3 Iowa Graduate School Grind

The Old Capitol and Pentacrest, perched on a steep hill overlooking the Iowa River, are long-standing Iowa City landmarks. The General Assembly consigned the beautiful Greek revival structure and land to the university in 1857 when it moved the state capital to Des Moines. Jefferson, Madison, Washington, and Clinton streets on the North, West, South, and East in that order enclosed the core of the municipal street grid. Four Beaux Arts buildings—inspired by Classical architecture the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair popularized—eventually flanked the Capitol: Schaeffer Hall (1902), Macbride Hall (1908), MacLean Hall (1912), and Jessup Hall (1924). For the next five years my existence centered on this idyllic setting. The History Department occupied Schaeffer, delivered Western Civilization lectures in Macbride Auditorium, and allotted Teaching Assistant (TA) offices in Gilmore Hall on the northeast corner of North Capitol and East Jefferson streets. Bookstores, movie theatres, bars, and eateries occupied blocks east of Clinton. The Main Library and Memorial Union stood west of Madison near the river on the corners of Washington and Jefferson respectively.

The prestige of American higher education peaked in the early Sixties. Political and corporate leaders considered universities the national nerve center for research and innovation even as most minimized undergraduate teaching and learning. Howard R. Bowen—an economist known for his research on learning investments and the social benefits of an educated citizenry—became Iowa’s president in 1964 after nine years as head of Grinnell College, an esteemed liberal arts school. He initiated a faculty senate to engage professors more with the university. He backed student housing and activities organized on a human scale to preserve and develop individuality. He presided over creating a Commission on Human Rights, a counseling office for minority students, an Afro-American Center, and an Afro-American Studies program as well as recruiting more women and African Americans. Enrollment grew from 14,500 to 19,500 and new construction boomed. Bowen’s challenges to conventional administrative wisdom ended the somnolence that had characterized the twenty-four year tenure of his predecessor, Virgil Hancher. Despite a sterling record, Bowen abruptly resigned in spring 1969 perhaps persuaded by escalating student-led anti-war protests and his wife’s worries about violence.

Innocently unaware of impeding radical changes the Sixties would bring, Jo and I packed a U-Haul trailer and moved in August to a furnished two-room apartment on the first floor of a ramshackle house containing a warren of nine units at 407 North Dubuque Street. We stepped down from a hallway door just inside the front entrance into a living room separated from a bedroom by a kitchen alcove equipped with a stove, sink, and refrigerator. An adjacent cramped bathroom had a shower and stool on which while sitting one’s knees touched the wall. Opposite the alcove, a small dining table blocked another door to a driveway reserved for unloading groceries or other goods. We paid $82 monthly for a smaller yet nicer place than our previous dump and an additional $8 for a garage in the next block. Jo once more washed and dried clothes at a nearby Laundromat. She began teaching physical education at three elementary schools a few weeks earlier than the university fall term started in mid-September.

Meanwhile, I finished revising “Reinhold Niebuhr’s Theology of History” and sent it to Dr. Harold Wohl for his approval. Because the thesis had not been submitted formally to SCI, I did not earn a Master of Arts degree. Friend Tom Bruce often teased me about being a B.A. plus thirty and finally 109 hours. Such a credential would not have attracted many job offers. With thesis done, I explored downtown bookstores. The paperback revolution spawned by Penguin, Mentor, and other imprints in the Thirties and after made available inexpensive editions of many titles an aspiring historian thought essential to own. I would spend $1326 as a graduate student building a professional library. When a monthly bill topped $57 in 1966, Jo angrily condemned my spendthrift habits, reducing my subsequent spending by nearly half. I also bought pipes, tobacco, and other accessories at Smoker’s Cove enabling me to play “pretend professor.” Her wedding gift of a briefcase furthered my self-delusion.

History Studies and Struggles

The Iowa History Department grew into a well-regarded program after “the Revolution of 1947” elected William O. Aydelotte to succeed the recently deceased chair. Winfred Root had ruled after Arthur Meier Schlesinger decamped for Harvard University in 1925. His own and the department’s scholarship subsequently withered. In marked contrast, Aydelotte set aside faction, fostered collegiality, and built scholarly excellence. An Iowa’s dean quipped: “He always wanted to hire Jesus Christ; failing that, he preferred one of the twelve apostles.” Notable hires included Latin Americanist Charles Gibson, Russian historian Nicholas Riasanovsky, and American intellectual historian Stow Persons. The latter left more prestigious Princeton because Iowa gave him the opportunity to develop his own program of teaching and research. He later learned Aydelotte had ranked him a lowly fourth among the apostles. Allan Bogue (1952-1964) and Samuel Hays (1953-1961) joined in creating the Iowa School of Quantitative Studies founded on Aydelotte’s Law: “All generalizations are quantitative.” Several of its graduates achieved distinction: Joel Silbey, Cornell University; Robert Swieringa, Hope College; Samuel McSeveny, Vanderbilt University, and Robert Dykstra, Iowa and SUNY-Albany. The department brought Dykstra back to teach American social history. Graduate student Russell Menard assisted him in teaching the first African-American History course at Iowa in 1968-1969. Dykstra’s peers had earlier elected him the first president of the Graduate Historical Society that the department had founded to give students professional development opportunities and a voice in governance.

Eighteen professors and twenty-three TAs comprised the male dominated department. Rosalie Colie held a joint appointment in English and History from 1963 until 1966. Although historians and students welcomed Colie, her criticisms outraged English colleagues who drove her to Yale. Four female TAs claimed to have been well treated, yet more stridently demanded changes as the decade progressed and their numbers increased. University administrators dictated appointing the next female in 1971 over considerable departmental opposition when the Medical School wanted to hire her husband who would not come unless his wife was given a job too. Ironically, Linda Kerber proved outstanding and achieved rock star status as president of the Organization of American Historians (1996), American Studies Association (1998), and the American Historical Association (2006). Ten other women and three Blacks were hired during the next twenty-five years. African American scholar Wilson Moses came with Kerber, but departed in 1976 after receiving his Ph.D. from Brown University. White male political radicals had been courted earlier. While President Hancher vetoed the appointment of Ray Ginger, the biographer of American Socialist Eugene Debs, President Bowen did not block Staughton Lynd (who rejected the offer) or Sydney James, a former communist (who accepted). During the Fifties and after, the department prided itself on being faction-free even though one member given to hyperbole claimed “the Jewish mafia” dictated its actions.

The doctoral program mandated ninety credits with thirty and twelve hours respectively earned in a major and cognate area; French and German language reading proficiency; five research seminars, five comprehensive examinations, historiography and philosophy of history courses, and a successful oral defense of a written dissertation. SCI gave me a good start on clearing these hurdles. I transferred thirty credits, including two seminars; learned sufficient French to readily pass the reading examination in October; studied Reinhold Niebuhr as a possible dissertation topic; and earned credits in three of the five examination fields I would select: American Intellectual History, American History in the Middle Period, 1789-1877, and Modern European Intellectual History. At Iowa, I began preparing Recent American History since 1877 with Christopher Lasch the first year and Religion in American History as an outside area with Sidney Mead the second. The latter choice initially provoked grudging approval from graduate advisor Alan Spitzer because the courses were cross-listed in both religion and history.

As a TA, I earned $2250 for a two-semester course in Western Civilization from 1500 to the Present. Departments assigned professors to lecture twice weekly as “sage of the stage” while graduate students led discussion sections two other days. First year core courses thus arranged fostered passive, impersonal leaning and typified university indifference for undergraduate education. The Iowa sages were two recently hired European historians. I worked with Russian specialist Patrick Alston who lectured to seven hundred freshmen in Macbride Hall Auditorium; TAs sat at the back of the balcony and recorded his wisdom. Each TA taught three sections, enrolling twenty students one year and thirty the next. Whether Alston’s winging it with unprepared big picture lectures complicated or simplified the TA’s task depended on whom one asked. Europeanists dismissed Alston’s handbook outlining the major trends of Western Civilization as a “pile of crap.” As an Americanist and licensed social studies teacher, I found it pedagogically useful for instilling generalizations and concepts. We rarely met as a group and never discussed at length how textbooks or subject matter might best be taught. No one supervised or assessed our performance. I complained, arguing the system denied both graduate and undergraduate students full educational value. Training would better equip TAs for future careers and improve instruction. These lamentable conditions persisted at Iowa even after the Seventies job market collapse initiated changes elsewhere. In 1970, supervised teaching was rejected. No professors wanted it and TAs prized their independence. The department did not adopt class visitation until 1993.

