7 Endings

Endings and beginnings frame every human life. The former denotes conclusion, termination, or death. It also can mean to bring or come to an end; to die or to put to death; or to be at the end of something. Here ending refers principally to the conclusion of my paid work life. It is a stage during which beginnings have occurred and may do so until I die. As a farm kid, I early encountered ending as death. At age four, I watched our collie Sport die in the front yard after being hit while chasing a car. The driver deliberately turned out to kill him. Not long after, we had another dog Shep spayed. I found her in a small shed after rigor mortis had set in. Death demands removing remains. I don’t recall what became of Sport and Shep. Farmers routinely called for the rendering truck when large animals died. It would arrive before carcasses putrefied and cart them off. For dead chickens or piglets, I would be handed a spade, sent to the cornfield, and instructed: “Dig deep and pack the dirt so an animal doesn’t dig them up.”

My parents took me at a young age to wakes and funerals. Open caskets were the rule. My earliest recollection of these occasions is viewing Oscar Meisner’s body at his farm home. He had suffered a heart attack while putting up hay. We sat near the casket so I had a good view of his frozen features and brown suit. Neighbors and friends sympathetically comforted the grieving family saying, “He looks so natural.” I wondered what “natural” meant. To me, he looked “different” from the man who had saved me from injury by reaching down and pulling my three-year-old self from beneath the grain wagon I had fallen from. To me, Oscar looked dead. His daughter Faith and I graduated together from State College of Iowa fifteen years later. We had not met since her family moved away. Neighborliness compelled Father to seek out and say hello to Faith’s mother after the ceremony.

Is There Life After Retirement?

My generation of farm kids had less experience with the notion of retirement as the end of one’s work life. Lots of farmers like Oscar retired by dying. And farm wives still cooked, cleaned, and washed clothes even if their husbands lived and moved to town. I suppose the lack of cattle, hog, and chicken excrement made their lives easier. Maternal grandparents Ruth and Adolph Olson followed a different path. She suffered a stroke and died at age sixty-five. Her wake was held at home. A meal served to the large extended family preceded the funeral at the Norway Lutheran Church. Adolph took over the cooking for their bachelor son who continued farming on a smaller place. He additionally worked several quarters at an advanced age to qualify for Social Security payments. Even then, he kept house after a fashion. Mother came periodically to clean and wash clothes. Adolph outlived Ruth by nearly twenty years.

Paternal grandparents Robert and Ella Engelhardt retired to Elkader in 1945 when their youngest son, Allan, married and took over their eighty-acre farm. Robert kept a large garden, did repairs on his own home, drove tractor for other farmers, and helped his sons on their farms. He fished the Turkey River in his free time, and shared his usual catch of bony suckers with us. Ella carried on as before: cooking, baking, cleaning, washing clothes, berry picking, getting poison ivy, canning, quilting, and crocheting. She had no discernible free time. Breast cancer killed her at age seventy-three; her husband predeceased her at age seventy-one, dying from a heart attack just four years before.

Parents Curtis and Ruby Engelhardt sold their farm and moved to Elkader in 1974. Father was almost sixty-three and Mother nearly sixty-one. Both had worked hard their entire lives. They did not want me to forget my rural origins. Father presented me with the milk stool that he made when I started milking cows by hand at age eleven. Mother later gave me a small rubber cow she had received as a favor at the Luana Bank Dairy Days Celebration. She also saved the restored and brightly repainted red wooden tractor that Father had made for me as a Christmas gift during the Second World War when metal toys were not available. I still sit on the stool when sharpening my lawn mower blade with Father’s whetstone or picking pine needles from the decorative rocks around the foundation of our house. These tasks are not as hard as putting one’s head into the flank of a Guernsey at six o’clock in the morning. The cow stands on my desk and the tractor is parked on the sun porch as reminders of rural boyhood days I recounted in The Farm at Holstein Dip.

Father’s retirement lasted less than five years. His premature death at age sixty-seven persuaded me to retire early. He happily kept himself occupied as the town handyman well-qualified by his mechanical bent. He cut hedges, mowed lawns, and fixed doors, windows, furniture, fences, clocks, appliances, or anything else someone brought him. He died after surgery for previously undetected bile duct cancer. It had advanced too far for treatment by removal, chemotherapy, or radiation. He was left with a large tumor and a nasty looking, lengthy abdominal incision. The surgeons hoped he would recover sufficiently to return home. They were wrong. Mother and I were at his bedside two weeks later when he sighed profoundly and passed away.

Mother lived in her home an additional eighteen years. She kept house, hired out the lawn mowing and snow shoveling, and relied on neighbors for rides to medical appointments, grocery shopping, and church. She enjoyed my family’s thrice-annual visits, Bible study, and dinner dates with a widower she had known for decades. Her life became lonelier after he died. She lived long enough for her granddaughters to graduate from St. Olaf College. Yet terminal gall bladder cancer prevented her from attending Kristen’s wedding, a bitter disappointment. Kristen showed her the pictures shortly before her death at age eighty-three. She had spent ten weeks in the Elkader Hospital after surgery had revealed her malignancy. Her pastor, brother Don, Jo, and I were at her bedside when she passed. We were thankful the hospital let her stay so long and to hospice for assisting with her care. She feared being sentenced to the local nursing home where her brother had lived nearly fifteen years before dying.

Were my parents’ endings a rehearsal for my own? Mother had sat with her mother and husband as they died. She expected the same from me. I am glad to have honored her wish. My parents were not given to displays of affection or professions of love. They did not talk about their impending deaths or issue any final directives for us to carry out. Should I have initiated such a discussion? Mother’s lengthy hospitalization offered ample opportunity. Father had only thirteen days between diagnosis and death, which did not leave any of us time to sort out our feelings or act on them. Lifetimes of stoic reticence likely made such conversations impossible for them or for my brother and me who were very much our parents’ children.

Father and Grandpa Engelhardt did well in retirement. Both found meaningful tasks to occupy their time. Father often signed woodworking projects, suggesting he wanted to be remembered for pieces he left behind. I have passed some to my children and hope they eventually will do the same with my grandchildren. Brother Don did not fare as well. Arthritic hips limited his physical activity. He had no hobbies to fill his days. Fortunately, he read books by the bagful bought at a nearby Half-Price Bookstore. Overmedicated with anti-depressants and other drugs by a careless doctor, his life-long beer drinking habit spun out of control. His wife asked me to intervene, which I did clumsily without effect. After months of downing a case of beer daily, “brain bleeding” hospitalized him. He hated the many weeks spent recovering at an extended care center. When at last liberated, Don wanted to buy beer. His wife replied, “Fine, but I’m leaving as soon as we get home!” He said, “Oh” and never drank again. Too bad she did not similarly terminate his two-pack-a-day smoking habit. Don had stopped smoking and already undergone nicotine withdrawal while hospitalized. He previously quit for ten years after our cigar-smoking father died of cancer that may have started in his lung and metastasized in the liver. Don resumed the habit during the decade he worked as a nighttime prison guard.

Diagnosed with emphysema, Don fatalistically declared: “We all have to pay for our sins.” He continued puffing away even when put on oxygen—a horrific accident waiting to happen in my mind. Yet he expired peacefully at age seventy-five from COPD. As a non-church-going man, Don’s non-traditional service at Cedar Memorial Chapel featured memorable musical selections: “Your Cheating Heart” and “There is No Beer in Heaven (That’s Why We Drink it Here).” His closest friend from high school died unexpectedly one week later.

The process of thinking about how to end my work life began when I started teaching at Concordia College as a relatively young man of twenty-nine. Orientation included information about the TIAA-CREF retirement plan. President Joseph Knutson strongly encouraged our enrollment. The college and employees made matching 5 percent contributions. I took Prexy Joe’s advice, and even maximized payments during the decade before our daughters went to college. The large amount accumulated from my relatively small premiums seems miraculous. Besides taking care to save, I observed and talked with many retirees. The happiest had “reasons to get up in the morning.” They pursued many interests and believed having the choice of doing something made it less burdensome. My informal surveys helped me answer basic questions: When should I retire? How would I fill my days? Should I look for other work? Could I afford to travel? Should I relocate to Arizona like many Minnesotans do?

