2 Chapter 2: Stress

Academic Skill: Reading

This chapter features a chapter, lecture and a reading on Stress— this chapter will enable you to practice all the academic skills you have been learning in this book. As you read this chapter, consider that you have two major tasks you need to do once it is complete.

- You will be preparing for a discussion.

- You will need to prepare for a multiple-choice test on the material in the chapter.

- Write a paper in which you compare and contrast how the chapter discusses stress with the way the lecture does.

Warm Up

Here are the steps you need to take to decide on a pre-reading strategy:

What do I already know about this topic?

What vocabulary am I going to need to know to understand this? You might find a list of vocabulary or you might skim it for the bold and/or italicized words.

What do the pictures, charts, and graphs tell me about this topic?

Turn the headings into questions. (You can answer these questions when you’re working out.)

Read the first paragraph and the last paragraph. What is the main idea?

Read the first paragraph of each section. Make a quick outline.

What will I need to do when I finish reading? (Take a quiz, write a summary, respond, etc)

You might also take note of when a quiz, summary, or test is due. How many pages will you have to read? How many sections will you have to read?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Working out while Reading

While you are reading, you can’t simply run your eyes over the words and expect to retain anything anymore than you can expect to sit quietly in the corner at a choir rehearsal and learn the songs. While you read, you need to have a way to interact with the material so you can remember it.

There are several strategies you can use to become better at working out while you’re reading. Primarily, you will be taking notes while you read which is often called annotating.

Video on Creating an Annotation System

You might read in order to answer the questions (from the headings) in your warm up.

You might stop after each section and make a few notes about how this section connects to the previous section. How does this support the main idea? Can you describe events in order?

You might make a timeline, a Venn diagram, a mind map, or a chart in order to take notes.

You can read about how to use visuals and graphic organizers to read actively online.

You might make connections to what you already know (from the warm up activity).

You can explore a variety of ways to take notes. You can read an article about The Best Note-Taking Methods online. You can choose the outline method, the Cornell method, the Boxing method, the charting method, or the mapping method.

Once you have completed your warm-up, now it is time to decide on a work-out. Again, you can select more than one strategy if you would like to do so. You can also select one strategy you use in part of the chapter, but you can change your mind and use a different one in other parts of the chapter if it makes more sense. As the structure and the goals of the chapter change, you might like to change your notetaking strategy, just like a coach would change a game plan if the other team did something unexpected.

Below, write down which strategies you think you are most likely to use as your read. Why did you select the strategies that you did? Do you think you might adapt them?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reading: Stress Introduction

(Bibliography for this chapter is located in Appendix A)

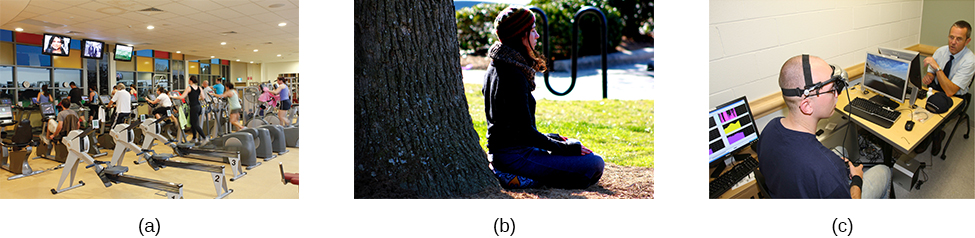

Exams are a stressful, but unavoidable, element of college life. (credit “left”: modification of work by Travis K. Mendoza; credit “center”: modification of work by “albertogp123”/Flickr; credit “right”: modification of work by Jeffrey Pioquinto, SJ)

Few would deny that today’s college students are under a lot of pressure. In addition to many usual stresses and strains incidental to the college experience (e.g., exams, term papers, and the dreaded freshman 15), students today are faced with increased college tuitions, burdensome debt, and difficulty finding employment after graduation. A significant population of non-traditional college students may face additional stressors, such as raising children or holding down a full-time job while working toward a degree.

Of course, life is filled with many additional challenges beyond those incurred in college or the workplace. We might have concerns with financial security, difficulties with friends or neighbors, family responsibilities, and we may not have enough time to do the things we want to do. Even minor hassles—losing things, traffic jams, and loss of internet service—all involve pressure and demands that can make life seem like a struggle and that can compromise our sense of well-being. That is, all can be stressful in some way.

Scientific interest in stress, including how we adapt and cope, has been longstanding in psychology; indeed, after nearly a century of research on the topic, much has been learned and many insights have been developed. This chapter examines stress and highlights our current understanding of the phenomenon, including its psychological and physiological natures, its causes and consequences, and the steps we can take to master stress rather than become its victim.

14.1 What Is Stress?

Page by: OpenStax

The term stress as it relates to the human condition first emerged in scientific literature in the 1930s, but it did not enter the popular vernacular until the 1970s (Lyon, 2012). Today, we often use the term loosely in describing a variety of unpleasant feeling states; for example, we often say we are stressed out when we feel frustrated, angry, conflicted, overwhelmed, or fatigued. Despite the widespread use of the term, stress is a fairly vague concept that is difficult to define with precision.

Researchers have had a difficult time agreeing on an acceptable definition of stress. Some have conceptualized stress as a demanding or threatening event or situation (e.g., a high-stress job, overcrowding, and long commutes to work). Such conceptualizations are known as stimulus-based definitions because they characterize stress as a stimulus that causes certain reactions. Stimulus-based definitions of stress are problematic, however, because they fail to recognize that people differ in how they view and react to challenging life events and situations. For example, a conscientious student who has studied diligently all semester would likely experience less stress during final exams week than would a less responsible, unprepared student.

Others have conceptualized stress in ways that emphasize the physiological responses that occur when faced with demanding or threatening situations (e.g., increased arousal). These conceptualizations are referred to as response-based definitions because they describe stress as a response to environmental conditions. For example, the endocrinologist Hans Selye, a famous stress researcher, once defined stress as the “response of the body to any demand, whether it is caused by, or results in, pleasant or unpleasant conditions” (Selye, 1976, p. 74). Selye’s definition of stress is response-based in that it conceptualizes stress chiefly in terms of the body’s physiological reaction to any demand that is placed on it. Neither stimulus-based nor response-based definitions provide a complete definition of stress. Many of the physiological reactions that occur when faced with demanding situations (e.g., accelerated heart rate) can also occur in response to things that most people would not consider to be genuinely stressful, such as receiving unanticipated good news: an unexpected promotion or raise.

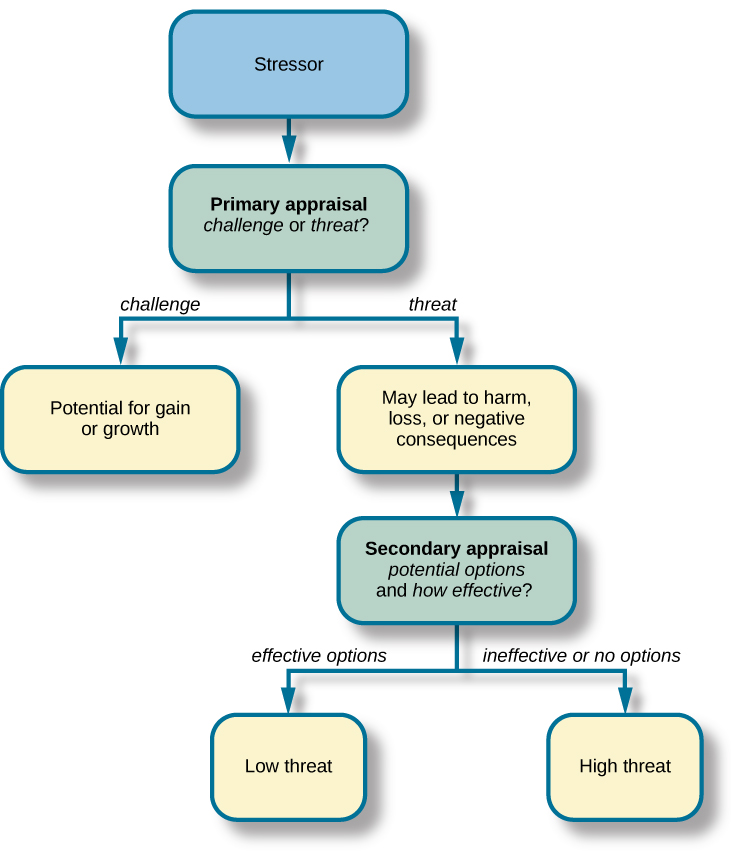

A useful way to conceptualize stress is to view it as a process whereby an individual perceives and responds to events that he appraises as overwhelming or threatening to his well-being (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). A critical element of this definition is that it emphasizes the importance of how we appraise—that is, judge—demanding or threatening events (often referred to as stressors); these appraisals, in turn, influence our reactions to such events. Two kinds of appraisals of a stressor are especially important in this regard: primary and secondary appraisals. A primary appraisal involves judgment about the degree of potential harm or threat to well-being that a stressor might entail. A stressor would likely be appraised as a threat if one anticipates that it could lead to some kind of harm, loss, or other negative consequence; conversely, a stressor would likely be appraised as a challenge if one believes that it carries the potential for gain or personal growth. For example, an employee who is promoted to a leadership position would likely perceive the promotion as a much greater threat if she believed the promotion would lead to excessive work demands than if she viewed it as an opportunity to gain new skills and grow professionally. Similarly, a college student on the cusp of graduation may face the change as a threat or a challenge (Figure).

