5 Publish and Perish?

Publish or perish is typically associated with research universities where professors are tenured only if they produce reputable scholarship. To be sure, some write a book, attain a position for life, and then die on the vine. The phrase seemingly did not apply at Concordia. Yet Dean Carl Bailey had worked since the Fifties to elevate academic quality by recruiting more teachers with doctorates. He instituted degree-completion leaves, a travel fund to further attendance at regional or national meetings, and “contributions to field” as a Faculty Handbook criterion for deciding tenure. His efforts boosted advanced degrees holders from 20 percent in 1959 to 39 percent in 1970 alarmed some the college might be secularized and lose its Lutheran identity. While President Knutson acknowledged piety could not substitute for academic ability, he insisted faculty must show Christian sympathies. Conversations about the proper balance between intellect and faith continued as more professors conducted research and the number with doctorates rose to 70 percent. In my case, I took up publishing after a decade of teaching at Concordia and, arguably, still perished professionally.

Dean Bailey helped blaze a path by conducting atomic energy experiments with an ion accelerator in the physics department every Friday afternoon. Paul J. Christiansen attained an international reputation as a choral director and composer. Philosopher Reidar Thomte won Guggenheim and Fulbright grants to research and publish a book about Danish theologian Sören Kierkegaard. Olin Storvick’s archeological work became part of the traveling Smithsonian Institution exhibit, “King Herod’s Dream: Caesarea on the Sea.” Historian Hiram Drache published several volumes on American agricultural history. Daryl Ostercamp, winner of a Fulbright professorship in Iraq and a National Science Fellowship at the University of East Anglia, published in Chemistry journals. Peers honored Gerald Heuer’s scholarship by choosing him to coach America’s International Math Olympiad team, which finished fifth after China, Romania, USSR, and East Germany. In 1976, Heuer designed Concordia’s sabbatical program in which faculty might take one- or two-semester leaves every seventh year for professional study.

I had no intention of publishing until hard-nosed Dean Gerald Hartdagen rated me lower for promotion than a less-able teacher who had done some research. When distinguished Southern historian Dewey Grantham offered a one-year National Endowment for Humanities Seminar on 20th Century United States Society at Vanderbilt University, I proposed a book-length study of American liberal intellectuals John Dewey, Walter Lippmann, Reinhold Niebuhr, Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., John Kenneth Galbraith, and Paul Goodman. I had written a master’s length essay on Niebuhr and a seminar paper on Lippmann, researched Dewey for my dissertation, and read many books by Galbraith, Goodman, and Schlesinger. To study the intellectual links, ideological differences, and societal impacts of these preeminent thinkers afforded me an exciting prospect. Alas! I was named an alternate, a meaningless honor because few declined. Yet my attempt impressed Hartdagen who finagled me a yearlong sabbatical at 60 percent salary. I welcomed the reprieve after ten intense years preparing and teaching a dozen new courses. My family survived the cut in pay because the children were in primary school and Jo had resumed working as part-time secretary for the Sociology – Social Work Department. She was conveniently located just down the hall from my office on the Third Floor of recently remodeled Old Main. We walked together to and from work for the next quarter century.

Learning the Historian’s Craft

With a possible book on liberal intellectuals in mind, I spent my yearlong sabbatical researching Schlesinger’s triple career as prize-winning historian, Democratic Party activist, and well-known pundit. While his facile prose made the work pleasurable, his prodigious output and ability to write faster than I could read complicated my task. Nonetheless, while I prepared a fifty-page article and subsequently submitted it to the American Quarterly for publication (or rejection as it turned out), I also salvaged something from my dissertation on citizenship and Iowa common schools by preparing an article about religious instruction in supposedly secular institutions. Despite my good intentions of continuing this work after returning to the classroom, I soon shelved scholarship. The time demands of three courses and more than one hundred students every semester as well as a wife and two growing daughters dictated limiting research and writing to summer “vacations.”

Still, I had drafts of two articles available when fellow Stow Persons student Hamilton Cravens contacted me about contributing to a festschrift for our graduate school mentor. Cravens, an overly loquacious self- promoter, had always irritated me. Still, I was not about to let personal dislike come between a possible publication and me. I submitted both the Schlesinger and civic religion essays for his consideration. Ham rejected the former as too political and selected the latter for the book. His Iowa State University colleague Richard Lowitt liked the Schlesinger piece and suggested submitting it to the New York Review of Books or the South Atlantic Quarterly. For the next two years, Cravens kept me on task and offered oleaginous buckets of encouragement. His instrumental role in shaping my earliest published work exemplified a colleague’s wisdom when he remarked: “You don’t need to love someone like a brother to work with him.”

Professor Lowitt’s praise motivated me to resubmit the Schlesinger article. As an avid reader of “the New York review of each other’s books,” I thought the journal unlikely to accept anything authored by an unknown from flyover country. So, I tried the South Atlantic Quarterly. Being put into print by Duke University Press seemed plenty prestigious to me. When my essay appeared shortly before my 40th birthday in 1981, it even merited a reply by the great man himself, which probably attracted readers and ensured them overlooking what I had written.

Schlesinger’s arguments in The Vital Center: The Politics of Freedom (1949) made him “a man in the middle.” The collapse of capitalism in the Great Depression, the excesses of messianic ideologies, and fifty million dead in the Second World War, he claimed, necessitated the reconstruction of liberalism so it could defend freedom from the extremist ideologies of Fascism and Stalinist Communism. The book more fully articulated the political lessons Schlesinger had stated in The Age of Jackson (1945): Jacksonians were pragmatic realists who advanced social reform by discarding overly optimistic views of human nature and other outmoded ideas against using government power. Pragmatic liberals avoided becoming ideological by testing their ideas against experience, keeping them abreast of change, and preserving freedom. The Soviet Union’s postwar external expansion and internal subversion, Schlesinger said, threatened American freedom. The Soviets must be met globally with tough-minded containment and defeated domestically with left wing non-communist reforms. Measures safeguarding the accused, he said, set his domestic anti-communism apart from McCarthyism. United States intervention in Korea prevented Soviet expansion elsewhere in the world. These self-righteousness domestic and foreign campaigns were regrettable yet necessary, Schlesinger declared. Yet he minimized how witch-hunters ruined hundreds of careers.

During the Fifties, Schlesinger argued, changing social conditions demanded a shift from the “quantitative liberalism” of the Great Depression to the “qualitative liberalism” needed for a mass society. His calls for expanded medical care, education, housing, minority rights, and urban planning bore fruit in Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society until curtailed by Vietnam and the GOP. When the United States escalated the Vietnam War, Schlesinger distinguished between John Foster Dulles’s obsessive, conservative anticommunism and JFK’s rational, liberal variety. Even though the CIA as well as the State and Defense Departments had institutionalized the former, Schlesinger insisted JFK would have withdrawn from Vietnam if he had lived. When both LBJ and Richard Nixon found victory elusive, Schlesinger’s retained his realistic idealism and globalist assumptions. The United States must resist communist expansion wherever its vital interests were threatened and advance human welfare worldwide. Despite Schlesinger’s non-ideological claims, his defense of liberalism seemed ideological to me. It became an interest-bound defense of the status quo. His apologetics for Jackson, FDR, and JFK revealed pragmatic intellectuals relying on powerful presidents for furthering liberal reform, which condemned them to infidelity or impotence. If thinkers remained loyal to leaders acting at times in an authoritarian manner, they betrayed their liberal values. If they did not, they could not implement their agenda.

In his reply to my arguments, Schlesinger stated: “Mr. Engelhardt is essentially fair-minded and often generous, though not always, in my view, quite accurate.” He was not an ideologue because my use of Karl Mannheim’s bizarre definition of ideology excluded Marxism. His anti-Stalinist stance should not be questioned because the Soviets seriously threatened the United States. He had not sacrificed domestic reform to advance foreign policy. Indeed, fellow liberals accused him of doing the opposite. I had made “slippery slope arguments,” and should not criticize him without stating my alternatives to policies he advocated.