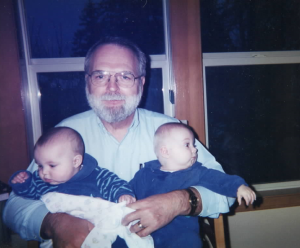

The prospect of retiring early appealed because Father and his father had quit farming at ages of sixty-two and fifty-eight respectively. After thirty-four years professing and serving on countless committees, I had tired of the grind. Pleasures of liberation made an income reduced by 50 percent acceptable. Jo kept working as a college secretary. I began drawing Social Security, took “interest only” from my TIAA annuity, and left the CREF account untouched so it continued growing. The chair unexpectedly offered me an adjunct professor position. One term teaching two courses for $11,000 proved too much work so I settled on one course at $5500 for the next seven semesters. “Merely teaching” proved pleasant. Iowa-bred rural frugality enabled our living on less money. Required Minimum Distributions at age seventy gradually pushed our income above what we had made when working fulltime. As an octogenarian, I do not regret my decision. It was good to be gone! Retirement years have passed much too quickly. New activities filled my days and kept boredom at bay. I finished old research projects and started new ones. Free time gave me more chances for community service than I had done while working. We had many enjoyable times with two sets of fraternal boy-girl grand twins as they grew from babies into teen-agers.

After a lifetime purchasing books, I finally finished all those left unread, averaging more than one hundred annually between 2004 and 2009. Rowland Berthoff’s An Unsettled People and Norman Ware’s The Labor Movement in the United States aided a book-writing project. World historian Arnold Toynbee’s A Study of History (abridged) and Americanists Charles and Mary Beard’s “progressive” The Rise of American Civilization appealed to old historiographical interests. I read Daniel Boorstin’s The Image for the pleasure of his style. C. C. Goen’s Revivalism and Separatism in New England, David Brion Davis’s Homicide in American Fiction, and William Jordy’s Henry Adams: Scientific Historian were left over from my American Intellectual History comprehensive examination reading list. I purchased Ronald Steel’s Walter Lippmann for a doing a book project left unwritten. Having at last read my professional library, I liquidated it and sold the shelves Sammy the Cabinetmaker had custom-built to hold them all. Colleagues took what they wanted. Concordia Ylvisaker Library accepted four hundred recent, unmarked volumes. I donated two hundred novels to the First Congregational Church book sale for the homeless. Hundreds of well-marked, outdated inexpensive paperbacks brought less than $50 from used bookstores. Claims that sentences marked by a discerning reader enhanced value brought eye rolling and no money. The thought of thankful heirs turned me to tossing teaching materials stored in four, four-drawer file cabinets, recycling paper, paper clips, folders, and vhs taped recordings. Sadly, my large collection of overheads had to be thrown in the trash.

Just as I had relied on the Elkader Public Library during boyhood, I often borrow books from the Concordia College library. I occasionally purchase new histories at the local Barnes and Noble or online from Amazon. When read, they are donated to the Ylvisaker Library. Jo, who scoffed at my bookish habits while working, has had a change of heart due to a lifetime spent in bad company. Yet she prefers buying to borrowing, which is surprising given her tight-fisted ways. The serendipity method of choosing volumes from the bargain shelves at Half Price Books has given me the joy of several books I otherwise would not have read: Jared Diamond’s Collapse, Derek Wilson’s Charlemagne, Ronald Spector’s Eagle Against the Sun, and Mary Renault’s The Mask of Apollo. The DVD rack has similarly given us movies like Cold Mountain or British television mystery series like A Touch of Frost. Everything is passed on to Jo’s brother in Iowa. He donates it to the Stuart Public Library collection or fund-raising sale.

Happy retirees often pursue new, more interesting ventures. In my case (as recounted in Chapter Five), I wrote five books, five articles, and seven reviews. As college historian, I continued orienting new faculty and staff for many years with talks about the institution’s past. While happy to have more time for researching and writing, I did not want to spend every day in the archives or at a PC. I also wanted to see and talk to people. While Concordia expected faculty to perform community service, my previous involvement had been limited to board membership and a few talks at First Congregational United Church of Christ Moorhead. In the decades since we joined in 1972, both the congregation and denomination have suffered shrinking membership like other mainline churches. Yet we stick because First Church is “an open and affirming congregation” with many gay, lesbian, and trans-gender members actively engaged in running the place. The love shared at Sunday worship and fellowship as well as committee meetings has blessed our lives. Preserving a progressive Christian voice in today’s fractious American society seems worthwhile to us.

With more free time and a desire to serve, I accepted the pastor’s invitation to chair a long range planning committee. A remarkably gifted preacher, Shawnthea Monroe-Mueller had boosted average Sunday attendance and wanted a remodeled sanctuary to showcase her talents. The committee gathered data on membership potential and physical plant capacity, but did not recommend expanding the sanctuary in our report to the council and congregation. We stressed that the governing boards must decide whether or not to expand the building based on the evidence we had gathered. Not getting what she wanted, the pastor left for a much larger and wealthier Shaker Heights church in Cleveland, or “Edina East” (a rich Minneapolis suburb), as one member quipped.

Subsequent service on the Pastoral Search Committee proved more rewarding. We called Mark Pettis, an excellent second career minister who had been a community organizer. Although we were his first congregation, Mark fulfilled our expectations from the start. Sadly, he stayed less than four years. He met and married a woman who served as an Associate Pastor for the southern part of the UCC Minnesota Conference. When the Conference Pastor insisted that Elena must work from state headquarters, the couple realized they could not fulfill their career goals while living in Moorhead. They accepted calls from two closely situated churches in their home state of California. Our congregation hated to see them leave, but affirmed their decision in the belief married two-career couples ought to live together if possible. Their departure created a lot of spiritual and financial turmoil caused in part by an interim pastor who was “snakebite mean” to Jo. I advised her to resign as Office Manager, but she stubbornly refused, arguing the new pastor would need her when finally called. And when Pastor Michelle Webber arrived she appreciated being welcomed by an experienced secretary.

I continued as Clerk with responsibility for taking minutes at all monthly council and annual or other business-related congregational meetings. The Clerk should also keep church records and prepare annual reports. Fortunately for me, office managers have assumed these tasks. I enjoy attending Bible Study because the sessions allow me to express my love for the scripture’s skeptical wisdom. Pre-COVID, Jo and I volunteered at the FM Food Pantry and Ruby’s Pantry, another food distribution agency that our members staffed monthly. We try to “give until it feels good.” As membership and attendance declined some disgruntled members blamed Pastor Michelle and called for her resignation. The Council and two subcommittees discussed the allegations and voted to retain the pastor. She had done an excellent job of holding the congregation together with ZOOM meetings when the COVID pandemic closed First Church for eighteen months. It is remarkable that a Christian community can survive without face-to-face contact that long. At this writing, membership and attendance seem to have stabilized. The most faithful members exhibit a can-do spirit. New budgeting processes and better office management yielded a nearly balanced 2024 budget even though recent malcontents departed, and those previously aggrieved did not come back. When I stepped aside as Church Clerk after serving fourteen years, the congregation honored me with a framed certificate of appreciation and designated January 28, 2024 Carroll Engelhardt Day.

After previously collecting United Way contributions from Concordia history faculty for twenty-six years, I resumed work as an emeriti bagman from 2008 until 2019. At that time, Concordia presidential “fixer” Tracy Moorhead recruited me for the Moorhead cemetery board. The Prairie Home Cemetery—located across Eighth Street from campus—gave Garrison Keillor the name for his radio show—“The Prairie Home Companion.” We managed the million dollar perpetual care fund for three cemeteries at quarterly breakfast meetings held at the Moorhead Fryn’ Pan Restaurant until COVID-19 relegated us to ZOOM. One fulltime employee keeps the grounds and handles sales. He is better at the former than the latter. Ghoulish humor helps us cope with his misadventures and other calamities.