Graduating from college and entering the workforce can be viewed as either a threat (loss of financial support) or a challenge (opportunity for independence and growth). (credit: Timothy Zanker)

The perception of a threat triggers a secondary appraisal: judgment of the options available to cope with a stressor, as well as perceptions of how effective such options will be (Lyon, 2012) (Figure). As you may recall from what you learned about self-efficacy, an individual’s belief in his ability to complete a task is important (Bandura, 1994). A threat tends to be viewed as less catastrophic if one believes something can be done about it (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Imagine that two middle-aged women, Robin and Maria, perform breast self-examinations one morning and each woman notices a lump on the lower region of her left breast. Although both women view the breast lump as a potential threat (primary appraisal), their secondary appraisals differ considerably. In considering the breast lump, some of the thoughts racing through Robin’s mind are, “Oh my God, I could have breast cancer! What if the cancer has spread to the rest of my body and I cannot recover? What if I have to go through chemotherapy? I’ve heard that experience is awful! What if I have to quit my job? My husband and I won’t have enough money to pay the mortgage. Oh, this is just horrible…I can’t deal with it!” On the other hand, Maria thinks, “Hmm, this may not be good. Although most times these things turn out to be benign, I need to have it checked out. If it turns out to be breast cancer, there are doctors who can take care of it because the medical technology today is quite advanced. I’ll have a lot of different options, and I’ll be just fine.” Clearly, Robin and Maria have different outlooks on what might turn out to be a very serious situation: Robin seems to think that little could be done about it, whereas Maria believes that, worst case scenario, a number of options that are likely to be effective would be available. As such, Robin would clearly experience greater stress than would Maria.

When encountering a stressor, a person judges its potential threat (primary appraisal) and then determines if effective options are available to manage the situation. Stress is likely to result if a stressor is perceived as extremely threatening or threatening with few or no effective coping options available.

To be sure, some stressors are inherently more stressful than others in that they are more threatening and leave less potential for variation in cognitive appraisals (e.g., objective threats to one’s health or safety). Nevertheless, appraisal will still play a role in augmenting or diminishing our reactions to such events (Everly & Lating, 2002).

If a person appraises an event as harmful and believes that the demands imposed by the event exceed the available resources to manage or adapt to it, the person will subjectively experience a state of stress. In contrast, if one does not appraise the same event as harmful or threatening, she is unlikely to experience stress. According to this definition, environmental events trigger stress reactions by the way they are interpreted and the meanings they are assigned. In short, stress is largely in the eye of the beholder: it’s not so much what happens to you as it is how you respond (Selye, 1976).

Good Stress?

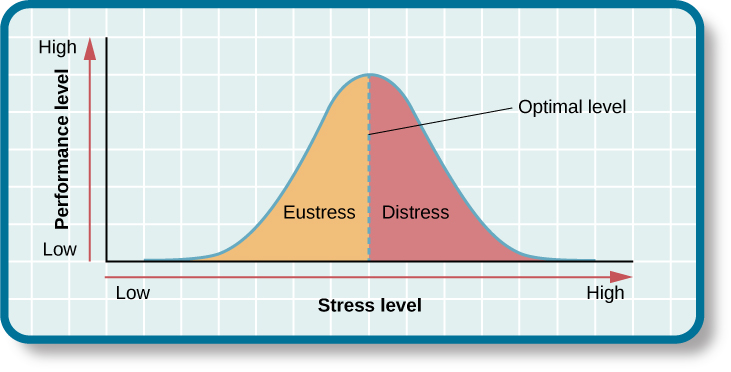

Although stress carries a negative connotation, at times it may be of some benefit. Stress can motivate us to do things in our best interests, such as study for exams, visit the doctor regularly, exercise, and perform to the best of our ability at work. Indeed, Selye (1974) pointed out that not all stress is harmful. He argued that stress can sometimes be a positive, motivating force that can improve the quality of our lives. This kind of stress, which Selye called eustress (from the Greek eu = “good”), is a good kind of stress associated with positive feelings, optimal health, and performance. A moderate amount of stress can be beneficial in challenging situations. For example, athletes may be motivated and energized by pregame stress, and students may experience similar beneficial stress before a major exam. Indeed, research shows that moderate stress can enhance both immediate and delayed recall of educational material. Male participants in one study who memorized a scientific text passage showed improved memory of the passage immediately after exposure to a mild stressor as well as one day following exposure to the stressor (Hupbach & Fieman, 2012).

Increasing one’s level of stress will cause performance to change in a predictable way. As shown in Figure, as stress increases, so do performance and general well-being (eustress); when stress levels reach an optimal level (the highest point of the curve), performance reaches its peak. A person at this stress level is colloquially at the top of his game, meaning he feels fully energized, focused, and can work with minimal effort and maximum efficiency. But when stress exceeds this optimal level, it is no longer a positive force—it becomes excessive and debilitating, or what Selye termed distress (from the Latin dis = “bad”). People who reach this level of stress feel burned out; they are fatigued, exhausted, and their performance begins to decline. If the stress remains excessive, health may begin to erode as well (Everly & Lating, 2002).

As the stress level increases from low to moderate, so does performance (eustress). At the optimal level (the peak of the curve), performance has reached its peak. If stress exceeds the optimal level, it will reach the distress region, where it will become excessive and debilitating, and performance will decline (Everly & Lating, 2002).

The Prevalence of Stress

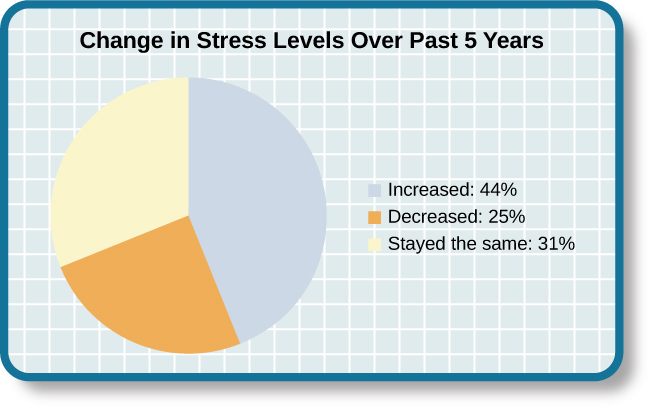

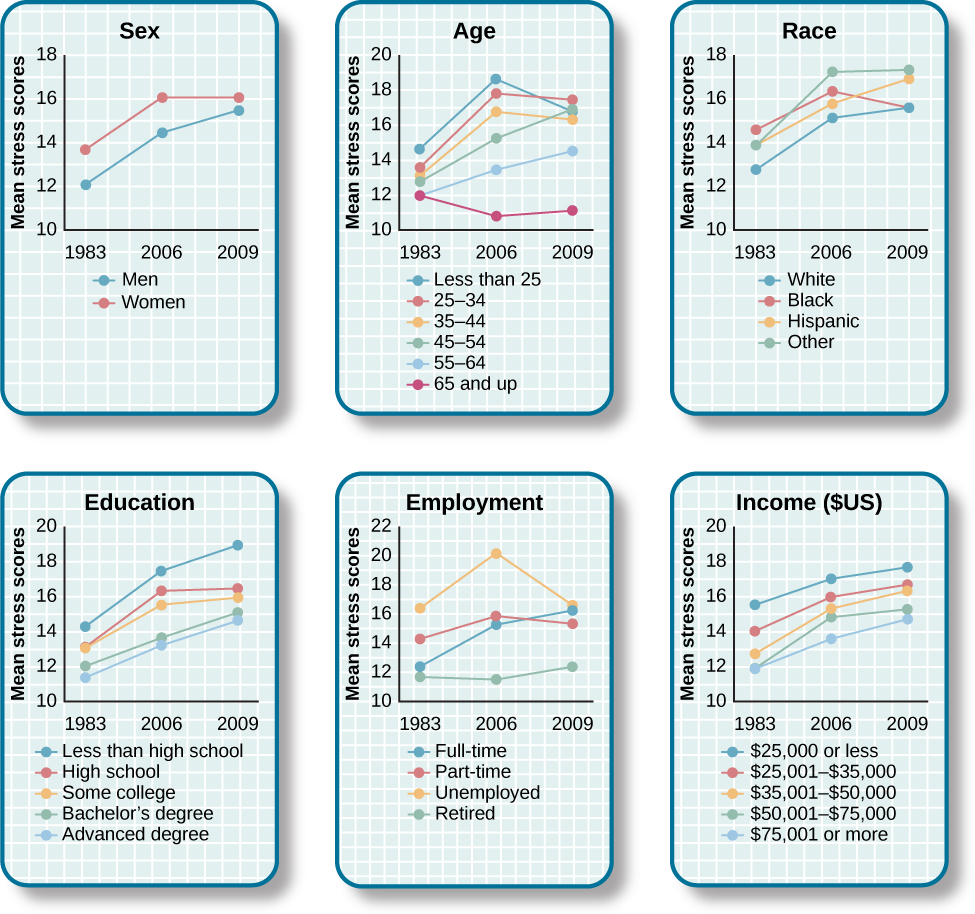

Stress is everywhere and, as shown in Figure, it has been on the rise over the last several years. Each of us is acquainted with stress—some are more familiar than others. In many ways, stress feels like a load you just can’t carry—a feeling you experience when, for example, you have to drive somewhere in a crippling blizzard, when you wake up late the morning of an important job interview, when you run out of money before the next pay period, and before taking an important exam for which you realize you are not fully prepared.

Nearly half of U.S. adults indicated that their stress levels have increased over the last five years (Neelakantan, 2013).

Stress is an experience that evokes a variety of responses, including those that are physiological (e.g., accelerated heart rate, headaches, or gastrointestinal problems), cognitive (e.g., difficulty concentrating or making decisions), and behavioral (e.g., drinking alcohol, smoking, or taking actions directed at eliminating the cause of the stress). Although stress can be positive at times, it can have deleterious health implications, contributing to the onset and progression of a variety of physical illnesses and diseases (Cohen & Herbert, 1996).

