4 Chapter 4: Biology

|

|

Purpose |

|

Warm-up |

Your brain actually remembers information better if it warms up. You warm up your brain by preparing it for the academic activity that it must do. If you are preparing for a discussion, for example, you can ask yourself, “Why is my instructor going to have a discussion? What do they hope I will ‘get out’ of this discussion?”

|

|

Work out |

In academics, the purpose of the workout is to learn the material you need to know in order to be successful in the class. This might involve reading, jotting down ideas you might wish to share in discussion, or taking notes on a lecture.

|

|

Cool Down |

In academics, the purpose of a cool down is to do two things—one, make some decisions about what you did during your workout that is important enough to remember and two, plan ahead. What will you need to study tomorrow? What confuses you and how can you get help with your confusion?

|

Warm Up:

What is my instructor going to ask me to do? What do they hope I will ‘get out’ of this chapter and unit?” Read the Review Questions at the end of Chapter 1 The Study of Life. What do you need to know by the time you finish reading this chapter?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Academic Skill: Focus on Reading

A good college reader warms up, works out then cools down. Here is how that process applies to reading college level material:

|

|

Activity |

|

Warm-up |

To warm up your brain, spend a few minutes looking over the material you need to read. Read the headings and subheadings. Look at graphics and pictures if there are any. Ask yourself “What will I be learning in this reading?” “What ideas seem to be important?”

|

|

Work out |

To work out in reading, you need to read! But it isn’t that simple. You need to have a note taking strategy that will allow you to do two things: 1) Figure out what information is most important and 2) Remember that information.

|

|

Cool Down |

To cool down in reading, see what you can remember about the reading by stating main ideas in your own words, telling a friend what you learned or asking yourself “Which ideas did I read tonight are so important they might end up on an exam?” You can also make a list of things that confused you that you can ask your instructor or a tutor.

|

Warm up

The three strategies described below should be used before you actually read. You might wish to do just one strategy, or it might make sense to use more than one.

Work out

While you are reading, you can’t simply run your eyes over the words and expect to retain anything anymore than you can expect to sit quietly in the corner at a choir rehearsal and learn the songs. While you read, you need to have a way to interact with the material so you can remember it.

Cool down

Many students make the mistake of completing the read they have to do for a particular day, closing the book and moving on to the next task. This is like the athlete who leaves practice before the cool down! In addition to risking injury to her muscles, this athlete also misses the end of practice conversations about what the team is doing well and what practices will emphasize in the future. Students need to have a cool down to make sure they understand what they read that day and to think about what some good ways are to study in the days to come.

Reading: THE STUDY OF LIFE

Figure 1.1 This NASA image is a composite of several satellite-based views of Earth. To make the whole-Earth image, NASA scientists combine observations of different parts of the planet. (credit:

NASA/GSFC/NOAA/USGS)

|

Chapter Outline |

|

1.1: The Science of Biology 1.2: Themes and Concepts of Biology |

Introduction

Viewed from space, Earth offers no clues about the diversity of life forms that reside there. The first forms of life on Earth are thought to have been microorganisms that existed for billions of years in the ocean before plants and animals appeared. The mammals, birds, and flowers so familiar to us are all relatively recent, originating 130 to 200 million years ago. Humans have inhabited this planet for only the last 2.5 million years, and only in the last 200,000 years have humans started looking like we do today.

1.1 | The Science of Biology

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

Identify the shared characteristics of the natural sciences

Summarize the steps of the scientific method

Compare inductive reasoning with deductive reasoning

Describe the goals of basic science and applied science

(a)(b)

Figure 1.2 Formerly called blue-green algae, these (a) cyanobacteria, shown here at 300x magnification under a light microscope, are some of Earth’s oldest life forms. These (b) stromatolites along the shores of Lake Thetis in Western Australia are ancient structures formed by the layering of cyanobacteria in shallow waters. (credit a: modification of work by NASA; credit b: modification of work by Ruth Ellison; scale-bar data from Matt Russell)

What is biology? In simple terms, biology is the study of living organisms and their interactions with one another and their environments. This is a very broad definition because the scope of biology is vast. Biologists may study anything from the microscopic or submicroscopic view of a cell to ecosystems and the whole living planet (Figure 1.2). Listening to the daily news, you will quickly realize how many aspects of biology are discussed every day. For example, recent news topics include Escherichia coli (Figure 1.3) outbreaks in spinach and Salmonella contamination in peanut butter. Other subjects include efforts toward finding a cure for AIDS, Alzheimer’s disease, and cancer. On a global scale, many researchers are committed to finding ways to protect the planet, solve environmental issues, and reduce the effects of climate change. All of these diverse endeavors are related to different facets of the discipline of biology.

Figure 1.3 Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria, seen in this scanning electron micrograph, are normal residents of our digestive tracts that aid in the absorption of vitamin K and other nutrients. However, virulent strains are sometimes responsible for disease outbreaks. (credit: Eric Erbe, digital colorization by Christopher Pooley, both of USDA, ARS, EMU)

The Process of Science

Biology is a science, but what exactly is science? What does the study of biology share with other scientific disciplines? Science (from the Latin scientia, meaning “knowledge”) can be defined as knowledge that covers general truths or the operation of general laws, especially when acquired and tested by the scientific method. It becomes clear from this definition that the application of the scientific method plays a major role in science. The scientific method is a method of research with defined steps that include experiments and careful observation.

The steps of the scientific method will be examined in detail later, but one of the most important aspects of this method is the testing of hypotheses by means of repeatable experiments. A hypothesis is a suggested explanation for an event, which can be tested. Although using the scientific method is inherent to science, it is inadequate in determining what science is. This is because it is relatively easy to apply the scientific method to disciplines such as physics and chemistry, but when it comes to disciplines like archaeology, psychology, and geology, the scientific method becomes less applicable as it becomes more difficult to repeat experiments.

These areas of study are still sciences, however. Consider archeology—even though one cannot perform repeatable experiments, hypotheses may still be supported. For instance, an archeologist can hypothesize that an ancient culture existed based on finding a piece of pottery. Further hypotheses could be made about various characteristics of this culture, and these hypotheses may be found to be correct or false through continued support or contradictions from other findings. A hypothesis may become a verified theory. A theory is a tested and confirmed explanation for observations or phenomena. Science may be better defined as fields of study that attempt to comprehend the nature of the universe.

Natural Sciences

What would you expect to see in a museum of natural sciences? Frogs? Plants? Dinosaur skeletons? Exhibits about how the brain functions? A planetarium? Gems and minerals? Or, maybe all of the above? Science includes such diverse fields as astronomy, biology, computer sciences, geology, logic, physics, chemistry, and mathematics (Figure 1.4). However, those fields of science related to the physical world and its phenomena and processes are considered natural sciences. Thus, a museum of natural sciences might contain any of the items listed above.

Figure 1.4 The diversity of scientific fields includes astronomy, biology, computer science, geology, logic, physics, chemistry, mathematics, and many other fields. (credit: “Image Editor”/Flickr)

There is no complete agreement when it comes to defining what the natural sciences include, however. For some experts, the natural sciences are astronomy, biology, chemistry, earth science, and physics. Other scholars choose to divide natural sciences into life sciences, which study living things and include biology, and physical sciences, which study nonliving matter and include astronomy, geology, physics, and chemistry. Some disciplines such as biophysics and biochemistry build on both life and physical sciences and are interdisciplinary. Natural sciences are sometimes referred to as “hard science” because they rely on the use of quantitative data; social sciences that study society and human behavior are more likely to use qualitative assessments to drive investigations and findings.

Not surprisingly, the natural science of biology has many branches or subdisciplines. Cell biologists study cell structure and function, while biologists who study anatomy investigate the structure of an entire organism. Those biologists studying physiology, however, focus on the internal functioning of an organism. Some areas of biology focus on only particular types of living things. For example, botanists explore plants, while zoologists specialize in animals.

