Broken Love

Last week, we explored samples of art focusing on domestic and passionate love. Even today, audiences clamor for portraits of passionate amour (French for love). Passion promises a great deal. All too often, it leaves destruction in its wake. The arts of many cultures probe the distress left behind by passion’s betrayal. Consider this satirical portrait of a an apparently loving couple by Lucas Cranach the Elder. Notice the title. What is Cranach revealing to us? Notice the hands!

|

|

| Lukas Cranach, the elder. (1531). The Uneven Couple. Tempera on Beech. | Bernini. (1622-1624) of Daphne’s transformation. Marble. |

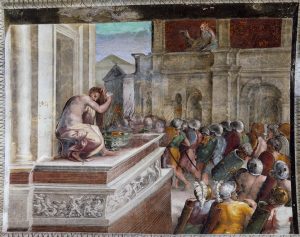

As we will see next week, the 14th Century Renaissance was driven by wide distribution in Europe of a rich trove of classical—Greek and Latin—learning preserved by Arabs and Orthodox monks. Patronized by private wealth, Renaissance artists began to focus their work on Greco-Roman myths. The trend became especially strong in the ensuing Baroque period. In the early 17th Century, the sculptor Gianlorenzo Bernini dramatized the climactic moment in a characteristically heart-breaking tale of passion’s destructiveness.

Ovid’s Metamorphoses

To make sense out of a great deal of post-Renaissance European art, one must know one’s classical myths, especially the Metamorphoses, in which the 1st Century Roman poet Ovid translated a range of tales from Greek myth. The word Metamorphosis means transformation, and the tales in the collection dramatize miraculous transformations. Their characters are beautiful mortals and quasi human, Greco-Roman gods and demi-gods driven by obsessive, destructive sexual passions.

In our selected tale, Phoebus, the Sun God, known to the Greeks as Apollo, is stricken with love for Daphne, a semi-divine naiad, or wood nymph. Things do not go well for the mortal woman trying to escape the desires of a powerful male force.

Ovid. (c 8 CE). The Metamorphoses. from The Tale of Daphne and Phoebus

Daphne, daughter of a River God was first beloved by Phoebus great God of glorious light. ‘Twas … out of Cupid’s[1] vengeful spite that she was fated to torment the lord of light.

For Phoebus … beheld that impish god of Love upon a time when he was bending his diminished bow, and voicing his contempt in anger said; “What, wanton boy, are mighty arms to thee, great weapons suited to the needs of war? The bow is only for … those large deities of heaven whose strength may deal mortal wounds to savage beasts of prey; and who courageous overcome their foes. …. Content thee with the flames thy torch enkindles … and leave to me the glory that is mine.”

Undaunted, Venus’s son replied, “O Phoebus, thou canst conquer all the world with thy strong bow and arrows, but with this small arrow I shall pierce thy vaunting breast!” … From his quiver he plucked arrows twain[2]: … one love exciting, one repelling love. The dart of love was glittering, gold and sharp; the other had a blunted tip of lead; and with that dull lead dart he shot the Nymph [Daphne], but with the keen point of the golden dart he pierced the bone … of the God.

Immediately the one with love was filled, the other … rejoiced in the deep shadow of the woods. … The virgin Phoebe … denied the love of man. Beloved and wooed she wandered silent paths, for never could her modesty endure the glance of man or listen to his love. Her grieving [River God] father spoke to her, “Alas, my daughter, I have wished a son in law, and now you owe a grandchild to the joy of my old age.” But Daphne only hung her head to hide her shame. The nuptial torch seemed criminal to her. … “My dearest father let me live a virgin always.” …

Phoebus when he saw her waxed distraught, and filled with wonder his sick fancy raised delusive hopes, and his own oracles deceived him.—As the stubble in the field flares up, … so was the bosom of the god consumed, and desire flamed in his stricken heart. …

Swift as the wind from his pursuing feet the virgin fled, and neither stopped nor heeded as he called; “O Nymph! O Daphne! I entreat thee stay, it is no enemy that follows thee. … I am not a churl—I am no mountain dweller of rude caves, nor clown compelled to watch the sheep and goats. … My immortal sire is Jupiter.[3] The present, past and future are through me in sacred oracles revealed to man, and from my harp the harmonies of sound are borrowed by their bards to praise the Gods.” …