The scientific study of how stress and other psychological factors impact health falls within the realm of health psychology, a subfield of psychology devoted to understanding the importance of psychological influences on health, illness, and how people respond when they become ill (Taylor, 1999). Health psychology emerged as a discipline in the 1970s, a time during which there was increasing awareness of the role behavioral and lifestyle factors play in the development of illnesses and diseases (Straub, 2007). In addition to studying the connection between stress and illness, health psychologists investigate issues such as why people make certain lifestyle choices (e.g., smoking or eating unhealthy food despite knowing the potential adverse health implications of such behaviors). Health psychologists also design and investigate the effectiveness of interventions aimed at changing unhealthy behaviors. Perhaps one of the more fundamental tasks of health psychologists is to identify which groups of people are especially at risk for negative health outcomes, based on psychological or behavioral factors.

For example, measuring differences in stress levels among demographic groups and how these levels change over time can help identify populations who may have an increased risk for illness or disease.

Figure depicts the results of three national surveys in which several thousand individuals from different demographic groups completed a brief stress questionnaire; the surveys were administered in 1983, 2006, and 2009 (Cohen & Janicki-Deverts, 2012). All three surveys demonstrated higher stress in women than in men. Unemployed individuals reported high levels of stress in all three surveys, as did those with less education and income; retired persons reported the lowest stress levels. However, from 2006 to 2009 the greatest increase in stress levels occurred among men, Whites, people aged 45–64, college graduates, and those with full-time employment. One interpretation of these findings is that concerns surrounding the 2008–2009 economic downturn (e.g., threat of or actual job loss and substantial loss of retirement savings) may have been especially stressful to White, college-educated, employed men with limited time remaining in their working careers.

.

.

The charts above, adapted from Cohen & Janicki-Deverts (2012), depict the mean stress level scores among different demographic groups during the years 1983, 2006, and 2009. Across categories of sex, age, race, education level, employment status, and income, stress levels generally show a marked increase over this quarter-century time span.

Early Contributions to the Study of Stress

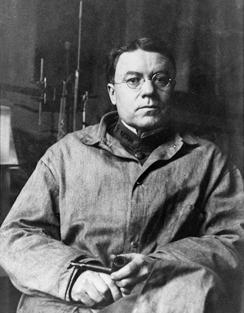

As previously stated, scientific interest in stress goes back nearly a century. One of the early pioneers in the study of stress was Walter Cannon, an eminent American physiologist at Harvard Medical School (Figure). In the early part of the 20th century, Cannon was the first to identify the body’s physiological reactions to stress.

Harvard physiologist Walter Cannon first articulated and named the fight-or-flight response, the nervous system’s sympathetic response to a significant stressor.

Cannon and the Fight-or-Flight Response

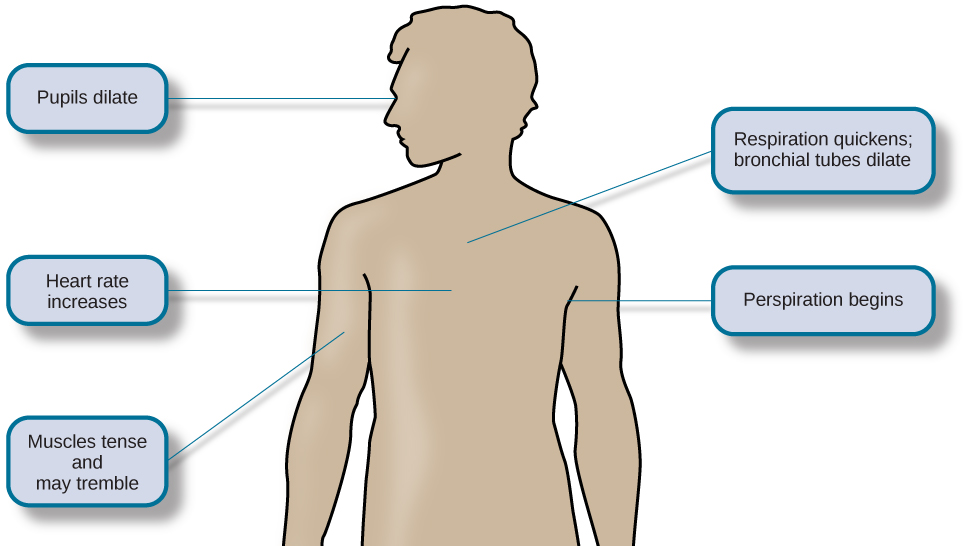

Imagine that you are hiking in the beautiful mountains of Colorado on a warm and sunny spring day. At one point during your hike, a large, frightening-looking black bear appears from behind a stand of trees and sits about 50 yards from you. The bear notices you, sits up, and begins to lumber in your direction. In addition to thinking, “This is definitely not good,” a constellation of physiological reactions begins to take place inside you. Prompted by a deluge of epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine (noradrenaline) from your adrenal glands, your pupils begin to dilate. Your heart starts to pound and speeds up, you begin to breathe heavily and perspire, you get butterflies in your stomach, and your muscles become tense, preparing you to take some kind of direct action. Cannon proposed that this reaction, which he called the fight-or-flight response, occurs when a person experiences very strong emotions—especially those associated with a perceived threat (Cannon, 1932). During the fight-or-flight response, the body is rapidly aroused by activation of both the sympathetic nervous system and the endocrine system (Figure). This arousal helps prepare the person to either fight or flee from a perceived threat.

Fight or flight is a physiological response to a stressor.

According to Cannon, the fight-or-flight response is a built-in mechanism that assists in maintaining homeostasis—an internal environment in which physiological variables such as blood pressure, respiration, digestion, and temperature are stabilized at levels optimal for survival. Thus, Cannon viewed the fight-or-flight response as adaptive because it enables us to adjust internally and externally to changes in our surroundings, which is helpful in species survival.

Selye and the General Adaptation Syndrome

Another important early contributor to the stress field was Hans Selye, mentioned earlier. He would eventually become one of the world’s foremost experts in the study of stress (Figure). As a young assistant in the biochemistry department at McGill University in the 1930s, Selye was engaged in research involving sex hormones in rats. Although he was unable to find an answer for what he was initially researching, he incidentally discovered that when exposed to prolonged negative stimulation (stressors)—such as extreme cold, surgical injury, excessive muscular exercise, and shock—the rats showed signs of adrenal enlargement, thymus and lymph node shrinkage, and stomach ulceration. Selye realized that these responses were triggered by a coordinated series of physiological reactions that unfold over time during continued exposure to a stressor. These physiological reactions were nonspecific, which means that regardless of the type of stressor, the same pattern of reactions would occur. What Selye discovered was the general adaptation syndrome, the body’s nonspecific physiological response to stress.

Hans Selye specialized in research about stress. In 2009, his native Hungary honored his work with this stamp, released in conjunction with the 2nd annual World Conference on Stress.

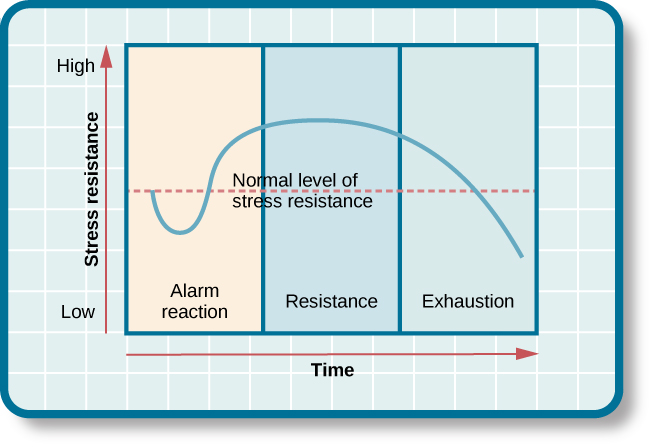

The general adaptation syndrome, shown in Figure, consists of three stages: (1) alarm reaction, (2) stage of resistance, and (3) stage of exhaustion (Selye, 1936; 1976). Alarm reaction describes the body’s immediate reaction upon facing a threatening situation or emergency, and it is roughly analogous to the fight-or-flight response described by Cannon. During an alarm reaction, you are alerted to a stressor, and your body alarms you with a cascade of physiological reactions that provide you with the energy to manage the situation. A person who wakes up in the middle of the night to discover her house is on fire, for example, is experiencing an alarm reaction.

The three stages of Selye’s general adaptation syndrome are shown in this graph. Prolonged stress ultimately results in exhaustion.

If exposure to a stressor is prolonged, the organism will enter the stage of resistance. During this stage, the initial shock of alarm reaction has worn off and the body has adapted to the stressor. Nevertheless, the body also remains on alert and is prepared to respond as it did during the alarm reaction, although with less intensity. For example, suppose a child who went missing is still missing 72 hours later. Although the parents would obviously remain extremely disturbed, the magnitude of physiological reactions would likely have diminished over the 72 intervening hours due to some adaptation to this event.

If exposure to a stressor continues over a longer period of time, the stage of exhaustion ensues. At this stage, the person is no longer able to adapt to the stressor: the body’s ability to resist becomes depleted as physical wear takes its toll on the body’s tissues and organs. As a result, illness, disease, and other permanent damage to the body—even death—may occur. If a missing child still remained missing after three months, the long-term stress associated with this situation may cause a parent to literally faint with exhaustion at some point or even to develop a serious and irreversible illness.

In short, Selye’s general adaptation syndrome suggests that stressors tax the body via a three-phase process—an initial jolt, subsequent readjustment, and a later depletion of all physicalresources—that ultimately lays the groundwork for serious health problems and even death. It should be pointed out, however, that this model is a response-based conceptualization of stress, focusing exclusively on the body’s physical responses while largely ignoring psychological factors such as appraisal and interpretation of threats. Nevertheless, Selye’s model has had an enormous impact on the field of stress because it offers a general explanation for how stress can lead to physical damage and, thus, disease. As we shall discuss later, prolonged or repeated stress has been implicated in development of a number of disorders such as hypertension and coronary artery disease.