Scientific Reasoning

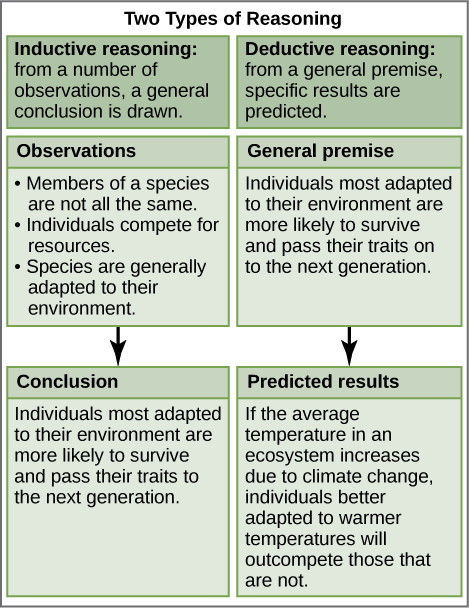

One thing is common to all forms of science: an ultimate goal “to know.” Curiosity and inquiry are the driving forces for the development of science. Scientists seek to understand the world and the way it operates. To do this, they use two methods of logical thinking: inductive reasoning and deductive reasoning.

Inductive reasoning is a form of logical thinking that uses related observations to arrive at a general conclusion. This type of reasoning is common in descriptive science. A life scientist such as a biologist makes observations and records them. These data can be qualitative or quantitative, and the raw data can be supplemented with drawings, pictures, photos, or videos. From many observations, the scientist can infer conclusions (inductions) based on evidence. Inductive reasoning involves formulating generalizations inferred from careful observation and the analysis of a large amount of data. Brain studies provide an example. In this type of research, many live brains are observed while people are doing a specific activity, such as viewing images of food. The part of the brain that “lights up” during this activity is then predicted to be the part controlling the response to the selected stimulus, in this case, images of food. The “lighting up” of the various areas of the brain is caused by excess absorption of radioactive sugar derivatives by active areas of the brain. The resultant increase in radioactivity is observed by a scanner. Then, researchers can stimulate that part of the brain to see if similar responses result.

Deductive reasoning or deduction is the type of logic used in hypothesis-based science. In deductive reason, the pattern of thinking moves in the opposite direction as compared to inductive reasoning. Deductive reasoning is a form of logical thinking that uses a general principle or law to forecast specific results. From those general principles, a scientist can extrapolate and predict the specific results that would be valid as long as the general principles are valid. Studies in climate change can illustrate this type of reasoning. For example, scientists may predict that if the climate becomes warmer in a particular region, then the distribution of plants and animals should change. These predictions have been made and tested, and many such changes have been found, such as the modification of arable areas for agriculture, with change based on temperature averages.

Both types of logical thinking are related to the two main pathways of scientific study: descriptive science and hypothesis-based science. Descriptive (or discovery) science, which is usually inductive, aims to observe, explore, and discover, while hypothesis-based science, which is usually deductive, begins with a specific question or problem and a potential answer or solution that can be tested. The boundary between these two forms of study is often blurred, and most scientific endeavors combine both approaches. The fuzzy boundary becomes apparent when thinking about how easily observation can lead to specific questions. For example, a gentleman in the 1940s observed that the burr seeds that stuck to his clothes and his dog’s fur had a tiny hook structure. On closer inspection, he discovered that the burrs’ gripping device was more reliable than a zipper. He eventually developed a company and produced the hook-and-loop fastener popularly known today as Velcro. Descriptive science and hypothesis-based science are in continuous dialogue.

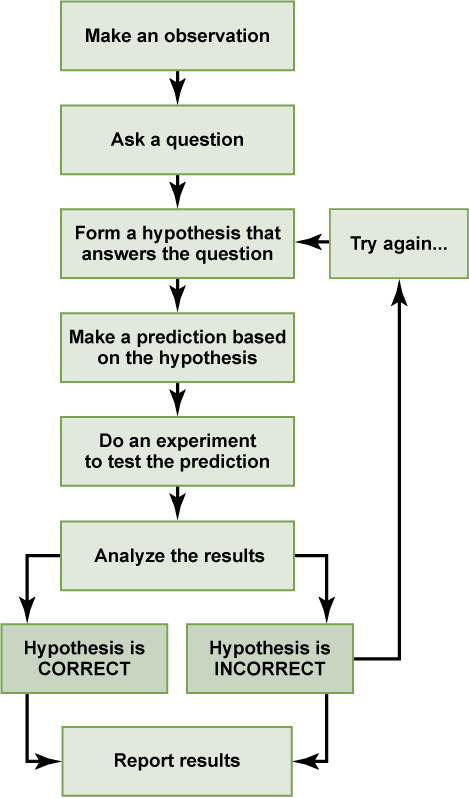

The Scientific Method

Biologists study the living world by posing questions about it and seeking science-based responses. This approach is common to other sciences as well and is often referred to as the scientific method. The scientific method was used even in ancient times, but it was first documented by England’s Sir Francis Bacon (1561–1626) (Figure 1.5), who set up inductive methods for scientific inquiry. The scientific method is not exclusively used by biologists but can be applied to almost all fields of study as a logical, rational problem-solving method.

Figure 1.5 Sir Francis Bacon (1561–1626) is credited with being the first to define the scientific method. (credit: Paul van Somer)

The scientific process typically starts with an observation (often a problem to be solved) that leads to a question. Let’s think about a simple problem that starts with an observation and apply the scientific method to solve the problem. One Monday morning, a student arrives at class and quickly discovers that the classroom is too warm. That is an observation that also describes a problem: the classroom is too warm. The student then asks a question: “Why is the classroom so warm?”

Proposing a Hypothesis

Recall that a hypothesis is a suggested explanation that can be tested. To solve a problem, several hypotheses may be proposed. For example, one hypothesis might be, “The classroom is warm because no one turned on the air conditioning.” But there could be other responses to the question, and therefore other hypotheses may be proposed. A second hypothesis might be, “The classroom is warm because there is a power failure, and so the air conditioning doesn’t work.”

Once a hypothesis has been selected, the student can make a prediction. A prediction is similar to a hypothesis but it typically has the format “If . . . then . . . .” For example, the prediction for the first hypothesis might be, “If the student turns on the air conditioning, then the classroom will no longer be too warm.”

Testing a Hypothesis

A valid hypothesis must be testable. It should also be falsifiable, meaning that it can be disproven by experimental results. Importantly, science does not claim to “prove” anything because scientific understandings are always subject to modification with further information. This step—openness to disproving ideas—is what distinguishes sciences from non-sciences. The presence of the supernatural, for instance, is neither testable nor falsifiable. To test a hypothesis, a researcher will conduct one or more experiments designed to eliminate one or more of the hypotheses. Each experiment will have one or more variables and one or more controls. A variable is any part of the experiment that can vary or change during the experiment. The control group contains every feature of the experimental group except it is not given the manipulation that is hypothesized about. Therefore, if the results of the experimental group differ from the control group, the difference must be due to the hypothesized manipulation, rather than some outside factor. Look for the variables and controls in the examples that follow. To test the first hypothesis, the student would find out if the air conditioning is on. If the air conditioning is turned on but does not work, there should be another reason, and this hypothesis should be rejected. To test the second hypothesis, the student could check if the lights in the classroom are functional. If so, there is no power failure and this hypothesis should be rejected. Each hypothesis should be tested by carrying out appropriate experiments. Be aware that rejecting one hypothesis does not determine whether or not the other hypotheses can be accepted; it simply eliminates one hypothesis that is not valid (Figure 1.6). Using the scientific method, the hypotheses that are inconsistent with experimental data are rejected.

