Challengers of Academic Art

In the late 19th Century, European artists began to challenge the Renaissance Model of painting. In various ways and to varying degrees, these artists shifted the focus from the visual subject to aspects of the medium. As the rebellions grew increasingly extreme, they left audiences uncomfortable. Even today, people often feel put off by “modern art.”[1]

A great way to give these challenging artists a fair chance is to bring to bear the concepts from our last section. By exploring the Formal Art Elements of Composition, we can stop asking But what is it supposed to be? and get into the visual games these artists are playing.

[1] Modern art: this term is often used quite loosely to refer to styles of art that confuse viewers, often through unconventional representational techniques. The term is often unclearly associated with the modernist period of the 20th Century.

Impressionism

In the 1870s, artists such as Eduard Manet, Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Berthe Morisot, and Claude Monet offended the French art world by being perceived as “hostile to good manners, to devotion to form, and to respect for the masters.” These artists who struggled to have their work included in shows certified by the Academie des Beaux Arts rebelled …

The conventional art world of the dayobjected to what they saw as raw, unrefined craftsmanship: “their vigorous brushwork looked sloppy and unfinished, and their colors seemed garish and unnatural” (Impressionism 2015). The model of Academic Art insisted that the painter work meticulously in a studio, working and reworking oil paint until the subjects seemed perfectly natural and all marks of the medium were submerged in the illusion of a seen reality. But these artists were not ineptly playing by post-Renaissance rules. They were playing a whole new sport.

Claude Monet

Impression–the Label

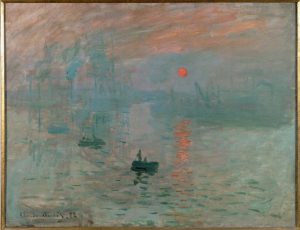

OK, so let’s look at this painting that bothered the critic enough to derisively name a movement. What is it supposed to be?

|

| Claude Monet. (1872). Impression, Sunrise. Oil on Canvas. |

At the center of the image, we see a small boat, with more receding into the distance. The waves of the sea are pretty clearly visible, and a red sun rises. Shapes loom across the water. How skillfully does the painter emulate the look of the “real thing”? Well, that seems less clear. Doesn’t the critic have a point? Isn’t the technique crude, the figures a mess? But wait. What is that momentous title? Impression, Sunrise. Monet is not really painting the harbor, or even the sun itself. He is painting an impression. But what does that mean?

To get it, we have to see visual textures that intervene between our eyes and the visual subject. Monet attempts to capture his subjective experience of the scene, including atmospheric conditions that may obscure the boat, the sea, and the harbor. Monet paints, not the water, but light defused through mist.

Impressionist technique …

Monet’s work is always sensitive to the conditions of vision, as we see in his series of over thirty versions of the same “subject”: the West Front of Rouen Cathedral. Atmospheric conditions, however, transform this identical subject into profoundly different experiences.

| Morning Light (1893) | Fog (1893) | Sunlight (1893) | Partial Sun (1894) |

Now, Monet was not innovating out of nothing. He was influenced, as were many artists of the day, by Japanese woodcut prints that always seemed to include weather conditions. Japanese prints still festoon the walls of Monet’s home at Giverny as they did in his day. Some of these prints came in series of views of the same object, inspiring the Rouen Cathedral series.

|

|

| Ando Hiroshige. (1858). 100 Views of Famous Places in Edo: Squall at Ohashi. Colored woodcut. | Claude Monet. (1899). White Water Lilies. Oil on canvas. |

Today, Monet is probably best known for his extensive series of paintings composed in his gardens at Giverny, Normandy. Each year, thousands visit his home, studio, flower gardens, and meticulously fashioned lagoons. Monet designed the grounds as an artistic composition in its own right. Flower beds are arranged according to the sequence of hues in the color wheel. Ponds and bridges emulate Japanese models. The canvases he painted there are among the most popular works in the world today. Tastes have changed since that first show!

