but I will not answer;

they will seek me diligently, but will not find me.

Because they hated knowledge

and did not choose the fear of the Lord,

would have none of my counsel,

and despised all my reproof,

therefore they shall eat the fruit of their way

and be sated with their own devices.

For waywardness kills the simple,

and the complacency of fools destroys them;

but those who listen to me will be secure

and will live at ease, without dread of disaster.”

Oratorical Rhythm: Figures of Speech

The rhythms of Hebrew verse operate through Figures of Speech: forms of expression in which language departs from conventional norms in its patterns (Scheme) or meaning (Trope) for maximum rhetorical effect. Shared by many languages, they are recognizable even in translation. For now, let’s briefly look at two:

Figures of Speech

- Anaphora: a figurative scheme that repeats the same word or phrase at the beginning of sentences or clauses

- Parallelism: a figurative scheme which arranges phrases, clauses or sentences with the same syntactic or thematic forms

Try to see these figures in the Wisdom in the Streets passage. Notice the repetitions of phrases, expressions, and syntactic structures. These subtle patterns achieve a poetic rhythm just as effective as rhyme or meter. Perhaps you didn’t recognize the subtle rhythms of Hebrew verse. But do they sound familiar? They should: orators (politicians, preachers) use these same verbal patterns to enthrall audiences and enhance listeners’ memory.

|

| Adelman, Bob. (1963). Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” Speech. |

Many of us are familiar with Dr. Martin Luther King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech from the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963). The most often quoted passages from the speech reverberate with Parallelism and Anaphora.

“I Have a Dream” Speech by Martin Luther King, Jr.

I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out … its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.”

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and … of former slave owners will … sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, … of oppression, will be … an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

I have a dream today!

I have a dream that one day, down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, … one day right there in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.

I have a dream today!

… This is our hope, and this is the faith. …

With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith, we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith, we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

And this will be the day — this will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with new meaning.My country ’tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the Pilgrim’s pride, From every mountainside, let freedom ring! …

And so let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire.

Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York.

Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania.

Let freedom ring from the snow-capped Rockies of Colorado.

Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California.

But not only that:

Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia.

Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee.

Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi.

From every mountainside, let freedom ring.

And when this happens, and when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual:

Free at last! Free at last!

Thank God Almighty, we are free at last.

The best way to experience this speech is to listen to it. One can distinctly hear the rhythms of oratory rhetoric in King’s masterful delivery. Of course, the passage above is only an excerpt from the speech. You can read and listen to the entire speech in a clip from NPR’s Talk of the Nation. The famous passage begins at the 11:26 mark of the recording.

Poetry? I’ve got no use for poetry. It’s a common viewpoint in our day. But the rhythms of verse pervade our lives from songs to the Hebrew prophets to poetic oratory. What do you think of poetry? You will do well to listen for poetic rhythms all around you.

Carl Sandberg: Poetry of Working life

Shakespeare affirmed his culture by dramatizing the glory and tragedy of its kings and nobles. America’s myths are democratic, steeped in the lives of ordinary citizens. Among the most committed of the nation’s democratic voices was that of the Illinois poet Carl Sandberg. Like many poets of the early 20th Century, Sandberg composed Free Verse. We hear his rhythms much better if we apply what we have just learned from Hebrew verse and oratory.

|

| Portrait of Carl Sandberg, c. 1925 |

Carl Sandberg (1924). “Chicago”

Hog Butcher for the World,

Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat,

Player with Railroads and the Nation’s Freight Handler;

Stormy, husky, brawling,

City of the Big Shoulders:

They tell me you are wicked and I believe them, for I have seen your painted women under the gas lamps luring the farm boys.

And they tell me you are crooked and I answer: Yes, it is true I have seen the gunman kill and go free to kill again.

And they tell me you are brutal and my reply is: On the faces of women and children I have seen the marks of wanton hunger.

And having answered so I turn once more to those who sneer at this my city, and I give them back the sneer and say to them:

Come and show me another city with lifted head singing so proud to be alive and coarse and strong and cunning.

Flinging magnetic curses amid the toil of piling job on job, here is a tall bold slugger set vivid against the little soft cities;

Fierce as a dog with tongue lapping for action, cunning as a savage pitted against the wilderness,

Bareheaded,

Shoveling,

Wrecking,

Planning,

Building, breaking, rebuilding,

Under the smoke, dust all over his mouth, laughing with white teeth,

Under the terrible burden of destiny laughing as a young man laughs,

Laughing even as an ignorant fighter laughs who has never lost a battle,

Bragging and laughing that under his wrist is the pulse, and under his ribs the heart of the people,

Laughing!

Laughing the stormy, husky, brawling laughter of Youth, half-naked, sweating, proud to be Hog Butcher, Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat, Player with Railroads and Freight Handler to the Nation.

Traditionally, art that celebrates culture weaves a vision of social virtue to justify the authority and ascendancy of the elite. Sandberg celebrates the virtues of work and working people. But he also insists on a realistic vision that embraces both vices and virtues. Chicago is a great town, Sanders argues, not because it is pure and righteous, but in spite of its corruption, prostitution, unpunished gun violence, and the poverty suffered by so many citizens.

References

Adelman, Bob. (1963). Martin Luther King at March on Washington DC. 1963. [Photograph]. New York: Magnum Photos. https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AMAGNUMIG_10311545416.

Archetype. [Article]. (2012). In D. Birch & K. Hooper (Eds.) The Concise Oxford Companion to English Literature. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199608218.001.0001/acref-9780199608218-e-319

King, M. L. (August 28, 1963). “I have a dream” speech in its entirety. Talk of the Nation. [Radio Broadcast]. January 18, 2010. National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/2010/01/18/122701268/i-have-a-dream-speech-in-its-entirety.

Sandberg, Carl. (1914). “Chicago.” In Poetry: Magazine of Verse. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poems/12840/chicago.

Portrait of Carl Sandberg. [Photograph]. (circa 1925). Bowdoin Institute of Modern Literature. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/SS7729815_7729815_8299940.

a quality of art that strives to teach information, instruct behavior, or advocate for an ideology, theology, or morality

(books of the law), first of three divisions of Hebrew scripture, followed by Nevi’im, (books of the prophets) and Ketuvim (books of wisdom). Translated into Greek and Latin, the Pentateuch, the first 5 books of the Christian Bible: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy

a figurative scheme which arranges phrases, clauses or sentences with the same syntactic or thematic forms: e.g. “We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender” (Winston Churchill, House of Commons address, 6/4/1940).

a figurative scheme that repeats the same word or phrase at the beginning of sentences or clauses: e.g. “I have a dream …” phrase repeated in Dr. Martin Luther King’s speech, (8/28/1963).

(in French, vers libre) achieves verbal rhythms through repetitive, often parallel figures of speech, Tropes and Schemes. Free verse does not establish set patterns of syllables, stresses, or rhymes.