While this “warm classroom” example is based on observational results, other hypotheses and experiments might have clearer controls. For instance, a student might attend class on Monday and realize she had difficulty concentrating on the lecture. One observation to explain this occurrence might be, “When I eat breakfast before class, I am better able to pay attention.” The student could then design an experiment with a control to test this hypothesis.

In hypothesis-based science, specific results are predicted from a general premise. This type of reasoning is called deductive reasoning: deduction proceeds from the general to the particular. But the reverse of the process is also possible: sometimes, scientists reach a general conclusion from a number of specific observations. This type of reasoning is called inductive reasoning, and it proceeds from the particular to the general. Inductive and deductive reasoning are often used in tandem to advance scientific knowledge (Figure 1.7).

Figure 1.6The scientific method consists of a series of well-defined steps. If a hypothesis is notsupported by experimental data, a new hypothesis can be proposed.In the example below, the scientific method is used to solve an everyday problem. Orderthe scientific method steps (numbered items) with the process of solving the everydayproblem (lettered items). Based on the results of the experiment, is the hypothesis correct?If it is incorrect, propose some alternative hypotheses.1.ObservationQuestion2.3.Hypothesis (answer)4.Prediction5.Experiment6.Resulta.There is something wrong with the electrical outlet.b.If something is wrong with the outlet, my coffeemaker also won’t work when pluggedinto it.c.My toaster doesn’t toast my bread.d.I plug my coffee maker into the outlet.e.My coffeemaker works.f.Why doesn’t my toaster work?

Figure 1.6The scientific method consists of a series of well-defined steps. If a hypothesis is notsupported by experimental data, a new hypothesis can be proposed.In the example below, the scientific method is used to solve an everyday problem. Orderthe scientific method steps (numbered items) with the process of solving the everydayproblem (lettered items). Based on the results of the experiment, is the hypothesis correct?If it is incorrect, propose some alternative hypotheses.1.ObservationQuestion2.3.Hypothesis (answer)4.Prediction5.Experiment6.Resulta.There is something wrong with the electrical outlet.b.If something is wrong with the outlet, my coffeemaker also won’t work when pluggedinto it.c.My toaster doesn’t toast my bread.d.I plug my coffee maker into the outlet.e.My coffeemaker works.f.Why doesn’t my toaster work?

Figure 1.7Scientists use two types of reasoning, inductive and deductive reasoning, toadvance scientific knowledge. As is the case in this example, the conclusion from inductivereasoning can often become the premise for inductive reasoning.Decide if each of the following is an example of inductive or deductive reasoning.All flying birds and insects have wings. Birds and insects flap their wings as they move1.through the air. Therefore, wings enable flight.Insects generally survive mild winters better than harsh ones. Therefore, insect pests2.will become more problematic if global temperatures increase.Chromosomes, the carriers of DNA, separate into daughter cells during cell division.3.Therefore, DNA is the genetic material.Animals as diverse as humans, insects, and wolves all exhibit social behavior.4.Therefore, social behavior must have an evolutionary advantage.

Figure 1.7Scientists use two types of reasoning, inductive and deductive reasoning, toadvance scientific knowledge. As is the case in this example, the conclusion from inductivereasoning can often become the premise for inductive reasoning.Decide if each of the following is an example of inductive or deductive reasoning.All flying birds and insects have wings. Birds and insects flap their wings as they move1.through the air. Therefore, wings enable flight.Insects generally survive mild winters better than harsh ones. Therefore, insect pests2.will become more problematic if global temperatures increase.Chromosomes, the carriers of DNA, separate into daughter cells during cell division.3.Therefore, DNA is the genetic material.Animals as diverse as humans, insects, and wolves all exhibit social behavior.4.Therefore, social behavior must have an evolutionary advantage.

The scientific method may seem too rigid and structured. It is important to keep in mind that, although scientists often follow this sequence, there is flexibility. Sometimes an experiment leads to conclusions that favor a change in approach; often, an experiment brings entirely new scientific questions to the puzzle. Many times, science does not operate in a linear fashion; instead, scientists continually draw inferences and make generalizations, finding patterns as their research proceeds. Scientific reasoning is more complex than the scientific method alone suggests. Notice, too, that the scientific method can be applied to solving problems that aren’t necessarily scientific in nature.

Two Types of Science: Basic Science and Applied Science

The scientific community has been debating for the last few decades about the value of different types of science. Is it valuable to pursue science for the sake of simply gaining knowledge, or does scientific knowledge only have worth if we can apply it to solving a specific problem or to bettering our lives? This question focuses on the differences between two types of science: basic science and applied science.

Basic science or “pure” science seeks to expand knowledge regardless of the short-term application of that knowledge. It is not focused on developing a product or a service of immediate public or commercial value. The immediate goal of basic science is knowledge for knowledge’s sake, though this does not mean that, in the end, it may not result in a practical application.

In contrast, applied science or “technology,” aims to use science to solve real-world problems, making it possible, for example, to improve a crop yield, find a cure for a particular disease, or save animals threatened by a natural disaster (Figure 1.8). In applied science, the problem is usually defined for the researcher.

Figure 1.8 After Hurricane Ike struck the Gulf Coast in 2008, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service rescued this brown pelican. Thanks to applied science, scientists knew how to rehabilitate the bird. (credit: FEMA)

Some individuals may perceive applied science as “useful” and basic science as “useless.” A question these people might pose to a scientist advocating knowledge acquisition would be, “What for?” A careful look at the history of science, however, reveals that basic knowledge has resulted in many remarkable applications of great value. Many scientists think that a basic understanding of science is necessary before an application is developed; therefore, applied science relies on the results generated through basic science. Other scientists think that it is time to move on from basic science and instead to find solutions to actual problems. Both approaches are valid. It is true that there are problems that demand immediate attention; however, few solutions would be found without the help of the wide knowledge foundation generated through basic science.

One example of how basic and applied science can work together to solve practical problems occurred after the discovery of DNA structure led to an understanding of the molecular mechanisms governing DNA replication. Strands of DNA, unique in every human, are found in our cells, where they provide the instructions necessary for life. During DNA replication, DNA makes new copies of itself, shortly before a cell divides. Understanding the mechanisms of DNA replication enabled scientists to develop laboratory techniques that are now used to identify genetic diseases, pinpoint individuals who were at a crime scene, and determine paternity. Without basic science, it is unlikely that applied science would exist.

Another example of the link between basic and applied research is the Human Genome Project, a study in which each human chromosome was analyzed and mapped to determine the precise sequence of DNA subunits and the exact location of each gene. (The gene is the basic unit of heredity; an individual’s complete collection of genes is his or her genome.) Other less complex organisms have also been studied as part of this project in order to gain a better understanding of human chromosomes. The Human Genome Project (Figure 1.9) relied on basic research carried out with simple organisms and, later, with the human genome. An important end goal eventually became using the data for applied research, seeking cures and early diagnoses for genetically related diseases.

Figure 1.9 The Human Genome Project was a 13-year collaborative effort among researchers working in several different fields of science. The project, which sequenced the entire human genome, was completed in 2003. (credit: the U.S. Department of Energy Genome Programs

(http://genomics.energy.gov))

While research efforts in both basic science and applied science are usually carefully planned, it is important to note that some discoveries are made by serendipity, that is, by means of a fortunate accident or a lucky surprise. Penicillin was discovered when biologist Alexander Fleming accidentally left a petri dish of Staphylococcus bacteria open. An unwanted mold grew on the dish, killing the bacteria. The mold turned out to be Penicillium, and a new antibiotic was discovered. Even in the highly organized world of science, luck—when combined with an observant, curious mind—can lead to unexpected breakthroughs.

