The Renaissance Model of Art

So what is a painting? What do we expect it to do? Well, as we have seen, that depends on our cultural context. However, in Europe and the Americas, the model of painting that has descended from the Renaissance has been profoundly influential for a long, long time. Renaissance painters locked in on the moment of looking.

The overarching metaphor for Renaissance painting was that of a window on the world, emulating our vision of a moment in time and space. This sense of the canvas as a window was so strong that Renaissance painters began placing windows in the backgrounds of paintings set in interiors. We see this Convention , the Veduta, in Leonardo’s Madonna of the Creation. Behind the mother are windows opening onto a landscape with distant mountains.

|

|

|

| Madonna of the Carnation. ( 1478). Oil on canvas. | Piero della Francesca. (1470). Flagellation of Christ. Oil, tempera, panel. | Jan Vermeer. The Artist’s Studio. (1665). Oil on Canvas. |

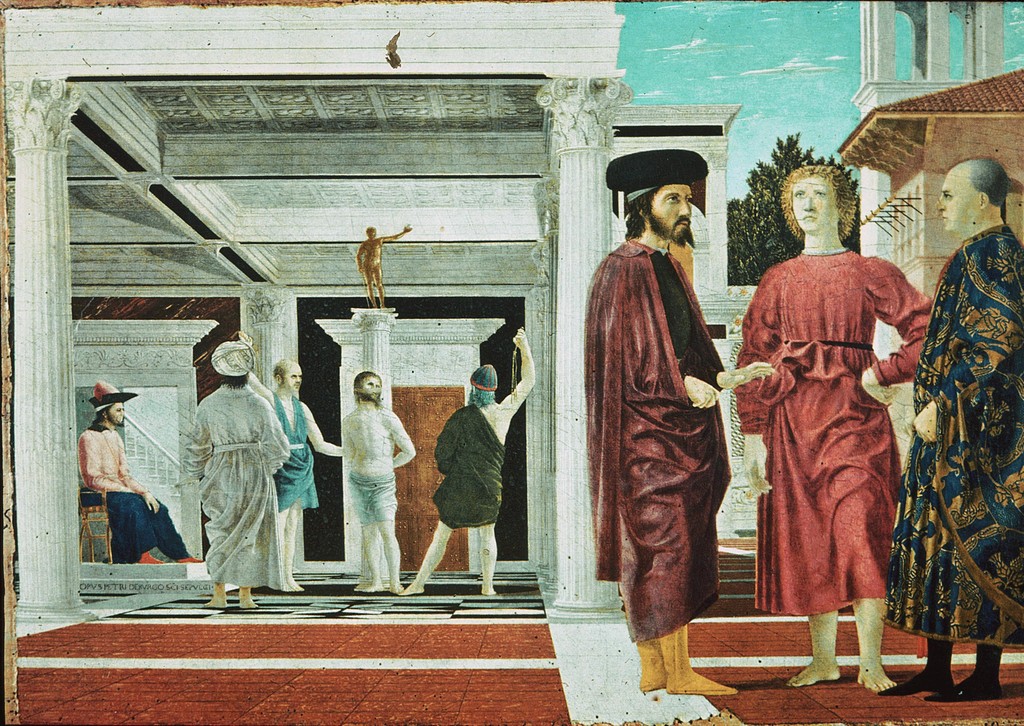

Piero della Francesca’s Flagellation[1] of Christ dramatizes a key moment from the gospels. But the work’s focus is on classical style and technique. Christ’s suffering is recessed and eclipsed in our awareness by sumptuous classical architecture and the elegant Greek column to which he is bound. Prominent Linear Perspective breaks a moment of vision down into zones of depth: foreground, middle distance, deep distance—precisely the concerns that challenge photographers today. The right half of the image is dominated by three contemporary, enigmatic men standing in the foreground, apparently disinterested in the drama.[2]

In his The Artist’s Studio, Vermeer takes things playfully much further. His composition doubles the act of visual Representation. The pictured artist–perhaps Vermeer himself–is at work capturing the image of a model on canvas. And the painting as a whole records that act of representation itself in the context of a studio divided into zones and instances of perception. The model gazes downward at fabrics on a table. The artist gazes at the model. A map covers the back wall, another example of visual representation.[5] And the actual canvas composes all with precise Linear Perspective delineated by in the tiles which define the depth of field.

Most remarkable is the painting’s frame perspective, our own vision of the room and its nested acts of vision and representation. In the foreground, curtains open on acts of vision and representation as if for spectators in a theater. Our viewpoint over the shoulder of the artist more or less approximates his view. Partially obscured by his body is the canvas on which his image is beginning to emerge. We see not only the acts of seeing and representation of the subjects, but our own role as spectators of art.

Through Vermeer, we explore the window-like framework of painting after the Renaissance painting: linear perspective, foreshortening, brushwork, light and shadow, and the Mimetic value of creating a “realistic” illusion of beholding the “real thing.”

[1] Flagellation: i.e. the whipping of Christ by Roman guards (Matthew 27.26).

[2] The identity and significance of the three men has been a topic of scholarly contention for a long time.

[3] The map has political and historical significance. It defiantly represents the Protestant provinces of the Netherlands during a time of conflict and war with the Catholic Holy Roman Empire.