FM Communiversity Board membership between 2011 and 2015 gave me a lot more pleasure. Sadly, financially challenged Concordia ended the previously self-sustaining adult education program after giving it a decent burial at a 50th Anniversary Celebration. Before Communiversity died, I put my pedagogical skills and local historical knowledge to use by teaching three well-attended courses on the early history of Fargo and Moorhead. A fourth, “American Lives, Values, and Culture” attracted twenty people and brought an invitation from the Fargo Unitarian and Universalist Society to speak about Margaret Fuller and Jane Addams at their Sunday morning worship. Sadly, no one from the mostly Caucasian Fargo-Moorhead population signed up for “Black Leaders and Black Liberation: What Can History Teach?” I had earlier talked about the topic to USDA Biosciences Research Laboratory staff at NDSU for Black History Month. I happily realized a return on my course preparation by presenting the subject as an adult education series at the First Congregational Church, which departing Pastor Mark Pettis praised highly.

I had given an occasional sermon and talks about congregationalism at Barnesville, Detroit Lakes, and Moorhead churches during the Seventies. After the mid-Eighties, I spoke about my Concordia centennial history research to various community organizations, including National Association of County Agents, Moorhead Rotary, Red River Valley Heritage Society, Trinity Lutheran Church, Fergus Falls Senior Citizens, High School Guidance Counselors, and numerous Concordia groups. My research on Fargo and Moorhead and the post-retirement publication of Gateway to the Northern Plains brought talks at the Cass and Clay County Historical Societies, Moorhead Jaycees and Kiwanis, and National Great Northern Railway Historical Society. North Dakota Public Radio and Prairie Public Television interview me at length. A Fargo Forum panel discussion featured me on its front page, and a NDSU public history class featured me in its documentary, “Prostitution and Fargo’s Most Notable Madam.” The Farm at Holstein Dip, a book about rural Iowa, afforded fewer local opportunities. I spoke and signed books at the Elkader Public Library, the Dyersville Public Library, and a McGregor variety store. I talked at Dyersville again the next year, nine Lake Agassiz Regional Libraries, and the St. James Women’s Guild in Barnesville, where members shared wonderful stories about choring and driving tractors. Recently, I spoke about my latest book By the Sweat of His Brow: The R. M. Probstfield Family at Oakport Farm at Zandbroz Variety, the Hjemkomst History and Cultural Center, three nursing homes, the Norman County Historical Society, the Hillsborough Women’s Club, the Sons of Norway, the Concordia College Emeriti, and Retired Cass County Educators. Whenever Schooling: A College Life is published I have no expectation that anyone will gather to hear what I might have to say about it.

Retirement Travels and After

Jo and I enrolled in seven weeklong Elderhostel adventures at North American locales between 2003 and 2011. We had become devoted Road Scholars, which is how Elderhostel markets its offerings, when I presented an on-campus course, “Current Revolutions in El Salvador and Nicaragua,” as well as six sessions about “American Lives, Values, and Culture” at Camp Koinonia in the southeast corner of New York state. Like Concordia May Seminars, Elderhostel minimizes stress by arranging transportation, hotels, meals, and venues. Pleasant, well-informed people coordinate daily activities, and teach. Road Scholars are affable, smart, curious, well-traveled readers, come from all walks of life, and politely discipline the chronically late.

We chose Vancouver, British Columbia, as our first destination after friends highly recommended the city. It afforded a special occasion for celebrating my retirement and our 40th wedding anniversary. It was near Eugene, Oregon, where daughter Kristen expected the birth of our first grandchildren. We headed northwest to Brandon, Manitoba via the International Peace Garden and followed the Trans-Canada Highway across Saskatchewan to Calgary, Alberta. Spectacular Canadian Rocky Mountain scenery at Banff and Lake Louise highlighted the drive to Kamloops, British Columbia, a former fur trading post and popular tourist spot where we learned Kristen had been hospitalized for bed rest. As doctors wanted to delay delivery until the thirty-fourth week, we continued as planned to Vancouver and checked into our centrally located hotel near the Pacific Ocean. We enjoyed morning walks along English Bay to the edge of Stanley Park for the next five days. On a Sunday afternoon stroll downtown, we encountered crowded streets, shops, squares, and green spaces. At dinner that evening, we met the coordinator and eighteen Road Scholars who hailed from Arizona, California, Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, Minnesota, North Carolina, and Virginia.

The Maritime Museum informed us how the seaport and export trade had boosted growth. The densely populated city ranked among the top five worldwide for livability and quality of life. Planners rejected putting a four-lane highway downtown and encouraged high-rise residential towers with protected sight lines and green spaces. The Vancouver Art Gallery occupied a former neoclassical courthouse built in 1906. The Vancouver Library Square colonnaded façade evoked the Roman Coliseum. The tent-frame Canada Place (the former Canada World Exposition Pavilion) incorporated part of the Convention Center, the Pan-Pacific Hotel, and a cruise ship terminal. Gastown and its large Steam Clock also attracts tourists. Logging and the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) drove economic growth, causing Gastown to be renamed Vancouver and incorporated as a city in 1886. Commercial buildings soon were the tallest in the British Empire.

Canada’s largest Chinatown featured a Classical Chinese Garden. The Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia had a notable collection of First Nation artifacts. Ecological planning and environmental urban sustainability created a National Wildlife Area with biking and hiking trails close to the city. In contrast, Europeans had originally cleared the largest old growth from Stanley Park by the 1890s. It is now one of the largest urban parks in North America covering one thousand acres. We abandoned plans to stay overnight in Seattle and left the program early on Friday to reach Eugene before Kristen’s cesarean delivery of twins on Saturday morning. The heavy traffic on Interstate 5 often bottlenecked behind campers and large trucks passing each other. Traffic congestion on multiple layers of exchanges at the Portland Columbia River crossing generated noxious gasoline and diesel fumes.

At birth, Cecilia and Gus Gerlach weighed almost five pounds, a respectable number for premature twins. They stayed nearly two weeks in the Natal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), and we enjoyed several fine outdoor meals at downtown cafes until the twins passed their tests for going home: taking a six-ounce feeding, sitting upright in a car seat, and registering 98.6 degrees. The Yellow Labradors carefully sniffed each small bundle. Thereafter female India lay maternally in the nursery while the babies slept and male Darby grew more neurotic as a lesser member of the pack. We stayed just over a month in Eugene, a lovely university town claiming to be “A Great City for the Arts and Outdoors.” We took long morning walks with the dogs and watched the sun set from the deck each evening. On weekends, we went to the Alton River Park where the dogs ran free and romped in the water, or once drove fifty miles to Florence, and walked the Oregon coastal beaches. The appealing Mediterranean climate started us checking the cost of houses. An additional $100,000 replicated our Moorhead amenities. Our thoughts of relocating ended when damp, Pacific Northwest winters drove the Gerlachs back to Minneapolis the next year. Having our grand twins within four hours driving time eased our regret at not moving west.

Our mid-August return to Minnesota, followed Interstate 5 north to Portland, Interstate 84 east along the Columbia River to Kennewick, Washington, and Interstate 90 northeast across the wheat-growing plateau to Spokane where we enjoyed a lovely evening at the crowed Riverfront Park and a great Mexican meal in a remodeled waterfront mill. At Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, Highway 2 took us into northwestern Montana. Dense smoke from fires made the eighty-mile drive through the Flathead Basin claustrophobic. The smoke lifted east of Marias Pass enabling an enjoyable three-day visit with Rachel at East Glacier Park Village.

Our return to Eugene the next July by way of East Glacier included a Signature City Elderhostel program at beautiful Victoria, British Columbia, on Vancouver Island. The city is named for Queen Victoria. Her statue near the majestic Empress Hotel faces the harbor where we arrived on the ferry from Port Angeles, Washington. Highlights included tours of the Parliament buildings, spacious Butchart Gardens, and a park reclaimed from a badly polluted lumber mill site that showcased Victoria’s environmental sustainability. Northwest indigenous peoples inspired Canadian artist and writer Emily Carr, who was among the first to adopt modernist and post-impressionist styles. Another local artist gave us a studio tour and told tales about living on an isolated sheep ranch. Since neither she nor her husband knew anything about rural life, their misadventures entertained the entire neighborhood. Best of all, we reconnected with Barb Bennett who had babysat newborn Kristen at Concordia. She and her second husband treated us to dinner at a lovely restaurant overlooking Puget Sound.