Reporting Scientific Work

Whether scientific research is basic science or applied science, scientists must share their findings in order for other researchers to expand and build upon their discoveries. Collaboration with other scientists—when planning, conducting, and analyzing results—are all important for scientific research. For this reason, important aspects of a scientist’s work are communicating with peers and disseminating results to peers. Scientists can share results by presenting them at a scientific meeting or conference, but this approach can reach only the select few who are present. Instead, most scientists present their results in peer-reviewed manuscripts that are published in scientific journals. Peer-reviewed manuscripts are scientific papers that are reviewed by a scientist’s colleagues, or peers. These colleagues are qualified individuals, often experts in the same research area, who judge whether or not the scientist’s work is suitable for publication. The process of peer review helps to ensure that the research described in a scientific paper or grant proposal is original, significant, logical, and thorough. Grant proposals, which are requests for research funding, are also subject to peer review. Scientists publish their work so other scientists can reproduce their experiments under similar or different conditions to expand on the findings. The experimental results must be consistent with the findings of other scientists.

A scientific paper is very different from creative writing. Although creativity is required to design experiments, there are fixed guidelines when it comes to presenting scientific results. First, scientific writing must be brief, concise, and accurate. A scientific paper needs to be succinct but detailed enough to allow peers to reproduce the experiments.

The scientific paper consists of several specific sections—introduction, materials and methods, results, and discussion. This structure is sometimes called the “IMRaD” format. There are usually acknowledgment and reference sections as well as an abstract (a concise summary) at the beginning of the paper. There might be additional sections depending on the type of paper and the journal where it will be published; for example, some review papers require an outline.

The introduction starts with brief, but broad, background information about what is known in the field. A good introduction also gives the rationale of the work; it justifies the work carried out and also briefly mentions the end of the paper, where the hypothesis or research question driving the research will be presented. The introduction refers to the published scientific work of others and therefore requires citations following the style of the journal. Using the work or ideas of others without proper citation is considered plagiarism.

The materials and methods section includes a complete and accurate description of the substances used, and the method and techniques used by the researchers to gather data. The description should be thorough enough to allow another researcher to repeat the experiment and obtain similar results, but it does not have to be verbose. This section will also include information on how measurements were made and what types of calculations and statistical analyses were used to examine raw data. Although the materials and methods section gives an accurate description of the experiments, it does not discuss them.

Some journals require a results section followed by a discussion section, but it is more common to combine both. If the journal does not allow the combination of both sections, the results section simply narrates the findings without any further interpretation. The results are presented by means of tables or graphs, but no duplicate information should be presented. In the discussion section, the researcher will interpret the results, describe how variables may be related, and attempt to explain the observations. It is indispensable to conduct an extensive literature search to put the results in the context of previously published scientific research. Therefore, proper citations are included in this section as well.

Finally, the conclusion section summarizes the importance of the experimental findings. While the scientific paper almost certainly answered one or more scientific questions that were stated, any good research should lead to more questions. Therefore, a well-done scientific paper leaves doors open for the researcher and others to continue and expand on the findings.

Review articles do not follow the IMRAD format because they do not present original scientific findings, or primary literature; instead, they summarize and comment on findings that were published as primary literature and typically include extensive reference sections.

1.2 | Themes and Concepts of Biology

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

Identify and describe the properties of life

Describe the levels of organization among living things

Recognize and interpret a phylogenetic tree

List examples of different sub disciplines in biology

Biology is the science that studies life, but what exactly is life? This may sound like a silly question with an obvious response, but it is not always easy to define life. For example, a branch of biology called virology studies viruses, which exhibit some of the characteristics of living entities but lack others. It turns out that although viruses can attack living organisms, cause diseases, and even reproduce, they do not meet the criteria that biologists use to define life. Consequently, virologists are not biologists, strictly speaking. Similarly, some biologists study the early molecular evolution that gave rise to life; since the events that preceded life are not biological events, these scientists are also excluded from biology in the strict sense of the term.

From its earliest beginnings, biology has wrestled with three questions: What are the shared properties that make something “alive”? And once we know something is alive, how do we find meaningful levels of organization in its structure? And, finally, when faced with the remarkable diversity of life, how do we organize the different kinds of organisms so that we can better understand them? As new organisms are discovered every day, biologists continue to seek answers to these and other questions.

Properties of Life

All living organisms share several key characteristics or functions: order, sensitivity or response to the environment, reproduction, growth and development, regulation, homeostasis, and energy processing. When viewed together, these eight characteristics serve to define life.

Order

Figure 1.10 A toad represents a highly organized structure consisting of cells, tissues, organs, and organ systems. (credit: “Ivengo”/Wikimedia Commons)

Organisms are highly organized, coordinated structures that consist of one or more cells. Even very simple, single-celled organisms are remarkably complex: inside each cell, atoms make up molecules; these in turn make up cell organelles and other cellular inclusions. In multicellular organisms (Figure 1.10), similar cells form tissues. Tissues, in turn, collaborate to create organs (body structures with a distinct function). Organs work together to form organ systems.

Sensitivity or Response to Stimuli

Figure 1.11 The leaves of this sensitive plant (Mimosa pudica) will instantly droop and fold when touched. After a few minutes, the plant returns to normal. (credit: Alex Lomas)

Organisms respond to diverse stimuli. For example, plants can grow toward a source of light, climb on fences and walls, or respond to touch (Figure 1.11). Even tiny bacteria can move toward or away from chemicals (a process called chemotaxis) or light (phototaxis). Movement toward a stimulus is considered a positive response, while movement away from a stimulus is considered a negative response.

Watch this video (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/movement_plants) to see how plants respond to a stimulus—from opening to light, to wrapping a tendril around a branch, to capturing prey.

Reproduction

Single-celled organisms reproduce by first duplicating their DNA, and then dividing it equally as the cell prepares to divide to form two new cells. Multicellular organisms often produce specialized reproductive germline cells that will form new individuals. When reproduction occurs, genes containing DNA are passed along to an organism’s offspring. These genes ensure that the offspring will belong to the same species and will have similar characteristics, such as size and shape.

Growth and Development

All organisms grow and develop following specific instructions coded for by their genes. These genes provide instructions that will direct cellular growth and development, ensuring that a species’ young (Figure 1.12) will grow up to exhibit many of the same characteristics as its parents.

Figure 1.12 Although no two look alike, these kittens have inherited genes from both parents and share many of the same characteristics. (credit: Rocky Mountain Feline Rescue)

Regulation

Even the smallest organisms are complex and require multiple regulatory mechanisms to coordinate internal functions, respond to stimuli, and cope with environmental stresses. Two examples of internal functions regulated in an organism are nutrient transport and blood flow. Organs (groups of tissues working together) perform specific functions, such as carrying oxygen throughout the body, removing wastes, delivering nutrients to every cell, and cooling the body.

Homeostasis

Figure 1.13 Polar bears (Ursus maritimus) and other mammals living in ice-covered regions maintain their body temperature by generating heat and reducing heat loss through thick fur and a dense layer of fat under their skin. (credit: “longhorndave”/Flickr)

In order to function properly, cells need to have appropriate conditions such as proper temperature, pH, and appropriate concentration of diverse chemicals. These conditions may, however, change from one moment to the next. Organisms are able to maintain internal conditions within a narrow range almost constantly, despite environmental changes, through homeostasis (literally, “steady state”)—the ability of an organism to maintain constant internal conditions. For example, an organism needs to regulate body temperature through a process known as thermoregulation. Organisms that live in cold climates, such as the polar bear (Figure 1.13), have body structures that help them withstand low temperatures and conserve body heat. Structures that aid in this type of insulation include fur, feathers, blubber, and fat. In hot climates, organisms have methods (such as perspiration in humans or panting in dogs) that help them to shed excess body heat.

Energy Processing

Figure 1.14 The California condor (Gymnogyps californianus) uses chemical energy derived from food to power flight. California condors are an endangered species; this bird has a wing tag that helps biologists identify the individual. (credit: Pacific Southwest Region U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

All organisms use a source of energy for their metabolic activities. Some organisms capture energy from the sun and convert it into chemical energy in food; others use chemical energy in molecules they take in as food (Figure 1.14).