Each term Professor Alston assigned three paperbacks and R. R. Palmer and Joel Colton’s highly praised and sophisticated textbook, A History of the Modern World. Joseph Strayer’s Western Europe in the Middle Ages was short, readable, and perceptive. R. H. Bainton’s Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther was accessible, detailed, and longer. B. H. Sumner, Peter the Great and the Emergence of Russia was detailed, dull, and shorter. These texts were more teachable than those assigned for the second semester. Harold Nicholson’s The Congress of Vienna represented the dullest form of diplomatic history. Isaiah Berlin’s Karl Marx was a classic yet demanding text. Albert Schweitzer’s interesting Out of My Life and Thought seemed to me too far removed from the major twentieth-century trends of Western Civilization. Teaching these texts in ways that engaged freshmen demanded a lot of preparation. Rumors circulated that others did not take this work as seriously as me.

TAs had offices on the remodeled fourth floor of Gilmore Hall. I shared mine with three Europeanists. Two were writing their dissertations. Ron promised to have my wife and me over for dinner, but regrettably never did. I would like to have known him better. Keith invited me for a beer, and drove us to the bar in his Jaguar. It has been my only ride in one. Steve, a newcomer, talked so much that I used the office only for meeting students although few appeared. Older colleagues directed me to the graduate study area on the third floor of the Main Library where I was assigned a desk and a footlocker for storing personal items. The three glass-enclosed rooms seemed like a zoo to some. It is an apt analogy. The long hours spent there made many of us feel confined and on display. The area had been segregated by design from the noisy study hall atmosphere on the second floor where undergraduates gathered and performed primitive mating rituals. When patrons entered the library on the north side from Washington Street, the observant might note nine panels over the entrance drawn by well-known Des Moines Register cartoonist “Ding” Darling depicting the evolution of humanity from cave men to in-one-ear-and-out-the other students of the present. Five display cases in the main lobby featured exhibits that were changed monthly throughout the year.

The relatively new Main Library, dedicated in January 1952, had been designed for modular construction over an extended period of time. South side additions built in 1961 and 1965 increased usable space to 200,000 square feet. The final phase completed in 1972 almost doubled the library’s size by adding two floors and a south entrance. As a graduate student, I immediately appreciated having access to a much larger book collection than had been available at SCI. Air conditioning if it worked made the building a comfortable place to study during hot, humid Iowa City summers when the state’s thousands of acres of famed tall corn was growing. Coffee breaks or lunches at the Memorial Union just two blocks away were an important feature of history graduate student life. I relied on these occasions for a break and an opportunity to learn more about the historians’ craft from my more experienced peers.

TAs typically carried nine credit hours each term. I signed up for just eight because part-timers paid substantially less tuition and married men still had draft deferments. By fall 1965, the Vietnam War eliminated this exemption and compelled me to enroll for the nine credits needed for a student deferment until the 1967 fall term when I had completed all course work and celebrated a twenty-sixth birthday that theoretically made me too old for the draft. Similar circumstances did not spare my talkative office mate. His Missouri draft board took him; he fought in Vietnam until the army utilized his historical skills interviewing others about their battle experiences. In registering for courses, I followed Professor Wohl’s excellent advice: “Audit undergraduate lecture courses and take those limited to graduate students for credit. Some of my peers adopted this plan the second semester. Unfortunately for me, rigorous writing assignments exposed my weaknesses and compromised my academic standing. For the next several terms it became a question whether I could improve quickly enough to stay in the program. Older TA friends said: “You should not have taken such demanding courses.” Yet I enjoyed my choices and learned a lot.

Persons held a relatively rare Research Professorship, taught just two courses each term, and earned the highest departmental salary, $12,000. At the exact moment his American Intellectual History lecture class was scheduled to begin, he entered the classroom, placed a pocket watch on the lectern, opened a file folder, and began speaking from five x eight-inch note cards. One wag maintained that he had just five cards and the fifty-minute period ended when he finished the last one. He had authored the assigned textbook to define the field of study—American Minds: A History of Ideas. His lectures were based on research for a book that Columbia University Press published in 1973: The Decline of American Gentility. When talking about this project, he once said, “Daniel Boorstin’s The Americans is a history of mass society. I am working on an intellectual history of mass society.” This sounded imaginative, ambitious, and exciting to me. Sadly, the book did not achieve the fame I had anticipated or the sales Boorstin enjoyed. While auditing Stow’s lecture course, I also enrolled for credit with a dozen or so others in his colloquium, Readings in American Intellectual History. It met weekly for two hours. Each of us selected a book from his comprehensive examination reading list and in turn made eight or so brief reports during the semester. Upon request, Stow distributed another list of historiographical books and articles. The class helped me learn the field’s basic bibliography and later proved useful in my own teaching.

A short, thin, taciturn New England Yankee, Stow invariably kept his comments brief. While he said a lot in few words, I required more expansive remarks. Diffidence did me in with him and other professors. If I had been more assertive in asking questions about what I didn’t know, my graduate studies might have been more fruitful. Inexperience and lack of confidence kept me from getting the help I required. This first became evident when I asked Stow about taking Reinhold Niebuhr for a dissertation topic. He cryptically replied: “Sidney Mead might be more helpful to you on that subject.” Since I did not yet know Mead, and had come to Iowa expressly to work with Persons, I meekly took his reply as a no and started casting about for another topic. In retrospect, I should have thought more about how Niebuhr typified mid-twentieth century American Cold War liberalism and prepared several propositions about how Niebuhr’s religious and political ideas might be developed into a dissertation. Not engaging Stow, Christopher Lasch, or Sidney Mead on these topics extended my Iowa graduate studies one year or more, and damaged my subsequent professional career.

Recent American historian Christopher Lasch turned out to be the most intellectually stimulating professor I would ever have. I audited his course on American Progressivism, 1890-1930, and enrolled in his Twentieth Century American Social Theory Seminar. He said nothing about Populism and little about Progressivism. He instead lectured from page proofs of his soon to be published book, The New Radicalism in America, 1889-1961: The Intellectual as a Social Type. It was heady stuff. He critiqued the “new radicals” for failing to remain detached and becoming overly committed to political causes. I might have used his critique as the historical context for writing a dissertation about Niebuhr if I had been sufficiently insightful to grasp the possibility. Lasch also discoursed about Jane Addams and Mabel Dodge Luhan, the only women I recall learning about at Iowa. His lectures dovetailed with the seminar. In two-hour sessions we wrestled with twelve books written by progressive intellectuals John Dewey, Walter Lippman, and Randolph Bourne as well as more contemporary thinkers C. Wright Mills, John Kenneth Galbraith, and Herbert Marcuse.

Lasch incisively critiqued my written work. He characterized my interpretive essay on five authors as “a good paper marred by a certain lack of clarity and a certain vagueness in the argument.” He rejected my claim social Darwinism distinguished Thorstein Veblen and E. A. Ross from John Dewey, Walter Lippmann, and Randolph Bourne. All emphasized changes in the environment and all were to a certain extent determinists. He praised my hard work and the excellent annotated bibliography I had prepared for the forty-six-page tome on “The Evolution of Walter Lippmann’s Political Theory, 1912-1937.” Unfortunately, my essay suffered from “a great deal of very muddy writing and an unnecessarily abstract approach.” I should have invented new analytical categories and clarified his ideas about “fear of the state” and “concern for personal liberty.” To determine Lippmann’s suitability as a dissertation topic, I should examine secondary sources. Correcting previous interpretations would justify a proposed study. One also might compare and contrast Lippmann’s “ideas about free enterprise with the system of very unfree enterprise which was developing at the time.”