After Schlesinger’s sweeping dismissal, would anyone find merit in my essay? My promised opportunity to respond had not been honored. Perhaps it was a matter of space or deadline. Besides, what could a rowboat say after being overrun by an aircraft carrier. Still, some scholars cited my article: Kurt M. Beck, “What was Liberalism in the 1950s?” in Political Science Quarterly 102(Summer 1987); William Leuchtenburg in Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. and the Challenge of the American Past (1997), edited by John P. Diggins; Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing (1999), Vol. 1, edited by Kelly Boyd; and Ruth Feldstein, Black and White: Race and Sex in American Liberalism (2000).

Factors other than Schlesinger’s critique kept me from writing a book about 20th century liberalism. Carving two articles from Chapters Three and Six of my dissertation expanded to six over the next few years. Then the Concordia College centennial history project happened. After I finished that book in 1991, I decided to continue researching local history in nearby archives and avoid the hassle of funding trips to far-off places. Besides, Ronald Steel, Walter Lippmann and the American Century (1980), Richard Wrightman Fox, Reinhold Niebuhr: A Biography (1983), and Kevin Mattson, When America Was Great: The Fighting Faith of Post-War Liberalism (2004) preempted most intellectual contributions I might have made.

The Persons festschrift appeared in 1982, when he retired after directing thirty-seven doctoral dissertations at Iowa. It included Cravens’ preface; “Stow Persons as a Historian of American Intellectual Life,” written by Merle Curti, a major scholar who similarly had defined the field; eight essays crafted by doctoral students; and two appendices: “Publications of Stow Persons,” prepared by Harold B. Wohl, and “Doctoral Graduates of Stow Persons and Dissertation Titles.” I considered my presence ironic in light of my graduate school struggles. Still, it is nice to be numbered among such well-known graduate student contemporaries as Thomas Schlereth at Notre Dame and Mary Kelley at Dartmouth and, later, Michigan. The anthology received just three albeit favorable reviews, which likely humbled us all. Being ignored by a University of Washington reviewer troubled me less after David Noble (University of Minnesota) praised my “valuable analysis of the transition from an overtly Protestant base for citizenship to that of a civil religion.”

“Religion, Morality, and Citizenship” argued nineteenth century American public education secularized slowly because schoolmen persisted in basing citizenship on moral training grounded in Christian values. Schools manifested two types of religion in Iowa: First, Horace Mann’s non-sectarian Christianity featuring Bible reading without comment and common moral virtues established in 1858 and upheld by the state Supreme Court in 1884. Second, a Christian-derived civil religion emphasizing America as a special nation under God’s guidance and judgment. The Protestant middle ground of non-sectarian Christianity evolved over many years into another version of the lowest common denominator. Civil religion avoided Catholic and Lutheran charges of sectarian religious instruction while still grounding morality in transcendent, now unspecified Christian values.

Rote memorization and school readers inculcated religious, moral, and civic beliefs. As literature, nature study, and patriotic stories displaced explicitly Christian materials, children still acknowledged God and learned the same moral lessons as before. Like American Protestantism, schoolbooks discarded theological doctrines and concepts for a religion of ethics. American flag and national holiday observances, products of a national movement dating from the 1880s, paralleled this shift. By 1913, Iowa law required every school to raise the flag daily and manuals issued by the Department of Public Instruction enshrined civil religion with programs of songs and recitations for Thanksgiving, Washington’s Birthday, and Memorial Day. After the Iowa State Teachers Association (ISTA) Committee on Bible Study in the Schools peaked in 1927 with 132 high schools giving credit to 4,394 students, 30 percent of those enrolled, Christian beliefs remained implicit in many other activities. Teachers were an effective Christianizing influence because most were church members. The prize-winning Iowa Plan (1922) enshrined the Character Education Movement in Iowa schools so most rural children formulated and memorized moral creeds, codes, and slogans; discussed moral case materials in opening exercises and history, civics, and literature classes; and read biographies and stories aloud, observed special days, and held flag drills.

Soon after Ideas in America’s Cultures appeared, Mid-America: An Historical Review at Loyola University of Chicago published “Citizenship Training and Community Civics in Iowa Schools,” which advanced three claims. First, administrative and pedagogical progressives developed more sophisticated civic education techniques to Americanize higher enrollments of poor, immigrant working class children. Second, rural midwestern educators became evangelical modernizers in adapting urban methods and practices for better inculcating traditional moral values. Third, Iowa schoolmen and political leaders—caught up in the patriotic zeal of United States entry into World War I—joined the national trend toward legislating more formal public school citizenship training.

Starting in the centennial anniversary year of American independence, ISTA conventions annually heard addresses and adopted resolutions calling for better civics teaching. During the 1890s, Superintendent of Public Instruction Henry Sabin championed modernization of the public schools. Later political progressives like Governor Albert B. Cummins embraced Sabin’s reforms when Iowa’s foreign-born population rose to 16.9 percent and the state experienced 381 strikes involving 32,930 workers in 831 factories and mines. The General Assembly enacted compulsory education, state teacher certification, and a new State Department of Public Instruction with expanded powers. At the same time, pedagogical progressives applied John Dewey’s ideas and created community civics. Dewey maintained that civic education in an industrial society would not be effective until teachers tapped the child’s actual experiences. In particular, Dewey argued that the school itself should be made an active community connected with life in the larger industrial society. Arthur W. Dunn’s textbook, The Community and Citizen (1907), made it a national movement. David Cloyd’s Civics and Citizenship (1916), a program for the Des Moines schools, became the earliest Iowa example.

In 1919, war-generated xenophobic Americanization compelled the General Assembly to mandate English as the language of instruction for secular subjects and the teaching of American citizenship in all public and private schools as well as the United States and Iowa constitutions not later than the eighth grade. The Department of Public Instruction’s Course in American Citizenship in the Grades for the Public Schools of Iowa reveals the peculiar blend of modern and traditional, progressive and conservative elements, which typified community civics. The document’s methodological sophistication was modern. It socialized civics instruction by applying the school community experience and “learning by doing.” Teaching the citizenship precepts practiced in community life showed pupils how government operated at all levels and how virtuous, law-abiding productive individuals and properly arranged homes, farms, and businesses made their contribution to community wellbeing. Conservative elements included traditional American assumptions about character as the basis of citizenship and patriotism as an essential part of every citizen’s training and preparation for life. The community civics emphasis on group-life, teamwork, and cooperation better equipped students for serving the decade’s newly emerging, more tightly organized managerial capitalism. Its stress on interdependence of local, state, and national communities, taught future farmers and farm wives how Iowa fit into a more integrated urban-industrial society. Administrative progressives mirrored this lesson by creating a more tightly organized and supervised state system of public education.

Summertime visits to our parents enabled my writing four additional dissertation-related articles for the Annals of Iowa. When we were at Jo’s family in Adel, I would spend two or three days in Des Moines at the Iowa State Historical Society. On the way to my parents in Elkader, I stopped in Iowa City at the State Historical Society, School of Education Library in Seaburg Hall, or the University Library Special Collections. It would have been less time consuming and more professionally rewarding to have written a book instead. Yet I did not think my dissertation worthy and only learned how to craft a book by composing the articles. My apprenticeship served me well later when commissioned to write the Concordia College centennial history.

“Schools and Character” detailed how educational reformers aimed to instill industrial virtues in Iowa schools between 1890 and 1930. Hard work was the core of moral life in American Protestant culture; it created useful citizens, enabling them to avoid the temptations of idleness and to gain increased wealth and higher social status. Regular school attendance and study taught children the disciplined use of time and made them more reliable workers. Chauncy P. Colgrove, an Iowa State Normal School professor of education and later Upper Iowa College president, took a leading part in emulating urban administrative and pedagogical progressives and calling for modernized educational structures and methods to make Iowa public schools more efficient instruments for training industrial virtue. He authored The Making of a Teacher (1908), The Teacher and the School (1910), and the Course of Study (1906 and 1913), which the Department of Public Instruction distributed to every Iowa school. These works revealed new educational currents emphasizing psychology, child study, and habit formation. As good habits safeguarded society, teachers ought to create model environments for inculcating moral virtue. Properly managed institutions developed habits of “regularity, methodical work, obedience to rightful authority, and a sense of personal responsibility.” Schools instilled internalized discipline, which later enabled citizens to perform jobs and civic duties daily thereby assuring social stability.