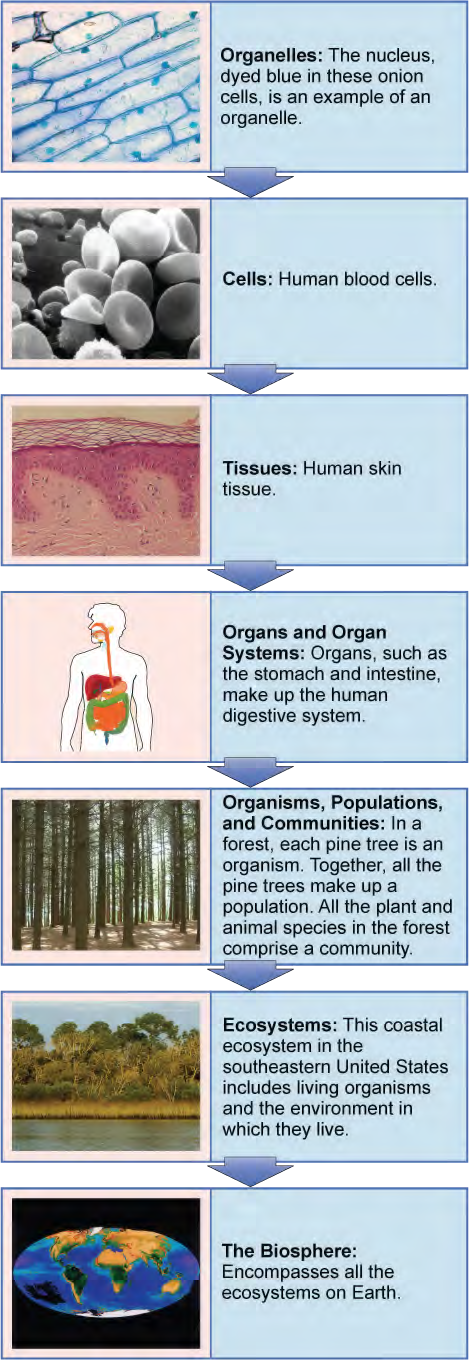

Levels of Organization of Living Things

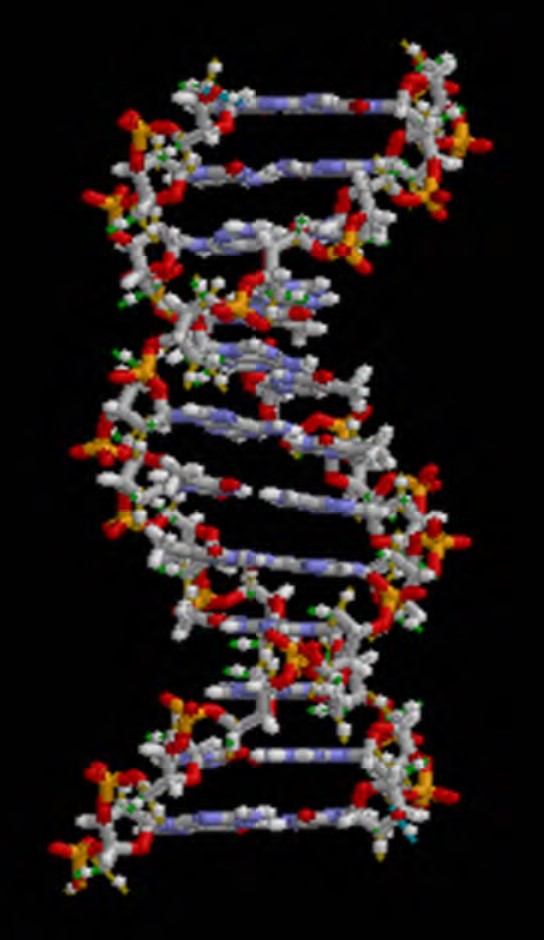

Living things are highly organized and structured, following a hierarchy that can be examined on a scale from small to large. The atom is the smallest and most fundamental unit of matter. It consists of a nucleus surrounded by electrons. Atoms form molecules. A molecule is a chemical structure consisting of at least two atoms held together by one or more chemical bonds. Many molecules that are biologically important are macromolecules, large molecules that are typically formed by polymerization (a polymer is a large molecule that is made by combining smaller units called monomers, which are simpler than macromolecules). An example of a macromolecule is deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) (Figure 1.15), which contains the instructions for the structure and functioning of all living organisms.

Figure 1.15 All molecules, including this DNA molecule, are composed of atoms. (credit: “brian0918”/Wikimedia Commons)

Watch this video (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/rotating_DNA) that animates the three-dimensional structure of the DNA molecule shown in Figure 1.15.

Some cells contain aggregates of macromolecules surrounded by membranes; these are called organelles. Organelles are small structures that exist within cells. Examples of organelles include mitochondria and chloroplasts, which carry out indispensable functions: mitochondria produce energy to power the cell, while chloroplasts enable green plants to utilize the energy in sunlight to make sugars. All living things are made of cells; the cell itself is the smallest fundamental unit of structure and function in living organisms. (This requirement is why viruses are not considered living: they are not made of cells. To make new viruses, they have to invade and hijack the reproductive mechanism of a living cell; only then can they obtain the materials they need to reproduce.) Some organisms consist of a single cell and others are multicellular. Cells are classified as prokaryotic or eukaryotic. Prokaryotes are single-celled or colonial organisms that do not have membrane-bound nuclei; in contrast, the cells of eukaryotes do have membrane-bound organelles and a membrane-bound nucleus.

In larger organisms, cells combine to make tissues, which are groups of similar cells carrying out similar or related functions. Organs are collections of tissues grouped together performing a common function. Organs are present not only in animals but also in plants. An organ system is a higher level of organization that consists of functionally related organs. Mammals have many organ systems. For instance, the circulatory system transports blood through the body and to and from the lungs; it includes organs such as the heart and blood vessels. Organisms are individual living entities. For example, each tree in a forest is an organism. Single-celled prokaryotes and single-celled eukaryotes are also considered organisms and are typically referred to as microorganisms.

All the individuals of a species living within a specific area are collectively called a population. For example, a forest may include many pine trees. All of these pine trees represent the population of pine trees in this forest. Different populations may live in the same specific area. For example, the forest with the pine trees includes populations of flowering plants and also insects and microbial populations. A community is the sum of populations inhabiting a particular area. For instance, all of the trees, flowers, insects, and other populations in a forest form the forest’s community. The forest itself is an ecosystem. An ecosystem consists of all the living things in a particular area together with the abiotic, non-living parts of that environment such as nitrogen in the soil or rain water. At the highest level of organization (Figure 1.16), the biosphere is the collection of all ecosystems, and it represents the zones of life on earth. It includes land, water, and even the atmosphere to a certain extent.

Figure 1.16The biological levels of organization of living things are shown. From a singleorganelle to the entire biosphere, living organisms are parts of a highly structured hierarchy.(credit “organelles”: modification of work by Umberto Salvagnin; credit “cells”: modification ofwork by Bruce Wetzel, Harry Schaefer/ National Cancer Institute; credit “tissues”: modificationof work by Kilbad; Fama Clamosa; Mikael Häggström; credit “organs”: modification of workby Mariana Ruiz Villareal; credit “organisms”: modification of work by “Crystal”/Flickr; credit“ecosystems”: modification of work by US Fish and Wildlife Service Headquarters; credit“biosphere”: modification of work by NASA)Which of the following statements is false?a.Tissues exist within organs which exist within organ systems.

