Classical Culture in Greece

Catalogues of colleges and universities traditionally listed Classics as a course of study. In the European educational tradition, Classics referred to ancient Greece and Rome: their languages, histories, literatures, and arts which permeate “Western” culture. Euro-American cultures were exported from Europe, which developed from vestigial Roman culture preserved in the Roman Catholic Church. Roman culture itself was shaped by the influence of Greek mercantile colonies. All Western cultural roads lead back to Greece.

Greek Art: Archaic Period

Surrounded by the Mediterranean, Greeks took to the sea, cultivating trading relationships with nearby peoples. From the Phoenicians, Greeks learned maritime trade techniques and how to write with a phonetic alphabet. Greek culture was especially influenced by the sophisticated culture of the Nile, Egyptian myths, thought, technology, and art.

| Kouros figure. (6th C. BCE). Attributed to Myron | Kore figure, Lady of Auxerre. (c. 630 BCE). Incised limestone, originally painted. |

We can see the impact of Egypt in the artistic styles of what scholars call Greek’s Archaic era. Votive figures from this time are clearly influenced by Egyptian models. Notice how the Kouros and Kore figures emulate Egyptian statuary: the timeless stance, the abstract, stylized features, and the vacant smiles. In the hair and fixed smile of these figures, we also see the influence of Mesopotamian cultures. (No time here for a close look at Assyrian and Babylonian art!)

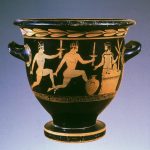

Then Greek artists began to innovate. Vases and Amphorae of the 6th and 5th Centuries depicted scenes from daily life and heroic athletes and warriors. Remarkably, the figures are depicted in motion. Greek art was coming alive.

|

|

| Diosphos Painter (c. 500 B.C.), Black-figure amphora (jar) | Peleus Painter. (c.430BCE) Red-figure pottery: Bell-Krater with Torch-racers and Priest at Altar |

- Red Figure Vases: an innovative style of pottery from ancient Greece (6th C BCE) in which the background is painted black, leaving figures in the unpainted spaces the red color of the pottery.

- Black Figure Vases: an innovative style of pottery in ancient Greece (7th C BCE) in which figures were incised and painted in black silhouette on light red clay.

It may not seem remarkable today, but the fact that those black and red figure potters depicted action marked a profound change in artistic possibilities. These figures began to challenge viewers in a new way, forcing them to consider visual experience itself.

The Classical Period

In the 5th and 4th Centuries, Greek dominance over the Mediterranean reached its peak. Trade colonies were established across the Mediterranean: Asia Minor, North Africa, Italy, southern France, and Spain. Beyond economic and political dominance, Greek culture achieved an almost unprecedented level of influence. Rome, for example, emulated Greek culture as it began to develop its power base. The entire Mediterranean world was dazzled by astonishing achievements in philosophy, medicine, geography, history, mathematics, democracy and the arts that shaped the Western world.

|

| Map of Greek and Phoenician trading settlements in the Mediterranean |

Now, “Greece” at the time was far from one fused entity. Ancient Greek culture was defined by a shared tradition of language and myth. Barbarians were those who spoke no Greek, despised by Greek speakers for growling bar, bar, bar, bar. Greek-speaking peoples clustered in city states, each polis competing with and sometimes warring with one another. Among these city states the polis of Athens reached a so-called “Golden Age” under the leadership of Pericles. Athens boasted magnificent architecture, especially on the Acropolis. The Parthenon, a temple to Athena, Goddess of wisdom and patroness of the city, was a triumph of order and harmony. It also achieved a technological breakthrough for the day: roof trusses spanned much wider spaces between pillars than did those of Egyptian temples.

|

|

| Acropolis, general view. Athens, Greece | Parthenon. (447-436 B.C). Exterior, west end. Athens, Greece (Acropolis) |

What do you see in the Parthenon? The columns? The pediment, that gable spanning the tops of the columns? Where have you seen these before? In the White House. The Securities and Exchange building on Wall Street. Neo-classical homes in your neighborhood. Inspiring architects into our own day, the look of the Parthenon well earns the term Classical.

On a smaller scale, Greek artists innovated exciting new forms in painting and sculpture. Sadly, apart from a few remarkable sculptures, few of these pieces have survived the erosion of time. Their reputations and theories, however, have endured.