Rereading Lasch’s comments today as a published author and retired history professor, I am impressed by how perceptive they are. No one else in my graduate studies ever gave me so much helpful advice on my written work. Yet his words devastated me at the time. Not knowing how to turn his helpful criticisms to my advantage, I dropped Lippmann as a possible topic. When I solicited Lasch’s advice on how to write better, he was sympathetic to my plight and loaned me his Harvard Handbook for Freshmen English. While examining it did not much benefit my writing, the experience did put me the closest I would ever come to an Ivy League education. Several additional critiques of my misdirected essays were required before I learned how much effort and polishing were needed to make my prose readable. As a seasoned scholar who spends hours rendering words, I am amazed at how much editors still find to correct.

The required two-credit historiography course taught by Professor Alston disappointed me the most. He did not prepare any more thoroughly for it than he did for Western Civilization. Still, he assigned several classic interpretive texts written by eminent historians: Henri Pirenne, Medieval Cities: Their Origins and the Revival of Trade, Johan Huizinga, The Waning of the Middle Ages, Jacob Burkhardt, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, and several others. He gave groups the task of explaining each text and its significance to the rest of the class. While I enjoyed the reading, presentations varied in quality from dismal to decent. Ours on Lewis Namier, 1848: Revolution of the Intellectuals rated better than most in my humble opinion. For the assigned paper, I wrote on “The Problem of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Presidential Leadership,” surveying interpretations by Rexford G. Tugwell, Richard Hofstadter, James McGregor Burns, and Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. Lasch dismissed my effort as “OK, but still not awfully inspiring.” To spare my feelings, he added: “Perhaps it is the subject.”

Besides auditing second term lecture courses on American Intellectual History since 1865 and Modern European Intellectual History, I enrolled for eight academic credits. My writing misadventures continued for Stow’s American Intellectual History Seminar and Individual Study in American Middle Period, 1789-1840, with Professor Malcolm Rohrbough. Persons sharply criticized my seminar paper on “Leonard Brown: A Study in Populist Thought” for its poor writing, opaque language, and insufficient focus on Brown’s ideas. After Lasch penalized me for not consulting secondary sources about Lippmann, I overcompensated by commenting extensively on the debate between Norman Pollack and Richard Hofstadter about the meaning of Populism. I was a long time learning how to synthesize and analyze properly a wide range of research materials, Stow did not rule out Brown as a dissertation topic. In determining sufficiency of sources, I could rely on publications as well as personal papers. Brown could be used to explain why Iowa had less Populism than its Dakota neighbors. Noting the differences between Unitarianism and Universalism would help me get at his religious ideas. Yet Stow closed on a discouraging note. He could not give me much advice because he had not studied Populism. Surprisingly to me, he did not bother commenting on my Individual Study essay, “The Meaning of progressivism: An Interpretive Essay of Ten Books.” Had I chosen Niebuhr as a topic for both Persons and Lasch, and combined these papers with the thesis I had written for Wohl, I would have had a substantial start on a dissertation and might have graduated one or two years earlier than I did.

Professor Rohrbough, an affable newcomer, became in time a departmental mainstay who published several notable books about the American West. He dismissed my interpretive essay about fifteen books selected from his comprehensive examination-reading list as “a generally adequate outline of the contents of these books without attempting to go more than skin deep.” In analyzing Jacksonian Democracy, I should have addressed in more detail the period’s economic and constitutional developments, the Jeffersonian roots of Jacksonianism, and the interpretations put forward by George Rogers Taylor, Richard Hofstadter, Glyndon Van Deusen, Marvin Meyers, and Lee Benson. He also marked numerous word choice and syntax errors, demonstrating once again how much my writing needed to improve.

When financial aid letters were mailed in February, the graduate grapevine reported the faculty had been disappointed with the poor quality of students (like me) recently selected for the program. Devastated by non-renewal, I promptly threw up. After recovering, I screwed up my courage and breached etiquette by calling History Chair Charles Gibson at home. Fortunately, the eminent Latin Americanist was a kindly man. He politely explained that I was still under consideration and might have my teaching assistantship renewed, which it was in May. Had it been delayed until after second semester grades were posted, the letter might not have been sent. I had dropped below the department’s 3.50 grade point average required for retention. If “Bs are like Fs,” as Ann Leger (another Persons student) maintained, then I was failing. How could I work harder than sixty hours weekly? How could I improve my writing and show I belonged? It seemed I already had three strikes. David Tucker—a highly regarded soon-to-graduate Lasch student—persuaded me I had been victimized more by my own bad decisions than lack of ability. Even he had been hindered in his job search by his mentor’s “damning with faint praise” recommendation. Lasch agreed to rewrite the letter when confronted. Tucker soon landed a job at the University of Memphis. Despite being deeply discouraged and guided by David’s counsel, I rejected an opportunity to enter the Peace Corps, which pleased Jo, and committed myself to another year at Iowa determined not to let the bastards get me down.

Assorted diversions had eased academic pressures throughout the year. History graduate students played touch football on fall Friday afternoons on the Women’s Athletic Field south of the Memorial Union and basketball on winter Monday mornings at the Iowa City Recreation Center. A few reprobates occasionally stopped for a beer or two at one of the several student bars after leaving the library at ten o’clock. The Graduate History Society met occasionally at the downtown Methodist Church for talks by professors accompanied by refreshments. Jo and I attended Hawkeye football games even though Coach Jerry Burns failed to perpetuate the Forest Evashevski glory years. “Burnsie” became known as “the chemist” because he turned good players into bad ones. We often went to matinees at downtown movie theatres preceded by early suppers at the Hamburg Inn. Such feel-good features as Mary Poppins and A Thousand Clowns in subsequent semesters lifted my spirits when I needed it most. We hosted a Thanksgiving Day dinner for several people, serving ham without considering the Jewish prohibition against eating pork. Viewing a similar scene in Woody Allen’s Annie Hall still causes me to cringe. We occasionally socialized with other couples over wine and spaghetti dinners without developing the close friendships we had enjoyed at Cedar Falls. Our first Iowa City year was a lonely time for both of us.

During the summer, we moved six blocks east to a larger, nicer furnished downstairs apartment in a smaller house at 323 North Lucas Street. Fellow historian Frank Burdick and his wife Angela lived upstairs. The birth of their first baby ended the occasions we socialized with them. When he returned to teaching at SUNY – Brockport the following summer, historians Tom Schlereth and Jim Hamilton, an ISTC friend, moved into their apartment. We did not mind paying $100 monthly for three big rooms and a bath, utilities included. I sometimes read on the front porch and often grilled in the back yard. For a bedroom study, I put a door on top of a pair of two drawer file cabinets for a large desk, attached the florescent lamp previously acquired in Cedar Falls that I kept for sixty years, placed an old Underwood typewriter Jo’s parents had given us as a wedding present on a small table beside the desk, and acquired a well-used office chair. My professional library filled two bookcases supplemented with bricks and boards.

Fortunately for my badly bruised ego, I had a productive summer session, enrolling in Recent America, 1877-1914 and German PhD Reading I, the first step toward completing my second language requirement. Christopher Lasch’s lecture course gave me a highly critical assessment of United States history. He assigned several stimulating books that I thoroughly enjoyed. Matthew Josephson’s The Politicos showed how industrialization corrupted politics and politicians. C. Vann Woodward’s Tom Watson explained how conditions in Georgia transformed Watson from an agrarian radical to a racist senator. In The Uprooted, Oscar Handlin theorized that the disruptive immigration process quickly destroyed traditional immigrant values. Twenty Years at Hull House, Jane Addams’ autobiography describing her work in a Chicago slum, suggested several ways Handlin got it wrong. With no paper to bring me down, my exam-taking skill elevated my grade point average above the department’s minimum for retention.