Figure 1.16The biological levels of organization of living things are shown. From a singleorganelle to the entire biosphere, living organisms are parts of a highly structured hierarchy.(credit “organelles”: modification of work by Umberto Salvagnin; credit “cells”: modification ofwork by Bruce Wetzel, Harry Schaefer/ National Cancer Institute; credit “tissues”: modificationof work by Kilbad; Fama Clamosa; Mikael Häggström; credit “organs”: modification of workby Mariana Ruiz Villareal; credit “organisms”: modification of work by “Crystal”/Flickr; credit“ecosystems”: modification of work by US Fish and Wildlife Service Headquarters; credit“biosphere”: modification of work by NASA)Which of the following statements is false?a.Tissues exist within organs which exist within organ systems.

|

b. |

Communities exist within populations which exist within ecosystems. |

|

c. |

Organelles exist within cells which exist within tissues. |

|

d. |

Communities exist within ecosystems which exist in the biosphere. |

|

|

|

The Diversity of Life

The fact that biology, as a science, has such a broad scope has to do with the tremendous diversity of life on earth. The source of this diversity is evolution, the process of gradual change during which new species arise from older species. Evolutionary biologists study the evolution of living things in everything from the microscopic world to ecosystems.

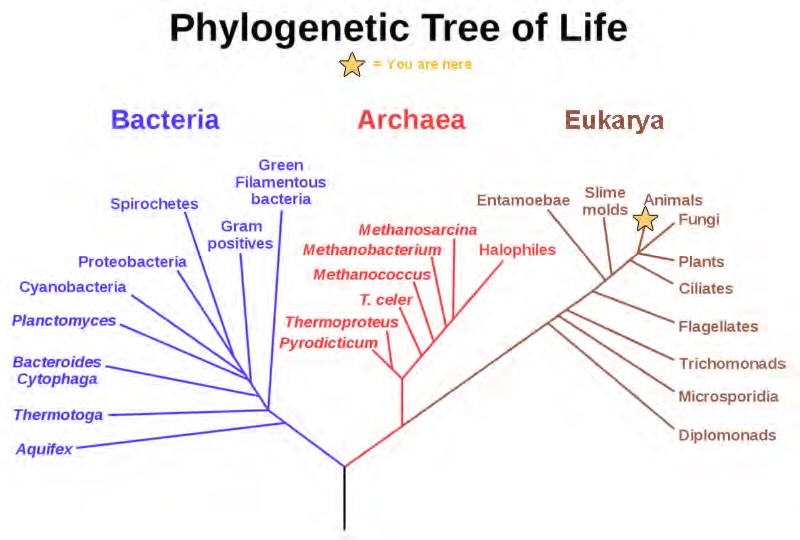

The evolution of various life forms on Earth can be summarized in a phylogenetic tree (Figure 1.17). A phylogenetic tree is a diagram showing the evolutionary relationships among biological species based on similarities and differences in genetic or physical traits or both. A phylogenetic tree is composed of nodes and branches. The internal nodes represent ancestors and are points in evolution when, based on scientific evidence, an ancestor is thought to have diverged to form two new species. The length of each branch is proportional to the time elapsed since the split.

Figure 1.17 This phylogenetic tree was constructed by microbiologist Carl Woese using data obtained from sequencing ribosomal RNA genes. The tree shows the separation of living organisms into three domains: Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya. Bacteria and Archaea are prokaryotes, singlecelled organisms lacking intracellular organelles. (credit: Eric Gaba; NASA Astrobiology Institute)

Branches of Biological Study

The scope of biology is broad and therefore contains many branches and subdisciplines. Biologists may pursue one of those subdisciplines and work in a more focused field. For instance, molecular biology and biochemistry study biological processes at the molecular and chemical level, including interactions among molecules such as DNA, RNA, and proteins, as well as the way they are regulated. Microbiology, the study of microorganisms, is the study of the structure and function of single-celled organisms. It is quite a broad branch itself, and depending on the subject of study, there are also microbial physiologists, ecologists, and geneticists, among others.

Another field of biological study, neurobiology, studies the biology of the nervous system, and although it is considered a branch of biology, it is also recognized as an interdisciplinary field of study known as neuroscience. Because of its interdisciplinary nature, this subdiscipline studies different functions of the nervous system using molecular, cellular, developmental, medical, and computational approaches.

Figure 1.20 Researchers work on excavating dinosaur fossils at a site in Castellón, Spain. (credit: Mario Modesto)

Paleontology, another branch of biology, uses fossils to study life’s history (Figure 1.20). Zoology and botany are the study of animals and plants, respectively. Biologists can also specialize as biotechnologists, ecologists, or physiologists, to name just a few areas. This is just a small sample of the many fields that biologists can pursue.

Biology is the culmination of the achievements of the natural sciences from their inception to today. Excitingly, it is the cradle of emerging sciences, such as the biology of brain activity, genetic engineering of custom organisms, and the biology of evolution that uses the laboratory tools of molecular biology to retrace the earliest stages of life on earth. A scan of news headlines—whether reporting on immunizations, a newly discovered species, sports doping, or a genetically-modified food—demonstrates the way biology is active in and important to our everyday world.

KEY TERMS

abstract opening section of a scientific paper that summarizes the research and conclusions applied science form of science that aims to solve real-world problems atom smallest and most fundamental unit of matter

basic science science that seeks to expand knowledge and understanding regardless of the shortterm application of that knowledge biochemistry study of the chemistry of biological organisms biology the study of living organisms and their interactions with one another and their environments biosphere collection of all the ecosystems on Earth botany study of plants

cell smallest fundamental unit of structure and function in living things community set of populations inhabiting a particular area

conclusion section of a scientific paper that summarizes the importance of the experimental findings control part of an experiment that does not change during the experiment

deductive reasoning form of logical thinking that uses a general inclusive statement to forecast specific results

descriptive science (also, discovery science) form of science that aims to observe, explore, and investigate

discussion section of a scientific paper in which the author interprets experimental results, describes how variables may be related, and attempts to explain the phenomenon in question

ecosystem all the living things in a particular area together with the abiotic, nonliving parts of that environment eukaryote organism with cells that have nuclei and membrane-bound organelles

evolution process of gradual change during which new species arise from older species and some species become extinct falsifiable able to be disproven by experimental results homeostasis ability of an organism to maintain constant internal conditions

hypothesis-based science form of science that begins with a specific question and potential testable answers hypothesis suggested explanation for an observation, which can be tested

inductive reasoning form of logical thinking that uses related observations to arrive at a general conclusion

introduction opening section of a scientific paper, which provides background information about what was known in the field prior to the research reported in the paper life science field of science, such as biology, that studies living things macromolecule large molecule, typically formed by the joining of smaller molecules

materials and methods section of a scientific paper that includes a complete description of the substances, methods, and techniques used by the researchers to gather data

microbiology study of the structure and function of microorganisms

molecular biology study of biological processes and their regulation at the molecular level, including interactions among molecules such as DNA, RNA, and proteins

molecule chemical structure consisting of at least two atoms held together by one or more chemical bonds

natural science field of science that is related to the physical world and its phenomena and processes neurobiology study of the biology of the nervous system organ system level of organization that consists of functionally related interacting organs organelle small structures that exist within cells and carry out cellular functions organism individual living entity organ collection of related tissues grouped together performing a common function paleontology study of life’s history by means of fossils

peer-reviewed manuscript scientific paper that is reviewed by a scientist’s colleagues who are experts in the field of study

phylogenetic tree diagram showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological species based on similarities and differences in genetic or physical traits or both; in essence, a hypothesis concerning evolutionary connections

physical science field of science, such as geology, astronomy, physics, and chemistry, that studies nonliving matter

plagiarism using other people’s work or ideas without proper citation, creating the false impression that those are the author’s original ideas population all of the individuals of a species living within a specific area

prokaryote single-celled organism that lacks organelles and does not have nuclei surrounded by a nuclear membrane

results section of a scientific paper in which the author narrates the experimental findings and presents relevant figures, pictures, diagrams, graphs, and tables, without any further interpretation

review article paper that summarizes and comments on findings that were published as primary

literature

science knowledge that covers general truths or the operation of general laws, especially when acquired and tested by the scientific method

scientific method method of research with defined steps that include observation, formulation of a hypothesis, testing, and confirming or falsifying the hypothesis serendipity fortunate accident or a lucky surprise theory tested and confirmed explanation for observations or phenomena tissue group of similar cells carrying out related functions variable part of an experiment that the experimenter can vary or change zoology study of animals

CHAPTER SUMMARY

1.1 The Science of Biology

Biology is the science that studies living organisms and their interactions with one another and their environments. Science attempts to describe and understand the nature of the universe in whole or in part by rational means. Science has many fields; those fields related to the physical world and its phenomena are considered natural sciences.