Iowa movements to establish manual training and improve country life made similar claims. Because most children would earn livelihoods by physical labor, agriculture, manual training, and domestic science better equipped them to find employment and become good citizens. The enhanced utility and practicality, which Colgrove and other reformers demanded, similarly found expression in the intertwined movements for community civics and character education. Iowa institutionalized the former in a 1919 law requiring the teaching of citizenship in all grades of the state’s public and private schools. The Department of Public Instruction Course in American Citizenship declared citizens must become self-supporting society member. To this end, pupils should learn “habits of punctuality, thrift, and industry;” transfer these school-learned habits to the home, farm, or store; uphold the right of private property; and embrace the duty to be self-supporting. The Iowa Plan similarly featured traditional economic and political beliefs wedded to sophisticated pedagogical progressive methodologies—the school as democratic community, life adjustment developed from specific character education tasks, and scientific measurement. By 1930, educators could assert confidently that pupils attending better-organized Iowa schools were being trained in the habits of industrial virtue healthy Republics required.

Iowa State Historical Society financial woes delayed publication of “Henry Sabin” and “Compulsory Education” until 1987. The former at last provided a biography of Iowa’s foremost pioneer schoolman. The Connecticut-born Amherst College graduate relocated to Iowa as the Clinton school superintendent in 1871. He was elected ISTA president in 1878, four-time State Superintendent of Public Instruction between 1888 and 1898, and chair of the National Education Association Committee of Twelve on Rural Schools (1896-1897). Historians David Tyack and Elizabeth Hansot have characterized Sabin’s style of educational leadership as “the aristocracy of character” He traveled the state like a frontier evangelist preaching the Protestant, republican, and capitalist common school ideology and raising consciousness for building public schools to make citizens virtuous and the nation Christian, republican, and prosperous. Sabin conducted summer normal institutes for country schoolteachers in Clinton and neighboring counties. He began and ended meetings with hymns and prayer, gave sermons on his vision of educational salvation, and taught didactics, grammar, and history.

When Sabin held the post of State Superintendent just over 12,000 of Iowa’s nearly 13,000 schools were rural and ungraded. Farmers rejected state supervision and insisted on local control. Despite limited powers and a small staff, Sabin urged more centralized administration, professional supervision, and consolidation of small district setting an agenda for reforms implemented during the early 20th century. When the 1890 census revealed 42.3 percent of school children were foreign born or the offspring of foreign-born parents, Sabin ruled that the common branches must be taught in English. He also furthered American citizenship with personal appeals to local districts for compliance with flag ceremonies and Washington’s Birthday and Memorial Day programs. County superintendents distributed his Handbook for Iowa Teachers to every common school in ninety-five of ninety-nine counties. After stepping aside as State Superintendent, Sabin lectured at normal institutes, headed the department of education at Highland Park College in Des Moines, edited Midland Schools (1899-1901), and authored Common Sense Didactics (1903). It is surprising Sabin criticized the new generation of “administrative progressives” for neglecting morality and being preoccupied with salary and position. He might have been more sympathetic had he lived to see how these new “managers of virtue” implemented Character Education and Community Civics programs during the 1920s.

My “Compulsory Education” article depicted how Iowa became the 33rd and last state outside the South to enact required attendance a half-century after Massachusetts first did in 1852. For more than two decades, farmers—who controlled one-room country schools—blocked compulsory education laws sponsored by schoolmen. During the Nineties, Wisconsin Bennett and Illinois Edwards law controversies kept Iowa Republicans from backing measures opposed by ethnic and religious voters. Meanwhile, agricultural occupations declined and manufacturing jobs nearly doubled. Urban growth increased lobbying clout of the American Federation of Labor and Federation of Women’s Clubs. It helped elect progressive Republican Albert Baird Cummins as governor. With approval from four Iowa Lutheran synods and Archbishop John J. Keane, the Dunham compulsory attendance bill passed the House and Senate with large majorities in 1902. State supervision was limited. Teaching in English was not required. Children might attend public, private, or parochial schools that taught the common branches. Principals made attendance reports for just twelve weeks annually. Local boards named truant officers. Noncompliance led to amendments and new legislation. A child labor law in 1906 banned employment of children under fourteen and established a ten-hour day for those under sixteen working in businesses and industries having more than eight employees. In 1913, Iowa set the age limit for leaving school at sixteen, or completion of the eighth grade.

As part of the progressive trend toward more state control, compulsory education altered Iowa schools in the areas of record keeping, attendance, vocational education, and citizenship. It added hundreds of new students, bringing practical subjects into the curriculum. In 1913, the General Assembly enacted thirteen of eighteen measures the Better Iowa Schools Commission proposed, including formation of a Department of Public Instruction with three rural, grade, and secondary school inspectors; state aid for consolidated schools; and twelve weeks of normal training for every teacher. All consolidated schools must teach manual training, agriculture, and domestic science and the Iowa course of study recommended these subjects for all rural schools. By the twenties, teaching the common branches in English and specific American citizenship training were also required. German Lutherans and Irish Catholics complained, but usually complied with these new state-imposed educational standards.

My dissertation research started with a paper for Professor Sidney Mead on the founding of Iowa common schools. After foolishly excluding it from the completed work, I submitted the essay for publication a quarter century later. Although editor Marv Bergman accepted the article provisionally with updated historiography, I decided to research Iowa politics more thoroughly, making it my best article when it appeared in 1997. “The Ideology and Politics of Iowa Common School Reform,” set Iowa’s educational awakening in the context of an expanding market economy in which. railroads created an integrated national market, stimulated immigration, and provoked partisan debate about infrastructure growth. Iowa yielded large surpluses of corn, wheat, and pork, and its population more than tripled to almost 700,000. Democratic state dominance ended in 1854 when antislavery Whig James Grimes won the governorship and soon helped found the Republican Party, a coalition of antislavery Whigs and Democrats, which gained electoral strength by retaining Whig support for government backed banks, public schools, temperance, and Sabbath observance. Democrats attacked Republicans as abolitionists, disunionists, and miscegenationists, and limited state control of banks and schools.

In 1856, Governor Grimes appointed a three-man school commission headed by well-known educator Horace Mann. When the Sixth General Assembly failed to enact the Mann Commission Report school reformers shifted their hopes to the constitutional convention. It set up public education in a document narrowly adopted on September 3, 1857 despite bitter Democratic attacks. Urged by Grimes, the ISTA, the superintendent of public instruction, and Republican and Democratic newspaper editors, the General Assembly enacted a common school system. During the next few years, Democrats—backed by farmers favoring local control—dismantled most provisions for centralized control. Sub-districts gained powers to tax and elect township district board members; the township district system soon collapsed with the rapid growth of independent rural districts. County superintendents survived without visitation authority and the restored state superintendent of public instruction replaced the abolished state board of education. Yet all localities still established free tax-supported schools for all children and teachers’ institutes were regularly scheduled to improve instructional quality. Enrollment and regular attendance respectively rose to 71 and 40 percent by 1863, and continued growing thereafter. Iowans valued common schools for educating rural children in republican, capitalist, and Protestant values and equipping them to become morally responsible and productive citizens of an agricultural state integrated into a national market and a growing urban-industrial society.

My intensive historical study of Iowa education garnered as much respect as comedian Rodney Dangerfield. Just five editions of my dissertation “The Common School and the Ideal Citizen” were published between 1969 and 1974. Only nine World Catalog Member Libraries currently hold copies. Rural historian David Danbom, an NDSU professor and subsequently a close friend, is one of few who used my dissertation in writing his, which Iowa State University Press published as The Resisted Revolution: Urban America and the Industrialization of Agriculture, 1900-1930. My publications did no better. Annals of Iowa editor Marvin Bergman cited five of them in the Iowa History Reader, an anthology he compiled and reissued in 2009. While Bergman omitted education from the collection, he credited Kevin Johnson and me for seriously reinterpreting the subject. He failed, however, to clarify how my work was more thoroughly grounded in American educational historiography than Johnson’s narrower administrative focus. On the other hand, Bergman honored me with an invitation to submit entries about “William Robert Boyd,” “Henry Sabin,” and “Homer Horatio Seerley” for The Biographical Dictionary of Iowa, which he edited. I was pleased to have him acknowledge my scholarly work in this way.