You may well be comfortable with the White Water Lilies piece above. Still, don’t miss its departure from academic conventions. We are still looking through a window on the world. But the values of formal elements have changed. We don’t find meticulous drawing and modeling of the textures of flower and bridge. Instead, daubs of paint and clearly visible brushwork create complex and subtle interplays of light and color. The medium is emerging.

en Plein-air painting: Paul Cezanne

Artists associated with Impressionism shared a subversive agenda: “to undermine the authority of large, formal, highly finished paintings with historical, mythological, or religious subject‐matter, in favor of works that … expressed the artist’s response to the world (Impressionism 2004). Such a project is unlikely to be fulfilled in the studio.

en Plein-air Painting

Below, Paul Cézanne represents an artist at work in the plein-air. Some practical innovations in art equipment supported the move out of the studio. Already mixed paints were available in tubes, and canvas, easel, and brushes could be carried by hand in portable kits.

|

|

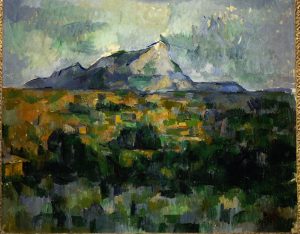

| A Painter at Work. (1875). Oil on Canvas. | (1906). Mont Sainte-Victoire. (1906). Oil on Canvas. |

Of course, artists had long worked on location. But the traditional method was to sketch preliminary studies before returning to the meticulous, time-consuming work of studio painting. Critics were appalled by the Impressionists’ apparently lazy decision to hastily improvise a painting on site in an hour or two. Meticulous Mimesis, Perspective, Foreshortening, and modelling of the subject all diminished in value. Forms were suggested with brief strokes. Subtle atmospheric conditions of color were captured with daubs of paint on the canvas. What mattered was color and light.

To the artists of the early 20th Century Avant garde—Matisse, Picasso, Seurat—Paul Cézanne was the great master who helped them re-see the possibilities of paint. Cézanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire is of course a landscape. But Cézanne has flattened out the illusion of distance, almost eliminating Linear Perspective entirely. Daubs of paint suggest trees, and mountains, but make little attempt to capture contours. Those splotches of paint fragment the image into semi-geometrical segments which, if we pay attention, detach into discreet elements of color. We’ll see below what Matisse and Picasso did with this conception of the role of paint.

Berthe Morisot

Often, discussions of Impressionism forget to mention women. With her sister Edma, Berthe Morisot received a “traditionally feminine education. Trained at home and with private tutors, her curriculum included drawing.” However, “in the mid‐nineteenth century respectable young ladies were not supposed to appear in public alone” or to become professional artists. Still …

The Morisot sisters faced a difficult choice and chose divergent paths. Edma married and reverted to a middle class lifestyle. Berthe chose to become …

Morisot’s treatment of the Harbor at Lorient displays the characteristics of Impressionist landscape. The linear perspective is traditional, but meticulous modeling is replaced by textures of paint rendering complex interplays of light and color.

|

|

| The Harbor at Lorient. (1869) Oil on Canvas. | The Cradle. (1872), Oil on Canvas. |

Higonet on Morisot’s The Cradle

Urban Realism: Edgar Degas

Another source of scandal was the Impressionist’s subject matter. Traditional European art generally chose “noble” subjects: religious themes, classical myths, and portraits of the social elite. Classical artists rarely tackled the lives of the working poor. In the late 19th Century, however, class consciousness stirred. Honoré Balzac and Emile Zola (a close friend of Cézanne’s since childhood) were writing novels of working life. And Impressionists, especially Edgar Degas, turned to the seedy bars and dance halls of the unrespectable demi-monde.

The Absinthe Drinker brought the spotlight of a great painter’s technique to an aspect of social life rarely depicted before. The figures are plain in appearance and plainly dressed, and they sit desultorily at their drinks, looking off into space and disconnected from each other. Still, daylight illuminates them openly, if not cheerfully, and there is no evidence of dissipation. By the way, do you see the compositional L figure defined by tables and back wall of the café? Do you see how those elements divide the image into zones cross cut by light?

|

|

|

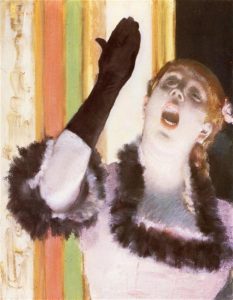

| In a Café (Absinthe Drinker). (1875 – 1876). Oil on Canvas. | Singer with a Glove. (1878). Pastel on canvas. | Dancer, Aged 14. (1878). Materials on wood. |

In the Singer with a Glove, Degas applies Impressionist fascination with interacting colors to his favorite subject: cabaret dancers. Notice, too, the cutting off of the image in the manner of a cropped snapshot. In later years, his eyesight failed and he began sculpting small figures, often dancers. Here, Degas captures the vulnerability and toughness of a young dancer. Look closely at her defiant stance and impassive face.