Academic Art

Renaissance artistic conventions proved to be astonishingly durable. By the 19th Century, Classical and Renaissance models of art dominated standards of taste in the Euro-American art world. National academies, or associations of artists such as the Académie des Beaux-Artes in France codified rules for composition and used them to judge the works submitted for inclusion in their authorized shows. An artist whose work was shown by the Académie could count on large commissions from people of wealth and social standing who wished to prove their taste in purchasing paintings and sculpture.

These standards heavily influenced the public in what to expect from “good” painting. The result was a powerfully authoritative set of standards that governed artists’ techniques and public taste:

Academic Art

art that follows explicit rules established by a tradition, institution, academy, or school. Sometimes dismissed by the avant-garde art world as overly cautious, derivative, or unoriginal

The rules for Academic Art derived from the Renaissance model of painting and its values:

- Preference for noble subjects that affirm social values

- The painting as a window on the world

- Naturalistic representation as the goal of art

- Technical prowess in linear perspective, foreshortening, and modelling

- Studio production, studied composition and meticulously worked oil paint

- Painstaking brushwork that disappears into the represented image

Jacques-Louis David’s Oath of the Horatii exemplifies Neo-classical Academic Art of the 19th Century. The subject matter is noble: a legendary moment from the Roman past of civic duty as a lesson for 18th Century France. Technically, the Linear Perspective is perfectly laid out. The lighting is carefully controlled to highlight the men thirsting for glory and the women anticipating grief. The figures are perfectly modelled and the action—Greek Rhythmos—rendered dynamically. The raised arms form an rising triangle balanced by a slumping triangle of despairing women.

|

| David, Jacques-Louis. (1784). The Oath of the Horatii. Oil on canvas. |

Now, every classicism breeds a reaction. Notice that the contemporary definition of Academic Art above reflects a dismissive view of “art that is conservative and lacking in originality.” As we will see next week, powerful revolutions against Academic Art arose in the late 19th Century. For perhaps 150 years, the professional art world has come to value individual creativity, innovation, and the deconstruction of the image. Conventional and commercial artists are often marginalized and dismissed.

Yet the Renaissance model lives on in popular, mainstream tastes and preferences. Even today, many viewers are put off and confused by the innovations and experiments of the so-called “Modern” period, and instinctively revert to the familiar and comprehensible conventions of Leonardo, Raphael, Michelangelo, and others. The Renaissance is not technically a Classical era, but it channeled the Greeks and Romans and endures today as a Classic approach that is hard to shake off.

References

David, Jacques-Louis. (1784). The Oath of the Horatii. [Painting]. Paris: muse du Louvre, ID ART147619. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARMNIG_10313257933.

Francesca, P. d. (c.1455-60). Flagellation of Christ [Painting]. Urbino, Italy: Palazzo Ducale. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822001048873.

Langdon, A. (2001). Caravaggio. In H. Brigstocke (Ed.), The Oxford Companion to Western Art. Oxford University Press,. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780198662037.001.0001/acref-9780198662037-e-464.

Leonardo da Vinci (circa 1478). Madonna of the Carnation [Painting]. Munich: Alte Pinakothek. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/SCALA_ARCHIVES_1039779325.

Vermeer, J. (ca. 1660). The Artist’s Studio [Painting]. Vienna, Austria: Art History Museum. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/#/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822000703502.

an era in 15th and 16th century Europe marked by a Renaissance—or rebirth—of interest in and knowledge of classical Greek learning through humanist scholarship that challenged medieval values. In painting and sculpture, the work of artists in Italy, Germany, and the Low Countries which broke with Byzantine conventions to explore the geometry of perception and locate images and actions in time and space

a characteristic feature—subject matter, theme, technique, style—that defines a genre or artistic tradition and is expected and understood by the audience in its context

(Italian: view) a visual composition located in a recognizable landscape. During the Renaissance, often an interior scene with a background window looking out on an identifiable landscape.

the illusion of depth in a 2-dimensional image (e.g. a painting) in which lines angle toward a vanishing point

a function of visual art which seeks to depict a visual subject that viewers will recognize from a theoretical “real world.” Opposite: abstract or non-figurative art

an illusion of depth created by contrasting the sizes of objects on the basis of how near or far they are from the eye of the viewer. E.g. a human figure in the foreground will be larger than a tall building in the distance.

in visual art, the quality of imitating as closely as possible the appearance of nature, “the real thing." Often contrasted with stylized technique

in the Euro-American tradition, a reference to the works, styles, and themes of Greek and Roman antiquity. More generally, an aesthetic valuing clarity, order, balance, unity, symmetry, and dignity, usually honoring a cultural tradition associated with some golden age of the past.

A national association of artists in France that, in the late 19th Century, maintained a firm grip on the conventions and styles deemed fashionable for patronage by French art lovers. The Académie gave shows of artists that it endorsed, making or breaking careers of artists. The Impressionists began as a group of Académie rejects holding their own individual show.

art that follows explicit rules established by a tradition, institution, academy, or school. Sometimes dismissed by the avant-garde art world as overly cautious, derivative, or unoriginal

in classical Greek art, the illusion of dynamic action in a stationary image through mimetic of a body's patterns of motion during the performance of an action

A) an exemplar of excellence in a particular genre or tradition; B) an aesthetic that features clarity, order, balance, symmetry, reason, mathematical precision; C) the ancient tradition of art, literature, and philosophy from classical Greece and Rome