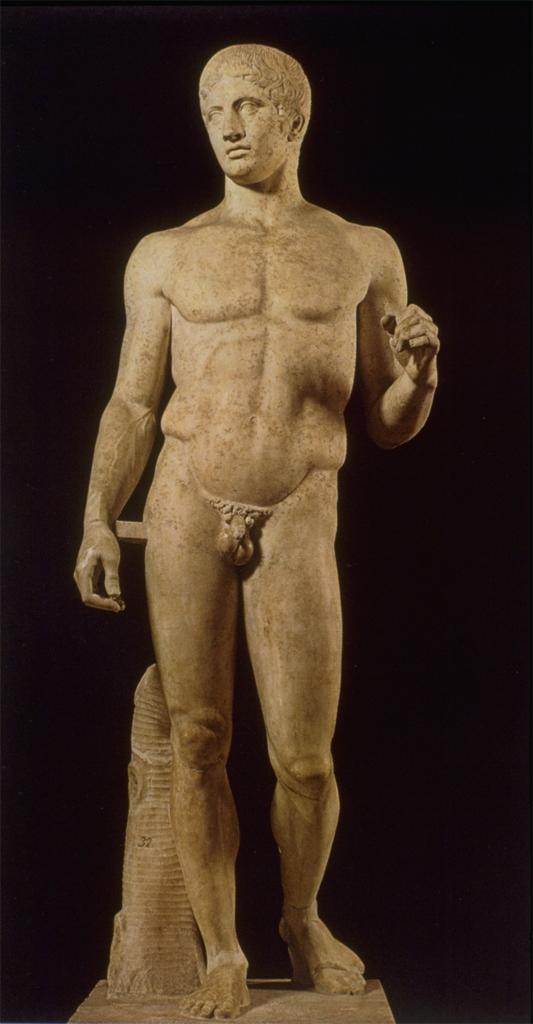

Mimesis refers to the imitation of nature. In the sculptures below, we see unprecedented levels of anatomical precision in presenting the structures of the human body. Greek philosophers and historians were fascinated by empirical observation. Greek sculpture reflects that orientation in its meticulous attention to the form and movement of muscles, skin, and bones. Consider the mimetic naturalism of the musculature depicted in the Spear Carrier (Doryphoros). But consider as well the figure’s stance and its suggestion of movement:

|

|

| Doryphoros [Spear Bearer]. (ca. 450-440 B.C.E.). Roman marble copy of original bronze | Diskobolos [Discus Thrower]. (Bronze original c. 450 BCE; marble copy c. 2nd century CE) |

In classical sculpture, figures come vitally alive. Precisely modeled human forms suggest movement in time and express moods and attitudes.

Let’s see. Mimetic precision. Does that mean portraiture? Well, no. Classical art sought to depict, not a human being but the human being. Theirs was an art not of the real but of the Ideal: “Classical sculpture is idealized, utilizing systems of proportions, balance, and expression that bring order, serenity, and completeness to the figure” (Silberman, Stansbury-O’Donnell, Rhodes).

We use the word ideal pretty casually. In ancient Greece, the term derived directly from the work of Plato, a philosopher of incalculable influence. The ideal is …

Classical sculptural figures were formulated to reflect the ideal articulated by the philosopher Socrates in the dialogues of his student, Plato. “Platonic idealism” holds that real objects—a basket, a wagon, a horse, a man—are imperfect reflections of an ideal form beyond our experience: the perfect basket, wagon, horse, man. Classical Greek artists meticulously represented human anatomy, but they sought an ideal beauty beyond ordinary mortals: purity of line, balance, harmony, proportion.

The figure of the Spear Carrier above is perfectly proportioned according to precisely calculated formulas of beauty: facial features, skeletal structure, musculature, etc. This ideal appearance continues to influence our idea of personal beauty even today, sometimes to the detriment of people’s self-image and mental health.

The Spear Carrier is also, as I am sure you have noticed, nude. Attitudes of the Greeks toward the body differed from those of neighboring cultures. A key building in every polis was a palaestra, that is, a gym. Athletic workouts and competitions (e.g. the Olympics) were always performed in the nude. When a palaestra was established in a conquered city, the nudity often offended the conquered people. This was one of the reasons for the Jewish Maccabean Revolt (2nd Century BCE) revolt against Seleucid (Greek) rule.