Post-Impressionism

Like many terms for “movements” in the arts, Impressionism is a fairly loose term. Although the innovative techniques associated with the movement transformed the possibilities for painting, Monet was really the only member of the group who remained consciously committed to Impressionist ideals throughout his career. Two painters who were heavily influenced by Impressionist techniques branched off in directions different enough to be labeled by a different term: Post-Impressionism.

Van Gogh

Born in the Netherlands, Vincent van Gogh famously sold very few paintings in his life despite having an art dealer for a brother. What he did do was paint. His father was a minister and van Gogh for a time studied theology, aspiring to the ministry. Beset by a crisis of faith, he …

Van Gogh’s early work reflected in a fairly dark style his concern for the working poor. Then, in February 1886 he moved to Paris to live with his brother the art dealer. Through Theo, Vincent met many of the leading Impressionists, Degas, Pissarro, Seurat, and Toulouse-Lautrec. Van Gogh’s time in Paris laid the foundation for a style which matured when he moved to Arles in Provence France. Dazzled by the quality of light in Provençal skies, his canvases exploded into life as his mental state deteriorated.

|

| Self-portrait with Bandage. (1889). Oil on canvas |

The self-portrait above shows bandages covering an ear which, during a manic episode, he lacerated with a razor. He was institutionalized for mental instability and eventually, during a time of enormous creativity, took his own life with a gunshot.

Monet painted impressions of scenes. By contrast, van Gogh was trying to express a vision arising from within. Van Gogh is not precisely identified with Expressionism, but the hypnotic force of his late work seems driven by internal forces. Line and form in The Church at Auvers are distorted, not by atmospheric conditions, but as an expression of inner turmoil.

|

|

|

| The Church at Auvers. (June 1890). Oil on canvas. | Wheatfield with Crows. (1890). Oil on canvas. | The Starry Night (Saint Rémy). (June 1889). Oil on canvas. |

The Wheatfield with Crows, part of a last outburst of activity just before his suicide, teems with menace. Notice the confident brush-strokes projecting rows of wheat in single bars of color and haunting the skies with birds dashed off in brisk, angled lines. The rapid technique of the Impressionist is expressing a personal vision dramatically interweaving the light of life with dark agents of doom.

The last is one of the world’s best loved paintings. Now, there is no substitute for standing in front of this work at The Museum of Modern Art in New York. Yet we can see a great deal in digital format. The formal elements are noteworthy: the pigment and brushstrokes. The compositional balance: a dark vertical shape on the lower left balanced by the luminous moon on the upper right. The dark values of cold, blue hues. The rhythm of repeated, swirling, organic whorls. And the painting pulses with the thematic contrasts. Cosmic chill hovers over the sleeping town and the looming, sepulchral tree. Yet the mind of the artist projects a whirling inner life onto churning skies and a cold moon is transformed into the life-giving, yellow light of the sun.

Paul Gauguin and the Primitive Ideal

Van Gogh moved to Provence for the magnificent light, and he tried to convince other artists to join him. Paul Gauguin, restless and disgusted by “civilization,” stayed with van Gogh for a time and then fled to the most “savage” place he could think of in the French Empire: Tahiti.

In the late 19th Century, Europe reached the high point of its colonial domination of the world. As do all oppressing peoples, Euro-Americans justified their exploitation of other peoples with a myth of cultural superiority. We dominate and enjoy privileges because our civilization is superior. They serve us because they are primitive and unfit for rule or independence.

However, a reaction against Euro-American colonialism was building. Over the next half century, the superiority of “civilization” began to be criticized. Gauguin was one of the artists who began to question mainstream European culture and to see virtue, even salvation in “primitivism.” In time, scholarship would lead to a discovery that “primitive” cultures are far from primitive, and Gauguin’s view of Tahiti was idealized and woefully misinformed. Nevertheless, his art began the process of finding value in despised cultures:

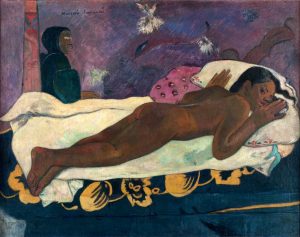

In these samples from his Tahitian paintings, Gauguin rejects the meticulous foreshortening, drawing, and linear perspective of academic art. Like Cézanne, he flattens the depth of his visual plane, as in the mattress on which the young girl lies. He replaces these areas of technique with masterful and complex interplays of subtle shades of color.