Jo rejected my urging her to continue the master’s degree she had begun the previous summer at SCI. She decided Iowa graduate school would be too tough for her after watching my frustrating yearlong struggle. Instead, she took assorted summer jobs for the next four years: swimming teacher at the Iowa City Pool; lifeguard at the Iowa City Recreation Center; and youth recreation director at the University Speech and Hearing Clinic. In August we took a belated two-week honeymoon trip to New England. We visited Jo’s sister and brother-in-law in Danville, Indiana, as well as my former SCI dormitory director Sandy MacLean and his wife at the University of Indiana. While swapping doctoral studies war stories, I disturbed him by relating leftist teachings imbibed from Lasch. I never heard from him again. After departing Bloomington, we made our way to upstate New York, visiting Fort Niagara and numerous fruit stands before driving through the Adirondacks to Fort Ticonderoga. We followed the lovely Connecticut River Valley northward and eventually reached the Maine seacoast, where we celebrated our second anniversary with a lobster dinner. Sadly, we left most of it on our plates because we were too timid to ask for instructions on how to extract the meat. We visited Harvard, the USS Constitution, and the Freedom Trail in Boston, Plymouth Plantation, and Cape Cod before stopping at the Gettysburg Battlefield on our way back to Iowa. With gasoline at 26 cents a gallon and motels averaging $10 each night, the $26 we paid at a Holiday Day Inn near Harvard seemed extravagant. We traveled in a 1958 Chevrolet, acquired the previous year for $850 and the trade-in of our 1952 Chevrolet. It burned one quart of oil every 500 miles. At that rate, an oil change did not seem necessary.

The New England trip renewed my energy for facing the challenges ahead. I returned home determined to make a new beginning and succeed in my studies by working longer hours at a new office with new mates on the second floor of Gilmore Hall. Russian historian Donald McIntyre served as History Chair William Aydelotte’s administrative assistant while writing his dissertation. English historian Jim Hamilton and I taught Western Civilization and took courses for our comprehensive examinations. Latin American historian Wayne Osborne showed up only for office hours, leaving the rest of us to spend most of our days, nights, and weekends toiling together for the next nine months. One or two of us occasionally ended our work day by stopping at Donnelley’s—a working class bar on Dubuque Street that had become the history graduate students’ “watering hole” of choice. At times, we went to Bernie’s Foxhead because fewer patrons ensured easy access to the pool table. Initially, Jo seemed comfortable with my study habits and recreational choices. Her own work duties had changed for the better. She was glad to be relieved from the tedious task of High School Girls Drill Team Coach and to be assigned as the Roosevelt Elementary School physical education instructor rather than traveling between three institutions. She flourished at Roosevelt, making friends and winning the kids’ affection for making gym fun. An appreciative principal nominated her for the SCI Women’s Physical Education Department Wild and White Award. This well-deserved recognition of her excellent teaching made me very proud.

While I struggled to meet Iowa’s academic demands, the department faced difficulties of its own. Charles Gibson (Latin America), Robert Kingdon (Reformation), Rosalie Colie (Early Modern European Intellectual History), and Christopher Lasch (Recent America) departed in that order for greener academic pastures at Michigan, Wisconsin, Yale, and Northwestern. At the same time, Patrick Alston (Russia) and Ulrich Trumpener (Germany) did not get tenure. His remaining colleagues again tasked William Aydelotte (Modern England) with program rebuilding. Aydelotte resented how other programs poached faculty he had hired. “They don’t need to do painstaking searches,” he once bitterly complained. “They just look to see who is teaching at Iowa!”

Despite publishing very little of his path breaking quantitative history studies of the British Parliament, Aydelotte had a distinguished academic reputation. The National Academy of Science honored him as the first historian elected to membership. Aydelotte epitomized the absent-minded professor. A fellow student, who observed him putting money into a parking meter, waggishly remarked, “It was like they had been introduced for the first time.” As the son of eminent educator Frank Aydelotte, Swarthmore College President (1921-1940), and Marie Jeannette Osgood, daughter of an internationally known musician, he grew up meeting many famous personages in his family home. Given this background and remarks like “Proust is best read in the original French,” many of us wondered whether he fully comprehended our midwestern cultural deficiencies. I enjoyed his carefully prepared and delivered Modern European Intellectual History lectures and how well he conducted the required Philosophy of History course. On the other hand, his direction of Individual Study Readings angered me. He terminated our conversation about a dozen books after asking only three or four questions. I did not think fifteen minutes sufficient to show what I had learned. Diffidence did me in again; I had not told him all that I knew, and I did not protest what I considered an unjust outcome.

A second year teaching Western Civilization gave me greater satisfaction even though grading three sets of blue book examinations each term took longer when larger sections boosted our total load from sixty to ninety students. Alston replaced the substantive Palmer and Colton text with the more accessible two-volume paperback Modern Europe by Peter Gay and R. K. Webb. I especially liked how Gay, an intellectual historian, emphasized the role of ideas in history. When I shared these opinions with Gilbert Allardyce—a former TA who became a distinguished scholar of Fascism and an outstanding teacher of undergraduates at the University of New Brunswick—he rudely dismissed the textbook as “that rag.”

The “grind” of German PhD Reading II posed my toughest challenge. Sixty people started the course and twelve finished. Our teacher—“a crazy Brit” who looked like comedian Terry Thomas—gave us long German passages to translate from the literary and technical readers. We were additionally responsible for twenty pages from a German book in our field of study. Like my Americanist contemporaries, I used The New History of the United States written by French author André Maurois in English and then translated into German. Aided by this “pony” as well as lots of blood, sweat, and endless hours of mindless toil I demonstrated a reading knowledge of German on February 1, 1966. It was the most senseless educational exercise of my life. When I mentioned it to Aydelotte, the former Harvard Classics major could not comprehend my negative attitude about required language study for historians.

Besides clearing the German hurdle, I earned eighteen credit hours and boosted my cumulative grade point average to 3.68 thanks to writing better. “Moralism in American Life, 1830-1877,” a paper written for Individual Study with Rohrbough, demonstrated that I had finally learned how to craft an expository essay, something any worthy undergraduate should be able to do. Rohrbough’s succinct comment, “Good—I like this,” spoke volumes on how far I had progressed from the previous year. By focusing on “moralism,” I managed to incorporate books about social reform, public education, slavery, anti-slavery, conservative ideology, and southern nationalism. I cited Alice Felt Tyler’s Freedom’s Ferment, Ruth Miller Elson, Guardians of Tradition: American School-Books of the Nineteenth Century, Stanley Elkins, Slavery, Gilbert Hobbs Barnes, The Anti-Slavery Impulse, David Donald, Charles Sumner and the Coming of the Civil War, Thomas Pressly, Americans Interpret Their Civil War, Kenneth Stamp, The Era of Reconstruction, and Robert Green McCloskey, American Conservatism in the Age of Enterprise.

Sidney Mead’s Religion in American History—a two-semester lecture course—proved highly rewarding. His personal warmth fully engaged students. He claimed to learn more from talking with undergraduates because they had wider interests than graduate students. His remark did not offend me because my obsessive, neurotic behavior confirmed its validity. Mead assigned his seminal book, The Lively Experiment: The Shaping of Christianity in America, and a recent, standard textbook: H. Shelton Smith, Robert T. Handy, and Lefferts A. Loetscher, American Christianity: An Historical Interpretation with Representative Documents, Vol. 1: 1607-1820 and Vol. 2: 1820-1960. To evaluate the work of graduate students, Mead posed three or four questions and invited us to respond in typed midterm and final papers. My cogent essays fully engaged the questions and totaled thirty-five pages with citations to documents from Smith, Handy, and Loetscher, several professional journal articles, and numerous secondary works by Perry Miller, Edmund S. Morgan, and others from my own professional library.

For the second semester, Mead waived the examinations and had me research, write, and deliver a lecture on a topic of my choice. “Conceptions of the Common School: Iowa, 1856-1858” was the result. Mead declared that it had “much promise” as “a prospectus” for my dissertation. My fourth attempt at defining a topic emerged from reading Mead’s Lively Experiment and the serendipitous discovery of Bernard Bailyn’s Education in the Forming of American Society: Needs and Opportunities for Study. Mead suggested that public schools had become the established church of an emerging secular, highly mobile society. Americans made education the main institution for articulating and instilling the core values that preserved social cohesion and prevented fragmentation. Bailyn claimed that attention to formal education increased in the nineteenth century as the family’s traditional effectiveness declined. It assumed new importance in every region as frontier settlement moved ever westward, threatening inherited culture, expanding social mobility, and making the creation of a genuine community difficult. Public schools thus furthered the national interest by articulating and transmitting social beliefs that unified a disparate people.