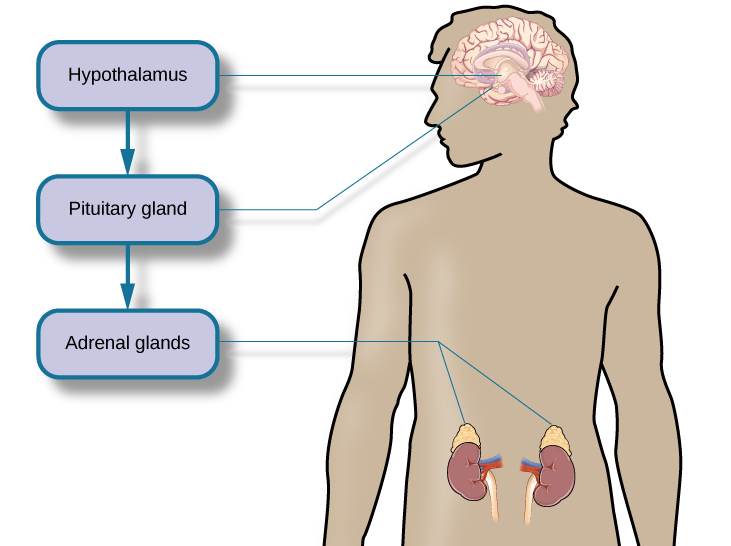

The Physiological Basis of Stress

What goes on inside our bodies when we experience stress? The physiological mechanisms of stress are extremely complex, but they generally involve the work of two systems—the sympathetic nervous system and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. When a person first perceives something as stressful (Selye’s alarm reaction), the sympathetic nervous system triggers arousal via the release of adrenaline from the adrenal glands. Release of these hormones activates the fight-or-flight responses to stress, such as accelerated heart rate and respiration. At the same time, the HPA axis, which is primarily endocrine in nature, becomes especially active, although it works much more slowly than the sympathetic nervous system. In response to stress, the hypothalamus (one of the limbic structures in the brain) releases corticotrophin-releasing factor, a hormone that causes the pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) (Figure). The ACTH then activates the adrenal glands to secrete a number of hormones into the bloodstream; an important one is cortisol, which can affect virtually every organ within the body. Cortisol is commonly known as a stress hormone and helps provide that boost of energy when we first encounter a stressor, preparing us to run away or fight. However, sustained elevated levels of cortisol weaken the immune system.

This diagram shows the functioning of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. The hypothalamus activates the pituitary gland, which in turn activates the adrenal glands, increasing their secretion of cortisol.

In short bursts, this process can have some favorable effects, such as providing extra energy, improving immune system functioning temporarily, and decreasing pain sensitivity. However, extended release of cortisol—as would happen with prolonged or chronic stress—often comes at a high price. High levels of cortisol have been shown to produce a number of harmful effects. For example, increases in cortisol can significantly weaken our immune system (Glaser & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2005), and high levels are frequently observed among depressed individuals (Geoffroy, Hertzman, Li, & Power, 2013). In summary, a stressful event causes a variety of physiological reactions that activate the adrenal glands, which in turn release epinephrine, norepinephrine, and cortisol. These hormones affect a number of bodily processes in ways that prepare the stressed person to take direct action, but also in ways that may heighten the potential for illness.

When stress is extreme or chronic, it can have profoundly negative consequences. For example, stress often contributes to the development of certain psychological disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder, major depressive disorder, and other serious psychiatric conditions. Additionally, we noted earlier that stress is linked to the development and progression of a variety of physical illnesses and diseases. For example, researchers in one study found that people injured during the September 11, 2001, World Trade Center disaster or who developed post-traumatic stress symptoms afterward later suffered significantly elevated rates of heart disease (Jordan, Miller-Archie, Cone, Morabia, & Stellman, 2011). Another investigation yielded that self-reported stress symptoms among aging and retired Finnish food industry workers were associated with morbidity 11 years later. This study also predicted the onset of musculoskeletal, nervous system, and endocrine and metabolic disorders (Salonen, Arola, Nygård, & Huhtala, 2008). Another study reported that male South Korean manufacturing employees who reported high levels of work-related stress were more likely to catch the common cold over the next several months than were those employees who reported lower work-related stress levels (Park et al., 2011). Later, you will explore the mechanisms through which stress can produce physical illness and disease.

Summary

Stress is a process whereby an individual perceives and responds to events appraised as overwhelming or threatening to one’s well-being. The scientific study of how stress and emotional factors impact health and well-being is called health psychology, a field devoted to studying the general impact of psychological factors on health. The body’s primary physiological response during stress, the fight-or-flight response, was first identified in the early 20th century by Walter Cannon. The fight-or-flight response involves the coordinated activity of both the sympathetic nervous system and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Hans Selye, a noted endocrinologist, referred to these physiological reactions to stress as part of general adaptation syndrome, which occurs in three stages: alarm reaction (fight-or-flight reactions begin), resistance (the body begins to adapt to continuing stress), and exhaustion (adaptive energy is depleted, and stress begins to take a physical toll).

Review Questions

Negative effects of stress are most likely to be experienced when an event is perceived as ________.

- negative, but it is likely to affect one’s friends rather than oneself

- challenging

- confusing

- threatening, and no clear options for dealing with it are apparent

Between 2006 and 2009, the greatest increases in stress levels were found to occur among ________.

- Black people

- those aged 45–64

- the unemployed

- those without college degrees

At which stage of Selye’s general adaptation syndrome is a person especially vulnerable to illness?

- exhaustion

- alarm reaction

- fight-or-flight

- resistance

During an encounter judged as stressful, cortisol is released by the ________.

- sympathetic nervous system

- hypothalamus

- pituitary gland

- adrenal glands

Critical Thinking Questions

Provide an example (other than the one described earlier) of a situation or event that could be appraised as either threatening or challenging.

Provide an example of a stressful situation that may cause a person to become seriously ill. How would Selye’s general adaptation syndrome explain this occurrence?

Personal Application Question

Think of a time in which you and others you know (family members, friends, and classmates) experienced an event that some viewed as threatening and others viewed as challenging. What were some of the differences in the reactions of those who experienced the event as threatening compared to those who viewed the event as challenging? Why do you think there were differences in how these individuals judged the same event?

Glossary

Alarm reaction- First stage of the general adaptation syndrome; characterized as the body’s immediate physiological reaction to a threatening situation or some other emergency; analogous to the fight-or-flight response

Cortisol-Stress hormone released by the adrenal glands when encountering a stressor; helps to provide a boost of energy, thereby preparing the individual to take action

Distress- Bad form of stress; usually high in intensity; often leads to exhaustion, fatigue, feeling burned out; associated with erosions in performance and health

Eustress- Good form of stress; low to moderate in intensity; associated with positive feelings, as well as optimal health and performance

fight-or-flight response- Set of physiological reactions (increases in blood pressure, heart rate, respiration rate, and sweat) that occur when an individual encounters a perceived threat; these reactions are produced by activation of the sympathetic nervous system and the endocrine system

General adaptation syndrome- Hans Selye’s three-stage model of the body’s physiological reactions to stress and the process of stress adaptation: alarm reaction, stage of resistance, and stage of exhaustion

Health psychology- Subfield of psychology devoted to studying psychological influences on health, illness, and how people respond when they become ill

Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis- Set of structures found in both the limbic system (hypothalamus) and the endocrine system (pituitary gland and adrenal glands) that regulate many of the body’s physiological reactions to stress through the release of hormones

Primary appraisal- Judgment about the degree of potential harm or threat to well-being that a stressor might entail

Secondary appraisal- Judgment of options available to cope with a stressor and their potential effectiveness

Stage of exhaustion- Third stage of the general adaptation syndrome; the body’s ability to resist stress becomes depleted; illness, disease, and even death may occur

Stage of resistance- Second stage of the general adaptation syndrome; the body adapts to a stressor for a period of time

Stress- Process whereby an individual perceives and responds to events that one appraises as overwhelming or threatening to one’s well-being

Stressors- Environmental events that may be judged as threatening or demanding; stimuli that initiate the stress process

14.2 Stressors

For an individual to experience stress, he must first encounter a potential stressor. In general, stressors can be placed into one of two broad categories: chronic and acute. Chronic stressors include events that persist over an extended period of time, such as caring for a parent with dementia, long-term unemployment, or imprisonment. Acute stressors involve brief focal events that sometimes continue to be experienced as overwhelming well after the event has ended, such as falling on an icy sidewalk and breaking your leg (Cohen, Janicki-Deverts, & Miller, 2007). Whether chronic or acute, potential stressors come in many shapes and sizes. They can include major traumatic events, significant life changes, daily hassles, as well as other situations in which a person is regularly exposed to threat, challenge, or danger.

Traumatic Events

Some stressors involve traumatic events or situations in which a person is exposed to actual or threatened death or serious injury. Stressors in this category include exposure to military combat, threatened or actual physical assaults (e.g., physical attacks, sexual assault, robbery, childhood abuse), terrorist attacks, natural disasters (e.g., earthquakes, floods, hurricanes), and automobile accidents. Men, non-Whites, and individuals in lower socioeconomic status (SES) groups report experiencing a greater number of traumatic events than do women, Whites, and individuals in higher SES groups (Hatch & Dohrenwend, 2007). Some individuals who are exposed to stressors of extreme magnitude develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): a chronic stress reaction characterized by experiences and behaviors that may include intrusive and painful memories of the stressor event, jumpiness, persistent negative emotional states, detachment from others, angry outbursts, and avoidance of reminders of the event (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013).