We returned to Minnesota from Eugene by way of Breckinridge and Dillon, Colorado, to attend a friend’s wedding. Traveling east on Interstate 84, we passed through La Grande, home to Eastern Oregon College, which had invited me to apply during my job searching days. Seeing the small city and sparsely populated forested landscape, Jo was glad I had not followed through. Moorhead had been close enough to the end of the earth for her. At Breckenridge, we shared a vacation rental apartment with Concordia friends Bob and Dorothy Homann. We walked about the former gold mining town, kibitzed at summer music festival rehearsals, and attended the rehearsal dinner. The wedding ceremony, dinner, and dance were held the next evening at nearby Dillon. On our way home, we dined with college friends Jack and Judy Moyer and their grown children at Omaha. It had been forty years since we had been together. Jack, a Vietnam veteran battling cancer likely caused by Agent Orange, looked good. We had a fine time despite differing about how Bush people had swift-boated John Kerry. The next morning, we stopped in Sioux City for coffee with our Iowa City housemate Jim Hamilton and his wife Paula.

“Pathways Through the Peaks,” an August 2007 program based at a Catholic Retreat Center in Calgary, Alberta, prompted us to arrive early for visits to the Glenbow Museum and Devonian Gardens. The former displayed Emily Carr’s art and artifacts documenting the lives of western Canadian settlers and indigenous peoples. The gardens on the Core Shopping Center fourth floor offer one of the world’s largest urban indoor botanical displays. While visiting a Prince’s Island Park exhibition, Canadians applauded us for taking an interest in their national history. Twenty-two Road Scholars hailed from the Midwest (13), South (6), and West (3). Our young coordinator turned out to be the most abrasive we have ever had. Psychotic bus driver Charley banned using the toilet he did not want to clean. Bladder-challenged septuagenarians could not always obey his command. During a rain shower, he slammed the door in my face and drove off “to clear the traffic lane,” he claimed later. Our course of study focused on regional development from the fur trade to tourism. The western most post at the Rocky Mountain House Historic Site on the confluence of the Clearwater and the North Saskatchewan rivers traded with the Blackfeet, Piegans, and the Kootenays. The elegant Fairmont Chateau overlooks turquoise, glacier-fed Lake Louise. Nearby Banff and its hot springs, was founded in the 1880s as the rail station and service center for National Park tourists. We went home by way of Glacier Park for our annual Rachel visit, driving through a burned-over area near St. Mary.

The next summer, “Albuquerque and Santa Fe” numbered just nine people. Being the lone rooster did not cause problems. “You listen,” Californian Lois said approvingly. I certainly paid her close attention. She had a tongue sharp enough to fillet fish. Three Pennsylvanian friends had traveled the world. “Rich bitch” Jean paid for their limousine airport transfers and other amenities. She objected that classes interfered with her shopping and sleeping. Group leader Gary, an award-winning artist, told her she must attend or leave. Jean called him a “lousy painter” and treated him contemptuously thereafter. Her pals were friendlier. Anthropologist Carol had many insightful comments. Ditzy Dorothy proved similarly smart if one listened closely. The course featured lectures about history, literature, art, and music; an evening movie Milagro Beanfield War and documentary Mystery of Chaco Canyon; field trips to the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center and Old Town in Albuquerque; and bus ride to Santa Fe through stunning scenery under a deep blue sky. At the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, a retired veterinarian turned docent talked informatively about her and photographer Ansel Adams. Light and landscape drew them to New Mexico. We toured downtown art galleries, the Museum of Fine Arts, and the Palace of the Governors Museum, the Chimayo and Santa Clara Pueblo, and the Petroglyph National Monument on our drive back to Albuquerque.

An Elderhostel studying Savannah, a seaport dating from the eighteenth century, enrolled eighteen. James Oglethorpe had laid out the city in eight-block wards around four squares. The Historic Savannah Foundation made it one of the largest historic districts in 1963 with twenty-one surviving squares holding monuments, statues, markers, and stately Oaks covered with Spanish moss. The Ships of the Sea Maritime Museum unfolded Savannah’s 18th and 19th century seafaring history. The Kim Polote Trio played Johnny Mercer songs at the historic Trinity Methodist Church. She even picked me to strut down the aisle with her more or less in time to the music. White Methodist founders surely would have damned such inter-racial cavorting in their House of God. Outstanding cuisine consumed at several notable eateries highlighted the program. At Mrs. Wilkes, we memorably dined family style at large tables seating ten people. The menu featured every imaginable southern artery-clogging dish. The options among three meats, twelve sides, and two desserts might comprise: fried chicken and corn bread stuffing, sausage, beef stew, meat loaf, sweet potato soufflé, candied yams, mashed potatoes, baked beans, rice with gravy, macaroni and cheese, black-eyed peas, cabbage, cole slaw, snap peas, pickled beets, okra gumbo, corn muffins, biscuits, and banana pudding. I loved every caloric-packed mouthful and considered it the quintessential Southern culinary experience.

Work demands and stock market losses limited us to Midwest trips in 2010 and 2011. The Door County Experience at the rustic Rawley’s Bay Resort beside Lake Michigan on a peninsula near Green Bay numbered thirty participants from twelve states. Sharon of New Mexico looked and talked like Jean Kelly, an Iowa City friend. Mickey of California grew up Jewish in West Union, Iowa, near my hometown during the Great Depression. “Watercolor Journals,” a lecture and workshop, invited us to express life experiences with paint. After watching a fish boil and eating the disappointing bony result, gifted Mike Orthober explained “The Surprising Art of Taxidermy.” A morning lecture “Natural History of Door County” prepared us to visit Fossil Beach, walk through the woods to Ellison Bluff, and see the Eagle Bluff Lighthouse built in 1868 of cream city brick brought to the site by boat from Detroit and Milwaukee. A naturalist talked about how glaciers created Door County Boreal Forests, and their mammal and bird inhabitants. During the free afternoon, Jo and I saw the spacious Linden Gallery housed in the landmark Prairie style former Lutheran Church in Ellison. It exhibited leading Asian artists, antiquities, and art objects. On the last day, the group toured Seaquist Orchards and its 653 acres of trees that annually produce 8.2 million pounds of Cherries. An evening concert by the Peninsula Chamber Singers ended the program.

“Architectural Gems” at the Covenant Harbor Retreat Center in southeastern Wisconsin attracted twenty-six participants from eleven states. The Evangelical Covenant Church gave us comfortable and spacious rooms, an abundance of good food at buffet meals, and excellent evening entertainment in a smoke and alcohol free environment. A twenty-minute walk along the lake path reunited drinkers with alcohol in the town of Lake Geneva and a boat tour revealed Gilded Age mansions built by the Wrigley’s and other wealthy Chicago families lining the lakeshore. The first day’s tour took us to the recently restored Wisconsin State Capitol rotunda and Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin, the architect’s ideas laboratory and a forty-eight-year work in progress. Many fireplaces underscore how hearth and home were important for Wright. Reading T. C. Boyle’s The Women alerted me to kitchen inadequacies, making it hard for Wright’s wives to entertain the great man’s many guests. Day two at the Milwaukee Art Museum showed us the first Santiago Calatrava-designed building in the United States. It features a ninety-foot high, glass walled hall enclosed by the Burke Brise Soleil, a sunscreen that opens and closes to create a unique moving sculpture. A docent guided us through Ten Chimneys, home of famous Broadway actors Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne, on day three. The actors’ historic significance and the house’s distinctive decoration made it a National Historic Landmark. The pair entertained Noël Coward, Helen Hayes, Vivian Leigh, Laurence Olivier, and others. Carol Channing once quipped, “If you go to Ten Chimneys you must have done something right.”