Despite my improved academic performance and good progress toward completing a degree, the department again excluded me from financial aid. Not surprised at being disregarded, I neither threw up nor called Aydelotte for an explanation. I moved out of my Gilmore office in June and began preparing for comprehensive examinations scheduled in January. When belatedly offered an assistantship in late August, I refused to have more time for study. Lasch’s departure meant that newly appointed Professor Jerome Sternstein would administer the Recent America field examination. To prepare, I audited visiting Professor Paul Glad’s summer lecture course on Recent American History, 1914 to the Present, which offered a less-leftist perspective. In the fall semester, I enrolled for credit in Sternstein’s Populism and Progressivism, audited his Recent America, 1877-1914, and took Readings in Religion from Mead and his Genius of American Religious Institutions to complete the twelve credits required for my outside field.

History graduate students had put together a file of past examination questions. Each of us updated it and passed it on after we had run the gauntlet. Review involved going over lecture and reading notes I had taken or transcribed from others. I did this at home during the day and the library at night until it closed at midnight. Too nervous to sleep, I tried to relax by drinking hot milk and reading Sinclair Lewis novels: Babbitt, Arrowsmith, Elmer Gantry, and Dodsworth. Slumber often did not come until four o’clock. I rose at eleven, attended class, and studied some more. On Friday nights, Craig Lloyd, Billie Jeanne Hackley, English student Bill Johnson, and I closed the library and then commiserated about our miserable lives until the bars closed at two o’clock. Caryl Lloyd and Jo might listen sympathetically or tell us to stop whining. The five written and oral tests had to be taken within two weeks. I began on a Wednesday, giving me a day or a weekend between each written exam and another weekend before the oral. Debriefing afterward with friends helped me discern my errors.

The conventional wisdom about oral examinations that “much is expected and little is given” aptly described my experience. We gathered at 2:30 in the department chair’s office. Stow invited me to sit at the head of a large table. “I prefer to think of it as the foot,” I quipped. “What happens here will determine that,” he responded. Senior members Mead and Aydelotte asked perfunctory questions. Rohrbough followed their lead. At some point, Stow asked: “Were Methodists Arminian?” Not knowing the answer to this theological point, I said: “Their enemies said they were.” He simply cocked an eyebrow. Newcomer Sternstein grilled me on numerous details, which Persons mercifully cut short. After little more than an hour, I felt like I was under the table. The committee asked me to leave the room, and quickly gave me a pass. Rohrbough congratulated me as the rest hurriedly departed as if all were rushing to catch a bus. Fear of failure prevented planning a celebration, so Jo and I simply shared supper and a bottle of wine with our upstairs historian neighbors, Jim Hamilton and Tom Schlereth.

I passed comprehensives on January 16, 1967 shortly before the department simplified doctoral requirements to help candidates earn degrees more quickly. The reforms abolished total credits and an outside area, reduced research seminars and examination fields from five to four, and permitted substituting statistics or some other research tool for the second foreign language when relevant to the candidate’s research. These changes made me an ABD (all-but-dissertation) at the end of the spring semester after completing the required two-credit Philosophy of History taught by Aydelotte. Although several of my fellows disdained the subject as a waste of time, I found it fascinating as a subset of intellectual history. We met weekly in two-hour sessions to discuss assigned readings and listen to guests lecturing about causation, objectivity, cyclical or Christian theories, quantification, and other subjects. I wrote a paper on the Historiography of American Public Education, which Aydelotte praised for “moving along sprightly” and criticized for “overstating the shortcomings of educational historians.” As an ABD, I had an excellent chance to complete my degree by summer 1968. Instead, unforeseen events compelled me busily to cram one year’s work into two.

Protesting the War

Radical students did not foresee how their dissent during the Sixties would weaken the power and prestige of American higher education. Crowded campuses evidenced in overflowing lecture halls, dormitories, and cafeterias as well as political consciousness stirred by the civil rights campaign, free speech movement, and Vietnam War engendered demonstrations. Protestors initially adhered to campus codes of responsibility and respect, but their commitment eroded when demanded change did not come quickly enough. Alienated activists moved progressively from rational discourse toward violent confrontation. Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and New University Conference (NUC) planned most Iowa protests. I witnessed transformation of attitudes, activities, and tactics from the movement’s fringes. I believed civic duty required a public declaration against an immoral war at the same time my desire to finish a doctorate limited my involvement.

United States escalation of the Vietnam War spawned a peace movement on university campuses first manifested on March 24, 1965 at the University of Michigan where more than 3000 collegians attended an all-night teach-in. The idea turned contagious, infecting many other universities. A crowd of 12,000 gathered to hear Dr. Spock, Alaska Senator Ernest Gruening, and other speakers during a two-day event at Berkeley. I was in a small crowd at the Iowa Library’s Shambaugh Auditorium on a Saturday afternoon when Christopher Lasch stated his opposition to United States intervention. Teach-ins made dissent respectable and the government defensive. The Johnson administration struggled to recruit reputable advocates for its policies, and the three-man ‘truth squad’ dispatched to the Midwest in May was booed at Iowa and shouted down at Wisconsin. At the same time student Stephen Smith burned his draft card on October 20, 1965 at the Iowa Memorial Union Soapbox Sound Off, Lasch reached a national audience by publishing “New Curriculum for Teach-Ins” in the Nation. Nearly one hundred witnessed Smith’s civil disobedience, including the journalists and TV cameramen he had invited. SDS, somewhat ironically given its motto “Build Not Burn,” praised Smith’s courage. Recently approved by the Student Senate as an official campus organization, SDS recruited a cadre of “peaceful activists” to raise consciousness against the war and for curriculum reform.

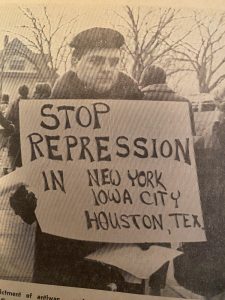

After much anxious reflection, I screwed up sufficient courage to attend the Iowa City Vietnam Day Rally on November 7. 1966. SDS, the University of Iowa Vietnam Days Committee, Iowa Socialist League, and Friends of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee planned the event as part of a national antiwar protest. About 250 protestors gathered at College Green Park at 600 E. College Street and marched to the Pentacrest behind a banner “We are Sick of the War.” Some carried signs “Peace for All” and “We Wanted a War on Poverty Not Vietnam,” sang freedom songs, and exchanged shouts with hecklers who gathered along the street and tossed eggs, water-filled balloons, and stones. Anthropology Professor Donald Barnett and twenty-eight others spoke from the steps of the Old Capitol. I had departed before a crowd of counter-demonstrators gathered to disrupt the rally. Barnett complained afterward that the police should have done more to restrain hecklers.

Comprehensive examinations in January 1967 kept me from thinking about an SDS-organized sit-in protesting CIA recruiters. At an Anti-Dow rally the next month, a student speaker charged the University of Iowa with complicity in the Vietnam War, calling it “an obliging prostitute serving interests of corporations.” Not all demonstrations were strident. The first “Gentle Thursday” on May 11 declared a day of “gentleness, love, peace, and happiness.” Flowers and peace symbols were painted on sidewalks, Volkswagens, and bodies. Candy and hallucinogens were shared. Thousands gathered on the Pentacrest listened to Allen Ginsberg perform a ten-minute Buddhist chant and read poetry. A pig roast honored him that evening at a dilapidated house History friend Craig Lloyd rented in a wooded area on the Iowa River. When Craig announced the poet’s presence, he felt Ginsberg’s hands around his neck. It seems Allen took exception to having a fuss made about his arrival. I regret not attending such an historic occasion, but the logistics of parking numerous cars on a country lane at night put me off.