The Nymph with timid footsteps fled from his approach, and left him to his murmurs and his pain. Lovely the virgin seemed as the soft wind exposed her limbs, and as the zephyrs fond fluttered amid her garments, and the breeze fanned lightly in her flowing hair. She seemed most lovely … and mad with love he followed … and silent hastened his increasing speed. As when the greyhound sees the frightened hare flit over the plain:—With eager nose outstretched, impetuous, he rushes on his prey, and gains upon her till he treads her feet, and almost fastens in her side his fangs. … So was it with the god and virgin: one with hope pursued, the other fled in fear. …

Her strength spent, pale and faint, with pleading eyes she gazed upon her father’s waves and prayed, “Help me my father, if thy flowing streams have virtue! Cover me, O mother Earth! Destroy the beauty that has injured me, or change the body that destroys my life.” Before her prayer was ended, torpor seized on all her body, and a thin bark closed around her gentle bosom, and her hair became as moving leaves; her arms were changed to waving branches, and her active feet as clinging roots were fastened to the ground— her face was hidden with encircling leaves.—

Phoebus admired and loved the graceful tree. … He clung to trunk and branch as though to twine his form with hers, and fondly kissed the wood that shrank from every kiss. … “Although thou canst not be my bride, thou shalt be called my chosen tree, and thy green leaves, O Laurel! shall forever crown my brows, be wreathed around my quiver and my lyre; Roman heroes shall be crowned with thee, … and as my youthful head is never shorn, so, shalt thou ever bear thy leaves unchanging to thy glory.”

Here the God, Phoebus Apollo, ended his lament, and unto him the Laurel bent her boughs, so lately fashioned; and it seemed to him her graceful nod gave answer to his love.

[1] Cupid: Roman name for the Greek god Eros, son of Venus (goddess of love, named Aphrodite by the Greeks). Cupid’s arrows compelled those struck by them to either love (gold for love; lead for hate). In the story, the powerful Phoebus derides the small bow of the diminutive Cupid, not understanding its power.

[2] Arrows twain: i.e. a pair of arrows

[3] Jupiter: Roman name for the Greek god Zeus, king of the gods on Mt. Olympus

So how shall we read the tale? On the one hand, it is a typical instance of an origin myth, in this case, the origin of laurel trees. On the other hand, it clearly dramatizes the all-too-human dynamics of passionate pursuit and evasion. Indeed, we could see it as an attempted rape, thwarted only by magic which essentially kills Daphne’s humanity. Can you see these dynamics in the relationships around you, or even in your own experience? Narrative traditions in many cultures explore themes of desire, loss, and the costs of failed love.

King David’s Lethal Passion

Last week, we saw David’s great glory in ascending to the throne of Israel. Under David’s leadership, the ancient Kingdom of Israel reached an unprecedented political prominence in the region. In the biblical accounts of his career, he is celebrated as a virtuous hero, a “man after God’s heart.” Many of the Psalms which lead the faithful in worship are attributed to him.

But David was also a great sinner. In the passage below, see David being led into genuine evil—lust, adultery, and murder—by the passion of a voyeur looking upon a woman’s body.

|

| Artemisia Gentileschi. (c.1640-5). David and Bathsheba. Oil on canvas. |

David’s Great Sin: 2nd Samuel, 11.2-12.24

Late one afternoon, when David rose from his couch and was walking about on the roof of the king’s house, that he saw from the roof a woman bathing; the woman was very beautiful. When David inquired about the woman, it was reported, “This is Bathsheba daughter of Eliam, the wife of Uriah the Hittite.” So David sent messengers to get her, and she came to him, and he lay with her. … The woman conceived; and she sent and told David, “I am pregnant.”

So David sent word to Joab, “Send me Uriah the Hittite.” And Joab sent Uriah to David. … David said to Uriah, “Go down to your house, and wash your feet.” Uriah went out of the king’s house …but slept at the entrance of the king’s house … and did not go to his house.