Hellenistic Art

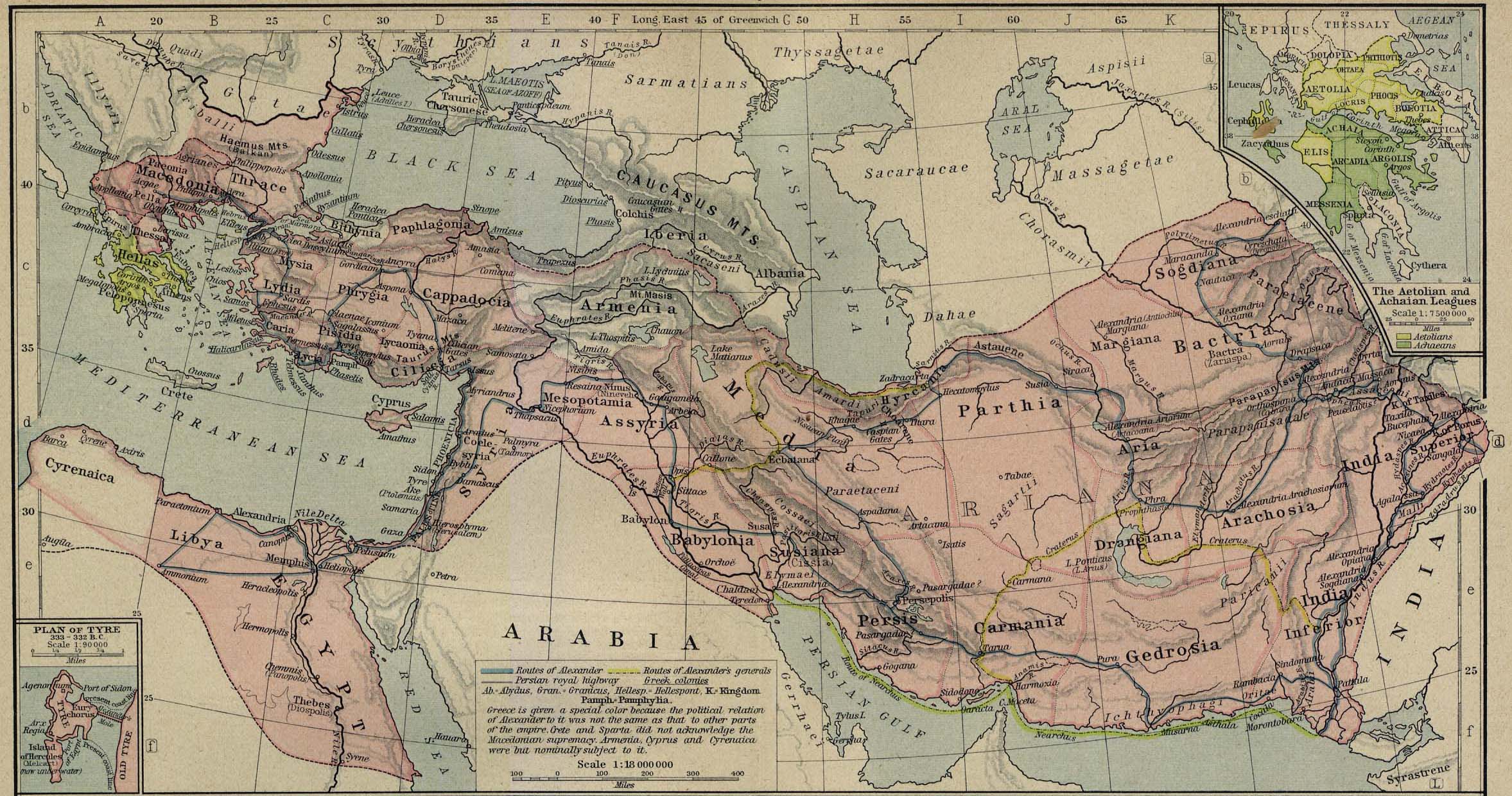

In the 4th Century BCE, the Macedonian/Greek king Alexander the Great avenged Greek peoples for earlier, failed invasions by the Persians and went on to conquer Asia Minor, Palestine, Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia, and parts of India. After his death, Alexander’s authority splintered into regional dynasties: Ptolemaic Egypt and Seleucid Asia Minor, including the Palestine of the New Testament. Hellenistic Greek culture spread from India to North Africa.

|

| Map of Alexander’s Macedonian (Greek) Empire at its greatest extent, bout 336 BCE. |