A major disruption occurred November 1 when 200 students and faculty blocked the Iowa Memorial Union east entrance in theory obstructing Marine recruitment interviews. While interviewees entered elsewhere, University police watched behind locked doors as counter-demonstrators tried to force their way through the linked arms of protesters. A large crowd spilled across Madison Street into all four levels of a parking ramp and shouted red baiting slurs, obscenities, and other insults. I did not picket as planned because there was no room to set up a line. The affray ended when city police, highway patrolmen, and sheriff’s deputies equipped with helmets and clubs moved in and arrested 108 demonstrators. They did not detain or charge any in the crowd that had threatened the resisters with harm. Two days later, President Bowen announced he would take disciplinary action against the rule-breakers who prevented other students from entering the Memorial Union. As demonstrators had not obstructed any other Union entrances, Bowen’s claim seemed farcical. The president’s act precipitated a chain of events pitting ever more strident protests against Iowa City police and university administration.

The locally published underground newspaper, Middle Earth, took its name from J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy and identified with the emerging counter-culture. Alienation from liberalism as well as commitment to non-violent civil disobedience and incitement of revolution separated its chronicling of student activism from traditional reporting. In analyzing how the counter-demonstrators had behaved, writer Everett Frost (later an NPR producer and author of dramas) noted how sorority beauties had yelled sexual epithets; he concluded they suffered from sexual repression and suggested holding “a screw-in” as a cure for their condition. The university community scarcely required editorial encouragement. Many had already signed up to do their bit for the Sixties sexual revolution. Our political scientist neighbor across the hall on Dubuque Street, seemingly pleasured women two at a time on weekends. Graduate students gossiped about philandering professors whose affairs had furnished literary material for aspiring writers. Moxie, an aptly nicknamed undergraduate I knew from our days at church camp, seduced his student teaching supervisor. The pair carried on a seven-month affair without his or her spouse becoming aware. The assignation ended when graduation removed the Monday night class excuse he had given for leaving his Muscatine home. Rumors circulated about several sexually unfaithful or promiscuous student and faculty couples and singles. Many believed “What we did in the Sixties never hurt anyone,” as one of my female friends observed. Others may have been shamed by their acts upon further reflection.

A new attitude of resistance exploded in a December demonstration against Dow Chemical, a manufacturer of napalm bombs widely used by the United States in Vietnam. The company held interviews inside the Iowa Memorial Union. I joined a picket line at the south entrance on Jefferson Street as other demonstrators stood and chanted: “Stop Dow Now,” “Stop the Cops Not the People,” and “No More Napalm.” When some of the crowd entered the building, a line of black-clad, white-helmeted state police marched down Jefferson Street, bypassed the picketers, and converged on the protesters inside liberally wielding their clubs and mace. They arrested eighteen and carted them off to jail. Cellmates of English graduate student Fred McTaggart demanded that he be given medical treatment for his bleeding wound. After police dropped McTaggart at University Hospital and his head had been bandaged, he called the station and asked: “Should I return?” The desk sergeant sent another squad car to bring back for booking. I sat near McTaggart in the Graduate Student Study Area. The next day, his bandaged skull mirrored those of the white-helmeted policeman who had beaten him. The Johnson County Attorney indicted him and six other SDS members for conspiracy the following spring. Picketers gathered outside the Court House to support “the Iowa City Seven.” President Bowen called the demonstrators “irresponsible.” City Manager Frank Smiley said, “We will crack as many heads as necessary.” McTaggart avoided jail and later published his doctoral folklore dissertation as a notable book: Wolf That I Am: In Search of the Red Earth People.

I ceased taking part in antiwar demonstrations thereafter but still experienced tear-gas at Paul Goodman’s public lecture in the Iowa Memorial Union Ballroom on June 7, 1968. Lasch’s seminar on American Social Theory had introduced me to his best-known book, Growing Up Absurd. Goodman, regarded as the intellectual father of the New Left, had been brought to campus as the featured speaker at an underground press seminar. The year before, he had published a New York Review of Books essay, urging massive direct action against the draft. In supporting the Berkeley Free Speech Movement, he had labeled the American college student “the most exploited person in America.” Goodman concluded his public talk after the air had cleared. I sampled enough gas to appreciate its usefulness as a means of crowd control. Harry Edwards, the physically imposing Black activist organizer of the Olympic Boycott, spoke at a University of Iowa Student Power Symposium on January 20, 1969. Leftist historian Alan Spitzer acted as moderator. When Edwards dismissed his overly academic question as “honky bullshit,” Spitzer’s face visibly paled while maintaining his composure.

The political savvy and commitment members of the League of Women Voters displayed in the Iowa City antiwar movement drew me to the Eugene McCarthy presidential campaign. I spent a chilly March Saturday canvassing in Cedar Rapids and later attended my neighborhood precinct caucus. McCarthy supporters showed up en masse and took over the meeting while the handful of regulars who normally conducted party business glumly drank coffee in the kitchen. Unlike those who got “got clean for Gene,” I had grown a beard. Nevertheless, the caucus elected me chairman as well as a member of the McCarthy delegate slate for the Johnson County Convention. This meeting sent a mostly McCarthy delegation to the state convention in Des Moines where it did not prevail. My brief entry into politics ended with Robert Kennedy’s death and Hubert Humphrey’s nomination during a police riot in Chicago. National television coverage of the debacle facilitated Nixon’s law and order campaign and helped elect him president. Had Humphrey broken with the Johnson administration and openly opposed the Vietnam War three weeks earlier, he could have been elected president, sparing the United States from a troubled history spawned by the Nixon administration’s abuse of power.

In May 1968, SDS and NUC presented a petition to Governor Harold Hughes demanding immediate elimination of ROTC at the University of Iowa. Abolition of the program remained a driving force behind subsequent demonstrations after I left campus a year later. News that Ohio National Guardsmen had killed four students and wounded nine at Kent State University on May 4, 1970 caused escalating tensions between protesters and Iowa City police to explode when 1500 demonstrators gathered on the Pentacrest. Militants broke windows and destroyed furniture in the Old Capitol and Jessup Hall. At President Boyd’s request, police cleared the area, arresting 300 students. The Rhetoric Building next to the Old Armory mysteriously burned the next day. At a second rally and a sit-in staged to block downtown traffic, a handful threw rocks though the windows of downtown businesses and an explosion shattered storefronts on Dubuque Street. As a consequence, the president gave collegians the option to leave the university early, and many did. Stow Persons, the faculty senate president that tumultuous year, feared the campus had been permanently politicized. Yet demonstrations decayed when a majority dropped out due to drugs, divisions, and disillusionment. “Careerism” returned and quiet resumed at the school. Ronald Reagan and other conservatives challenged the low tuition policies that fueled higher postwar enrollments. The subsequent decline of state support for public higher education caused a financial pinch that has persisted ever since.

Sixties radicalism substantially altered American culture and politics. The civil rights movement expanded from freeing African-Americans to liberating women, Native Americans, Lesbians and Gays, and other disadvantaged groups. For example, women emerged from the margins of social activism and achieved feminism, women’s studies, access to graduate and professional schools, and employment in corporate, government, higher education, and medical worlds. The liberal consensus disintegrated. A conservative coalition of evangelical Christians, Sagebrush rebels, and free market Republicans challenged New Deal solutions and waged war against cultural changes brought by the liberation of previously disadvantaged groups. A new moral majority rejected sexual promiscuity and homosexual marriage and upheld the traditional family of monogamous working fathers and stay-at-home mothers. American politics polarized into hyper-partisan factions incapable of governing the nation by the 21st century. As a consequence, a befuddled angry electorate elected seriously under qualified billionaire magnate Donald Trump as president in 2016. This unlikely outcome again made best sellers of Sinclair Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here and George Orwell’s 1984.