Life Changes

Most stressors that we encounter are not nearly as intense as the ones described above. Many potential stressors we face involve events or situations that require us to make changes in our ongoing lives and require time as we adjust to those changes. Examples include death of a close family member, marriage, divorce, and moving (Figure).

Some fairly typical life events, such as moving, can be significant stressors. Even when the move is intentional and positive, the amount of resulting change in daily life can cause stress. (credit: “Jellaluna”/Flickr)

In the 1960s, psychiatrists Thomas Holmes and Richard Rahe wanted to examine the link between life stressors and physical illness, based on the hypothesis that life events requiring significant changes in a person’s normal life routines are stressful, whether these events are desirable or undesirable. They developed the Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS), consisting of 43 life events that require varying degrees of personal readjustment (Holmes & Rahe, 1967). Many life events that most people would consider pleasant (e.g., holidays, retirement, marriage) are among those listed on the SRRS; these are examples of eustress. Holmes and Rahe also proposed that life events can add up over time, and that experiencing a cluster of stressful events increases one’s risk of developing physical illnesses.

In developing their scale, Holmes and Rahe asked 394 participants to provide a numerical estimate for each of the 43 items; each estimate corresponded to how much readjustment participants felt each event would require. These estimates resulted in mean value scores for each event—often called life change units (LCUs) (Rahe, McKeen, & Arthur, 1967). The numerical scores ranged from 11 to 100, representing the perceived magnitude of life change each event entails. Death of a spouse ranked highest on the scale with 100 LCUs, and divorce ranked second highest with 73 LCUs. In addition, personal injury or illness, marriage, and job termination also ranked highly on the scale with 53, 50, and 47 LCUs, respectively. Conversely, change in residence (20 LCUs), change in eating habits (15 LCUs), and vacation (13 LCUs) ranked low on the scale (Table). Minor violations of the law ranked the lowest with 11 LCUs. To complete the scale, participants checked yes for events experienced within the last 12 months. LCUs for each checked item are totaled for a score quantifying the amount of life change. Agreement on the amount of adjustment required by the various life events on the SRRS is highly consistent, even cross-culturally (Holmes & Masuda, 1974).

|

Some Stressors on the Social Readjustment Rating Scale (Holmes & Rahe, 1967) |

|

|

Life event |

Life change units |

|

Death of a close family member |

63 |

|

Personal injury or illness |

53 |

|

Dismissal from work |

47 |

|

Change in financial state |

38 |

|

Change to different line of work |

36 |

|

Outstanding personal achievement |

28 |

|

Beginning or ending school |

26 |

|

Change in living conditions |

25 |

|

Change in working hours or conditions |

20 |

|

Change in residence |

20 |

|

Change in schools |

20 |

|

Change in social activities |

18 |

|

Change in sleeping habits |

16 |

|

Change in eating habits |

15 |

|

Minor violation of the law |

11 |

Extensive research has demonstrated that accumulating a high number of life change units within a brief period of time (one or two years) is related to a wide range of physical illnesses (even accidents and athletic injuries) and mental health problems (Monat & Lazarus, 1991; Scully, Tosi, & Banning, 2000). In an early demonstration, researchers obtained LCU scores for U.S. and Norwegian Navy personnel who were about to embark on a six-month voyage. A later examination of medical records revealed positive (but small) correlations between LCU scores prior to the voyage and subsequent illness symptoms during the ensuing six-month journey (Rahe, 1974). In addition, people tend to experience more physical symptoms, such as backache, upset stomach, diarrhea, and acne, on specific days in which self-reported LCU values are considerably higher than normal, such as the day of a family member’s wedding (Holmes & Holmes, 1970).

The Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS) provides researchers a simple, easy-to-administer way of assessing the amount of stress in people’s lives, and it has been used in hundreds of studies (Thoits, 2010). Despite its widespread use, the scale has been subject to criticism. First, many of the items on the SRRS are vague; for example, death of a close friend could involve the death of a long-absent childhood friend that requires little social readjustment (Dohrenwend, 2006). In addition, some have challenged its assumption that undesirable life events are no more stressful than desirable ones (Derogatis & Coons, 1993). However, most of the available evidence suggests that, at least as far as mental health is concerned, undesirable or negative events are more strongly associated with poor outcomes (such as depression) than are desirable, positive events (Hatch & Dohrenwend, 2007). Perhaps the most serious criticism is that the scale does not take into consideration respondents’ appraisals of the life events it contains. As you recall, appraisal of a stressor is a key element in the conceptualization and overall experience of stress. Being fired from work may be devastating to some but a welcome opportunity to obtain a better job for others. The SRRS remains one of the most well-known instruments in the study of stress, and it is a useful tool for identifying potential stress-related health outcomes (Scully et al., 2000).

Go to this site to complete the SRRS scale and determine the total number of LCUs you have experienced over the last year.

Correlational Research

The Holmes and Rahe Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS) uses the correlational research method to identify the connection between stress and health. That is, respondents’ LCU scores are correlated with the number or frequency of self-reported symptoms indicating health problems. These correlations are typically positive—as LCU scores increase, the number of symptoms increase. Consider all the thousands of studies that have used this scale to correlate stress and illness symptoms: If you were to assign an average correlation coefficient to this body of research, what would be your best guess? How strong do you think the correlation coefficient would be? Why can’t the SRRS show a causal relationship between stress and illness? If it were possible to show causation, do you think stress causes illness or illness causes stress?

Hassles

Potential stressors do not always involve major life events. Daily hassles—the minor irritations and annoyances that are part of our everyday lives (e.g., rush hour traffic, lost keys, obnoxious coworkers, inclement weather, arguments with friends or family)—can build on one another and leave us just as stressed as life change events (Figure) (Kanner, Coyne, Schaefer, & Lazarus, 1981).

Daily commutes, whether (a) on the road or (b) via public transportation, can be hassles that contribute to our feelings of everyday stress. (credit a: modification of work by Jeff Turner; credit b: modification of work by “epSos.de”/Flickr)

Daily commutes, whether (a) on the road or (b) via public transportation, can be hassles that contribute to our feelings of everyday stress. (credit a: modification of work by Jeff Turner; credit b: modification of work by “epSos.de”/Flickr)

Researchers have demonstrated that the frequency of daily hassles is actually a better predictor of both physical and psychological health than are life change units. In a well-known study of San Francisco residents, the frequency of daily hassles was found to be more strongly associated with physical health problems than were life change events (DeLongis, Coyne, Dakof, Folkman, & Lazarus, 1982). In addition, daily minor hassles, especially interpersonal conflicts, often lead to negative and distressed mood states (Bolger, DeLongis, Kessler, & Schilling, 1989). Cyber hassles that occur on social media may represent a new source of stress. In one investigation, undergraduates who, over a 10-week period, reported greater Facebook-induced stress (e.g., guilt or discomfort over rejecting friend requests and anger or sadness over being unfriended by another) experienced increased rates of upper respiratory infections, especially if they had larger social networks (Campisi et al., 2012). Clearly, daily hassles can add up and take a toll on us both emotionally and physically.

Other Stressors

Stressors can include situations in which one is frequently exposed to challenging and unpleasant events, such as difficult, demanding, or unsafe working conditions. Although most jobs and occupations can at times be demanding, some are clearly more stressful than others (Figure). For example, most people would likely agree that a firefighter’s work is inherently more stressful than that of a florist. Equally likely, most would agree that jobs containing various unpleasant elements, such as those requiring exposure to loud noise (heavy equipment operator), constant harassment and threats of physical violence (prison guard), perpetual frustration (bus driver in a major city), or those mandating that an employee work alternating day and night shifts (hotel desk clerk), are much more demanding—and thus, more stressful—than those that do not contain such elements. Table lists several occupations and some of the specific stressors associated with those occupations (Sulsky & Smith, 2005).

(a) Police officers and (b) firefighters hold high stress occupations. (credit a: modification of work by Australian Civil-Military Centre; credit b: modification of work by Andrew Magill)

(a) Police officers and (b) firefighters hold high stress occupations. (credit a: modification of work by Australian Civil-Military Centre; credit b: modification of work by Andrew Magill)

|

Occupations and Their Related Stressors

|

|

|

Occupation |

Stressors Specific to Occupation (Sulsky & Smith, 2005) |

|

Police officer |

physical dangers, excessive paperwork, red tape, dealing with court system, coworker and supervisor conflict, lack of support from the public |

|

Firefighter |

uncertainty over whether a serious fire or hazard awaits after an alarm |

|

Social worker |

little positive feedback from jobs or from the public, unsafe work environments, frustration in dealing with bureaucracy, excessive paperwork, sense of personal responsibility for clients, work overload |

|

Teacher |

Excessive paperwork, lack of adequate supplies or facilities, work overload, lack of positive feedback, vandalism, threat of physical violence |

|

Nurse |

Work overload, heavy physical work, patient concerns (dealing with death and medical concerns), interpersonal problems with other medical staff (especially physicians) |

|

Emergency medical worker |

Unpredictable and extreme nature of the job, inexperience |

|

Air traffic controller |

Little control over potential crisis situations and workload, fear of causing an accident, peak traffic situations, general work environment |

|

Clerical and secretarial work |

Little control over job mobility, unsupportive supervisors, work overload, lack of perceived control |

|

Managerial work |

Work overload, conflict and ambiguity in defining the managerial role, difficult work relationships |

Although the specific stressors for these occupations are diverse, they seem to share two common denominators: heavy workload and uncertainty about and lack of control over certain aspects of a job.