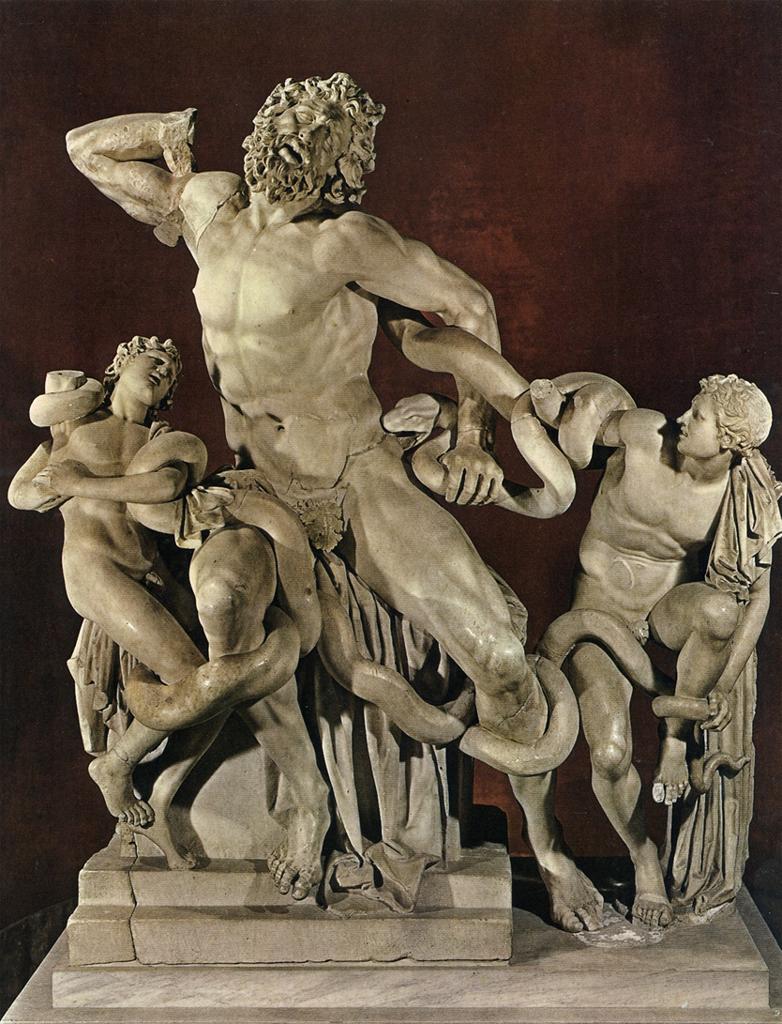

The traditional distinction between Classical and Hellenistic art is controversial. (Scholars always argue over eras and movements.) Still, enhanced techniques in Hellenistic art master folds of fabric, emotions, and individuality.

Nike: the Personification of Victory

|

|

|

| Nike of Samothrace. (3rd-2nd Century BCE). Marble. | Venus de Milo. (c. 100 BCE). Frontal view. | Laocoön. (50-25 BCE). Marble |

The figure of a half nude Venus discovered in 1820 on the Greek island of Melios (Milos) is one of the most famous images of art on earth. One of very few Greek originals to survive, it is dated today to the 1st Century B.C.E.

The Venus de Milo

[5] As you will recall, an aesthetic perspective responds to formal aspects of design and sets aside ulterior motives such as, in this case, erotic impulses. Of course, aesthetic perspectives can be hard to maintain and can conflict with some ethical values.

Hellenistic art draws on classical conventions, but adds a taste for naturalism, i.e. depiction of the specific features of individuals, as well as a deeper embrace of drama and emotion.

We see this in the powerful Laocoön: “A spectacular antique marble group (Vatican Mus.) representing the Trojan priest Laocoön and his two sons being crushed to death by sea serpents as a divine punishment for warning the Trojans against the wooden horse of the Greeks” (Laocoön).[6] The Laocoön‘s intense emotionalism [was] influential on Baroque sculpture, and in the Neoclassical age … [was seen] by Winckelmann,[7] as a supreme symbol of the moral dignity of the tragic hero and the most complete exemplification of the “noble simplicity and calm grandeur” that he regarded as the essence of Greek art and the key to true beauty (Laocoön).

[6] The subject matter of Laocoön testifies to the complexity of Greco-Roman cultures. The story of Laocoön is told in the Aeneid, an epic narrative grafted by the Roman poet Virgil onto Homer’s Greek epic the Iliad. Homer sings of the Greek heroes who conquered the city of Troy. Virgil tells of a Trojan warrior who survives the war and goes on an epic journey leading to the founding of Rome. The poem coopts Greek myth to infuse Rome’s origin story in Greek tradition.

[7]Winckelmann: Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768) was a “German art historian and archaeologist, a key figure in the Neoclassical movement and in the development of art history as an intellectual discipline” (Winckelmann).