Social and Family Life

While playing touch football with history graduate students on the Women’s Athletic Field in October 1965, I sprained my knee. Two friends took me to the Health Service, where I was evaluated and sent home on crutches. The three of us were having a cold beer when Jo returned from school. “What the hell have you done to yourself now,” she snapped and stomped into the kitchen to fix supper. Not knowing the cause of her outburst my mates departed quickly. Her hunger-fueled crabbiness was not uncommon after a day of teaching physical education to three hundred elementary pupils. Yet Jo stayed angry for the next two years, growing jealous of my mistress, Clio the goddess of history. Feeling neglected, she complained about the long hours I spent studying and demanded: “How long will it continue?” I responded: “Until I finish my degree.” Work had indeed made me dull, tired, and testy. I might have altered my schedule and spent more time at home but feared being distracted by TV or her. As our quarreling escalated, we compared ourselves to Martha, a shrewish wife, and George, her battling historian husband, who Edward Albee famously dramatized in his play, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

Although our relationship grew less embattled the next year, Jo’s unhappiness festered, and finally exploded the day after our fourth anniversary. “I don’t love you. And I don’t want to be married to you anymore,” she declared at a Minnesota farmhouse where we were staying with the family of friends. Her hard words turned my bowels to water. During an agonizingly long week camping on Madeline Island in Lake Superior with two other married couples, we feigned compatibility and wandered off by ourselves for long talks. Her grievances were many: “You work too much!” “We never do fun things!” “You don’t go to my school events!” “You are too radical!” The latter charge stemmed from my antiwar activities and ideas quoted from reading the New York Review of Books to which I had recently subscribed.

Upon returning to Iowa City, she announced: “I am moving out at the end of the school year. You can stay until then.” I looked for another place without success and resisted divorce because I did not want to start over with anyone else. Jo relented after talking with Larry Ingraham, a psychology doctoral student and a friend from SCI who now occupied the upstairs apartment with Jim. She never shared what Larry advised or what changed her mind. He likely told her what he told me: “You need to take your share of responsibility for what went wrong.” Thirty years on, while visiting one of Jo’s Iowa City teaching friends now divorced and living in Vermont, the woman said with some surprise: “You two have a lot of regard for one another.” She could not have said that about us during the early years of our marriage when love had been neither patient nor kind. At our fiftieth anniversary celebratory dinner in Hawaii with two daughters, a son-in-law, and four grandchildren, the waitress who served us told me afterward: “It is such a nice family.” A few years later on a Road Scholar tour of England, Gladys—a conservative hairdresser from near Toronto with whom we had bonded—remarked: “You two are really good together!” We all have at least three marriages in their lifetimes, researchers suggest, whether we change spouses or not. The observation rings true for us. Our life together turned out better than we could have hoped upon reconciling after so many bitter months more than a half-century ago.

ABD status lessened academic pressures on me and enabled an expanded social life, making Jo happier. We cheered the basketball team guided by hall-of-fame coach Ralph Miller and especially enjoyed watching high-scoring forward Sam Williams carry the 1967-68 Hawkeyes to a Big Ten Championship. New football coach Ray Nagel rewarded our attendance at Hawkeye games by converting QB Ed Podolak into a star running back who led the 1968 squad to five wins and just five losses, ending a string of four losing seasons. College sports had great public appeal in the Sixties, but at times polarized along the lines of campus and national politics. Southern schools desegregated athletic teams and Black athletes felt isolated on majority White campuses North and South. Black football players revolted at Iowa in 1969 and derailed the chance for a winning football record. Nagel left and the program resumed its losing ways until the coming of Hayden Fry in 1979. By then, big time sports had commercialized even more, which gave athletic departments greater autonomy within the university. Scholarships changed to one-year awards subject to renewal, and freshmen eligibility allowed them to play four years over five seasons. Coaches and Athletic Directors lavished talented athletes with perks, but subjected them to strict discipline aimed at suppressing counter-cultural behaviors and revolts rather than ensuring higher graduation rates.

In addition to sports spectating, I played touch football in the fall and basketball year-round at the Recreation Center, the Iowa Field House, the Veteran’s Hospital outdoor court, and the Roosevelt Elementary School Gym on Sunday afternoons. Our intramural team comprised of Comparative Literature, History, and Political Science graduate students battled the Hawkeye football team for the championship on the Iowa Field House main court. We lost badly after former Simpson College star Tom Hensley sprained his ankle just before halftime. We fared better that spring by beating English graduate students for the intramural fast-pitch softball championship. Several of us spent two summers on the Mean’s Agency team in the Iowa City slow-pitch softball league. We played at Happy Hollow Park on a field featuring a steep embankment in center field. Speedy Ken Wagner displayed mountain goat skill in scaling the heights and taking away hits. We even beat a team on which Hawkeye running back and future Vikings Coach Dennis Green patrolled right field. Ed Podolak, who had displaced Green and later starred for the Kansas City Chiefs, played with us the second season.

During 1965, I had started playing squash and racket ball with newcomers Russ Menard and Tom Schlereth. Both were “stars” and had lengthy teaching careers at the universities of Minnesota and Notre Dame respectively. As students, Russ kept me informed about important books. When I complimented him on his bibliographic knowledge, he claimed to have learned it all from Tom. Russ told me about Ferdinand Braudel and the French Annales School, which aimed to write history in its totality enriched by other social sciences. He urged reading Phillippe Ariès, Centuries of Childhood: A Social History of Family Life for my doctoral dissertation and I learned that children had been considered little adults until the 15th century. Hence, the concept of childhood as a separate life stage was a modern development. Russ also introduced me to E. P. Thompson, a founder of Past and Present in 1952, a journal simultaneously influenced by the Annales School to advance the study of social history. A decade later, Thompson authored The Making of the English Working Class. Marxists like him, Christopher Hill, and Eric Hobsbawm advocated the study of history from below. Hobsbawm’s accessible, wide-ranging works of synthesis made him one of the best-known historians in the English-speaking world at a time when history had become increasingly specialized.

Jo and I developed close life-long friendships with several couples. Russ and Kathy Menard frequently played bridge with us. Joan and Robert Klaus served meals featuring cuts of meat provided by his Chicago butcher father. She and Jo taught at Roosevelt Elementary School where teachers and spouses played Friday night volleyball. The side with Hawkeye basketball player Gary Olson usually won. Robert earned the moniker “bag Bob” for showing up encased in plastic to lose weight. Law student and SCI graduate Jack Kelly and his wife, Jean, entertained us with servings of smoked Coho Salmon and tales of their Alaskan adventures at their West Branch home. Jack and Jo finished painting the house while I wrote my dissertation abstract in an upstairs room before we watched the historic moon landing together that evening. We also enjoyed having meals with Craig and Caryl Lloyd and others at the large partially decayed old house they rented on the Iowa River.

I enlivened the annual Roosevelt School Christmas party by mixing an exceptionally potent fruit punch (one bottle of vodka, one bottle of white wine, ten ounces of pineapple juice, and an ice ring). The room immediately exploded into a cacophony of conversation. A few stopped drinking when they observed what the recipe contained. I even benefited from the less enjoyable physical educators spring dinner, when conversation with the Iowa department head put me on weight training to strengthen my frequently sprained knee.

Sidney and Mildred Mead fortunately included us with Tom Schlereth, Jim Hamilton, and others at a Thanksgiving dinner. The engaging, well-traveled couple had an architecturally modern home located in a hilly, wooded neighborhood. Original art works, including her pottery and photographs taken during Chicago urban renewal, decorated the interior. We reciprocated by inviting them to a New Year’s Eve Party at 323 North Lucas. “Millie” got a bit tipsy and spoke too frankly about aging and sagging breasts, which irritated him. He did not hold a grudge, and she kept us on the guest list for celebrating his 65th birthday shortly before we left Iowa City. These occasions were among our happiest during the graduate school grind. Some events were too raucous to invite the Meads or other faculty. At a memorable “purple passion party” we consumed a case of vodka mixed with Welsh’s Grape Juice. As our conversation grew loud and our dancing frenzied, Caryl walked into the back yard fence and became hung up until freed by Craig. Someone knocked out a front porch screen, alarming our elderly neighbors. Somehow soft-spoken punster-poet David Gebhardt persuaded them not to call the police. Hangovers the next day added to the psychic pain many of us felt for Robert Kennedy’s recent assassination.