Both of these factors contribute to job strain, a work situation that combines excessive job demands and workload with little discretion in decision making or job control (Karasek & Theorell, 1990). Clearly, many occupations other than the ones listed in Table involve at least a moderate amount of job strain in that they often involve heavy workloads and little job control (e.g., inability to decide when to take breaks). Such jobs are often low-status and include those of factory workers, postal clerks, supermarket cashiers, taxi drivers, and short-order cooks. Job strain can have adverse consequences on both physical and mental health; it has been shown to be associated with increased risk of hypertension (Schnall & Landsbergis, 1994), heart attacks (Theorell et al., 1998), recurrence of heart disease after a first heart attack (Aboa-Éboulé et al., 2007), significant weight loss or gain (Kivimäki et al., 2006), and major depressive disorder (Stansfeld, Shipley, Head, & Fuhrer, 2012). A longitudinal study of over 10,000 British civil servants reported that workers under 50 years old who earlier had reported high job strain were 68% more likely to later develop heart disease than were those workers under 50 years old who reported little job strain (Chandola et al., 2008).

Some people who are exposed to chronically stressful work conditions can experience job burnout, which is a general sense of emotional exhaustion and cynicism in relation to one’s job (Maslach & Jackson, 1981). Job burnout occurs frequently among those in human service jobs (e.g., social workers, teachers, therapists, and police officers). Job burnout consists of three dimensions. The first dimension is exhaustion—a sense that one’s emotional resources are drained or that one is at the end of her rope and has nothing more to give at a psychological level. Second, job burnout is characterized by depersonalization: a sense of emotional detachment between the worker and the recipients of his services, often resulting in callous, cynical, or indifferent attitudes toward these individuals. Third, job burnout is characterized by diminished personal accomplishment, which is the tendency to evaluate one’s work negatively by, for example, experiencing dissatisfaction with one’s job-related accomplishments or feeling as though one has categorically failed to influence others’ lives through one’s work.

Job strain appears to be one of the greatest risk factors leading to job burnout, which is most commonly observed in workers who are older (ages 55–64), unmarried, and whose jobs involve manual labor. Heavy alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, being overweight, and having a physical or lifetime mental disorder are also associated with job burnout (Ahola, et al., 2006). In addition, depression often co-occurs with job burnout. One large-scale study of over 3,000 Finnish employees reported that half of the participants with severe job burnout had some form of depressive disorder (Ahola et al., 2005). Job burnout is often precipitated by feelings of having invested considerable energy, effort, and time into one’s work while receiving little in return (e.g., little respect or support from others or low pay) (Tatris, Peeters, Le Blanc, Schreurs, & Schaufeli, 2001).

As an illustration, consider CharlieAnn, a nursing assistant who worked in a nursing home. CharlieAnn worked long hours for little pay in a difficult facility. Her supervisor was domineering, unpleasant, and unsupportive; he was disrespectful of CharlieAnn’s personal time, frequently informing her at the last minute she must work several additional hours after her shift ended or that she must report to work on weekends. CharlieAnn had very little autonomy at her job. She had little say in her day-to-day duties and how to perform them, and she was not permitted to take breaks unless her supervisor explicitly told her that she could. CharlieAnn did not feel as though her hard work was appreciated, either by supervisory staff or by the residents of the home. She was very unhappy over her low pay, and she felt that many of the residents treated her disrespectfully.

After several years, CharlieAnn began to hate her job. She dreaded going to work in the morning, and she gradually developed a callous, hostile attitude toward many of the residents. Eventually, she began to feel as though she could no longer help the nursing home residents. CharlieAnn’s absenteeism from work increased, and one day she decided that she had had enough and quit. She now has a job in sales, vowing never to work in nursing again.

A humorous example illustrating lack of supervisory support can be found in the 1999 comedy Office Space. Follow this link to view a brief excerpt in which a sympathetic character’s insufferable boss makes a last-minute demand that he “go ahead and come in” to the office on both Saturday and Sunday.

Finally, our close relationships with friends and family—particularly the negative aspects of these relationships—can be a potent source of stress. Negative aspects of close relationships can include adverse exchanges and conflicts, lack of emotional support or confiding, and lack of reciprocity. All of these can be overwhelming, threatening to the relationship, and thus stressful. Such stressors can take a toll both emotionally and physically. A longitudinal investigation of over 9,000 British civil servants found that those who at one point had reported the highest levels of negative interactions in their closest relationship were 34% more likely to experience serious heart problems (fatal or nonfatal heart attacks) over a 13–15 year period, compared to those who experienced the lowest levels of negative interaction (De Vogli, Chandola & Marmot, 2007).

Summary

Stressors can be chronic (long term) or acute (short term), and can include traumatic events, significant life changes, daily hassles, and situations in which people are frequently exposed to challenging and unpleasant events. Many potential stressors include events or situations that require us to make changes in our lives, such as a divorce or moving to a new residence. Thomas Holmes and Richard Rahe developed the Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS) to measure stress by assigning a number of life change units to life events that typically require some adjustment, including positive events. Although the SRRS has been criticized on a number of grounds, extensive research has shown that the accumulation of many LCUs is associated with increased risk of illness. Many potential stressors also include daily hassles, which are minor irritations and annoyances that can build up over time. In addition, jobs that are especially demanding, offer little control over one’s working environment, or involve unfavorable working conditions can lead to job strain, thereby setting the stage for job burnout.

Review Questions

According to the Holmes and Rahe scale, which life event requires the greatest amount of readjustment?

- marriage

- personal illness

- divorce

- death of spouse

While waiting to pay for his weekly groceries at the supermarket, Paul had to wait about 20 minutes in a long line at the checkout because only one cashier was on duty. When he was finally ready to pay, his debit card was declined because he did not have enough money left in his checking account. Because he had left his credit cards at home, he had to place the groceries back into the cart and head home to retrieve a credit card. While driving back to his home, traffic was backed up two miles due to an accident. These events that Paul had to endure are best characterized as ________.

- chronic stressors

- acute stressors

- daily hassles

- readjustment occurrences

What is one of the major criticisms of the Social Readjustment Rating Scale?

- It has too few items.

- It was developed using only people from the New England region of the United States.

- It does not take into consideration how a person appraises an event.

- None of the items included are positive.

Which of the following is not a dimension of job burnout?

- depersonalization

- hostility

- exhaustion

- diminished personal accomplishment

Critical Thinking Questions

Review the items on the Social Readjustment Rating Scale. Select one of the items and discuss how it might bring about distress and eustress.

Job burnout tends to be high in people who work in human service jobs. Considering the three dimensions of job burnout, explain how various job aspects unique to being a police officer might lead to job burnout in that line of work.

Personal Application Question

Suppose you want to design a study to examine the relationship between stress and illness, but you cannot use the Social Readjustment Rating Scale. How would you go about measuring stress? How would you measure illness? What would you need to do in order to tell if there is a cause-effect relationship between stress and illness?

Glossary

Daily hassles- Minor irritations and annoyances that are part of our everyday lives and are capable of producing stress

Job burnout- General sense of emotional exhaustion and cynicism in relation to one’s job; consists of three dimensions: exhaustion, depersonalization, and sense of diminished personal accomplishment

Job strain- Work situation involving the combination of excessive job demands and workload with little decision making latitude or job control

Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS) – popular scale designed to measure stress; consists of 43 potentially stressful events, each of which has a numerical value quantifying how much readjustment is associated with the event

14.3 Stress and Illness

In this section, we will discuss stress and illness. As stress researcher Robert Sapolsky (1998) describes, stress-related disease emerges, predominantly, out of the fact that we so often activate a physiological system that has evolved for responding to acute physical emergencies, but we turn it on for months on end, worrying about mortgages, relationships, and promotions. (p. 6)

The stress response, as noted earlier, consists of a coordinated but complex system of physiological reactions that are called upon as needed. These reactions are beneficial at times because they prepare us to deal with potentially dangerous or threatening situations (for example, recall our old friend, the fearsome bear on the trail). However, health is affected when physiological reactions are sustained, as can happen in response to ongoing stress.

Psychophysiological Disorders

If the reactions that compose the stress response are chronic or if they frequently exceed normal ranges, they can lead to cumulative wear and tear on the body, in much the same way that running your air conditioner on full blast all summer will eventually cause wear and tear on it. For example, the high blood pressure that a person under considerable job strain experiences might eventually take a toll on his heart and set the stage for a heart attack or heart failure. Also, someone exposed to high levels of the stress hormone cortisol might become vulnerable to infection or disease because of weakened immune system functioning (McEwen, 1998).

Robert Sapolsky, a noted Stanford University neurobiologist and professor, has for over 30 years conducted extensive research on stress, its impact on our bodies, and how psychological tumult can escalate stress—even in baboons. Here are two videos featuring Dr. Sapolsky: one is regarding killer stress and the other is an excellent in-depth documentary from National Geographic.