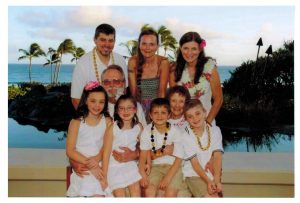

Jo and I began traveling overseas after the stock market recovery and Required Minimum Distributions at age seventy yielded additional ready cash for more expensive trips. Daughter Kristen said the family should celebrate our 50th wedding anniversary in Hawaii during her husband’s 2013 oral surgeon convention. “Capital idea,” we responded; a February trip had more appeal than going on our actual August wedding date. Rachel joined us from Montana. We spent nine days at Grand Hyatt Resort near Po’ipū Beach on the South Shore of Kauai. Daily mid-seventies temperatures, humidity-lowering trade winds, and no rain made it paradise. Adults took long morning walks or runs while roosters crowed and Jo babysat the kids. Outrageously high resort food prices encouraged economizing with Costco-bought cereal, fruit, and bread for breakfast and lunch. Adults and the six- and nine-year-old twins happily swam daily at the resort water park, which had hot tubs, slide, lazy river, and salt water and other pools. Todd joined us after attending morning sessions. At a nearby beach, we saw a beached walrus and giant sea turtle. We also drove west to the Waimea Canyon and to the North Shore. On a day trip to Honolulu and Pearl Harbor, we saw the USS Bowfin Submarine Museum and Park, USS Arizona Memorial, USS Missouri Memorial, and Pacific Aviation Museum. We learned a lot about Hawaiian-based TV shows and movies on a guided tour of the city by van, which ended with a stop at Waikiki Beach.

Hawaii prompted other February getaways. In 2015, Jo and I arrived three days early in Old San Juan for a weeklong Road Scholar program on Puerto Rican history and heritage. From our waterfront Sheraton Hotel, we walked narrow, blue cobblestone streets lined with colonial architecture. Street art decorated brightly hued, flat-roofed, brick, stone, and stucco-covered buildings. Tree-shaded squares afforded relief from tropical heat and humidity. Famed explorer and first settlement founder Ponce de Leon built La Case Blanca, home of his descendants until the mid-18th century. The Cathedral of St. John the Baptist, the oldest United States cathedral, holds his tomb. Paseo La Princesa, a broad promenade, extends from the docks to the Raíces Fountain. From there a walkway borders beautiful San Juan Bay, hugging the city wall’s base rising to a height of forty-two feet. It continues past the San Juan Gate to the harbor entrance where El Morro towers on the bluff above. The cannons and ramparts of this fortress and the Castillo de San Cristobal guarded Spain’s New World Empire for centuries.

At the renovated Museum of Art in the southern port city of Ponce, our group had a docent-guided tour of the most important European art collection in Latin America. The History of Ponce Museum documented culture, economy, politics, and daily life. The Museum of Puerto Rican Music traced the island’s musical history through Indian, Spanish and African instruments. The Tibes Indian Ceremonial Center archeological site highlighted artifacts and structures dating from 600 A.D. The Serralles family, owners of the world famous Don Q Puerto Rican Rum Distillery, built a four-story mansion overlooking Ponce. Now a museum, Castillo Serralles details the family’s socio-economic impact on the island and the history of sugar cane and rum production. The Serralles opulent elite life style was far removed from peons who harvested sugar cane, worked in sugar mills, and toiled as servants. Upon returning to San Juan, we had a docent-guided tour at the Art Museum of Puerto Rico. At the island’s east end, we hiked in the El Yunque tropical rain forest and explored a 19th century lighthouse on the northeastern headland. The preserve contained many endangered species as well as such ecological systems as dry forest, coral reefs, beaches, lagoons, and mangroves. Puerto Rico would like to develop eco-tourism on the scale of Costa Rica. It has a long way to go.

That summer, Jo and I joined the Concordia Alumni Office ten-day Norway trip. Thirty-eight well-seasoned congenial travelers started the tour in Bergen, bussed north to Trondheim, and then headed south through Lillehammer to Oslo. It was thrilling to visit the homeland of my Lerkerud (Olson), Wold, and Hulverson ancestors. Seeing Norway’s small farmsteads, fjords, forests, and snow-capped peaks helped me understand why they left and how it may have broken their hearts. It was fun to travel with Paul Rye, one of my very capable early students. Jo and I particularly enjoyed “The Bev & Mary Show,” first year Concordia roommates who lived as neighbors thirty years later. Bergen, known for its rain, bathed us with sun during our three-day stay. Brightly painted 14th century warehouses of Hanseatic League merchants near the marina document Bergen’s rich trading history. At nearby Troldhaugen, Edvard Grieg, Norway’s most famous composer composed many of his best-known works in a garden hut on “Troll Hill” by the shores of Lake Nordås. Our bus took us northward through many long tunnels, put us on ferries crossing scenic fjords, and took us down Trollstiegen (Troll’s Path) switchbacks until we reached Trondheim founded by Viking King Olav in 997. Nidaros Cathedral, erected on his grave, has been rebuilt many times usually in the Gothic style. Norwegian kings have been crowned here since the Middle Ages, when the city served as Norway’s first capital and a pilgrimage site for Christians from Northern Europe.

Oslo’s compact center enabled walking from City Hall to Akershus Castle, Opera House, National Theatre, National Gallery, Royal Palace, and numerous churches. During World War II, the German army made the castle its headquarters. Today the grounds have a Norwegian Resistance Museum. The striking Modernist Opera House is situated at the head of Oslo Fjord. Its exterior, covered with Carrara Marble and white granite, appears to rise from the water. The sloped roof forms a large plaza, where pedestrians have panoramic Oslo views. The Viking Ship Museum displayed three vessels dating to 800 A.D. found when excavating nearby tombs. The Kon-Tiki Museum celebrates famed 20th century Norwegian explorer, Thor Heyerdahl, who demonstrated how trans-oceanic travel to and from the Americas had been possible for ancient peoples. Gustave Vigeland (1869-1943) created a sculpture garden at Frogner Park. Many of the more than two hundred bronze, granite, and wrought-iron sculptures depict the stages of life from birth to death and one generation to the next. Holmenkollbaken, the ski-jumping hill that hosted the 1952 Winter Olympics, marks the city skyline. Holmenkollbaken Park Hotel gave us striking views of the city and fjord at sunset.

“A Toast to the Best of San Diego,” a February 2016 Road Scholar program featured local wines and cuisine, underscoring the city’s reliance on tourism. We arrived early so we could visit the USS Midway Aircraft Carrier and Museum as well as the adjacent small park with statues of comedian Bob Hope entertaining the troops and Unconditional Surrender, an iconic statue of a sailor kissing a nurse upon hearing that Japan’s surrender had ended the Second World War. The new domed nine-story San Diego Central Public Library had a large lobby and open floor plan, and an open deck for viewing the city, and the latest technology. Despite patrons’ complaints, the staff meets the needs of the nearby homeless camp as best it can. At Balboa Park, the Air and Space Museum treated us to a Leonardo da Vinci exhibition and galleries displaying aircraft from the First and Second World Wars. Our group of thirty-seven came from thirteen states. We learned that military bases and defense industries stimulated the city’s growth during and after World War II. San Diego is still home to the United States Pacific Fleet, a fact confirmed by a two-hour cruise of San Diego Bay. A guided walk of Little Italy demonstrated how tourism had kept it alive after San Diego ceased being “the world’s Tuna capital” in the Eighties, The Chicano Park Murals revealed a neighborhood displaced by Bay Bridge construction. Our group viewed the Hotel del Coronado where Billy Wilder filmed Some Like It Hot and observed how the San Diego Zoo pioneered successful giant panda breeding and open-air cage-less exhibits that recreate natural habitats for mammals and tropical birds.

Torrey Pines State Natural Reserve, a 2000-acre coastal plateau with cliffs overlooking the ocean, contains the wildest stretch of land remaining in Southern California. Our ranger-guided tour of some trails revealed cacti, chaparral, the rare Torrey pine, and shy rattlesnakes. La Jolla, an upscale seaside resort known for its rugged coastline and hundreds of seals, engaged me because Iowa educator Henry Sabin retired here in the early 20th century. At the Birch Aquarium, we observed 5000 fish in more than sixty habitats. After dinner, the Artisan Winds, a San Diego State University (SDSU) chamber group, topped off our day. The next morning SDSU Chefs explaining how food preparation is “A Matter of Taste” concluded the program.