A new 1967 Ford Mustang purchased to facilitate doing more “fun things” had sealed our reconciliation. When hail damaged the car six months later, we used the insurance money to buy camping equipment for a western trip. We managed quite well even though Mustangs were not designed with camping in mind. The canvas tent, cots, sleeping bags, lantern, portable grill, and charcoal overflowed the trunk and the spare tire, clothing, and other supplies filled the back seat. We pitched our tent the first night at Lake McConaughy near Ogallala, Nebraska. We then went urban, spending a few days with Tom and Ann Bruce in Denver. His extensive mountain driving enabled flatlanders like us to take in the mountain scenery. While thick fog at Rocky Mountain National Park kept us from enjoying the vista, we later fared better at the top of Pike’s Peak.

Jo and I then headed south to the mining community of Cripple Creek and west to the Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park. We later camped at Mesa Verde National Park and toured the cliff dwellings there. We then stopped in turn at the Petrified Forest, meteor crater, and the Grand Canyon. After marveling at the man-made wonder of Hoover Dam, we spent a miserably hot night at the Willow Beach campground. Arriving at Las Vegas shortly after sunrise, we saw actor Telly Savalas at the tables. His grumpy expression suggested he had not been lucky. We quickly lost our seven-dollar limit playing the nickel slot machines before driving north across Nevada’s barren wastes to Yosemite National Park. No reservations were required then, and we were fortunate to find a valley campsite. A picture of me sitting on a wall at Lookout Point, framed by the park’s scenic splendor, still adorns my study wall. From there, we reached the Pacific Ocean at Santa Cruz. After camping and visiting the university there, I fantasized about teaching in such a lovely place. My undistinguished academic record ensured University of California jobs were a pipe dream.

Iowa City friends John and Sue Sommerville put us up for a night at their home in Palo Alto, where he had taken a three-year appointment in Stanford’s Western Civilization program. SCI roommate Cecil Shaw joined us for dinner. It would be the last time we saw him, although we spoke several times by telephone before his death in 2008. The next day John gave us a tour of some San Francisco highlights: Golden Gate Bridge, Chinatown, Fisherman’s Wharf, and the hippies of Haight-Ashbury. Jo and I then crossed the Bay Bridge for my pilgrimage to the University of California-Berkeley and Telegraph Avenue. I most enjoyed the bookstores and the movie theatres featuring classic American films. We toured some Napa Valley wineries before heading east on Interstate 80. We camped at Reno and spent Saturday night in a casino where women in cotton print dresses, bourbon highball in hand, played slot machines, and we quickly lost another seven dollars in nickels. We hurried across Nevada with all windows rolled down, stopping only for gasoline and toilets until we reached Salt Lake City. There we visited the Mormon Tabernacle and other historic sites, including several ice cream parlors. After three weeks touring, we dropped plans to visit Yellowstone Park and returned home. While Jo drove, I filled the Great Plains void by reading J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, a trilogy with cult status among graduate students. It had been a wonderful trip, stimulating my desire for a job somewhere in the West after I completed my degree.

ABD – All But Dissertation

When I passed comprehensive examinations on January 16, 1967, it seemed possible to complete my doctorate in the next eighteen months. The department had approved my thesis topic and by the end of the second semester, I had written two more papers on the subject for Aydelotte, and Sternstein. The latter called “Iowa Educators and Compulsory Education, 1885-1905” a decent essay, which emphasis on the Americanization of Iowa ethnic groups would improve.” I had the additional advantage of not needing to expend time and expense in traveling to distant archives. Instead, I did most my research in Iowa City, walking just a few blocks to the State Historical Society of Iowa (SHSI) at 402 Iowa Avenue or the Education Library in East Hall (formerly the University of Iowa Hospital) situated on the next block. SHSI was the personal fiefdom of Superintendent William J. Peterson, who boosted membership from 1000 to 11,000 during his twenty-five year tenure. He persuaded Iowa legislators to build SHSI headquarters in Iowa City and raised part of the necessary $500,000. His Steamboating on the Upper Mississippi (1937), one of the finest histories of commerce on the river, gave him the moniker “Steamboat Bill.” He also was known as “Mr. Iowa History” for authoring 400 articles in the society’s magazine, Palimpsest. Unhappily, SHSI was a noisy place to work because “Mrs. Iowa History” often loudly proclaimed the library’s virtues. On her worst days, Bessie sounded like one of the obnoxious wives that tormented comedian W. C. Fields in his films.

Throughout the second semester and summer, I spent most weekdays in the archives accumulating file boxes of notes while winding down like a worn-out clock. Meanwhile, the history department adopted a three-year limit on financial aid and once more took away the TA I had held during the spring term. When Professor Lawrence Gelfand gave me the bad news, I responded: “Technically I have received just two and one-half years of aid.” He ignored my comment and ended our interview. I had already lost my way in researching, when Jo announced she wanted a divorce further darkening my mood and compelling me to take time to repair our fractured marriage. I resumed work by reviewing my notes and writing a thirty-page prospectus that I presented to Persons in January 1968. Impressed, he remarked: “The results could be quite spectacular if you can pull it off.” An unexpected dividend arrived by mail in March when a $3600 Teaching Research Fellowship dropped into my lap. How could the department make me a Teaching Research Fellow after declaring me ineligible for assistance? I credit Stow for my sudden change in fortune. Recently the department had shortened the program because too many students were not finishing or taking too long to complete their degrees. My prospectus may have persuaded Persons that I would most likely finish sooner than later.

My Iowa pattern of working hard but not smart made my thesis less successful than Stow had hoped. I expended too much time and energy advancing what I self-importantly called “my cultural self-improvement” by auditing courses and collecting lecture notes on subjects of interest to me. When I sat in on Malcolm Rohrbough’s Westward Movement in the United States, he asked: “Why are you here?” I replied: “My exams showed a need to know more about the American West.” He seemed impressed, saying: “Your willingness reveals a lot about you.” I next audited Sherman Paul’s American Criticism and Culture. The renowned literary scholar wrote and edited more than twenty books on Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Edmund Wilson, and other authors in what he called “the green American tradition.” My best auditing adventure came from Readings in Afro-American History, the first Black history course offered at Iowa. Professor Robert Dykstra and graduate student Russ Menard organized the two-semester class. I expected studying slavery and post-emancipation African-American life through reading such authors as Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, W. E. B. DuBois, Richard Wright, James Baldwin, Malcolm X, and others would improve my job prospects. Black radicals were demanding fewer courses about “dead, White males” so it seemed wise to learn African American history. Although I never seized my opportunities to teach the subject, I included African American authors and topics in my United States history survey and other courses throughout my career.

Other literature and history courses were less rewarding. For example, a professor hired to develop a new American Economic History course taught poorly and soon took a banking job. Several two-semester sets of Fybate Lecture Notes purchased from the University of California – Berkeley on the history of world and American literature, political theory, philosophy, and Modern European Intellectual History later proved useful in teaching, but it would have been wiser professionally to have focused more on writing a dissertation than pursuing such esoteric cultural interests. Although auditing education and Iowa history courses taught respectively by William Duffy and “Steamboat Bill” Peterson would have given me a deeper knowledge of Iowa schools and their social context, I arrogantly assumed neither could teach me anything useful. Bernard Bailyn had lowered my opinion of the narrow educational history taught by professors of education and academic historians dismissed Peterson as a popularizer who permitted SHSI scholarly standards to deteriorate. Instead of studying how Iowa educators, farmers, workers, businessmen, churchmen, lawyers, and politician had conceived the cultural values common schools ought to transmit as originally planned. I instead narrowed my focus to how educators viewed the common schools as an instrument for training ideal American citizens. By not framing issues more clearly and discussing them at length with Stow or Sidney Mead, I missed by opportunity to analyze educational advocacy by other groups and thereby more broadly articulate the process of cultural transmission in Iowa education.

I also wasted summer 1968 by writing an entire rough draft of chapters outlined in my prospectus without thoroughly revising each one before proceeding. A better strategy would have been to expand three papers I had already written and transform them into dissertation chapters. I did not seriously revise the rough draft until the fall term when fellow historians and housemates Jon Kolb and Joe Rosenberg went through three chapters line by line with me. They had a grand time poking fun at my awkward phrasing and word choices. It would be the only compensation they received for their invaluable help in making me write better.