Science can be basic or applied. The main goal of basic science is to expand knowledge without any expectation of short-term practical application of that knowledge. The primary goal of applied research, however, is to solve practical problems.

Two types of logical reasoning are used in science. Inductive reasoning uses particular results to produce general scientific principles. Deductive reasoning is a form of logical thinking that predicts results by applying general principles. The common thread throughout scientific research is the use of the scientific method, a step-based process that consists of making observations, defining a problem, posing hypotheses, testing these hypotheses, and drawing one or more conclusions. The testing uses proper controls. Scientists present their results in peer-reviewed scientific papers published in scientific journals. A scientific research paper consists of several well-defined sections: introduction, materials and methods, results, and, finally, a concluding discussion. Review papers summarize the research done in a particular field over a period of time.

1.2 Themes and Concepts of Biology

Biology is the science of life. All living organisms share several key properties such as order, sensitivity or response to stimuli, reproduction, growth and development, regulation, homeostasis, and energy processing. Living things are highly organized parts of a hierarchy that includes atoms, molecules, organelles, cells, tissues, organs, and organ systems. Organisms, in turn, are grouped as populations, communities, ecosystems, and the biosphere. The great diversity of life today evolved from less-diverse ancestral organisms over billions of years. A diagram called a phylogenetic tree can be used to show evolutionary relationships among organisms.

Biology is very broad and includes many branches and subdisciplines. Examples include molecular biology, microbiology, neurobiology, zoology, and botany, among others.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

- The first forms of life on Earth were ________.

- plants

- microorganisms

- birds

- dinosaurs

- A suggested and testable explanation for an event is called a ________.

- hypothesis

- variable

- theory

- control

- Which of the following sciences is not considered a natural science?

- biology

- astronomy

- physics

- computer science

- The type of logical thinking that uses related observations to arrive at a general conclusion is called ________.

- deductive reasoning

- the scientific method

- hypothesis-based science

- inductive reasoning

- The process of ________ helps to ensure that a scientist’s research is original, significant, logical, and thorough.

- publication

- public speaking

- peer review

- the scientific method

- A person notices that her houseplants that are regularly exposed to music seem to grow more quickly than those in rooms with no music. As a result, she determines that plants grow better when exposed to music. This example most closely resembles which type of reasoning?

- inductive reasoning

- deductive reasoning

- neither, because no hypothesis was made

- both inductive and deductive reasoning

- The smallest unit of biological structure that meets the functional requirements of “living” is the ________.

- organ

- organelle

- cell

- macromolecule

- Viruses are not considered living because they ________.

- are not made of cells

- lack cell nuclei

- do not contain DNA or RNA

- cannot reproduce

- The presence of a membrane-enclosed nucleus is a characteristic of ________.

- prokaryotic cells

- eukaryotic cells

- living organisms

- bacteria

- A group of individuals of the same species living in the same area is called a(n) ________.

- family

- community

- population

- ecosystem

Which of the following sequences represents the hierarchy of biological organization from the most inclusive to the least complex level?

- organelle, tissue, biosphere, ecosystem, population

- organism, organ, tissue, organelle, molecule

- organism, community, biosphere, molecule, tissue, organ

- biosphere, ecosystem, community, population, organism

Where in a phylogenetic tree would you expect to find the organism that had evolved most recently?

- at the base

- within the branches

- at the nodes

- at the branch tip

Academic Skill: Focus on Lecture

As a reminder, here are the types of lectures you might be listening to in this section.

Hand-in-Hand lectures: These lectures are right over the material in the books.

Jumping off Point lectures: these lectures “jump off” from the book material. They bring in materials you cannot read about in the book—they may expand on ideas in the book or provide examples of concepts in the book.

Combination lectures: These lectures combine both Hand-in-hand and Jumping off point lectures.

Use these strategies now to warm-up, work out, and cool down as you listen to the lectures in about Biology.

|

|

Activity |

|

Warm-up |

To warm up your brain before a lecture, look over the notes you took in while reading the chapter. Based on the title of the lecture, what do you think it will be about? How does the lecture relate to the textbook chapter that you just finished reading? |

|

Work out |

Take notes on the lecture. Review the strategies for taking notes.

|

|

Cool Down |

To cool down in lectures means to review your notes within 24 hours of taking them. Information from lectures is easy to forget, so the sooner you review them, the better. |

Warming up for Notetaking

- Make sure you have the right materials before you begin to listen to the lectures. This might include a pen or pencil, notepaper and a highlighter or two.

- Date your notes.

- Label your notes. You have several lectures to listen to, so make sure each section of your notes contain the title of each lecture.

Working out During Notetaking

Choose a method for taking notes on the lecture and make sure that the method you choose…

- allows you to clearly record main ideas from a lecture

- Is “sustainable.” It is impossible to write down every word your instructor says. Therefore, you need to develop a method of taking notes that allows you to record a great deal of information quickly—this may involve developing a series of abbreviations,

- using symbols or creating an outline. Note taking strategies that require you to write out full sentences, spell all words correctly and record every idea are not sustainable because you will quickly fall behind.

- produces reviewable notes. The notes you take during a lecture are supposed to be like a second textbook for your class. They are useless if you cannot use them to study for exams or do other assignments for the class. Your notes need to be legible, and have enough information that, when you go back, you can make sense of what you wrote.

Don’t forget the tips as you take notes on the lectures:

- Abbreviate

- Listen for Phrases that Help You Set Goals

Take notes on the following lectures.

You can also copy and paste the URL into a browser.

David Deutsch: A New Way to Explain

https://www.ted.com/talks/david_deutsch_a_new_way_to_explain_explanation

Jonathan Drori: The Beautiful Tricks of Flowers

https://www.ted.com/talks/jonathan_drori_the_beautiful_tricks_of_flowers

Drew Berry: Animations of Unseeable Biology

https://www.ted.com/talks/drew_berry_animations_of_unseeable_biology

David Bolinsky: Animates a Cell

https://www.ted.com/talks/david_bolinsky_animates_a_cell

Cooling Down After the Lecture

After taking notes, you are going to want to organize them.

- Create an “index.” After the lecture is over, jot down a few words about the subject of that day’s notes. Put it under the date that you put across the top of the page.

- Use a highlighter to mark important terms.

- Use a different colored pen and/or highlighters to go back to your notes and make your own headings and subheadings.

- Tab your notes.

Having well-organized notes is a great start, but it isn’t quite enough. After you organize your notes, you need to review them. Here are some ways to review your notes:

What type of lecture is it? Hand-in-Hand or Jumping-off-point? How does the lecture relate to the textbook chapter?

Make sure you understood the lecture itself. When you review, pretend you need to tell a classmate who missed the lecture what the main ideas were. Actually explain the notes—either out loud or silently.

Add additional notes of explanation you didn’t get a chance to add in class. Make sure you understand any abbreviations you might have used.

Identify concepts that were not clear to you. Mark confusing parts up with questions marks and find a classmate, a tutor, or your instructor to get the concepts clarified.