Physical disorders or diseases whose symptoms are brought about or worsened by stress and emotional factors are called psychophysiological disorders. The physical symptoms of psychophysiological disorders are real and they can be produced or exacerbated by psychological factors (hence the psycho and physiological in psychophysiological). A list of frequently encountered psychophysiological disorders is provided in Table.

|

Types of Psychophysiological Disorders (adapted from Everly & Lating, 2002) |

|

|

Type of Psychophysiological Disorder |

Examples |

|

Cardiovascular |

hypertension, coronary heart disease |

|

Gastrointestinal |

irritable bowel syndrome |

|

Respiratory |

asthma, allergy |

|

Musculoskeletal |

low back pain, tension headaches |

|

Skin |

acne, eczema, psoriasis |

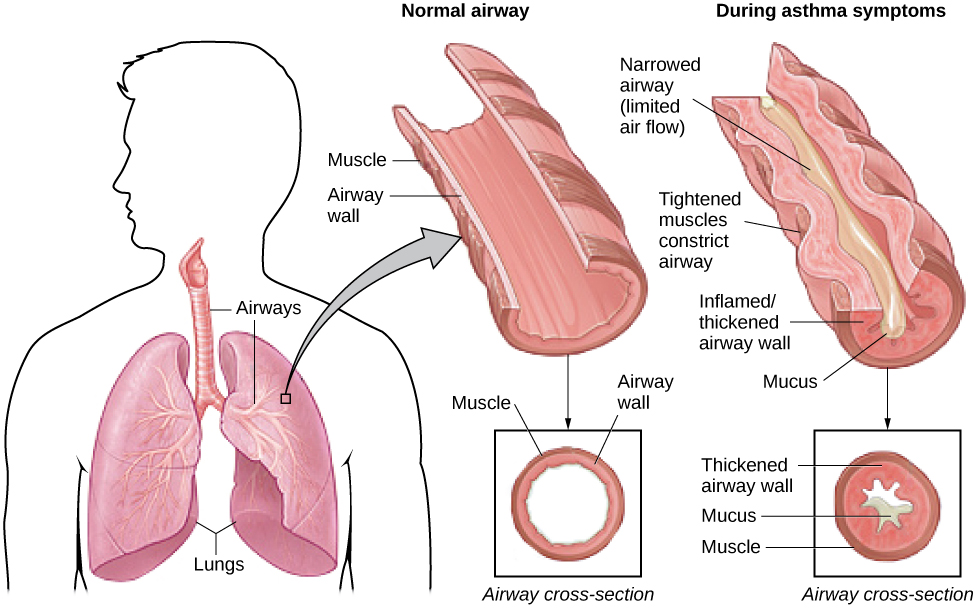

In addition to stress itself, emotional upset and certain stressful personality traits have been proposed as potential contributors to ill health. Franz Alexander (1950), an early-20th-century psychoanalyst and physician, once postulated that various diseases are caused by specific unconscious conflicts. For example, he linked hypertension to repressed anger, asthma to separation anxiety, and ulcers to an unconscious desire to “remain in the dependent infantile situation—to be loved and cared for” (Alexander, 1950, p. 102). Although hypertension does appear to be linked to anger (as you will learn below), Alexander’s assertions have not been supported by research. Years later, Friedman and Booth-Kewley (1987), after statistically reviewing 101 studies examining the link between personality and illness, proposed the existence of disease-prone personality characteristics, including depression, anger/hostility, and anxiety. Indeed, a study of over 61,000 Norwegians identified depression as a risk factor for all major disease-related causes of death (Mykletun et al., 2007). In addition, neuroticism—a personality trait that reflects how anxious, moody, and sad one is—has been identified as a risk factor for chronic health problems and mortality (Ploubidis & Grundy, 2009).

Below, we discuss two kinds of psychophysiological disorders about which a great deal is known: cardiovascular disorders and asthma. First, however, it is necessary to turn our attention to a discussion of the immune system—one of the major pathways through which stress and emotional factors can lead to illness and disease.

Stress and the Immune System

In a sense, the immune system is the body’s surveillance system. It consists of a variety of structures, cells, and mechanisms that serve to protect the body from invading toxins and microorganisms that can harm or damage the body’s tissues and organs. When the immune system is working as it should, it keeps us healthy and disease free by eliminating bacteria, viruses, and other foreign substances that have entered the body (Everly & Lating, 2002).

Immune System Errors

Sometimes, the immune system will function erroneously. For example, sometimes it can go awry by mistaking your body’s own healthy cells for invaders and repeatedly attacking them. When this happens, the person is said to have an autoimmune disease, which can affect almost any part of the body. How an autoimmune disease affects a person depends on what part of the body is targeted. For instance, rheumatoid arthritis, an autoimmune disease that affects the joints, results in joint pain, stiffness, and loss of function. Systemic lupus erythematosus, an autoimmune disease that affects the skin, can result in rashes and swelling of the skin. Grave’s disease, an autoimmune disease that affects the thyroid gland, can result in fatigue, weight gain, and muscle aches (National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases [NIAMS], 2012).

In addition, the immune system may sometimes break down and be unable to do its job. This situation is referred to as immunosuppression, the decreased effectiveness of the immune system. When people experience immunosuppression, they become susceptible to any number of infections, illness, and diseases. For example, acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) is a serious and lethal disease that is caused by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which greatly weakens the immune system by infecting and destroying antibody-producing cells, thus rendering a person vulnerable to any of a number of opportunistic infections (Powell, 1996).

Stressors and Immune Function

The question of whether stress and negative emotional states can influence immune function has captivated researchers for over three decades, and discoveries made over that time have dramatically changed the face of health psychology (Kiecolt-Glaser, 2009). Psychoneuroimmunology is the field that studies how psychological factors such as stress influence the immune system and immune functioning. The term psychoneuroimmunology was first coined in 1981, when it appeared as the title of a book that reviewed available evidence for associations between the brain, endocrine system, and immune system (Zacharie, 2009). To a large extent, this field evolved from the discovery that there is a connection between the central nervous system and the immune system.

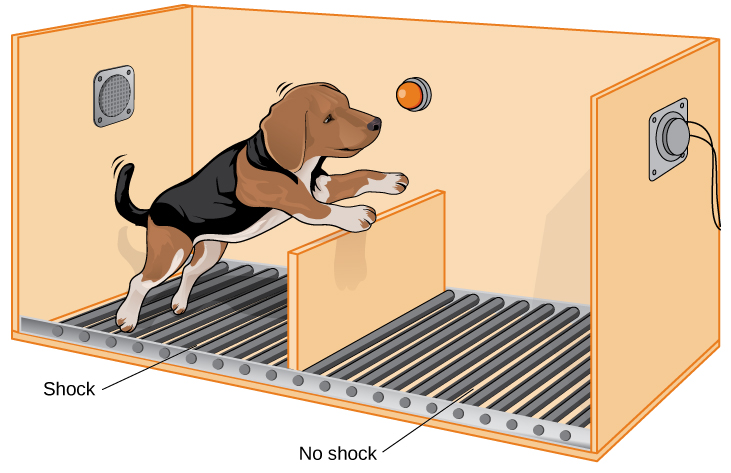

Some of the most compelling evidence for a connection between the brain and the immune system comes from studies in which researchers demonstrated that immune responses in animals could be classically conditioned (Everly & Lating, 2002). For example, Ader and Cohen (1975) paired flavored water (the conditioned stimulus) with the presentation of an immunosuppressive drug (the unconditioned stimulus), causing sickness (an unconditioned response). Not surprisingly, rats exposed to this pairing developed a conditioned aversion to the flavored water. However, the taste of the water itself later produced immunosuppression (a conditioned response), indicating that the immune system itself had been conditioned. Many subsequent studies over the years have further demonstrated that immune responses can be classically conditioned in both animals and humans (Ader & Cohen, 2001). Thus, if classical conditioning can alter immunity, other psychological factors should be capable of altering it as well.

Hundreds of studies involving tens of thousands of participants have tested many kinds of brief and chronic stressors and their effect on the immune system (e.g., public speaking, medical school examinations, unemployment, marital discord, divorce, death of spouse, burnout and job strain, caring for a relative with Alzheimer’s disease, and exposure to the harsh climate of Antarctica). It has been repeatedly demonstrated that many kinds of stressors are associated with poor or weakened immune functioning (Glaser & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2005; Kiecolt-Glaser, McGuire, Robles, & Glaser, 2002; Segerstrom & Miller, 2004).

When evaluating these findings, it is important to remember that there is a tangible physiological connection between the brain and the immune system. For example, the sympathetic nervous system innervates immune organs such as the thymus, bone marrow, spleen, and even lymph nodes (Maier, Watkins, & Fleshner, 1994). Also, we noted earlier that stress hormones released during hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activation can adversely impact immune function. One way they do this is by inhibiting the production of lymphocytes, white blood cells that circulate in the body’s fluids that are important in the immune response (Everly & Lating, 2002).

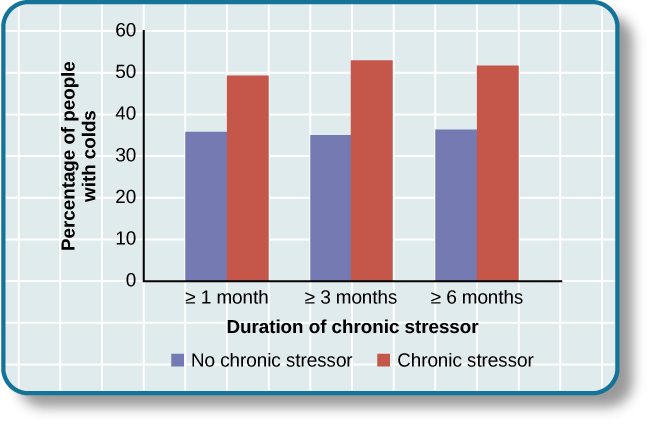

Some of the more dramatic examples demonstrating the link between stress and impaired immune function involve studies in which volunteers were exposed to viruses. The rationale behind this research is that because stress weakens the immune system, people with high stress levels should be more likely to develop an illness compared to those under little stress. In one memorable experiment using this method, researchers interviewed 276 healthy volunteers about recent stressful experiences (Cohen et al., 1998). Following the interview, these participants were given nasal drops containing the cold virus (in case you are wondering why anybody would ever want to participate in a study in which they are subjected to such treatment, the participants were paid $800 for their trouble). When examined later, participants who reported experiencing chronic stressors for more than one month—especially enduring difficulties involving work or relationships—were considerably more likely to have developed colds than were participants who reported no chronic stressors (Figure).

This graph shows the percentages of participants who developed colds (after receiving the cold virus) after reporting having experienced chronic stressors lasting at least one month, three months, and six months (adapted from Cohen et al., 1998).

In another study, older volunteers were given an influenza virus vaccination. Compared to controls, those who were caring for a spouse with Alzheimer’s disease (and thus were under chronic stress) showed poorer antibody response following the vaccination (Kiecolt-Glaser, Glaser, Gravenstein, Malarkey, & Sheridan, 1996).