So far as I know, no one ever cited “Religion, Morality, and Citizenship,” which is unfortunate because the persistence of religion in supposedly secular public schools was my most significant dissertation finding. Being part of a widely overlooked festschrift may account for it being ignored. Tracy L. Steffes mentioned “Community Civics” in her School, State, and Society: A New Education to Govern Modern America, 1890-1940. Pamela Riney-Kehrberg cited “Compulsory Education” and “Schools and Character” in her Annals of Iowa article on rural childhood. Julie A. Reuben included “Ideology and Politics” on her supplemental reading list for a Harvard University history of education course and David Mathews cited it in his Why Public Schools? Whose Public Schools? My “Henry Sabin” entry for The Biographical Dictionary of Iowa unsurprisingly lists “The Aristocracy of Character” as a source.

The Centennial History and After

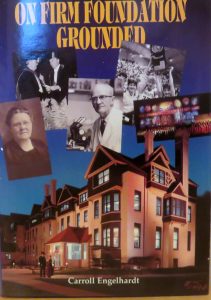

My first book appeared shortly before my 50th birthday. On Firm Foundation Grounded: The First Century of Concordia College emerged from an unlikely chain of events. Summoned by President Dovre to talk about writing the college centennial history, he did not anoint me for the task as I had expected. After sociologist Ray Farden turned him down, Dovre named Tom Christenson, a philosopher. Both were Lutherans and Concordia alumni, with long institutional ties, important qualifications that I lacked. After a summer’s research, Tom requested a co-author. He and the president agreed on me. The project became mine alone when Christenson abruptly left the college. Following the president publicly announcing my appointment, a procession of the concerned trooped into his office. I imagine many thought a non-Lutheran outsider and state school graduate could not be trusted. Some, I expect, did not want a dull, unreadable academic history. They preferred a photograph-filled coffee table book compiled by them and brimming with alumni reminiscences and colorful stories. In any case, I was mindful of many people looking over my shoulder while toiling six summers and a year’s paid leave to publish a volume for the 1991-1992 centennial celebration. My logged hours totaled about two and one half years of forty-hour weeks. It did not matter that my summertime hourly wages were well below the minimum. An opportunity to publish a book—not money—motivated me.

Concordia’s character had puzzled me from my first fall workshop starting with prayers, hymns, and homily and ending with an evening banquet audience singing “The Hymn to Concordia.” Why did presidents frequently stress Lutheran identity? Why did others so often emphasize Concordia family? To answer these questions, I wrote the centennial history as an institutional biography detailing the life of a faith-based educational community and selected the first line of the Concordia Hymn—“On Firm Foundation Grounded”—as the title. Composed for the 40th anniversary observance and ritually sung thereafter at many college events, the hymn defines Concordia as a community of God’s people called to the vocation of education. My four-part organizational scheme soon emerged from some institutional peculiarities. Although founded in 1891 as a college in name, Concordia remained an academy in fact until the first collegians graduated in 1917 and comprised the entire student body almost a decade later. Hence, “From Academy to College, 1891-1925” became Part I and presidential administrations of long-serving J. N. Brown (1925-1951), Joseph L. Knutson (1951-1975), and Paul J. Dovre (1975- ) constituted Parts II, III, and IV.

To ensure finishing on schedule, I researched and wrote a draft of each part during the summers of 1985, 1986, 1987, and 1988 respectively. An editorial committee composed of Dovre, former administrators Carl Bailey and J. L. Rendahl, Head Librarian Verlyn Anderson, and church historian James Haney read and commented on each section as I finished them. An initial draft therefore had been read and critiqued before I wrote the final version during a one-year paid leave. Richard Solberg, who authored Lutheran Higher Education in North America, reviewed the manuscript at Dovre’s request before publication. I was pleased when good friend Jim Haney confided that Solberg had judged the book “really good!” Sadly, not all agreed.

Gaps in institutional records complicated my task. Always short of funds and buildings, Concordia did not create an archive until 1980 when it hired retired librarian Margaret Nordlie to organize surviving documents. Fortunately, she and her colleague Anna Jordahl began gathering materials decades earlier. Archivists and librarians Joan Olson, Saint Olaf College, Charlotte Jacobson, Norwegian American Historical Association, Paul Daniels, Luther Northwestern Seminary, and Margaret Anderson, Augsburg College, generously gave me access to their collections. Archivist Sharon Hoverson succeeded Nordlie and expanded holdings despite library remodeling, which put materials in boxes during summers when I needed them most. Student assistant William Block extended my research with his work at the Clay County Historical Society Archives. He also persuaded me to learn word processing and buy a personal computer. Bill subsequently earned a University of Minnesota doctorate, became a quantitative historian, and for many years directed the Cornell University Institute for Social and Economic Research (CISER). He still works as a researcher at Cornell.

Concordia’s first collegians graduated the same year that the Norwegian, Hauge, and United Synods merged to form the Norwegian Lutheran Church in America. The new church soon moved the Park Region College program from Fergus Falls to Moorhead, giving Concordia a brighter future. Capable President J. A. Aasgaard built a gymnasium, bookstore-post office, and library; bought North Hall, a president’s house, and sixty-five acres for future growth; and secured the appointment of his successor, J. N. Brown. While Brown’s United Synod background recommended him to Aasgaard, it alienated former Norwegian Synod pastors, congregations, and Park Region faculty, who wanted one of their own. Although festering synodical differences plagued his presidency, Brown initially enjoyed great success. He advertised Concordia as a modern church college, stressing the value of Christian education, opposing the anti-Christian influences of modernism and evolution, establishing criteria for hiring better qualified and paid Lutheran faculty, and raising the necessary $500,000 endowment required for securing North Central accreditation. The later ensured secondary schools would hire Concordia graduates as teachers and universities would admit them to graduate study.

Unfortunately, the Great Depression shattered Brown’s “builder president” dreams. Yet his early success gave the school strength to survive the economic hard times and World War II. Talented and dedicated professors taught the Liberal Arts and Sciences; Deans of men and women implemented modern student personnel practices; and students diverted themselves with a plethora of Lutheran organizations as well as societies, athletic teams, and other secular extracurricular activities. The war imposed less strain than feared. Average enrollment stabilized sufficiently to balance budgets. The Golden Jubilee and Memorial Fund Campaigns raised monies for badly needed but long-delayed buildings, which became even more pressing when postwar enrollment more than tripled prewar numbers to 1,316 in September 1948. Concordia accommodated this surge by erecting a new men’s dormitory and acquiring several war surplus buildings. Boe’s Bunkhouse housed seventy-two veterans before it became a classroom and office unit. A new science building emerged from four hospital units moved from a Sioux Falls air base. A new athletic field appeared on the sixty-five-acres President Aasgaard had purchased two decades earlier. An ill-fated windstorm delayed completion of the Memorial Auditorium – Field House for nearly two years and frustrated Brown’s hopes the facility would crown his retirement and the college’s 60th anniversary. Concordia’s inadequate physical plant, limited financial resources, and rumored factionalism complicated the search for Brown’s successor.