Share notes with a classmate. What did he or she write down? How is it different from what you wrote down? What can you add to one another’s notes?

Academic Skill 2: Focus on Writing

Much of the writing you will do for college classes will be Academic Essays—and they can be very different from one another.

A good college writer warms up, works out, then cools down. Here is how that process applies to writing college-level papers:

|

|

Activity |

|

Warm-up |

To warm up your brain, carefully read the prompt you were given for your paper. ( A prompt is the assignment your instructor gives you that tells you what your paper should be about). Think about these questions: What information should be in my introduction? What information should be in the body of my paper? How will I end my paper? Take a few notes about what you think you should do and then re-read the prompt. Do your ideas still seem to make sense?

|

|

Work out |

To work out in writing, you need to write your paper! This will involve selecting strategies that will help you make your point most efficiently.

|

|

Cool Down |

To cool down in writing re-read what you have written and re-read the prompt. Make sure your writing choices still fit the prompt. Ask yourself “If a stranger were to read my paper over my shoulder, would it make sense?”

|

Here is your writing prompt. Choose one of the following to write an academic essay.

- Although the scientific method is used by most of the sciences, it can also be applied to everyday situations. Think about a problem that you may have at home, at school, or with your car, and apply the scientific method to solve it. Give an example of how applied science has had a direct effect on your daily life.

- Consider the levels of organization of the biological world, and place each of these items in order from smallest level of organization to most encompassing: skin cell, elephant, water molecule, planet Earth, tropical rainforest, hydrogen atom, wolf pack, liver.

- You go for a long walk on a hot day. Describe the way in which homeostasis keeps your body healthy.

- Using examples, explain how biology can be studied from a microscopic approach to a global approach.

How will you approach this essay assignment? Review the following structure for an academic essay.

Structure for an Academic Essay

|

Introduction Your introductory paragraph will have two main parts. |

Part 1: Establishing Authority- When you establish authority, you are doing two things—1) convincing your readers that you are expert enough on the topic to be worth listening to and 2) providing them with the information they need to understand your paper. The Establishing authority part of your paper begins with the very first sentence and ends just before the thesis.

|

|

Part 2: Thesis- The thesis statement is a sentence that tells the reader what you will prove in the paper. In shorter essays, the thesis sentence is always the last sentence of the introductory paragraph—just after the establishing authority.

|

|

|

Body Paragraphs Each body paragraph will have three parts. |

Part 1: Topic Sentence- in most academic essays, the topic sentence is the very first sentence of the paragraph and it plays an important role. It makes a claim that the rest of the paragraph will prove or support.

|

|

Part 2: Evidence– in an academic essay, the evidence section is the middle of the paragraph and longest part of the paragraph. Here is where you will actually work to convince your reader that the claim you made in your topic sentence is true. |

|

|

Part 3: Evaluation– In the academic essay, the evaluation usually comes at the end of the paragraph and it helps the reader understand why the evidence is should be taken seriously.

|

|

|

Conclusion Your conclusion will have two parts. |

Conclusions sum up what you have already said. New information should not appear in a conclusion, although you may wish to leave your reader with something interesting to think about. Part 1: Restate the thesis– Here, all you need to do is go back to the thesis statement that is at the end of the first paragraph you wrote and state it again in your last paragraph with slightly different words.

|

|

Part 2: Sum up main points– In this part of the conclusion, you just need to go back to each body paragraph and sum up its main point.

|

|

Warm up for Writing

Remember to…

Make sure to carefully read the prompt you have chosen to write about.

What are your goals?

Do you know how it will be graded?

Working Out while Writing a Paper

Select the strategies that are most likely to help you achieve your goal.

|

Strategies for Establishing Authority Remember, the goal of establishing authority is to provide the reader with the information they need to understand your paper and prove to them that you are worth listening to. The following strategies will help you do that. |

|

|

Summary |

If you are responding to an essay, a video, a lecture or a book, you might choose to summarize its main ideas. This will help your reader understand the source you are responding to and prove that you are an expert—if you read a source and can summarize it, then you are an expert.

|

|

Narrative or short personal story |

If you are writing an essay that relates in some way to your life or the life or someone you know, you might choose to tell a personal story to establish authority. Doing so will prove to your reader that, because you have lived this, you are an expert.

|

|

Facts and History |

Sometimes statistics, percentages, dates or a brief historical overview are the best way to help your reader not only understand the issue you are writing about, but to show them you know your stuff.

|

|

Definition |

If you are writing about something your reader might not understand, define it so he or she will be able to understand your paper. When you are able to define a word or concept for your reader, they will see you as an expert.

|

|

Description |

If you are writing an essay that relates to your personal life, you may choose to describe something significant to your life such as an object or an emotion.

|

|

Strategies for Presenting Evidence Remember, the goal of presenting evidence is to provide the reader with the information they need to agree with the claims you are making in your paper. Evidence proves to the reader that what you are saying is true. The following strategies will help you do that. Note that many of the strategies are the same ones you can use to establish authority. |

|

|

Summary |

If you would like to use the ideas in an essay, a video, a lecture or a book to help you prove your point, you will need to summarize its main ideas in the evidence part of your body paragraphs. This will help your reader understand the source you are responding to and prove that you are an expert—if you read a source and can summarize it, then you are an expert.

|

|

Narrative or short personal story |

If you are writing an essay that relates in some way to your life or the life or someone you know, you might choose to tell a personal story for your evidence. Doing so will prove to your reader that, because you have lived this, you are an expert.

|

|

Facts and History |

Sometimes using statistics, percentages, dates or a brief historical overview are the best evidence you can give your reader to help him/her see that your viewpoint is worth considering.

|

|

Definition |

If you are writing about something your reader might not understand, define it so he or she will be able to understand your paper. When you are able to define a word or concept for your reader, your evidence will make much more sense.

|

|

Description |

If you are writing an essay that relates to your personal life, you may choose to describe something significant to your life such as an object or an emotion.

|

|

Quotes from Experts |

Sometimes the words of an expert is the best way for you to prove your point. Using quotes from sources is a great way to prove your point.

|

|

Compare/ Contrast |

In the evidence part of your body paragraphs, you might choose to compare/ contrast two or more things, people, places, concepts or events in order to make your point.

|

|

Strategies for Evaluating Your Paragraph Remember, the goal of the evaluation part of a paragraph is to explain to your reader why or how the evidence you presented proves the topic sentence you wrote. The following strategies will make it clear to your reader what exactly your evidence proves. In shorter academic essays, the evaluation is the last 2-4 sentences in a body paragraph. |

|

|

Why is this evidence important?

|

Explain why a person, concept, event, etc. is important. What will people be able to do or understand as a result of knowing the information you just presented?

|

|

How is the information presented in the evidence part of the paragraph related? |

Sometimes readers don’t understand the purpose of your paragraph unless you tell them directly. If your goal is to explain how two things are connected, similar or different, you will need to point that out at the end of your paragraph.

|

|

How did the information presented in the evidence in the evidence part of the paragraph affect me or someone else?

|

Explain how a person, event, idea, etc. affected a person, a group of people or a series of events. Sometimes, it isn’t clear to a reader how something affected you (if you are writing a personal essay) or someone or something else until you explain it.

|

|

What did I learn as a result of the evidence presented? How did I change?

|

Explain what you or someone else learned or how you or someone else changed as a result of an experience.

|

Cooling down After Writing a Paper

After you write your paper, re-read it carefully. To do this, go back to the “Structure of an Academic Essay” graphic and go through your paper section by section.

Do you establish authority?

Do you have a thesis statement where it belongs?

Do you have a topic sentence for each body paragraph?

Do you present evidence and write an evaluation for each paragraph?

Finally, re-read the prompt. Make sure your paper meets the instructor’s expectations.