References

Diosphos Painter, attributed to. (ca. 500 B.C.). Terracotta neck-amphora (jar). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/SS7731421_7731421_11663258

Dipylon Vase. (8th century B.C.E.). Large funerary krater with scenes of ritual mourning (prothesis) and funeral procession of chariots. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AIC_960032

Diskobolos [Discus Thrower]. (Bronze original c. 450 BCE; marble copy circa 2nd century CE). Roman copy of a work by Myron. Rome, Italy: National Museum. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/SCALA_ARCHIVES_10310840518

Doryphoros [Spear Bearer]. (ca. 450-440 B.C.E.). Roman marble copy after the original bronze figure. [Sculpture]. Naples, Italy: Museo Archeologico Nazionale. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AIC_970018

Holberton. P. (2001). “Classicism.” In H. Brigstocke (Ed.), The Oxford Companion to Western Art. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198662037.001.0001/acref-9780198662037-e-563

Ideal. (2004). [Article]. In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780191782763.001.0001/acref-9780191782763-e-1192

Kore figure, known as Lady of Auxerre [Sculpture]. (c. 640-630 BCE). Musée du Louvre. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_10311440843

Kouros figure. Attributed to Myron. [Sculpture]. (6th century BCE). Greece: National Museum of Archaeology. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/LESSING_ART_1039490474

Greek and Phoenician Settlements in the Mediterranean, 550 BCE [Map]. (1911). In Shepherd, W. R. The Historical Atlas. https://legacy.lib.utexas.edu/maps/historical/shepherd/greek_phoenician_550.jpg

Laocoön. (2003). [Article]. In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press,. https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bethel.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780191782763.001.0001/acref-9780191782763-e-1343?rskey=y59HDq&result=2

Laocoön. (50-25 BCE). [Sculpture]. Vatican: Vatican Museum. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/AWSS35953_35953_31685601

Macedonian Empire, about 323 BCE [Map]. (1911). In Shepherd, W. R. The Historical Atlas. https://legacy.lib.utexas.edu/maps/historical/shepherd/macedonian_empire_336_323.jpg

Osborne, R. (1998) Archaic and Classical Greek Art. New York: Oxford University Press. (Not web accessible).

Parthenon. (447-436 B.C). Exterior, west end. Athens (Acropolis). ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822003526546

Peleus Painter. (c.430-20 B.C). Bell-Krater: Two Torch-racers and Priest at Altar [Vase]. Boston: Arthur M. Sackler Museum. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822003065750

Rhodes, F. R. (2012). Greek Art and Architecture, Classical. In N. Silberman (Ed.), The Oxford Companion To Archaeology. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 Dec. 2019, from https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199735785.001.0001/acref-9780199735785-e-0171

Venus de Milo. (c. 100 BCE). Frontal view. [Sculpture]. Paris, France: Musée du Louvre. ARTstor https://library-artstor-org.ezproxy.bethel.edu/asset/ARMNIG_10313261734

Venus de Milo [Article]. (2004). In I. Chilvers (Ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198604761.001.0001/acref-9780198604761-e-3625

a function of art offered as a gift to honor a god or used within a worship ritual

in Archaic (pre-Classical) Greek art, heavily stylized votive human figures—Kouros (male) and Kore (female)—influenced by classical Egyptian statuary, with static, timeless poses, abstracted features, and limited anatomical precision

Ceramic vessels with pointed bottoms used to transport grain and liquids, especially wine

in the Euro-American tradition, a reference to the works, styles, and themes of Greek and Roman antiquity. More generally, an aesthetic valuing clarity, order, balance, unity, symmetry, and dignity, usually honoring a cultural tradition associated with some golden age of the past.

a function or representational technique in visual art which imitates as closely as possible the appearance of nature, “the real thing.” Often contrasted with stylized techniques

(Italian for counterpoise) in Classical Greek sculpture, the dynamic representation of a human body standing as people actually stand, a complex balance of weight unevenly distributed between the legs

in classical Greek art, the illusion of dynamic action in a stationary image through mimetic of a body's patterns of motion during the performance of an action

in visual art, the quality of imitating as closely as possible the appearance of nature, “the real thing." Often contrasted with stylized technique

in the classical tradition of ancient Greece, a doctrine articulated by Plato in which flawed, observable objects suggest perfect exemplars in an inaccessible realm—the ideal horse, the ideal basket, etc. In classical Greek art, a precise (mimetic) imitation of, say, a human body adjusted to suggest the ideal through perfectly balanced order, proportion, and elegance

the Greek term for emotion. In ancient Greek art, the emulation of human emotion and experience within the appearance of human figures.