Fortunately, the Reverend Joseph L. Knutson took the post in 1951 after two more favored candidates had refused. Knutson accepted because the school had institutional vitality, several talented professors, and a natural Lutheran constituency in the Red River Valley. He successfully promoted the institution by speaking widely throughout the corporate territory at churches, service clubs, and commencements and building a talented and trusted administrative team. Business Manager William Smaby—college roommate, longtime friend, and banker—cultivated local businessmen and tapped Minneapolis banks for construction loans. Admissions Director J. L. Rendahl harvested collegians from lists based on test scores and Lutheran church membership. Steadily rising enrollment enabled federal loans to build badly needed dormitories. Dean Carl Bailey had the intellectual stature as an atomic physicist to command faculty respect and elevate academic quality. Development Vice President Roger Swenson raised gift income to a level that sustained physical expansion. Student Personnel Deans Victor Boe and Dorothy Olson sagely supervised an expanding student body. When Knutson retired in 1975, he had an impressive record. Sixteen structures, comprising more than one-half of the physical plant had been erected at the cost of more than $16 million. Another $2 million had been expended for remodeling four older structures. Endowment and deferred gifts increased while enrollment grew from 890 to 2,482. Although Knutson stoutly maintained Lutheran identity, the Fargo Forum credited him with broadening the college constituency to include Catholics and other Protestants, which had facilitated his fundraising success.

Vice President for Academic Affairs Paul J. Dovre assumed the presidency. Knutson had highly praised his management, planning, speaking skills. Dovre immediately proposed a capital fund campaign. Skeptical Regents wondered: “Why does this kid want all that money?” Dovre based his case on the need to build two multimillion-dollar buildings without federal funds and to accelerate institutional progress with larger annual gifts. Founders Fund I exceeded its goal and raised nearly $12 million. Founders Fund II sought $21.5 million and harvested $26.5 million. The Centennial Fund sought $45.6 million and reached $58 million. Endowment grew tenfold from just $2 million and the schoolhouse greatly improved with Bogstad Manor, Jones Science Hall, Olin Art and Communications Center, Bogstad East, Mugass Plant Operations Center, Berg Steam Plant, and Outreach Center. Academy, Grose, Bishop Whipple, Brown, and Fjelstad halls had been made handicap accessible and more energy efficient. For the first time, Concordia had funds for enhancing campus beauty. Architect E. A. Sövik designed plazas graced by sculptures to make spaces between buildings aesthetically pleasing. Mosaics, murals, and paintings enlivened interiors. Erecting a bell tower capped by a six-foot cross as the focus of the centennial mall at last gave Concordia an attractive main entrance.

Funding largesse strengthened personnel and program quality. The North Central Review (1983) documented fulfillment of academic purpose. Assessment data confirmed improved communication skills and increased appreciation for religious and cultural diversity as well as how moral beliefs shaped issues and individual actions. Alumni surveys revealed an awareness of personal value development during college. Enrollment first topped 2900 in the centennial year. Administrators fretted about the declining percentage of Lutherans and the failure to boost minorities above 2 percent of those enrolled. Freshmen and sophomores lived in dormitories and had limited intervisitation. Healthy behaviors were promoted and bad ones curbed. Alcohol, drugs, and gambling were forbidden. Smoking was discouraged. Birth control devices were not distributed. Two campus pastors and the Campus Ministries Commission coordinated myriad activities like daily chapel, Wednesday night communion, Bible studies, tabernacles, retreats, residence hall devotions, clown ministry, and community service. Many took part in extracurriculars like athletics, debate, forensics, music, theatre, and student government. The annual Christmas concert featured three hundred musicians and attracted almost 30,000 people. It symbolized Concordia Christian community, drawing together collegians and constituents in celebration of a central faith event. Based on Soli Deo Gloria—“To God Alone the Glory”—the college carried on its vocation through graduates serving the world.

The publication of On Firm Foundation Grounded in late August 1991 ended my long days of toil and was greeted with deafening silence from most of the community. A few had kind things to say. Saint Olaf President Emeritus Sydney Rand sent a congratulatory note. Choir Director René Clausen, an important personage at Concordia, called it “a good piece of work.” A regent, speaking to the convocation gathered for the “Together in Mission Celebration,” described it as “a book with a lot of heart.” President Dovre in a Concordian interview credited me for “a good job of balancing detail with institutional themes and trends.” He also graciously gave me full credit in the many historical talks that he delivered to community groups during the centennial observance year.

Dr. Phyllis Burgess Andersland ’55 and MSUM English Professor Dr. Clarence Glasrud expressed the harshest criticisms. She sent reams of documents detailing “mistakes” to Dovre, the college archivist, and me. She also volunteered to supervise an immediate rewrite of a second edition. As the daughter of long-time Professor of Psychology Thomas Burgess, she believed I had slighted her father’s contributions to Concordia. Editorial committee member Carl Bailey dismissed her complaint as “a problem of inches.” He also noted that I had not mentioned how often Burgess had been mocked for his hypnosis experiments. Glasrud wrote a nit-picking review for a local historical journal listing my errors (including some I had not made). At the time, he had published two volumes of the MSUM centennial history, which he never finished. In an address to a Moorhead Rotary luncheon, which he attended, I had remarked on “not writing a book of lists” and “finishing on time.” Did he regard these comments as veiled criticisms of his own work, and repay me in kind?

While I naively anticipated being overwhelmed with invitations to speak during the yearlong centennial celebration, a Kiwanian soon set me straight: “Why settle for an author when we can have the president instead?” Similar preferences prevailed at book-signings I shared with Dovre and Knutson. When people sought Knutson’s signature, he graciously deferred to me and said: “All honor to the author.” Although faces betrayed reluctance, everyone respected his request. As I witnessed how good Knutson was with people on these occasions, my appreciation of him grew. When Director of Theatre Jim Cermak introduced his mother, Knutson greeted her in Czech and immediately won her adoration. “There were a lot of Bohemians in Jackson, Minnesota, when I was growing up,” he explained afterward. Knutson apparently heard that the Andersland and Glasrud criticisms had discouraged me. He later took the time to lift my spirits at the fall faculty dinner: “On the whole you did a very good job on that book. And you were very fair in what you said about me.” He died the next day, making me the last person to whom he extended pastoral care as he had done with so many at the college over the decades.

I wrote On Firm Foundation Grounded with two audiences in mind: professional historians and college alumni and friends. The book probably disappointed both. It did well initially, selling 1800 copies during the first year. The centennial commission had printed 5000 copies for the same cost as 2500. It assumed the Alumni Affairs Office would continue a telemarketing campaign after the celebration ended. Constituent complaints soon ended this effort. No one knows how many books were sold or given away thereafter because no records were kept. When the 125th anniversary rolled around, Director of Library Laura Probst objected to storing the nearly 2500 unsold copies. She arranged with college officials and offices to save five hundred volumes for institutional use and discarded the rest. I took a box of twenty-four. Like everyone else, I have found them hard to give away. Perhaps I should have consulted colleague Hiram Drache about how he had sold 12,000 copies of his first book, The Day of the Bonanza. It likely would not have mattered because I lacked Hiram’s talent for self-promotion.

Having failed to write an alumni best seller, I fared no better with scholars. Institutional academic histories are “a black hole” for those seeking to enhance their professional reputation. Most journals did not review the copies Concordia sent to them. The Journal of American History listed it among publications received, as I expected. It reviewed volumes about major research universities or prestigious eastern liberal arts colleges, but never midwestern Norwegian Lutheran institutions. Minnesota History printed a brief, positive notice. An inconclusive and a favorable review respectively appeared in Annals of Iowa and South Dakota History. Even my attempt to secure approval from an absent father failed when my graduate school mentors Stow Persons and Sidney Mead did not bestow the praise I desired. Stow called it “dense;” I would have preferred “thickly described.” He did say somewhat ruefully: “I hope your community gives you more support than mine did me.” Apparently, folks at the University of Iowa had not shown any interest in his excellent history of that institution. Sidney urged me to speak about my book with another of his students. Nothing came from his suggestion.

On Firm Foundation Grounded has been similarly ignored in the years since its publication. It is catalogued worldwide in twenty-seven libraries. Citations have appeared in Religious Higher Education in the United States: A Source Book, ed. Thomas C. Hunt and James C Carper; Eric Childers, College Identity Sagas: Investigating Organizational Identity; and Preservation; and Educating Through Popular Culture: You’re Not Cool Just Because You Teach, ed. Edward A Janak and Ludwig A Sourdot. The most rewarding application of my research is by Kurt W. Peterson,” A Question of Conscience: Minnesota’s Norwegian American Lutherans and the Teaching of Evolution,” in Norwegians and Swedes in the United States, ed. Philip J. Anderson and Dag Blanck. More recently, David Cooley referenced it for his 2016 UND Master’s thesis: “Black Power in a ‘Lily-White’ School: The Black Campus Movement At Concordia College Moorhead, Minnesota.”