The Blue Ridge Mountains exploded in fall color during our weeklong program at Asheville, North Carolina, in October 2016 with twenty-eight Road Scholars. Founded in 1792, the city remained small until the railroad made it “the TB capital” by 1900. It boomed in the Twenties, erecting a notable Neo-Classical county court house and city hall. Civic-minded businessmen saved the historic downtown in the Sixties, turning many structures into commercial and residential properties. It became a popular retirement spot in the Nineties, ranking second to Santa Fe in the number of artists and galleries. We visited novelist Thomas Wolfe’s boyhood home, the Spanish Baroque Catholic Basilica of St. Lawrence, and Biltmore finished by George Vanderbilt II in 1895. Most of the 1.4 million annual visitors come to see the four-story, 450-room mansion modeled on French Renaissance Chateaus. It is furnished richly with tapestries, prints, paintings, carpets, and decorative objects. The two-story library has 10,000 volumes. A basement bowling alley, heated swimming pool, and gymnasium entertained guests. Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead designed seventy-five acres of formal gardens. Vanderbilt’s 125,000-acre self-sustaining estate had scientific forestry programs, a dairy; poultry, cattle, and hog farms; and Biltmore Village with cottages rented to workers. An excellent, pricey dinner enhanced by splendid views from the Sunset Terrace at the historic Grove Park Inn concluded our program. Concordia colleague James Lawton Haney entertained us for the weekend at his 1879 farm home near Marion, North Carolina.

Daughter Rachel joined seventeen others and us in February 2017 for the ten-day Road Scholar program, “The Best of Cuba.” Just as out Soviet Union Intourist guide Olga had done, Cuban State Guide Enedis Tanayo traveled with us throughout our trip. She carefully presented the government point of view while slyly pointing out many shortcomings. Castro’s Revolution displaced many middle-class and wealthy Cubans to Miami; it also established effective public health and public education systems. Yet starvation conditions set in after 1990 when the Soviet Union collapsed and ended Cuban aid. Che Guevara’s images are everywhere while pictures of Fidel are rarely seen by his own command. While Cubans will not speak openly about the government, they willingly share their hopes for a better future and closer ties with the American people. Cuban arts are vibrant. Flamenco dancers at a Camaguey dance studio set the beat for the house band as they performed. We heard the Cienfuegos Choir sing and answer audience questions. At a Havana Dance Company demonstration, we conversed with members individually. A contemporary art exhibit at the Havana Museum of Fine Art surprisingly displayed works critical of the Cuban Revolution’s unfinished business. A musicologist stressed the African, Indian, and Spanish character of Cuban music and its worldwide importance.

The state-owned 25,000-acre King Ranch leased smaller plots to peasants for goat and charcoal production when drought curtailed cattle grazing. Workers welcomed us with food and drink. The nearby village primary school displayed a bust of Cuban nationalist hero Jose Marti. Cubans need ration cards for basic food staples rice, beans, and cooking oil at shops, which often have empty shelves. State-run stores sell appliances that few can afford. Raúl Castro privatized 24 percent of the economy, enabling farmers to sell directly to consumers and others to operate small restaurants and hotels. Our tips and leftovers at Paladors (private restaurants) helped feed the kitchen and wait staff, as did the $10 or $20 we expended on CDs sold by the house bands. Many Cuban colonial churches are well-maintained World Heritage sites. Most Cubans are nominally Catholic. Papal visits by Pope John Paul II (1998), Pope Benedict XVI (2012), and Pope Francis (2015) energized Catholic social activism. The church is the largest non-state social service provider, sponsoring national aid programs, medical dispensaries, retirement homes, and community-based soup kitchens for Cuba’s most needy. At Alex Castro’s Havana restaurant, Fidel’s youngest son, an environmental activist and photographer, expressed hope for closer relations between Cubans and Americans. Cuban-American guide Alex wanted elections restored and Cuban guide Enedis dreamed of shopping for a vast choice of low-priced goods at Walmart. Sadly, the Cuban and United States governments have frustrated these hopes.

During 2018 and 2019, Jo and I embarked on Road Scholar tours of countries occupied by what Winston Churchill called “the English speaking peoples.” On a twenty-two day February visit to Australia and New Zealand, we learned both are highly scenic and have a lot more turnip-eating sheep than beer-drinking people. At our Melbourne Mercure Hotel the group of nine Midwesterners and four Westerners bonded quickly. Retired lawyer Richard De Gille’s political and economic overview of contemporary Australia prepared us for what we saw during the next nine days. Our leader, retired school principal Robyn Kidd, proudly showed off her country. Our bus driver on the Great Ocean Road to Adelaide entertainingly informed us about the striking sea- and arid pastoral landscapes. During free days in Melbourne, Jo and I walked about conversing with people at inexpensive venues like the Fitzroy Gardens, St. Patrick’s Catholic Cathedral, Treasury Museum, State Library, and a Scottish Church of Christ. At the Adelaide botanical garden an aboriginal guide told us how his people had used plants for food and medicine, and how conditions had deteriorated under the current rightwing government. In Sydney, we walked through Hyde Park, the Botanical Garden and New South Wales Art Museum, where a docent explained aboriginal art, and enjoyed a guided tour of the world-renowned Sydney Opera House. Speaking with a White nationalist yet anti-Trump student on the Sydney Harbor Ferry jarred my otherwise favorable impressions of Australians.

At Auckland, New Zealand, an urban walkabout took us to the large park-like Auckland Domain by way of the university where new international students were enrolling. We dropped in at the nearby Anglican Church and talked with the female associate pastor. A Mouri man tried (unsuccessfully) to teach us the language. The New Zealand Program began with a hearty noon meal at the Grand Mercure Hotel for the group of twenty-four. Published author and retired history professor Hugh Davis coincidentally held a 1969 doctorate in American Intellectual History. His leftwing political views made him fun to talk with until his wife pushed the off button. Newspaperman Gordon McLauchlan dispensed copies of A Short History of New Zealand, and gave a dryly-condensed version of it. At a North Island Nature Reserve, we shared in the traditional Maori welcome and a guide explained his culture and its use of native plants. A War Memorial Museum docent later told us more about Polynesian artifacts and settlement patterns. At Christ Church on the South Island, we toured the International Antarctic Center, which aimed to replicate living conditions there. En route to the Rendezvous Hotel, we saw effects of the 2012 earthquakes and how community-led projects rejuvenated the city. A motor coach took us to Banks Peninsula and Akaroa, a historic French and British town sited in the heart of an ancient volcano. An evening tour and dinner at the historic Riccarton House, a significant early Christ Church homestead, concluded our stay.

We next bussed across the fertile Canterbury Plains dotted by prosperous farms through the Rakaia Gorge to the stunning mountain vistas of Lake Tekapo at the heart of the International Dark Sky Reserve. At midnight, we toured the observatory on the summit of Mt. John without being able to view the southern sky. Pictures are a poor substitute! At Akoraki Mount Cook, we visited the Sir Edmund Hillary Alpine Center, and had a nature hike. Queenstown, “adventure capital of the world,” sits on the shores of Lake Wakatipu surrounded by the Remarkables and Eyre mountain ranges. From there, we joined many other tourists on a tiring eight-hour drive through Te Annau on a spectacular Alpine route to Milford Sound for a cruise with commentary. A Queenstown walkabout took Jo and me to the Gardens, Harbor, Skyline Gondola, cemetery, Asian market selling Ben & Jerry’s ice cream, and lakeshore trail back to the hotel. A farewell dinner took place at the Gibbston Valley Winery where wine tasting preceded the food. Visiting a gold mining camp en route to the airport concluded our trip “down under.”