Other studies have demonstrated that stress slows down wound healing by impairing immune responses important to wound repair (Glaser & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2005). In one study, for example, skin blisters were induced on the forearm. Subjects who reported higher levels of stress produced lower levels of immune proteins necessary for wound healing (Glaser et al., 1999). Stress, then, is not so much the sword that kills the knight, so to speak; rather, it’s the sword that breaks the knight’s shield, and your immune system is that shield.

Stress and Aging: A Tale of Telomeres

Have you ever wondered why people who are stressed often seem to have a haggard look about them? A pioneering study from 2004 suggests that the reason is because stress can actually accelerate the cell biology of aging.

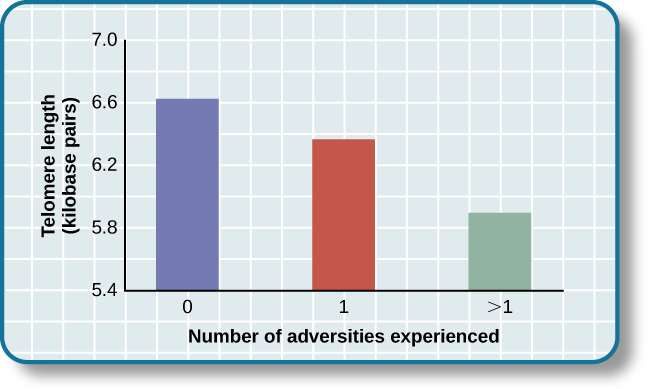

Stress, it seems, can shorten telomeres, which are segments of DNA that protect the ends of chromosomes. Shortened telomeres can inhibit or block cell division, which includes growth and proliferation of new cells, thereby leading to more rapid aging (Sapolsky, 2004). In the study, researchers compared telomere lengths in the white blood cells in mothers of chronically ill children to those of mothers of healthy children (Epel et al., 2004). Mothers of chronically ill children would be expected to experience more stress than would mothers of healthy children. The longer a mother had spent caring for her ill child, the shorter her telomeres (the correlation between years of caregiving and telomere length was r = -.40). In addition, higher levels of perceived stress were negatively correlated with telomere size (r = -.31). These researchers also found that the average telomere length of the most stressed mothers, compared to the least stressed, was similar to what you would find in people who were 9–17 years older than they were on average.

Numerous other studies since have continued to find associations between stress and eroded telomeres (Blackburn & Epel, 2012). Some studies have even demonstrated that stress can begin to erode telomeres in childhood and perhaps even before children are born. For example, childhood exposure to violence (e.g., maternal domestic violence, bullying victimization, and physical maltreatment) was found in one study to accelerate telomere erosion from ages 5 to 10 (Shalev et al., 2013). Another study reported that young adults whose mothers had experienced severe stress during their pregnancy had shorter telomeres than did those whose mothers had stress-free and uneventful pregnancies (Entringer et al., 2011). Further, the corrosive effects of childhood stress on telomeres can extend into young adulthood. In an investigation of over 4,000 U.K. women ages 41–80, adverse experiences during childhood (e.g., physical abuse, being sent away from home, and parent divorce) were associated with shortened telomere length (Surtees et al., 2010), and telomere size decreased as the amount of experienced adversity increased (Figure).

Telomeres are shorter in adults who experienced more trauma as children (adapted from Blackburn & Epel, 2012)..

Telomeres are shorter in adults who experienced more trauma as children (adapted from Blackburn & Epel, 2012)..

Efforts to dissect the precise cellular and physiological mechanisms linking short telomeres to stress and disease are currently underway. For the time being, telomeres provide us with yet another reminder that stress, especially during early life, can be just as harmful to our health as smoking or fast food (Blackburn & Epel, 2012).

Cardiovascular Disorders

The cardiovascular system is composed of the heart and blood circulation system. For many years, disorders that involve the cardiovascular system—known as cardiovascular disorders—have been a major focal point in the study of psychophysiological disorders because of the cardiovascular system’s centrality in the stress response (Everly & Lating, 2002). Heart disease is one such condition. Each year, heart disease causes approximately one in three deaths in the United States, and it is the leading cause of death in the developed world (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2011; Shapiro, 2005).

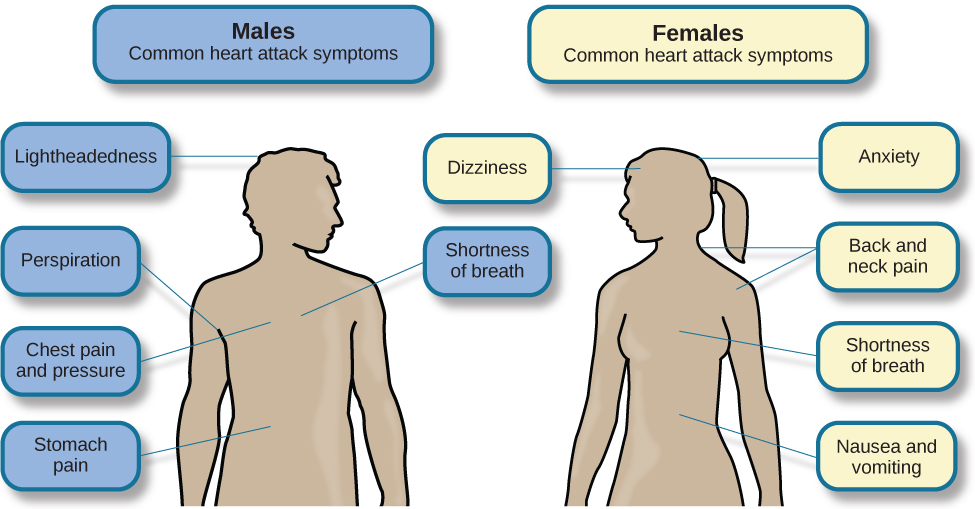

The symptoms of heart disease vary somewhat depending on the specific kind of heart disease one has, but they generally involve angina—chest pains or discomfort that occur when the heart does not receive enough blood (Office on Women’s Health, 2009). The pain often feels like the chest is being pressed or squeezed; burning sensations in the chest and shortness of breath are also commonly reported. Such pain and discomfort can spread to the arms, neck, jaws, stomach (as nausea), and back (American Heart Association [AHA], 2012a) (Figure).

Males and females often experience different symptoms of a heart attack.

A major risk factor for heart disease is hypertension, which is high blood pressure. Hypertension forces a person’s heart to pump harder, thus putting more physical strain on the heart. If left unchecked, hypertension can lead to a heart attack, stroke, or heart failure; it can also lead to kidney failure and blindness. Hypertension is a serious cardiovascular disorder, and it is sometimes called the silent killer because it has no symptoms—one who has high blood pressure may not even be aware of it (AHA, 2012b).

Many risk factors contributing to cardiovascular disorders have been identified. These risk factors include social determinants such as aging, income, education, and employment status, as well as behavioral risk factors that include unhealthy diet, tobacco use, physical inactivity, and excessive alcohol consumption; obesity and diabetes are additional risk factors (World Health Organization [WHO], 2013).

Over the past few decades, there has been much greater recognition and awareness of the importance of stress and other psychological factors in cardiovascular health (Nusair, Al-dadah, & Kumar, 2012). Indeed, exposure to stressors of many kinds has also been linked to cardiovascular problems; in the case of hypertension, some of these stressors include job strain (Trudel, Brisson, & Milot, 2010), natural disasters (Saito, Kim, Maekawa, Ikeda, & Yokoyama, 1997), marital conflict (Nealey-Moore, Smith, Uchino, Hawkins, & Olson-Cerny, 2007), and exposure to high traffic noise levels at one’s home (de Kluizenaar, Gansevoort, Miedema, & de Jong, 2007). Perceived discrimination appears to be associated with hypertension among African Americans (Sims et al., 2012). In addition, laboratory-based stress tasks, such as performing mental arithmetic under time pressure, immersing one’s hand into ice water (known as the cold pressor test), mirror tracing, and public speaking have all been shown to elevate blood pressure (Phillips, 2011).

Are you Type A or Type B?

Sometimes research ideas and theories emerge from seemingly trivial observations. In the 1950s, cardiologist Meyer Friedman was looking over his waiting room furniture, which consisted of upholstered chairs with armrests. Friedman decided to have these chairs reupholstered. When the man doing the reupholstering came to the office to do the work, he commented on how the chairs were worn in a unique manner—the front edges of the cushions were worn down, as were the front tips of the arm rests. It seemed like the cardiology patients were tapping or squeezing the front of the armrests, as well as literally sitting on the edge of their seats (Friedman & Rosenman, 1974). Were cardiology patients somehow different than other types of patients? If so, how?

After researching this matter, Friedman and his colleague, Ray Rosenman, came to understand that people who are prone to heart disease tend to think, feel, and act differently than those who are not. These individuals tend to be intensively driven workaholics who are preoccupied with deadlines and always seem to be in a rush. According to Friedman and Rosenman, these individuals exhibit Type A behavior pattern; those who are more relaxed and laid-back were characterized as Type B (Figure). In a sample of Type As and Type Bs, Friedman and Rosenman were startled to discover that heart disease was over seven times more frequent among the Type As than the Type Bs (Friedman & Rosenman, 1959).

(a) Type A individuals are characterized as intensely driven, (b) while Type B people are characterized as laid-back and relaxed. (credit a: modification of work by Greg Hernandez; credit b: modification of work by Elvert Barnes)

(a) Type A individuals are characterized as intensely driven, (b) while Type B people are characterized as laid-back and relaxed. (credit a: modification of work by Greg Hernandez; credit b: modification of work by Elvert Barnes)

The major components of the Type A pattern include an aggressive and chronic struggle to achieve more and more in less and less time (Friedman & Rosenman, 1974). Specific characteristics of the Type A pattern include an excessive competitive drive, chronic sense of time urgency, impatience, and hostility toward others (particularly those who get in the person’s way).