When they told David, “Uriah did not go down to his house,” David said to Uriah, “You have just come from a journey. Why did you not go down to your house?” Uriah said to David, “The ark and Israel and Judah remain in booths, and my lord Joab and the servants of my lord are camping in the open field; shall I then go to my house, to eat and to drink, and to lie with my wife? As you live, and as your soul lives, I will not do such a thing.”

Then David said to Uriah, “Remain here today also, and tomorrow I will send you back.” … The next day, David invited him to eat and drink in his presence and made him drunk; and in the evening he went out to lie on his couch, … but he did not go down to his house.

In the morning David wrote a letter to Joab: … “Set Uriah in the forefront of the hardest fighting, and then draw back from him, so that he may be struck down and die.” … The men of the city came out and fought and some of the servants of David … fell. Uriah the Hittite was killed as well. … When the wife of Uriah heard that her husband was dead, she made lamentation. When the mourning was over, David sent and brought her to his house, and she became his wife, and bore him a son.

As we know today, the sins of the great and powerful often go unpunished. But Uriah and Bathsheba had a champion—the prophet Nathan.

But the thing that David had done displeased the Lord, and the Lord sent [the prophet] Nathan to David. He came to him, and said to him,

There were two men in a certain city, the one rich and the other poor. The rich man had many flocks and herds; but the poor man had nothing but one little ewe lamb, which he had bought. He brought it up, and it grew up with him and with his children; it used to eat of his meager fare, and drink from his cup, and lie in his bosom, and it was like a daughter to him. Now there came a traveler to the rich man, and he was loath to take one of his own flock or herd to prepare for the wayfarer who had come to him, but he took the poor man’s lamb, and prepared that for the guest who had come to him.

Then David’s anger was greatly kindled against the man. He said to Nathan, “As the Lord lives, the man who has done this deserves to die; he shall restore the lamb fourfold, because he did this thing, and because he had no pity.”

Nathan said to David, “You are the man! Thus says the Lord, the God of Israel: I anointed you king over Israel, and I rescued you from the hand of Saul; I gave you your master’s house, and your master’s wives into your bosom, and gave you the house of Israel and of Judah; and if that had been too little, I would have added as much more. Why have you despised the word of the Lord, to do what is evil in his sight? …Now therefore the sword shall never depart from your house, for you have despised me, and have taken the wife of Uriah the Hittite to be your wife.

Thus says the Lord: I will raise up trouble against you from within your own house; and I will take your wives before your eyes, and give them to your neighbor, and he shall lie with your wives in the sight of the sun. For you did it secretly; but I will do this thing before all Israel, and before the sun.

David said to Nathan, “I have sinned against the Lord.” Nathan said to David, “Now the Lord has put away your sin; you shall not die. Nevertheless, because by this deed you have utterly scorned the Lord, the child that is born to you shall die.” …

The Lord struck the child that Uriah’s wife bore to David, and it became very ill. David therefore pleaded with God for the child; David fasted, and went in and lay all night on the ground. The elders of his house stood beside him, urging him to rise from the ground; but he would not, nor did he eat food with them. On the seventh day the child died. …

When David saw that his servants were whispering, he perceived that the child was dead; and David said to his servants, “Is the child dead?” They said, “He is dead.” Then David rose from the ground, washed, anointed himself, and changed clothes. He went into the house of the Lord, and worshiped.

David’s sin is great, but the repentance modeled in his penitential Psalm 51 has comforted and inspired sinners for centuries. The Psalm is also a masterful poetic expression. Can you trace those figures of speech we discussed last week: Anaphora and Parallelism?

King David. Psalm 51, a prayer of repentance

Have mercy on me, O God,

according to your steadfast love;

according to your abundant mercy

blot out my transgressions.

Wash me thoroughly from my iniquity,

and cleanse me from my sin.

For I know my transgressions,

and my sin is ever before me.

Against you, you alone, have I sinned,

and done what is evil in your sight,

so that you are justified in your sentence

and blameless when you pass judgment.

Indeed, I was born guilty,

a sinner when my mother conceived me.