Presenting professional conference papers and submitting them to academic journals would have better served my scholarly goals. David Danbom invited me to take part in a Northern Great Plains History Conference session on “Confessions of Kept Historians: The Pitfalls and Promise of Institutional History.” The centennial deadline kept me from giving any more papers until the book had been published. I then reversed conventional wisdom, presenting “Concordia Goes to War” at the Northern Great Plains. When I later sent it to Minnesota History. Editor Anne Kaplan rejected it as plagiarism. “How can I plagiarize myself?” I fumed. Yet the topic had appeared in print and she would not repeat the mistake. I gave “Concordia and the Jazz Age” as a Tri-College History Lecture, offered a revised version at the Northern Great Plains, and reworked it for the History of Education Quarterly only to be turned down. I modified both essays from time to time over the next twenty years while working on another book project.

Happily, former colleague James Hofrenning asked permission to use a book chapter to introduce an anthology he edited and published: Cobbers in WW II: Memoirs from the Greatest Generation. Instead, I sent him a newly revised version of “Concordia Goes to War,” which suited his purposes perfectly. Thus encouraged, I again tried “Jazz Age” at the History of Education Quarterly even though editors there had turned it down two decades earlier. Their new rejection came with five single-spaced pages of fruitful critique from three readers. One advised, “Send it to Minnesota History.” Editor Anne Kaplan was more amenable, this time. Thanks to suggestions from her and anonymous readers, the paper finally cohered as a midwestern case study in a way that I had not achieved previously. “Modernity Confronts Tradition” came out as a lead article and caused some “buzz” at Concordia. Former Burlington Northern CEO and regent Norman Lorentzsen called the Advancement Office. Other alumni spoke about it to President William Craft. Dean Eric Eliason received several copies in the mail with appended comments about its superior quality. Just as with “The Ideology and Politics of Iowa Common School Reform” persistence over a quarter century finally paid off with publication of a much-improved essay.

As planning began for the college’s 125th anniversary fête, rumors circulated that I would be asked to write something. Not wanting an assignment without sufficient time for completion, I offered to prepare without pay a second volume of no more than two hundred pages. President William Craft called the offer “generous.” Yet he waited three months before summoning me to his office where we finalized the deal with a handshake. In the meantime, Chief Financial Officer Linda Brown had determined the cost for a Minneapolis firm to print three hundred copies with the same cover design as the centennial history. Craft generously gave me access to the Board of Regents papers. I again decided to take the title from Hymn to Concordia. Produced by the Communications and Marketing Office, edited by Erin Hemme Foslie, and attractively designed by Lori Steedsman, the completed volume met the celebration deadline.

Concordia Fair Doth Stand: The College Begins Its Second Century, 1991-2016 proved harder to compose than the first volume. It is difficult to write a history of current events especially when an institution and its educational context has grown more fluid and complicated. There were a lot more living witnesses, and much more stuff to winnow. On the other hand, information technology made some tasks easier. Email facilitated communication with the subjects of my study. I pestered pastors, professors, vice presidents, regents, and even presidents with questions about policies, plans, and events. Most replied within minutes, hours, or days. Others sometimes belatedly responded apologetically for misplacing my request. Such generosity showed collegiate community spirit. The Concordian digitized similarly simplified researching newspaper files. The time saved quickly removed any guilt about having my work made too easy.

Organization turned out to be particularly challenging. Opening and closing chapters on the centennial and the 125th anniversary seemed obvious. Strong objections from the president’s assistant to the former did not change my mind. I devoted four chapters to presidents because as Ralph Waldo Emerson once wrote: “An institution is but the lengthened shadow of a man.” This is especially true of small colleges where executives significantly shape the schools they lead. “Can Concordia Remain Lutheran?” appealed to me because presidents Knutson and Dovre had so often posed the question. Early research in board minutes and reports gave the book a corporate business focus that some found objectionable. To compensate, I composed four additional chapters: “Technology Trials and Triumphs,” “Teaching and Learning,” “Toward an Integrative Global Curriculum,” and “College Life as Co-Curriculum.”

Concordia Fair Doth Stand received an even more under whelming response than On Firm Foundation. It can be found in only two World Catalog member libraries. The smaller 125th anniversary celebration featured only one book signing at a reception after the chapel commemorating the college’s birthday. The president said, “I’m glad to have it.” Presidential Associate Tracy Moorhead thanked me for “your special gift to the college.” Larry Papenfuss, Director of the Dovre Center for Faith and Learning, told me: “Your Lutheran identity chapter is being read and discussed.” No one else commented or complained. I did not mind the peace and quiet. Nor do I regret a decade spent writing institutional histories of the place where I worked. Most gratifying has been the use new presidents have made of On Firm Foundation. Tom Thomson quoted it in his inaugural address. Pamela Jolicoeur called it “the Bible,” which made my head swell until learning it is a term used by student workers in the Archives. Craft creatively used it as “a guide and inspiration” in his many speeches about Concordia. Current president Colin Irvine similarly employed it fruitfully for story telling in his inaugural speech.

Researching and Publishing Books

By the time I published the centennial history, a new dean had changed Concordia’s approach to scholarship. Vice President of Academic Affairs David Gring fostered writing grants to fund joint faculty-collegian research. Bush Scholars Program recipients praised the educational benefits of students examining questions of value, society, or disciplinary importance and pondered how to replicate this experience for larger numbers in the classroom. The newly initiated Student Lecture Series recognized outstanding collegiate researchers and offered them the opportunity to present their work publicly. The 1991-1992 centennial scholars program similarly funded faculty and student disciplinary and pedagogical co-inquiry. The college hoped the experience would teach students more about knowledge formation and give them analytical skills necessary for graduate school and workplace success. The competitive application process annually selected four professors who each picked two collegians. The teams planned projects, developed theories, and co-authored published results.

The ability of scientists to tap grant money enabled them more effectively to involve greater numbers of undergraduates than their cash-strapped humanities colleagues. In 1993, the biology department won $550,000 four-year grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, which facilitated professors Aho, Pratt, Hanson, Van Amburg, and Nellermoe working with ten student research fellows. Regional community and tribal college and high school faculty also partnered in the summer projects. Chemist Darin Ulness later received a $532,380 five-year National Science Foundation (NSF) grant that paid for three student assistants, a post-doctoral fellow who did some teaching, and a laser laboratory for ultra-fast liquid molecule experiments. Ulness also garnered the $60,000 Henry Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar Award that hired an additional student for five summers. While collegians gained first-rate experience, physical chemistry and physics classes benefited from the new laboratory equipment. Some summers Biology might put fifty majors to work studying Costa Rican coffee plant fungus, Bangladesh hookworm vaccine, or dinosaur bones on Ron Nellermoe’s annual digs in South Dakota, Wyoming, or Montana.

Although I had worked productively with a student on the centennial history thanks to college funding, I did not envision how others might be engaged in future research in ways that guaranteed a successful grant application. In retrospect, I published and perished in a two-fold sense: First, the historical profession took little notice of my scholarship. Second, I did not take advantage of opportunities to better train undergraduates even though Bill Block credited the research we shared as most helpful for his professional success. Nevertheless, I soldiered on alone in pondering what my next task should be: Mid-20th Century Liberalism? The Culture Wars and American Higher Education? American Public Schools and Civic Education? A Fargo and Moorhead History? Being selected for a National Endowment for Humanities Seminar in 1992 settled the matter. Internationally known urban historian Olivier Zunz picked twelve applicants from Colombia, Madagascar, and different parts of the United States. We gathered at the University of Virginia, meeting in the Academical Village designed by Thomas Jefferson, ironically an archenemy of United States cities. Although the oldest, I knew the least. Listening as others shared their more advanced urban history projects and comprehensive knowledge for eight stimulating weeks facilitated my presentation of a thirty-five-page prospectus on the Northern Pacific Railroad and the founding of Fargo-Moorhead.