The Inspirational England Road Scholar Program began at the Salisbury Red Lion Hotel. It had a lovely courtyard, 16th century vines, and a grumpy barman who dismissed lager as fake beer. Our group of seventeen hailed from seven states and Canada. Guide Ruth Polling showed us the inspiring Salisbury Cathedral, Stonehenge, the monumental stone circle at Avebury, and a ruined Norman castle William the Conqueror had built on the site of an iron-age fort. During two hours traversing greater London by bus, Jo and I observed how much the skyline and city had changed over three decades since our last visit. Buckingham Horse Guards stabling their mounts in a high-rise apartment near the palace surprised two former farm kids. Natural light from plain glass windows clearly displayed Christopher Wren’s interior architectural details thanks to the laborious cleaning of the St. Paul’s Cathedral. After examining the United States War Memorial located behind the high alter, our tour ended in the crypt at the Wren, Lord Nelson, and Duke of Wellington tombs. William the Conqueror built the Tower of London in 1078 to guard the River Thames. Henry VIII imprisoned and executed Thomas More, Anne Boleyn, and other notables here. Today the Tower is best known for displaying the Crown Jewels, which had to be remade for Charles II after Cromwell and the Puritans melted them down during the English Civil War. A guided river cruise from the tower to Westminster Pier took Jo and I to visit the Churchill war rooms with steel I-beam reinforced ceilings in the basement of White Hall. Exhibits documented his earlier military, journalistic, literary, and political careers.

At Cambridge, a guide explained the Tudor iconography of King’s College Chapel. After several days of uncharacteristic English sunshine and cloudless blue skies, weather turned cold at Burghley House built in the 16th century by William Cecil, Lord Treasurer to Elizabeth I. Rain kept us from the 18th century gardens designed by “Capability” Brown. Our later guided tour of the woodland and rose gardens, fountains, and lakes at Castle Howard made up for this omission. Its interior paled in comparison to the more richly furnished Burghley House. During three-nights at the Crown Plaza Hotel in the former spa city of Harrowgate, we had a splendid view of the English countryside from our fourth floor room. New guide Sarah walked us about York, an old Roman city. At least three Roman emperors visited, and Constantine was crowned there. We observed Roman and Saxon ruins, and the mostly extant medieval city wall erected in 1300. Majestic York Minster is the second largest Gothic cathedral in Northern Europe. From York we bussed through the heather landscape of North York Moors National Park. At Goatherd Station, a steam locomotive puffed its way up the narrow valley as it had in a Harry Potter movie. At the picturesque seaside town of Whitby, we walked up the steep escarpment to the ruins of Whitby Abbey, the inspiration for Bram Stoker’s Dracula. A synod met at this spot in the 6th century to decide the date for celebrating Easter. Ruins of the 12th century Saxon Abbey still remain. The fifty-five mile drive north to Hadrian’s Wall on another sunny day took us through the beautiful landscapes of County Durham and Northumberland best known to us from the English mystery series, Vera. We followed the wall through wild terrain to Chester, and the best-preserved Roman cavalry fort in Britain. The wall and ruins testify to Roman engineering and building skills. Durham Cathedral and Castle, sited on a rocky promontory overlooking the river and medieval city, served the crown’s political and military needs on the northern border.

At Ripon, a small cathedral city, the 7th century church feels more intimate than other cathedrals because it has a smaller proportion of tourists compared to local Christians. The red-poppy-decorated pulpit and an art exhibition commemorated the Great War 100th centenary.

Our two-week May tour of Scotland ranks as our best Road Scholar trip. The group of twenty-five came from all parts of the United States. Group leader Medea Muller, a lovely Swiss German woman, instructor Alasdair MacDonald, and “Wee Stevie,” the bus driver, completed the team that cared for us wonderfully as we traveled from Glasgow through the Scottish highlands to Edinburgh. A lecture on Scottish history and a bus tour of Glasgow ended with an impressive thirty-minute concert on the world-famous Kelvingrow Museum Organ. We next bussed southwest to Culzean Castle—a great house of the Kennedy family—on the Firth of Clyde. The Scots gave Dwight Eisenhower a lifetime residence here for his military leadership during World War II. At an afternoon stop at Alloway to see Robert Burns’ cottage and museum, Alasdair read Burns poetry with great feeling. We later toured the 18th century Inverarary Castle and St. Conan’s Kirk associated with the Campbell Clan. At Iona, we viewed ruins of the monastery St. Columbia founded in 563 as well as the still standing church. A taste of Bell’s Whisky enhanced our sunny private cruise of Loch Shiel. The loch is the Hogwarts setting for Harry Potter movies. Nearby the steam-powered Jacobite (Hogwarts) Express passes over the Glenfinnan Viaduct. A lakeside monument memorializes Jacobite clansmen who fought for Bonnie Prince Charley. Neptune’s Staircase—locks for the Caledonian Canal built between 1815 and 1822—doubled trade between the East and West Scottish coasts.

Clouds, wind, and cold spoiled our gondola ride to the Ben Nevis Mountain Lookout and kept us from seeing Northern Ireland. The West Highland train carried us on Scotland’s most scenic trip from Fort William to Crianlarich. We bussed back to Fort William through a striking landscape of moor and mountain under heavy rain-threatening clouds. At Glencoe, Alasdair recounted how English massacred thirty Clan Macdonald members for refusing to swear fealty to the new British monarchs William and Mary. We motored two hundred miles through ten-hours of splendid highland scenery to Tulloch Castle near Dingwall on the East Coast by way of the Isle of Sky on the West Coast. The Urquhart Castle ruins on Loch Ness date to the coming of Christianity in the 6th century. A Jacobite rising destroyed the structure in 1689. Tulloch Castle, the 12th century home of the Clan Davidson, featured excellent food, a ghost tour, and a concert in the great hall by a local ensemble of eighteen musicians celebrating Gaelic culture, music, and song. Cawdor Castle centered on a 15th Century Tower and its 18th and 19th century rationalist and romantic gardens. The Culloden Battlefield and its Visitor Center cinema technology facilitated experiencing how British field guns decimated Jacobite ranks and ended Charles Stuart’s threat to the British throne. Heading south to Edinburgh, we stopped at the Glen Ord Distillery, Leault Farms to watch working sheep dogs, Dunkeld Cathedral and Birnan Wood, and Scone Palace and gardens where Scottish kings were crowned until Charles II. The stone Rosslyn Chapel is one of the most picturesque in Great Britain.

After a guided bus tour of the city, Alasdair led us on foot to the highest level of Edinburgh Castle and turned us loose when the sun came out. Jo and I visited the Crown jewels, royal apartments, National War Monument, Long Hall, and Margaret’s Chapel, and took in an excellent panoramic view of the city. Alasdair met the group at St. Giles Church after lunch and gave us a two-hour guided walking tour along the Royal Mile, pointing out a statue of Charles II in Roman Imperial garb; a statue of Adam Smith; the house of John Knox and his parking lot burial spot; and the Scottish Parliament Building. At our final group meeting, everyone overflowed with good will for our group leaders Alasdair and Medea. Sadly, we returned home to the news longtime friend Les Meyer had died. Thankfully, we arrived in time for his funeral.

“Ireland: The Coast, Countryside, and Dublin” Road Scholars numbered twenty-one. We met over dinner at the Killarney International Hotel. A guided excursion took us around the Ring of Kerry. Low-hanging clouds and rain did not detract from the beautiful sea- and landscape. A typically hearty Road Scholar lunch of smoked salmon, brown bread, potato salad, cole slaw, and tea at the Blind Piper in the seaside town of Caherdaniel ensured that a pint of lager at the hotel bar sufficed for supper, A competent park service woman hiked us through the Killarney National Park, teaching about bats, trees, rutting Red Deer, and other animals. Rachel and Diarmand Healy hosted four of us for dinner, Per Irish custom she waited on us without sitting down to eat. Her husband appeared briefly and said little. A Yorkshire terrier was heard but not seen. Rachel responded to our queries about work, inquired about our trip, indicated her favorite places, talked about a difficult delivery, and proudly displayed her infant daughter. Heavy skies again darkened the picturesque landscape on our way to Dingle Peninsula and town. David Lean’s filming of Ryan’s Daughter, winner of two academy awards, put both on the tourist map. En route to Galway—the cradle of Gaelic culture in western Ireland—we saw the spectacular Cliffs of Moher and the Burren, a glaciated limestone area in County Clare famed for its unique flora and archaeological remains including hill forts, beehive huts, and a corbel vaulted stone chapel built by monks between the 7th and 9th centuries.