You desire truth in the inward being;

therefore teach me wisdom in my heart.

Purge me with hyssop, and I shall be clean;

wash me, and I shall be whiter than snow.

Let me hear joy and gladness;

let the bones that you have crushed rejoice.

Hide your face from my sins,

and blot out all my iniquities.

Create in me a clean heart, O God,

and put a new and right spirit within me.

Do not cast me away from your presence,

and do not take your holy spirit from me.

Restore to me the joy of your salvation,

and sustain in me a willing spirit.

Then I will teach transgressors your ways,

and sinners will return to you.

Deliver me from bloodshed, O God,

O God of my salvation,

and my tongue will sing of your deliverance.

O Lord, open my lips,

and my mouth will declare your praise.

For you have no delight in sacrifice;

if I were to give a burnt offering, you would not be pleased.

The sacrifice acceptable to God is a broken spirit;

a broken and contrite heart, O God, you will not despise.

Torch Songs

It is difficult to empathize with the frustration felt by Ovid’s Phoebus lusting after Daphne or King David’s power play against a married woman. But the all too common outcome of passion, invoked over the centuries by many artists, is the heartbreak of unrequited love. Many of the great songs in the tradition of American popular music are Torch Songs:

Thematically, Yeats’ “Down by the Salley Gardens” works as a torch song. Scores of popular songs from the 20th Century qualify as torch songs, often sung by women: “Body and Soul,” “Stormy Weather,” “I Got it Bad (and that Ain’t Good),” “Can’t help Lovin’ Dat Man,” “Am I Blue” and many more. In “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,” a song from the 1933 musical Roberta, passion burns to smoke and ash.

Jerome Kern and Otto Harbach. (1933) “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes”

They asked me how I knew,

My true love was true,

Oh-oh-oh-oh, I, of course, replied,

“Something here inside,

Cannot be denied.”

They said, “Someday you’ll find,

All who love are blind.

Oh-oh-oh-oh, when your heart’s on fire,

You must realize,

Smoke gets in your eyes.”

So I chaffed them,

And I gaily laughed,

To think they could doubt my love.

Yet today, my love has flown away.

I am without my love.

Now, laughing friends deride,

Tears I cannot hide.

Oh-oh-oh-oh, so I smile and say,

“When a lovely flame dies,

Smoke gets in your eyes.”

Smoke gets in your eyes.

Listen to the great Sarah Vaughn’s performance of the song.

Torch songs maintain their appeal into more recent times. In 2011, Adele recorded a monster hit that poignantly captures the heartbreak and weary resolution of a left-behind lover encountering the lost beloved.

Adele and Dan Wilson, D. (2011). “Someone like You.”

I heard that you’re settled down

That you found a girl and you’re married now

I heard that your dreams came true

Guess she gave you things I didn’t give to you.

Old friend, why are you so shy?

It ain’t like you to hold back or hide from the lie

I hate to turn up out of the blue uninvited

But I couldn’t stay away, I couldn’t fight it

I hoped you’d see my face & that you’d be reminded

That for me, it isn’t over.

Never mind, I’ll find someone like you

I wish nothing but the best for you two

Don’t forget me, I beg, I remember you said:

“Sometimes it lasts in love but sometimes it hurts instead”

Sometimes it lasts in love but sometimes it hurts instead, yeah.

You’d know how the time flies

Only yesterday was the time of our lives

We were born and raised in a summery haze

Bound by the surprise of our glory days.

I hate to turn up out of the blue uninvited

But I couldn’t stay away, I couldn’t fight it

I hoped you’d see my face & that you’d be reminded

That for me, it isn’t over yet.

Never mind, I’ll find someone like you

I wish nothing but the best for you two

Don’t forget me, I beg, I remember you said:

“Sometimes it lasts in love but sometimes it hurts instead”, yay.

Nothing compares, no worries or cares

Regrets and mistakes they’re memories made

Who would have known how bittersweet this would taste?

Never mind, I’ll find someone like you

I wish nothing but the best for you two

Don’t forget me, I beg, I remembered you said:

“Sometimes it lasts in love but sometimes it hurts instead.”