In Charlottesville, Jo and I sublet a retired professor’s lovely brick home while he summered in Connecticut. Besides paying modest rent, I mowed the lawn, put out garbage, and drove his car around the block weekly. Several oil paintings gave down stairs rooms a museum-feel so we mostly used the kitchen, study, and master bedroom. An unusually cool summer made air conditioning seem unnecessary until the cleaning woman complained about the heat. We then ran it on her days. We enjoyed seeing Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello on our walk down Rosser Avenue to the Alderman Library where I researched my project and read books assigned for the seminar. We toured the Shenandoah Valley and several historic sites on weekends. The lovely university town of reminded us of Iowa City. We often saw foreign films at a downtown theatre, browsed nearby used bookstores, and dined at a Greek restaurant.

Fifteen years passed before the University of Minnesota Press published Gateway to the Northern Plains. I worked on the book during two semester-long sabbaticals and every summer when time permitted. A South African Global Studies Seminar, a departmental self-study, several new teaching preparations, and Mother’s hospitalization and death extended the process. I researched at the Institute for Regional Studies (NDSU), Northwest Minnesota Historical Center (MSUM), and Clay County Historical Society. A 1995 trip took me to the McCormick Harvester Machine Company Collection at the Wisconsin State Historical Society; R. G. Dun and Company Collection at the Harvard Business School; Ada Louise Comstock Notestein Papers at Radcliffe College; and Thomas Hawley Canfield Papers at the Vermont Historical Society and University of Vermont. On other occasions, I examined the Northern Pacific Railway, Great Northern Railway, and Hill papers at the Minnesota Historical Society and James J. Hill Library as well as materials at the North Dakota State Historical Society and Montana State University.

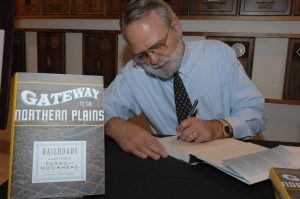

I started writing before finishing research because both advance best when carried on concurrently, as English historian E. H. Carr soundly advised in his seminal study, What is History? Three book chapters evolved from conference papers. “The Incorporation of America” and “Henry A. Bruns: Failed Frontier Entrepreneur” initially appeared in print as journal articles in North Dakota History and Minnesota History respectively. I did not submit “The Unhallowed Hollow: Prostitution in Victorian Fargo and Moorhead” for publication because too many journal articles can dissuade editors from doing books.

The University of Minnesota Press fortunately expanded its regional and railroad history list at this time. When editor Pieter Martin learned “The Unhallowed Hollow” was part of a book project, he asked to review the completed manuscript. Although Martin for the most part accepted the organization developed in my seminar prospectus, he wisely suggested more descriptive chapter headings and Gateway to the Northern Plains as the book title. Part I “Railroads at Red River” included three chapters: “At the Crossing: The Incorporation of Fargo and Moorhead,” “Booster Dreams: Henry Bruns and Moorhead’s Collapse,” and “Boomtown on the Prairie: Fargo Becomes a Gateway City.” Part II “In Pursuit of Vice and Order” had four chapters: “Old and New Americans: The People of Fargo and Moorhead,” “Domestic Virtues: Middle-Class Moral Order,” “Vagabonds, Workers, and Purveyors of Vice,” and “Building a Better Community: The Politics of Good Government.”

Geography and climate made Fargo and Moorhead small places. Temperature extremes, limited rainfall, and a short growing season discouraged settlers. Distant large metropolitan areas dictated high transportation costs to principal markets and prevented manufacturing growth. The coming of the Northern Pacific Railway Company in 1871 created the dual city where tracks spanned the Red River. During the next three decades railroads shaped Moorhead and Fargo economically, socially, and politically. While corporations and allied companies initiated settlement and fostered extension, local boosters and entrepreneurs aspired to make their city the “Gateway to the Northern Plains.” Small businessmen and corporate managers formed an uneasy partnership in which each needed the other to attain wealth. Yet their mutual pursuit of profits at times induced conflict as well as cooperation. Although the dual cities barely qualified as urban according to the U.S. Census, as commercial centers both connected the countryside with the outside world and advanced settlement of the Red River Valley and northern plains. They also shared a “metropolitan dream” of becoming places typified by industry, commerce, and urban services—electric lights, waterworks, streetcars, and daily newspapers.

As Northern Pacific advertisements throughout Europe and the eastern United States attracted prospective settlers to the region, dual city boosters and businessmen soon perceived the connection between rural settlement, urban population growth, and their own economic success. Hence, they welcomed most immigrant families of whatever cultural and religious background as being vital to their respective cities. American- and European-born joined in creating churches, lodges, and schools that fostered the hegemony of middle-class values. Vices associated with saloons, brothels, and gambling dens serving the migrant workers who congregated during the wheat harvest season offended the respectable middle class struggling to contain or eliminate their pernicious effects on the moral order. Bourgeois difficulties in distinguishing between the tramps they loathed and the harvest laborers they required complicated middle-class efforts at reform. Organized labor similarly challenged middle-class hegemony. Workers participated in the bourgeois moral ethos when they organized and acted like fraternal lodges. They undermined middle-class moral order, however, when they behaved like labor unions, adopted the strike as a weapon, and engaged in violence against property.

Municipal government evolved from “booster politics’ to “service cities” financed more responsibly. Boosters and businessmen dominated civic administration. They bridged the Red River and established rudimentary urban services to attract settlers and to promote economic development. Financial excesses and vice provoked middle-class reformers and businessmen to demand better government from mayors and aldermen who promoted fiscal responsibility, moral rectitude, and services that protected and promoted physical comforts of residents. By 1900, Fargo had become the distribution center for the region and both cities had well-established urban services, civic organizations, schools, and churches that supported the middle-class moral order and constrained lower class vice and disorder.

The handsomely produced book featured more than ninety photographs, images, and maps. It can be found in 860 World Catalog member libraries. Gateway received a glowing review in the Sunday Minneapolis Star Tribune, and favorable appraisals from Great Plains Quarterly, Lexington Quarterly, Annals of Iowa, Minnesota History, and North Dakota History. I pitched in on several promotional efforts: a Sunday Fargo Forum front-page article, “Fargo-Moorhead’s Most Influential Go Getters,” lengthy North Dakota Public Radio and Prairie Public Television interviews, two F-M Communiversity Courses, nineteen book signings and a dozen talks, as well as a Governor’s Day Conference Lecture at Bismarck and a Sesquicentennial Lecture at Concordia. While my inbred dullness did not me a successful promoter make, my efforts helped sell more than 1600 volumes before interest waned. Reviewers generally regarded it as well written, and one (perhaps delusional) called it “a brilliant model of local history.” Yet the Journal of American History did not consider it worthy of review although it is listed among recent publications. Apart from personal friend David Danbom citing it in his The Sod Busters, no other scholar to my knowledge has mentioned it in their bibliographies or notes. After I sent Richard White a copy, he graciously assured me: “I have used it quite fruitfully.” Perhaps the book served him as a doorstop because it is not mentioned in his seminal Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Building of Modern America.

The handsomely produced book featured more than ninety photographs, images, and maps. It can be found in 860 World Catalog member libraries. Gateway received a glowing review in the Sunday Minneapolis Star Tribune, and favorable appraisals from Great Plains Quarterly, Lexington Quarterly, Annals of Iowa, Minnesota History, and North Dakota History. I pitched in on several promotional efforts: a Sunday Fargo Forum front-page article, “Fargo-Moorhead’s Most Influential Go Getters,” lengthy North Dakota Public Radio and Prairie Public Television interviews, two F-M Communiversity Courses, nineteen book signings and a dozen talks, as well as a Governor’s Day Conference Lecture at Bismarck and a Sesquicentennial Lecture at Concordia. While my inbred dullness did not me a successful promoter make, my efforts helped sell more than 1600 volumes before interest waned. Reviewers generally regarded it as well written, and one (perhaps delusional) called it “a brilliant model of local history.” Yet the Journal of American History did not consider it worthy of review although it is listed among recent publications. Apart from personal friend David Danbom citing it in his The Sod Busters, no other scholar to my knowledge has mentioned it in their bibliographies or notes. After I sent Richard White a copy, he graciously assured me: “I have used it quite fruitfully.” Perhaps the book served him as a doorstop because it is not mentioned in his seminal Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Building of Modern America.