Thematically, Gauguin’s idealized view of a nobly “primitive” people expresses a half-conscious sense of the European observer’s moral ambivalence. Barbarian Tales depicts two young girls gazing impassively outward while a wretched European voyeur leers over their shoulders. Gauguin, who struggled to sustain marriage commitments, indulged in fairly predatory relations with young women in his “primitive” paradise (ironies intended!).

|

|

| Contes barbares (Barbarian Tales). (1902). Oil on canvas. | Spirit of the Dead Watching. (1892). Oil on canvas. |

Gauguin’s Spirit of the Dead Watching is rooted in the earth and in a half-grasped cultural tradition. The subject is the young woman Gauguin took temporarily for a wife. She is depicted on the bed, overlooked by birds and a spectral figure invoking the ancestors. But whose vision is this? The imagined vision of the European or that of the people he little understood?

References

Cezanne, P. (1875). A Painter at Work [Painting]. Private Collection. Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/paul-cezanne/a-painter-at-work-1875.

Cézanne, P. (1906). Mont Sainte-Victoire [Painting]. Zurich, Switzerland: private collection. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_1039789264.

Degas, E. (1875 – 1876). In a Café (Absinthe Drinker) [Painting]. Paris, France: Musée d’Orsay. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/SCALA_ARCHIVES_1039930252.

Degas, E. (1878) Singer with a Glove [Painting]. Cambridge, MA: Fogg Museum, Harvard University. Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/edgar-degas/singer-with-a-glove-1878.

Degas, E. (1878). Little Dancer Aged Fourteen [Sculpture]. Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art. ID 1999.80.28. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ANGAIG_10313951976.

Degas, Edgar [Article]. (2015). In I. Chilvers & J. Glaves-Smith (Ed.s), A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780191792229.001.0001/acref-9780191792229-e-681.

Expressionism. (2014). [Article]. Philip’s World Encyclopedia. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199546091.001.0001/acref-9780199546091-e-3976.

Gauguin, P. (1892). Spirit of the Dead Watching [Painting]. Buffalo, NY: Knox Art Gallery. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AWSS35953_35953_40438980.

Gauguin, P. (1902). Contes barbares (Barbarian Tales) [Painting]. Wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Paul_Gauguin_-_Contes_barbares_(1902).jpg.

Gauguin, P. (2004). [Article]. In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198604761.001.0001/acref-9780198604761-e-1369.

Gogh, V. (2004). [Article]. In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198604761.001.0001/acref-9780198604761-e-1462.

Higonet, A. (2008). Morisot, Berthe. In B. G. Smith (Ed.), The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195148909.001.0001/acref-9780195148909-e-717.

Hiroshige, A. (1858). One Hundred Views of Famous Places in Edo: Squall at Ohashi. [Woodcut]. https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822000632271.

Impressionism [Article]. (2015). In I. Chilvers & J. Glaves-Smith (Ed.s), A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780191792229.001.0001/acref-9780191792229-e-1255.

Matisse, H. (1909). La Danse (first version) [Painting]. New York City: The Museum of Modern Art. Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:La_danse_(I)_by_Matisse.jpg.

Matisse, H. (1948). Large Red Interior. Paris, France: Georges Pompidou Center. Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/henri-matisse/large-red-interior-1948.

Matisse, Henri [Article]. (2004). [Article]. Chilvers, I. (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198604761.001.0001/acref-9780198604761-e-2279.

Mondrian, P. (1930). Composition with Red, Blue, and Yellow. [Painting]. Zürich, Germany: Zürich Museum of Art. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_10310751326.

Mondrian, Piet [Article]. (2015). In I. Chilvers & J. Glaves-Smith (Ed.s), A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780191792229.001.0001/acref-9780191792229-e-1804.

Monet, C. (1893). The Cathedral at Rouen, in the Fog [Painting]. Paris, France: Musée d’Orsay. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_1039902689.

Monet, C. (1872). Impression, Sunrise [Painting]. Musée Marmottan. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_1039490324.