Never mind, I’ll find someone like you

I wish nothing but the best for you two

Don’t forget me, I beg, I remembered you said:

“Sometimes it lasts in love but sometimes it hurts instead”

Sometimes it lasts in love but sometimes it hurts instead, yeah.

Note: the above link includes lyrics and the audio file.

It probably isn’t difficult to process the themes and dynamics of these two lyrics. Using our approach to poetry, we can read the plain sense of the words and fairly quickly determine who is speaking to whom. The first song reflects, perhaps inwardly, perhaps to an unidentified listener, the musings of one whose confident trust has been shattered. The second dramatizes an encounter between two one-time lovers, unnamed, but deftly realized.

About now, however, you should be in a position to track the poetic structures of the songs. Our old friends, Parallelism, Anaphora, and sheer poetic repetition are here. But notice also the Rhyme Scheme and Trimeter beats in “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes.” The patterns are looser in “Someone like You,” but don’t miss the occasional rhymes that provide thematic emphasis.

African American Heartbreak

The American songbook has been deeply influenced by African American musical and literary traditions. Early American folklore and songs blended Euro-American idioms with the rhythms of Africans forcibly imported as slaves. By the early 20th Century, African American music was beginning to establish an astonishing level of influence over all of American pop music. Not surprisingly, the music of a people enslaved and then denied full citizenship is full of heartbreak.

Singin’ Da Blues

African American musicians, as slaves and as “freedmen”[1] developed three traditions of startlingly innovative composition. “Negro spirituals” were sung in churches and on concert stages around the world. Jazz music was developed to entertain patrons of brothels and evolved into a transcendent form brilliantly wedding individual expression with mutually supportive partnership. And the Blues were sung to ease the breaking heart:

[1] Freedmen: the term used after the Civil War for slaves liberated by the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Blues: an African American folk song tradition that laments lost love or a hard way of life often due to the experience of social oppression. Often broken into 4-line stanzas with repetition and variation of lines.

E.g. “Oh, I asked her for water, oh, she brought me gasoline.//Oh, I asked her for water, oh, she brought me gasoline.//That’s the troublingest woman//That I ever seen” (Howlin’ Wolf, “I asked her for water” 1956).

The most pervasive traditions of American music today—rock and roll, rhythm and blues, reggae, hip hop, and many dimensions of contemporary country—descend at least in part from the blues.

Rick Darnell and Roy Hawkins (1969) “The Thrill is Gone”

The thrill is gone

The thrill is gone away

The thrill is gone baby

The thrill is gone away

You know you done me wrong baby

And you’ll be sorry someday

The thrill is gone

It’s gone away from me

The thrill is gone baby

The thrill is gone away from me

Although, I’ll still live on

But so lonely I’ll be

The thrill is gone

It’s gone away for good

The thrill is gone baby

It’s gone away for good

Someday I know I’ll be open armed baby

Just like I know a good man should

You know I’m free, free now baby

I’m free from your spell

Oh I’m free, free, free now

I’m free from your spell

And now that it’s all over

All I can do is wish you well.

Listen to the performance by the great B. B. King

Thematically, notice that the lamentation in this blues arises from the death of passion, the other side of passion’s coin. Initially, it seems so powerful in its promise of euphoria. But, it doesn’t seem to last. And as lovers learn generation after generation, it doesn’t offer much as a foundation for a lasting relationship. “The thrill is gone.”

Like Hebrew verse, a blues stanza uses repetition for emphasis, memory, and developing elucidation. Line 2 more or less repeats line 1. Line 3 takes things further. And line 4 resolves the tension. In this case, the stanza carries the repetition over 4 rather than 2 lines. Repeated blues lines linger like the throbbing pulses of heartbreak.

Ballad of Lost Love

Last week, we sampled the traditional English ballad, a story-song of a heart often broken by grief over a deceased lover. Anonymous folk ballads were sung and modified by countless bards over centuries. African American musicians developed their own ballad tradition, one steeped in violence to reflect the violent world Black people have long inhabited.