At Galway, a pretty actor poetically described An Taibhdhearc, the national Irish language theatre. Expert city guide Liam Silke highlighted the Spanish Arch, part of the original city wall, St. Nicholas Cathedral, and Eyre Park. We had a steak dinner at Glenlo Abbey and heard a Montana-born Irish academic describe the salon poet W. B. Yeats and widow Augusta Gardner conducted there. Following a rough morning ferry ride to Inis Mor, we braved wind and rain on a strenuous hike to a Bronze Age hill fort and also toured ruins of seven churches dating to the Middle Ages. On a picturesque drive to Dorrians Imperial Hotel at Ballyshannon (1781) in County Donegal, our bus stopped at Yeats’ final resting place under majestic Ben Bulben Mountain. An evening of Irish music and dance at a local pub featured two accordions, two fiddles, and two guitars. Beautiful coastal scenery highlighted the drive to Glencolmeille, a remote, lightly populated place chosen by the patron St Columbia for his ministry. A Chicago-born widow of a local sheep farmer guided our tour of a church and other local sites. Most interesting were the watchtowers built to warn of an expected French invasion during the Napoleonic Wars. We crossed into Northern Ireland from Ballyshannon. At the marvelous Ulster Folk Museum, we enjoyed a self-guided tour of an outdoor display of houses, churches, schools, and villages from which the Irish emigrated as well as American city streets and farms to which they immigrated. Many reenactors answered questions along the way.

A literary walking tour on a cold, drizzly day introduced us to Dublin through the lives of James Joyce, W. B. Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde, and others. We ended at the National Museum and viewed the W. B. Yeats exhibition followed later by an excellent one-person, one-act play about Molly Allgood’s life with a theatrical director. Rain did not prevent next morning’s walk to the National Museum of Archeology for a two-hour session examining the Stone, Viking, and Anglo-Norman ages in Ireland. An entertaining tour of city history followed at the little Museum of Dublin. At the National Art Museum, Jo and I learned how art before 1800 featured Anglo-Irish lives and focused on ordinary Irish lives thereafter. The General Post Office offered an excellent technologically sophisticated new exhibit about the Easter Uprising. Afterward, we viewed the Dublin Castle (seat of British rule since the time of King John) and the Protestant Christ Church and Catholic St. Patrick’s cathedrals dating to the 12th century. Over our usual pre-dinner pint at the Camden Court Hotel, Kevin, a California developer, told how he always dealt carefully with the Trump Organization, which did business like Donald ran the White House—shadily. Our trip home the next day went well until Minneapolis where our Fargo flight was delayed two hours. A jammed door prevented collecting our luggage after landing. Disgusted, we went home without bags and fell into bed exhausted at 1:30 a.m. (CDT). Wonderful Road Scholars experiences shared nevertheless justified all the discomforts suffered on this harrowing twenty-four-hour home-going marathon.

The COVID-19 Pandemic suspended our international travels perhaps forever. We had planned a two-week “Aegean Adventure” to Greece, Crete, and Santorini in September 2020 with former Concordia College Art History Professor Peter Schultz. Although rescheduled for 2022 after being postponed twice, we prudently cancelled our reservation rather than risk throwing $10,000 away. Hematologist/Oncologist Ammar Alzoubi had waited and observed my abnormally low blood counts decline for several years without ordering a bone marrow biopsy, making a diagnosis, and prescribing treatment. When my numbers dropped more sharply, I feared being physically unable to travel in a few months. So, I cancelled our reservation, planned our funerals and prepaid our expenses, and completed drafts of two books I had been writing. I deposited Schooling in the archives at Concordia College, University of Northern Iowa, and the University of Iowa, and self-published By the Sweat of His Brow, which I devoted 2023 to marketing. Hematologist/ Oncologist Seth Maliske ordered a bone marrow biopsy in August and diagnosed MDS, a slow growing cancer that attacks red blood cells. The disease is treated with weekly shots to boost the red blood count, and the treatment is presently working. I am grateful for the reprieve, enabling me to revise Schooling for digital publication and to watch my grand twin grow into responsible adults. Perhaps I may even be on hand in 2025 to celebrate the graduation of Oscar and Annalise from Lakeville South High School as well as Gus and Cecilia from Washington University – St. Louis and Gustavas Adolphus College respectively.

Even as an octogenarian, I do not like contemplating death. As a child, I wondered how my grandparents and other elderly folk regarded their lives ending. I did not ask and they did not offer any information at funerals beyond “it comes to us all.” They paused to pay their respects, and then resumed their daily lives despite infirmities of age. Like them, I avoid thoughts of annihilation by pursuing purposeful projects as long as I am able. I regularly attend Sunday worship, Concordia emeriti luncheons and other college events, and quarterly cemetery board meetings. I read articles from the American Historical Review, Journal of American History, New York Review of Books, and Newsweek as well as add book titles to the 3700 items on the Books Read list I have kept for more than a half century To be sure, dozing off more frequently while reading or watching TV has increased with age. We rarely attend movie theatres as my hearing grows more impaired, and rely on Cable Television for watching movies, series, British mysteries, documentaries, and sporting events—Iowa Hawkeye football, men’s basketball, and women’s basketball as well as the Minnesota Vikings, Lynx, Timberwolves, and Twins. Netflix streaming and PBS Passport supplies us with ample quality choices. During our childhood, television was reputed to be a wasteland; yet we find more high quality entertainment in our old age than we did when we were young.

Grandchildren are God’s compensation for growing old. We still visit them regularly at Lakeville on holidays when Cecilia and Gus are home from college and to watch Oscar’s lacrosse matches and basketball games and Annalise’s cross country and track meets. Daughter Kristen and son-in-law Todd live on an eighty-acre farmstead where they have built an ecologically designed house and a barn. Spending time at Barn Dance Farm evokes treasured childhood memories for me. In addition, Kristen planned a family trip to Traverse City, Michigan, in August 2023, where we celebrated our 60th wedding anniversary. For Summer 2024 she booked us on a cruise from Anchorage, Alaska, to Vancouver, British Columbia.

Younger daughter Rachel abandoned urban civilization for beautiful Glacier Park in Montana upon graduating from St. Olaf College. After working three summers at Park Café and Grocery in St. Mary, she became a year-round waitress and bartender at Firebrand Pass Food & Ale near East Glacier Park Village for twenty-five years. Jo and I have trekked west nearly every summer to visit. We book rooms at the Mountain Pine Motel where Rachel now works. It is owned and operated by the Sherburne family, descended from original European settlers to the region. A stand of pines shades the simply furnished wood-paneled rooms and eliminates need for air-conditioning. We prefer its simplicity to the pricey Great Northern Lodge magnate Louis Hill built to attract tourists as passengers for his railroad. East Glacier, a small hamlet located on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation, numbers about four hundred people in the winter and usually triples in size during the short May through September tourist season. The stunning Glacier Park scenery often attracts several characters, reminiscent of the TV program Northern Exposure.

Initially, we traveled west on “the Hi-Line” (Highway 2) that followed James J. Hill’s Great Northern transcontinental rail line across northern Montana. Eventually, we settled on taking Interstate 94 to Glendive, Highway 200 across central Montana through Lewistown to Great Falls, Interstate 15 north to “the Valier cutoff” to Highway 89 that tracks north along the Rocky Mountain Front to Browning, and finally Highway 2 into East Glacier. Since growing too old for completing this nearly nine hundred miles in a single thirteen-hour day, we overnight at Lewistown going out and Dickinson, North Dakota, coming home. When we can no longer drive our own car, Amtrak is not a viable alternative. It arrives and departs Fargo in the middle of the night and is often delayed by freight trains given track priority.

Whenever death comes, I am grateful for a reasonably well-lived four score years. Schooling took me from my parents’ small Iowa farm; gave me a college teaching career spanning five decades; facilitated publishing several historical books, articles, and reviews; and enabled traveling to four continents, twenty-five countries, forty-five states, and one United States territory. A man additionally blessed with two daughters, a son-in-law, and four grand twins should not complain whenever and however his life ends.