Gateway appeared in print soon after I stopped teaching as an adjunct professor at Concordia. Even before it was published, I visited the State Historical Society of Iowa archives in Iowa City and Des Moines to assess the viability of a third book project. As a child, I thought history was something that happened to other people. Yet studying my parents’ country school textbooks had become grist for my doctoral dissertation about public education and citizenship training. By that time, reading about the agrarian myth and McCarthyism made me aware of how my family had entered history. We still believed farmers were the backbone of the Republic, and talked with neighbors about whether communists had infiltrated the Elkader Public School. When an adolescent friend and I watched the Army-McCarthy hearings on TV, we rooted for the Wisconsin senator. My later reading of Ivan Doig’s This House of Sky, a memoir about growing up as a Montana ranch hand’s son, revealed how detailing ordinary lives could engage readers. Retiring from part-time teaching gave me more leisure to write about my boyhood.

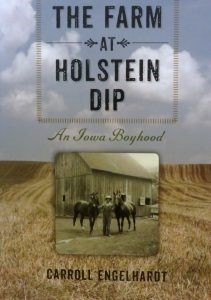

Lacking Doig’s literary skill, I researched the local newspaper as well as county, state, and national histories to set my reminiscences of a vanished rural way of life within the context of the technological revolution of American agriculture, the Second World War, the Cold War, and an emerging culture of affluence. Overcrowding and economic change pushed my ancestors from eastern Norway and northeastern Germany in the mid-19th century; abundant, fertile land pulled them to the Midwest. Finding what they came for in Clayton County, my great-great grandparents and their progeny farmed for the next three generations until the mid-20th century when the Second World War advanced an agricultural production revolution and integrated small towns and farms into the national economy, hastening the decline of small-scale diversified farms and main street merchants. When I submitted a manuscript to the University of Iowa Press, editor Holly Carver immediately expressed interest, helped me shape it into a book, and accepted the title my daughter Kristen suggested: The Farm at Holstein Dip.

Chapter One “Home” detailed how Mother’s hard labor as cook, cleaner, launderer, gardener, and chicken tender enhanced family income. She delivered me in the downstairs bedroom of a large white farmhouse that lacked electricity, plumbing, and central heat. Wartime profits improved our comfort with a new furnace and electric lights. Mother and most farm wives picked gas rather than electric ranges, yet bought electric mixers, steam irons, refrigerators, and vacuum cleaners as quickly as their budgets allowed. Chapter Two “Farm” described how Father planted crops of oats, hay (alfalfa, clover, and timothy), and corn in a five-year crop rotation cycle. Harvests fed cattle, hogs, and chickens that provided us milk, meat, and eggs for subsistence and market. A small herd of ten Guernseys yielded milk with high butterfat and a bimonthly check from the Farmers Cooperative Creamery. Skimmed milk mixed with ground feed made swill supplemented with several scoop shovels of corn fattened about one hundred hogs marketed each November. Like other farm families my brother and I did daily chores as soon as we were able.

Chapter Three “Town,” recounted Saturday nights when farmwives marketed eggs and bought groceries with the check. Men gathered to talk on sidewalks in summer and taverns in winter. Kids went to movies at the Elkader Theatre in all seasons. Merchants sought trade from a wide area, advertising specials in the Clayton County Register and opening on Wednesday as well as Saturday nights from May until September. “Bank Night” drawings filled the theatre for both shows. A lucky winner might receive $500. Elkader led the state in per capita retail sales during the Sixties even though its had fair folded and movie theatre struggled. Town population peaked at 1688 in 1980 before dropping in that decade’s rural crisis until it numbered just 1273 by 2020. As more people left the land, remaining farmers expanded acres, Main Street shriveled from three or four drug, grocery, and hardware stores as well as car and implement dealers to only one of each. The number of bars remained unchanged. Chapters Four “Church” and Five “School” respectively detailed my religious and secular educations at the Peace United Church of Christ and Central Community School.

I energetically promoted The Farm at Holstein Dip: An Iowa Boyhood with nineteen well-received talks and book signings at several libraries, three senior centers, a Moorhead Kiwanis Club, a Barnesville church, and Zandbroz Variety in Fargo. Only nine hundred volumes sold, perhaps because thrifty Iowans shared copies with friends and family. Although The Farm can be found in only five World Catalog member libraries, it is my most remarked upon book. More than thirty people sent congratulatory letters and notes, praising my well-written account that “brought back so many memories;” two blogged about it; and eighteen reviewed it for newspapers (2), historical and literary journals (6), and Amazon (10) where it garnered a 4.7 rating on a 5 point scale.

Yet Michigan novelist Timothy Bazzett scathingly dismissed The Farm in an Amazon review as “painstakingly documented … [and] disappointingly dry.” Though informative, it reads “like a doctoral dissertation: scholarly … and utterly devoid of humor.” My “professorial style” had hidden my excitement at coming of age. Bazzett clearly had not milked cows by hand or cleaned barns on winter mornings. Nor was the book inaccessible to nonacademic readers. Aunt Betty said simply: “You told it like it was.” John, a classmate, called it “The best book I ever read.” Corene, a childhood neighbor, proclaimed it “so good!” Bazzett violated the book reviewer’s first commandment when he criticized me for doing a poor job on a book I did not chose to write. He did not perceive how I had composed a social history of rural America at midcentury through the lens of my family’s experience. Minnesota, North Dakota, Nebraska, and Wisconsin readers identified with the Iowa rural way of life I had described. The State Historical Society of Iowa vindicated my approach with the 2013 Benjamin F. Shambaugh Award for “the most significant book on Iowa history published during the previous calendar year.” The prize was particularly sweet because my mentor Stow Persons had been similarly honored twenty years earlier for The University of Iowa: An Institutional History.

Two new book projects occupied me into my eighties. Shortly after I published Gateway to the Northern Plains, history colleague and Probstfield Living History Farm Foundation board member Gretchen Harvey told me: “You should write about Randolph Probstfield.” A decade later I started research and eventually completed manuscripts about the Probstfield family and a memoir tentatively titled Schooling. COVID complicated finding a publisher for the Probstfield volume. Finally, I gave up on academic publishers after two rejections and another press sitting on it for twelve months. Mortality concerns compelled me to self-publish By the Sweat of His Brow and deposit Schooling at the Concordia College, University of Northern Iowa, and University of Iowa archives. Happily, I lived to see the former in print.

Despite a positive Kirkus and two state historical journal reviews, two favorable local newspaper notices, several speaking engagements, many more occasions peddling at Vendor’s Fairs, and a more than a year of social media marketing efforts, the book can be found in only seven World Catalog member libraries (almost all local) as well as the Libraries and Archives of Canada. Only 502 copies have sold, confirming the University of Minnesota and Minnesota Historical Society presses assessment that family biographies will not sell. By the Sweat of His Brow is a heart-breaking and heart-warming Great Plains settler narrative well documented from a daily journal, family letters, and photographs. Randolph defied his Catholic parents and refused to become a priest, emigrating from the Rhineland to the United States in 1852. He eventually married Catherine Goodman and became pioneer farmer on the Minnesota side of the Red River. Together they accumulated 1100 acres of prime farmland and created a loving family of eleven children. The family farmed at Oakport for nearly a century through three generations. Randolph pioneered truck farming in the Red River Valley, selling vegetables to railroad construction crews, shipping onions by railroad to Bismarck and potatoes by steamboat to Fort Garry, Canada, and becoming known statewide for experimenting with fruit and vegetables to learn which grew best in northern Minnesota.