In 1899, a woman named Frankie Baker shot and killed her unfaithful lover, Allen Britt, in St. Louis. Within a year, the ballad “Frankie Killed Allen” had been composed by Bill Dooley and published by Hughie Cannon. More popularly titled “Frankie and Johnny,” the song has been sung by scores of artists and dramatized in several films. Thus, although there was an original publication, there is no authoritative version of the lyrics. All, however, share variants of the haunting refrain that speaks for millions of women in many ages and cultures: “He was my man, and he done me wrong.” The 1929 version by Mississippi John Hurt shines as an engaging example of Delta-style Blues. Here is Hurt’s version of the ballad.

Mississippi John Hurt (1928) “Frankie and Johnny”

Frankie and Johnny was sweethearts, O Lord how did they love.

Swore to be true to each other, true as the stars above.

He was her man, he wouldn’t do her wrong

Frankie went down to the corner, just for a bucket of beer.

She said “Mr. Bartender, has my lovin’ Johnny been here?

He’s my man, he wouldn’t do me wrong.”

“I don’t want to cause you no trouble, I ain’t gonna tell you no lie.

I saw your lover an hour ago with a girl named Nellie Bly.

He was your man, but he’s doin’ you wrong.”

Frankie looked over the transom, she saw to her surprise:

There on a cot sat Johnny, makin’ love to Nellie Bly.

“He’s my man, and he’s doin’ me wrong.”

Frankie drew back her kimona, she took out a little .44.

Rooty-toot-toot three times she shot right through that hardwood door.

Shot her man; he was doin’ her wrong.

“Bring out the rubber-tired buggies, bring out the rubber-tire hack.

I’m takin’ my man to the graveyard, but I ain’t gonna bring him back.

Lord, he was my man, and he done me wrong.”

“Bring out a thousand policemen, bring ’em around today.

Then lock me down in the dungeon cell and throw that key away.

I shot my man, he was doin’ me wrong.”

Frankie said to the warden, “What are they going to do?”

The warden said to Frankie “It’s electric chair for you,

‘Cause you shot your man, he was doin’ you wrong.”

This story has no moral, this story has no end.

This story just goes to show that there ain’t no good in men.

He was her man, and he done her wrong.

Listen to Mississippi John Hurt’s recording.

In 1955, Lena Horne recorded a highly produced and lushly orchestrated version of “Frankie and Johnny”: link. In this dramatized version, the vocalist takes up the Persona of Frankie, transforming the ballad into a Torch Song: “He was my man, but he done me wrong!”

The Spent Passions of Crazy Jane

In his later years, William Butler Yeats’ composed spare, hard-hitting verse that packed the punch of both disillusionment and wisdom, doubt and enduring hope. In 1932, Yeats published Words for Music Perhaps, exploring the link between literary verse and song lyrics. In that collection, he composed a series of poems expressing the jaded life view of Crazy Jane, a woman who has walked the path of life from passionate youth to sterile old age. “Crazy Jane and the Bishop” is no torch song. But it profoundly probes the bitter ashes of broken love.

William Butler Yeats. (1932). “Crazy Jane and the Bishop”

I met the Bishop on the road

And much said he and I.

`Those breasts are flat and fallen now

Those veins must soon be dry;

Live in a heavenly mansion,

Not in some foul sty.’

“Fair and foul are near of kin,

And fair needs foul,” I cried.

“My friends are gone, but that’s a truth

Nor grave nor bed denied,

Learned in bodily lowliness

And in the heart’s pride.

“A woman can be proud and stiff

When on love intent;

But Love has pitched his mansion in

The place of excrement;

For nothing can be sole or whole

That has not been rent.”

In her dialogue with the Bishop, Jane deals with the smug superiority of a religious prude who glories in her physical decay, chiding her for having trusted, so he thinks, the power of her physical beauty. But Jane knows that the world is more complex, more paradoxical than narrow, graceless piety will allow. Where does love “pitch his tent”?