Monet, C. (1893). Rouen Cathedral, Effects of Morning Light [Painting]. Musée d’Orsay. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/SCALA_ARCHIVES_1039929321.

Monet, C. (1894). Rouen Cathedral: The Portal (Sunlight) [Painting]. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accession Number 30.95.250. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822000777712;prevRouteTS=1546717950567.

Monet, C. (1893). Rouen Cathedral, West Façade, Sunlight [Painting]. Washington, D.C.: The National Gallery of Art. Accession Number 1963.10.179. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ANGAIG_10313951608.

Monet, C. (1899). White Water Lilies [Painting]. Moscow, Russia: Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/SCALA_ARCHIVES_10313879002.

Morisot, B. (1869). The Harbor at Lorient [Painting]. Washington D.C.: National Gallery. Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/berthe-morisot/the-harbor-at-lorient.

Morisot, B. (1872). The Cradle [Painting].Paris: Musée D-Orsay. Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/berthe-morisot/the-cradle-1872.

Plein-air. (2010). [Article]. In M. Clarke & D. Clarke (Ed.), The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780199569922.001.0001/acref-9780199569922-e-1323.

Raguenet, J-B. (1763). A View of Paris from the Pont Neuf [Painting]. Los Angeles, CA: Getty Museum, ID 71.PA.26. http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/581/jean-baptiste-raguenet-a-view-of-paris-from-the-pont-neuf-french-1763/.

Rothko, M. (1964). No.5/No.22 [Painting]. New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art. Wikiart https://www.wikiart.org/en/mark-rothko/no-5-no-22.

van Gogh, V. (June 1890). The Church at Auvers [Painting]. Paris, France: Musée d’Orsay. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_1039490314.

van Gogh, V. (1889). Self-portrait with Bandage [Painting]. London, UK: Courauld Gallery. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_1039902132.

van Gogh, V. (June 1889). The Starry Night (Saint Rémy). [Painting]. New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art. ID 79802. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AMOMA_10312310534.

van Gogh, V. (1890). Wheatfield with Crows [Painting]. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Rijksmuseum. SID 18118473. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AIC_30038.

in European painting, the values and techniques developed out of the Renaissance: Linear Perspective, Foreshortening, Mimesis and the painting conceived as a Window on the World.

the methods and materials from which the work is forged, e.g. oil paint, mosaic, metric verse, prose narrative

the elements that form the basis of the language of art irrespective of any subject that may or may not be represented: line, color, form and shape, value, texture, space, and movement.

in visual art, the arrangement of visual elements for expressive and aesthetic impact: unity, proximity, similarity, variety and harmony, emphasis, rhythm, balance, etc.

art that follows explicit rules established by a tradition, institution, academy, or school. Sometimes dismissed by the avant-garde art world as overly cautious, derivative, or unoriginal

a late 19th Century dissident movement among French artists that challenged the conventions of academic art. Impressionists painted quickly, outside in the plein air, seeking to capture with a few deft strokes the colors, lighting and atmosphere of the scene—their subjective impression rather than the “real thing.”

a function or representational technique in visual art which imitates as closely as possible the appearance of nature, “the real thing.” Often contrasted with stylized techniques

in visual art, the illusion of 3-dimensional forms and spaces in 2-dimensional compositions, achieved by aligning and scaling forms to suggest depth and distance. Sometimes likened to seeing through a window

an illusion of depth created by contrasting the sizes of objects on the basis of how near or far they are from the eye of the viewer. E.g. a human figure in the foreground will be larger than a tall building in the distance.

in visual art, three-dimensional shapes or objects with height, width, and depth

a general term referring to innovative, experimental, potentially subversive artistic movements that challenge the conventions of the day.

the illusion of depth in a 2-dimensional image (e.g. a painting) in which lines angle toward a vanishing point

“half-world” or underground society of disreputable members of society often surreptitiously visited and patronized by aristocratic and middle class who maintained respectful public facades.

a loose term for the generation of artists, especially Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gaugin, who followed the Impressionists and carried their techniques forward

a style in art in which naturalism is replaced by exaggerated images to express intense, subjective emotion. Inspired by van Gogh, Gaugin, and Munch, the expressionist movement in painting was centered in Germany from about 1880 to 1905. Expressionism dominated early German cinema and Hollywood film noir in the 1930s (Expressionism).