Can you work out the Meter of Yeats’ poem? Yes, it’s Ballad Stanza, a meter Yeats returned to again and again. Notice how each Trimeter line deftly restates or explicates the concept in the previous Tetrameter line. The Rhyme Scheme also supports the poem’s themes. Stanzas are defined by an X-A-X-A-X-A pattern and the rhymes create suggestive contrasts:

- I … DRY … STY

- CRIED … deNIED … PRIDE

- inTENT … excreMENT … RENT (i.e. torn asunder)

What do you think of these rhymed patterns? Analyzing Meter and Rhyme Scheme may seem like a tedious pedantry. But when we begin to hear these rhythms, thematic patterns come alive.

References

Adele and Wilson, D. (2011). “Someone like You.” On 21. New York: Columbia Records. https://lyricstranslate.com/en/Adele-someone-you-lyrics.html

Bernini, G. (1622-1624). Apollo and Daphne [Sculpture]. Rome: Galleria Borghese. Retrieved from https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AIC_880017

Cranach, Lukas the elder. (1531). The Uneven Couple. [Painting]. Vienna: Museum of the Visual Arts. Retrieved from https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_1039789021

Horne, L. (1955). Frankie and Johnny. On It’s Love. New York: RCA Victor Records. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UVHNX8SUp30

Hurt, J. (1929). “Frankie and Johnny.” https://www.lyrics.com/lyric/27238655/Mississippi+John+Hurt

Hurt, J. (1929). “Frankie and Johnny.” [Audio Recording]. On Beyond Patina Jazz Masters. Beyond Patina Records. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VtxyjOFLXSg

Jerome, K. and Harbach, O. (1933) “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes.” In Roberta. https://www.lyricsplayground.com/alpha/songs/s/smokegetsinyoureyes.html

Ovid. Metamorphoses. (8 CE). Daphne and Phoebus [Apollo]. I.452-524. Trans. Brookes More. Boston: Cornhill Publishing Co. 1922. Retrieved from http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0028%3Abook%3D1%3Acard%3D452

Vaughn, S. (1958). “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes.” [Audio Recording]. On No Count Sarah. Em Arcy Records. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AybhBOqyQHQ

Yeats, William Butler. (1932). “Crazy Jane Talks with the Bishop.” In Words for Music, Perhaps. Retrieved from https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43295/crazy-jane-talks-with-the-bishop

an era in 15th and 16th century Europe marked by a Renaissance—or rebirth—of interest in and knowledge of classical Greek learning through humanist scholarship that challenged medieval values. In painting and sculpture, the work of artists in Italy, Germany, and the Low Countries which broke with Byzantine conventions to explore the geometry of perception and locate images and actions in time and space

organically rooted in a culture’s heritage, a connected web of narratives, rituals, and art that illuminate origins, map the world, and guide members of the culture in proper behavior and navigation of the environment

a figurative scheme that repeats the same word or phrase at the beginning of sentences or clauses: e.g. “I have a dream …” phrase repeated in Dr. Martin Luther King’s speech, (8/28/1963).

a figurative scheme which arranges phrases, clauses or sentences with the same syntactic or thematic forms: e.g. “We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender” (Winston Churchill, House of Commons address, 6/4/1940).

in English verse, a metrical pattern with 3 feet per line.

derived from the phrase to carry a torch for someone, a song lamenting the pain of lost love. Often a ballad which dramatizes the despair of a woman in thrall to a no-good man, though the gender roles can be reversed. The lamenting lover suffers from infidelity, neglect, or even violence.

a disciplined pattern of sound units throughout the lines of a poem. In English verse, meter is found in the number and pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables in a line. The most common English meter is the iamb: ta-Da-ta-Da-ta-Da-ta-Da//ta-Da-ta-Da-ta-Da.

a traditional, widespread metrical pattern common in ballads, nursery rhymes, and popular verse in which 4-line stanzas that alternate between 4 and 3 foot iambic feet: ta-Da-ta-Da-ta-Da-ta-Da// ta-Da-ta-Da-ta-Da

in English verse, a metrical pattern with 4 feet per line.

within a poem, a repeated pattern of sounds that end lines, define the boundaries of stanzas, and shape a poem’s themes. Designated for analysis by letters: a-b-a-b indicates rhymes in lines 1 and 3 and in lines 2 and 4. x-b-x-b indicates rhymes in lines 2 and 4, but not in lines 1 and 3.